Case Law Details

ACME Heergarh Powertech Private Limited Vs Central Board of Indirect Taxes And Customs & Anr. (Delhi High Court)

Conclusion: The statutory scheme underlying the Manufacture and Other Operations in Warehouse Regulations, 2019 (MOOWR) could not be construed as seeking to exclude solar power generation in terms of permissions granted under Section 65 of the Customs Act, 1962.

Held: The writ petitions was filed challenging the validity of instructions dated July 9, 2022, issued by the Central Board of Indirect Taxes and Customs in exercise of powers conferred by Section 151A of the Customs Act, 1962. The instructions pertaining to the warehousing of imported capital goods used in the generation of solar power and the asserted inapplicability of the Manufacture and Other Operations in Warehouse (No. 2) Regulations, 2019 were framed in the backdrop of Section 65 of the Customs Act, 1962. Assessee-company had challenged various Show Cause Notices that came to be issued in purported implementation of the Instruction and which call upon them to explain why the license for warehousing as granted in terms of the MOOWR Regulations was not cancelled. Assessee contended that the instruction was contrary to Section 151A. The Instruction compels and commands the Customs authorities to cancel all licenses pertaining to solar generation units, thus impeding the statutory discretion that otherwise stands conferred upon them. Assessee had also assailed the Instruction on the Anvil of the Proviso to Section 151A, with it being urged that the Board stand statutorily injuncted from framing an order, instruction, or direction that would compel an officer of Customs to make a particular assessment or one that may interfere with the discretion that otherwise stands entrusted in it. The customs authorities stood deprived of the right to examine or adjudge the validity of the licenses held by assessee, and the instructions urge them to take emergent steps to cancel all existing licenses. It contended that the instruction was in essence a direction to the customs officials to not only refrain from granting any fresh licenses but to also review existing licenses. Thus depriving assessee of the opportunity to explain why their licenses granted under the MOOWR Regulations were valid. Assessee contended that the act of grant of the MOOWR license was a judicial function performed by an officer of customs. A fortiori, the cancellation of a license would also be liable to be viewed as a judicial act since, prior to the taking of that decision, the officer of customs would be bound to carry out an inquiry and investigation in consonance with the principles of natural justice. The grant of a license under the MOOWR Regulations must be held to be a judicial act. The solar power developers were abusing the MOOWR Regulations by continuing to house the imported capital goods and not clearing them for home consumption, consequently escaping the liability of 12% GST as well as 18% of the import GST in addition to BCD. Department of Revenue to prevent solar power producers from misusing the provisions of the MOOWR Regulations came to issue the impugned instruction on July 9, 2022. It was held that the entire plank of the argument against solar power generation being permissible under Section 65 was based on the inequitable impact that such activity was likely to have on domestic industry and local generators. That, however, could not constitute a legitimate basis for the Court to reconstruct a statutory provision. The respondents essentially bid us to introduce a condition of ineligibility in the garb of statutory interpretation. It would be wholly incorrect for us to recreate or reassemble Section 65 so as to exclude a particular category of activity based upon the experience of its working or its perceived negative impact on domestic industry. While and hypothetically, it might be open for the respondents to adopt appropriate remedial measures if they be of the opinion that solar power generation by virtue of permissions granted under Section 65 was negatively impacting local generators or distorts the “level playing field”, this Court would clearly not be justified in deploying principles of purposive interpretation to correct that projected and asserted anomaly.

FULL TEXT OF THE JUDGMENT/ORDER OF DELHI HIGH COURT

A. PREFACE

1. These batch of writ petitions assail the validity of a Central Board of Indirect Taxes and Customs1 Instruction dated 09 July 2022 [which hereinafter and for the sake of brevity shall be referred to as the “impugned Instruction”] issued in exercise of powers conferred by Section 151A of the Customs Act, 19622 pertaining to the warehousing of imported capital goods used in the generation of solar power and the asserted inapplicability of the Manufacture and other Operations in Warehouse (No.2) Regulations, 20193 framed in the backdrop of Section 65 of the Act.

2. The petitioners also impugn various Show Cause Notices4 which came to be issued in purported implementation of the impugned Instruction and which calls upon them to explain why the license of warehousing as granted in terms of the MOOWR Regulations be not cancelled. In W.P.(C) 10838/2022, besides assailing the impugned Instruction, the petitioner therein has also impugned the validity of the letter dated 19 July 2022 cancelling the warehouse license of the petitioner. In W.P.(C) 12386/2022, the petitioner has impugned the letter dated 23 August 2022 which sought a provisional duty bond as a condition precedent to the provisional release of the imported goods.

3. The impugned Instruction is questioned, with it being contended that the same is contrary to Section 151A of the Act, and more particularly the Proviso appended thereto. The petitioners would contend that the impugned Instruction compels and commands the Customs authorities to cancel all licenses pertaining to solar generation units and thus impeding the statutory discretion which otherwise stands conferred upon them. The petitioners have also assailed the Instruction on the anvil of the Proviso to Section 151A, with it being urged that the Board stands statutorily injuncted from framing an order, instruction or direction which would compel an officer of Customs to make a particular assessment or one which may interfere with the discretion, which otherwise stands entrusted in it. The submission essentially was that the Customs authorities stand deprived of the right to examine or adjudge the validity of the licenses held by the petitioners and the impugned Instruction urging them to take emergent steps to cancel all existing licenses. According to the petitioners, the Instruction is in essence a direction to the Customs officials to not only refrain from granting any fresh licenses but to also review existing licenses and thus depriving the petitioners of the opportunity to explain why their licenses granted under the MOOWR Regulations were valid.

4. On a more fundamental plane, it was asserted that the impugned Instruction proceeds on a wholly incorrect and erroneous understanding of the scheme underlying Sections 61 and 65 of the Act and the MOOWR Regulations themselves, and which enables an importer to bring into India any capital goods which may then be validly housed in licensed warehouses and a manufacturing process or other operations in relation to those goods being undertaken. The petitioners contend that neither the Act nor the MOOWR Regulations can possibly be construed as excluding solar power generation from its ambit and the stand to the contrary as taken by the respondents being wholly untenable.

5. Although the writ petitions were essentially concerned with the validity of the impugned Instruction, Mr. Venkatraman, the learned ASG had submitted that bearing in mind the larger ramifications concerning solar generation by units like those of the petitioners and their resultant impact on the policy initiative of the Union to accord impetus to domestic industry, the ends of justice would warrant this Court ruling upon the scope and ambit of the MOOWR Regulations itself, even if it were to come to the conclusion that the impugned Instruction was invalid or ultra vires Section 151A of the Act. The learned ASG had urged us to holistically examine the scope and ambit of Sections 61 and 65 of the Act as well as the MOOWR Regulations and authoritatively rule on the question whether solar power generation could be said to be an activity envisaged or permissible. Mr. Venkataraman stressed upon the imperative of such a course being adopted in light of multiple challenges which were pending before various Courts and the need for the controversy itself being rendered a quietus.

6. It is in the aforesaid light that counsels for respective sides proceeded to address submissions which were not merely confined to the validity of the impugned Instruction or the consequential SCNs‘ but also extended to the larger question of whether solar power generation could be said to be an operation or activity permissible under Section 65 of the Act.

B. THE FACTUAL BACKDROP

7. For the purposes of evaluating the challenge which stands raised, we deem it apposite to notice the following salient facts as they obtain in the lead petition, being W.P.(C) 10537/2022. The MOOWR Regulations which came to be promulgated on 01 October 2019 principally provided for a duty deferment on the import of capital goods and inputs intended to be used in manufacturing and other operations within a customs bonded warehouse in terms of Section 65 of the Act. Pursuant to the aforesaid Regulations, the petitioner moved two applications on 15 September 2021 for grant of requisite permissions. The applications for grant of licenses for two private bonded warehouses and to undertake manufacturing or other operations in the said warehouses as referable to Sections 58 and 65 of the Act respectively owed its genesis to an Agreement dated 21 August 2019 entered into between the petitioner and the Maharashtra State Electricity Distribution Company Limited5 for sale of 300 Mega Watt6 electricity. A Power Purchase Agreement7 is stated to have been executed between the petitioner and MSEDCL, in terms of which it is obliged to provide electricity to that governmental entity for a period of 25 years. Undisputedly, a failure on the part of the petitioner to commission the project or to falter in its obligations to supply electricity is liable to be construed as an ―Event of Default‖ as per Clause 10.3.1 of the PPA.

8. The MOOWR Regulations, as noticed above, came into effect from 01 October 2019. They define the scope of eligibility and its application to those who have been granted a license for a warehouse under Section 58 of the Act along with permission to undertake manufacturing or other operations in that warehouse in accordance with Section 65 of the Act. A person desirous of obtaining the aforenoted license under the MOOWR Regulations is obliged to move the Principal Commissioner or the Commissioner of Customs in accordance with Regulation 4. Regulation 3 stipulates that those regulations would apply to all units currently operating under Section 65 as well as those which may apply for grant of permission to operate in accordance with Section 65 of the Act. The grant of permission is governed by Regulation 5 and which enables the competent authority of Customs, upon due verification of the application, to accord permission to the applicant to operate in terms of those Regulations. The permission is to subsist until it comes to be cancelled or surrendered in terms of the provisions of the Act and the rules and regulations framed thereunder.

9. Regulations 3 to 6 of the MOOWR Regulations are reproduced hereinbelow:-

“3. Application.—These regulations shall apply to—

(i) the units that operate under Section 65 of the Act, or

(ii) the units applying for permission to operate under Section 65 of the Act,

4. Eligibility for application for operating under these regulations. –

(1) The following persons shall be eligible to apply for operating under these regulations, –

(i) a person who has been granted a license for a warehouse under section 58 of the Act, in accordance with Private Warehouse Licensing Regulations, 2016.

(ii) a person who applies for a license for a warehouse under section 58 of the Act, along with permission for undertaking manufacturing or other operations in the warehouse under section 65 of the Act.

(2) An application for operating under these regulations shall be made to the Principal Commissioner of Customs or the Commissioner of Customs, as the case may be, along with an undertaking to, –

(i) maintain accounts of receipt and removal of goods in digital form in such format as may be specified and furnish the same to the bond officer on monthly basis digitally;

(ii) execute a bond in such format as may be specified; and

(iii) inform the input-output norms, wherever considered necessary for raw materials and the final products and to inform the revised input-output norms in case of change therein.

5. Grant of permission. –

Upon due verification of the application made as per regulation 4, the Principal Commissioner of Customs or Commissioner of Customs, as the case may be, shall grant permission to operate under the provisions of these regulations.

6. Validity of permission. –

Any permission granted under regulation 5 shall remain valid unless it is cancelled or surrendered, or the license issued under section 58 is cancelled or surrendered, in terms of the provisions of the Act or the rules and regulations made thereunder.”

10. In terms of Regulation 13, a licensee is enabled to transfer warehoused goods to another warehouse or to a customs station for export subject to fulfilment of the conditions stipulated therein. Regulation 13 stands framed in the following words:-

“13. Transfer of goods from a warehouse. –

(1) A licensee shall allow transfer of warehoused goods to another warehouse or to a customs station for export, with due intimation to the bond officer on the Form for transfer of goods from a warehouse.

(2) Upon intimation to the bond officer as sub-regulation (1), the licensee shall, –

(i) allow removal of the goods and their loading onto the means of transport;

(ii) affix a one-time-lock to the means of transport;

(iii) endorse the number of the one-time-lock on the Form and retain a copy thereof;

(iv) endorse the number of the one-time-lock on the transport document and retain a copy thereof;

(v) take into record the removal of the goods; and

(vi) cause to be delivered, copies of the retained documents to the bond officer.”

11. The subject of removal of resultant goods for home consumption or for export is regulated by Regulations 14 and 15 respectively and which read as follows:-

“14. Removal of resultant goods for home consumption.-

(1) A licensee may remove the resultant goods from warehouse for home consumption:

Provided that a bill of entry for home consumption has been filed in respect of the warehoused goods contained in so much of the resultant goods and the import duty, interest, fine and penalties payable, if any, in respect of such goods have been paid.

(2) The licensee shall retain a copy of the bill of entry filed and take into record the goods removed.

15. Removal of resultant goods for export. –

(1) A licensee shall remove the resultant goods from the warehouse for export, upon, –

(i) filing a shipping bill or a bill of export, as the case may be; and

(ii) affixing a one-time-lock to the load compartment of the means of transport in which such goods are removed from the warehouse.

(2) The licensee shall take into record the goods removed.‖

12. In terms of Regulation 20, the Board stands empowered to exempt a class of goods from any of the provisions of the Regulations having regard to the nature thereof or the manner of their transportation or storage. The MOOWR Regulations essentially facilitate the housing of imported capital goods or imported raw materials in a duly designated warehouse and for a manufacturing process being undertaken in relation to and with the involvement of those goods till such time as they remain housed therein. This arrangement leads to the deferral of customs duty to the stage where either the resultant final product or the imported capital goods are cleared from the warehouse for home consumption.

13. This procedure of deferral of customs duty on imported capital goods and the policy of those goods being housed in a designated warehouse is founded upon the provisions of Sections 61 and 65 of the Act, which are reproduced hereinbelow:-

“61. Period for which goods may remain warehoused.—

(1) Any warehoused goods may remain in the warehouse in which they are deposited or in any warehouse to which they may be removed,—

(a) in the case of capital goods intended for use in any hundred per cent export oriented undertaking or electronic hardware technology park unit or software technology park unit or any warehouse wherein manufacture or other operations have been permitted under Section 65, till their clearance from the warehouse;

(b) in the case of goods other than capital goods intended for use in any hundred per cent export oriented undertaking or electronic hardware technology park unit or software technology park unit or any warehouse wherein manufacture or other operations have been permitted under Section 65, till their consumption or clearance from the warehouse; and

(c) in the case of any other goods, till the expiry of one year from the date on which the proper officer has made an order under sub-section (1) of Section 60:

Provided that in the case of any goods referred to in this clause, the Principal Commissioner of Customs or Commissioner of Customs may, on sufficient cause being shown, extend the period for which the goods may remain in the warehouse, by not more than one year at a time:

Provided further that where such goods are likely to deteriorate, the period referred to in the first proviso may be reduced by the Principal Commissioner of Customs or Commissioner of Customs to such shorter period as he may deem fit.

(2) Where any warehoused goods specified in clause (c) of subsection (1) remain in a warehouse beyond a period of ninety days from the date on which the proper officer has made an order under sub-section (1) of Section 60, interest shall be payable at such rate as may be fixed by the Central Government under Section 47, on the amount of duty payable at the time of clearance of the goods, for the period from the expiry of the said ninety days till the date of payment of duty on the warehoused goods:

Provided that if the Board considers it necessary so to do, in the public interest, it may,—

(a) by order, and under the circumstances of an exceptional nature, to be specified in such order, waive the whole or any part of the interest payable under this section in respect of any warehoused goods;

(b) by notification in the Official Gazette, specify the class of goods in respect of which no interest shall be charged under this section;

(c) by notification in the Official Gazette, specify the class of goods in respect of which the interest shall be chargeable from the date on which the proper officer has made an order under sub-section (1) of Section 60.

Explanation.—For the purposes of this section,—

(i) “electronic hardware technology park unit” means a unit established under the Electronic Hardware Technology Park Scheme notified by the Government of India;

(ii) “hundred per cent export oriented undertaking” has the same meaning as in clause (ii) of Explanation 2 to sub-section (1) of Section 3 of the Central Excise Act, 1944 (1 of 1944); and

(iii) “software technology park unit” means a unit established under the Software Technology Park Scheme notified by the Government of India.”

xxxx xxxx xxxx

“65. Manufacture and other operations in relation to goods in a warehouse.—(1) With the permission of the Principal Commissioner of Customs or Commissioner of Customs and subject to the provisions of Section 65-A and such conditions as may be prescribed, the owner of any warehoused goods may carry on any manufacturing process or other operations in the warehouse in relation to such goods.

(2) Where in the course of any operations permissible in relation to any warehoused goods under sub-section (1), there is any waste or refuse, the following provisions shall apply—

(a) if the whole or any part of the goods resulting from such operations are exported, import duty shall be remitted on the quantity of the warehoused goods contained in so much of the waste or refuse as has arisen from the operations carried on in relation to the goods exported:

Provided that such waste or refuse is either destroyed or duty is paid on such waste or refuse as if it had been imported into India in that form;

(b) if the whole or any part of the goods resulting from such operations are cleared from the warehouse for home consumption, import duty shall be charged on the quantity of the warehoused goods contained in so much of the waste or refuse as has arisen from the operations carried on in relation to the goods cleared for home consumption.”

14. Before we proceed further and set out the facts in greater detail, we also deem it appropriate to reproduce Section 65A which though existing on the statute book is yet to be enforced. Section 65A of the Act is reproduced hereinbelow:

“65-A. Goods brought for operations in warehouse to have ordinarily paid certain taxes.—(1) Notwithstanding anything to the contrary contained in this Act or the Customs Tariff Act, 1975 (51 of 1975), the following provisions shall, with effect from such date as may be notified by the Central Government, apply to goods in relation to which any manufacturing process or other operations in terms of Section 65 may be carried out, namely—

(A) the dutiable goods, which are deposited in the warehouse shall be goods on which the integrated tax under sub-section (7) and the goods and services tax compensation cess under subsection (9), of Section 3 of the Customs Tariff Act, 1975 (51 of 1975) have been paid, and only for the purpose of the duty payable, other than the said tax and cess paid, such dutiable goods shall be warehoused goods;

(B) the dutiable goods shall be permitted to be removed for the purpose of deposit in the warehouse, where—

(i) in respect of the goods, an entry thereof has been made by presenting electronically on the customs automated system, a bill of entry for home consumption under Section 46 and the goods have been assessed to duty under Section 17 or Section 18, as the case may be, in accordance with clause (a) of subsection (1) of Section 15;

(ii) the integrated tax under sub-section (7) and the goods and services tax compensation cess under sub-section (9), of Section 3 of the Customs Tariff Act, 1975 (51 of 1975) have been paid in accordance with Section 47;

(iii) on removal of the goods from another warehouse in terms of Section 67, a bill of entry for home consumption under clause (a) of Section 68 has been presented and the integrated tax under sub-section (7), and the goods and services tax compensation cess under sub-section (9), of Section 3 of the Customs Tariff Act, 1975 (51 of 1975) have been paid before the goods are so removed from that other warehouse;

(iv) the provisions of Section 59, subject to the following modifications therein, have been complied with, namely—

(a) for the words ―bill of entry for warehousing”, the words ―bill of entry for home consumption” shall be substituted; and

(b) for the words ―amount of the duty assessed”, the words ―amount of duty assessed, but not paid” shall be substituted;

(c) the duty payable in respect of warehoused goods referred to in clause (A), to the extent not paid, is paid before the goods are removed from the warehouse in such manner as may be prescribed.

(2) The provisions of sub-section (1) shall not apply for the purpose of manufacturing process or other operations in terms of Section 65 to dutiable goods which have been deposited in the warehouse or permitted to be removed for deposit in the warehouse prior to the date notified under that sub-section.

(3) The Central Government may, if it considers necessary or expedient, and having regard to such criteria, including but not limited to, the nature or class or categories of goods, or class of importers or exporters, or industry sector, exempt, by notification, such goods in relation to which any manufacturing process or other operations in terms of Section 65 may be carried out, as may be specified in the notification, from the application of this section.”

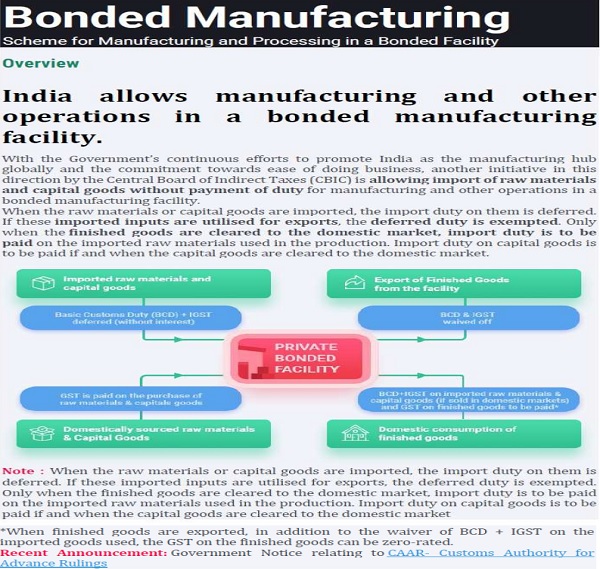

15. As per the petitioners, of equal significance are the Frequently Asked Questions8 issued by the Board seeking to explain the scope and ambit of the MOOWR Regulations. The petitioners in this respect drew our attention to those FAQs‘ and which explains the underlying intent of the MOOWR Regulations to be the facilitation of manufacturing activity being undertaken in a designated warehouse and the importer being enabled to bring into the country capital or non-capital goods without an upfront payment of customs duty and depositing the imported goods in the warehouse either as capital goods or as inputs for further processing.

16. Of significance are the responses framed with respect to questions 8 to 10 of the FAQs‘ which are extracted hereunder:-

“8. Can a unit undertaking manufacture and other operations in a bonded warehouse import capital goods without payment of duty? If yes, whether only BCD or both BCD and IGST on imports is covered? For how long is duty deferment available? Is interest payable after some time?

Response: A unit licensed under Sections 58 and 65 can import capital goods and warehouse them without payment of duty. manufacture and other operations in a bonded warehouse is a duty deferment scheme. Thus both BCD and IGST on imports stand deferred. In the case of capital goods, the import duties (both BCD and IGST) stand deferred till they are cleared from the warehouse for home consumption or are exported. The capital goods can be cleared for home consumption as per Section 68 read with Section 61 of the Customs Act on payment of applicable duty without interest. The capital goods can also be exported after use, without payment of duty as per Section 69 of the Customs Act. The duty deferment is without any time limitation.

9. Would any customs duty be payable on the goods manufactured in the bonded premises using the imported capital goods (on which duty has been deferred) and sold into the domestic tariff area?

Response: The payment of duty on the finished goods is clarified in Para 8 and 9 of the Circular No. 34/2019. Duty on the capital goods would be payable if the capital goods itself are cleared into the domestic market (home consumption). Thus the duty on the capital goods does not get incorporated on the finished goods. Thus no extra duty in finished goods cleared into DTAs payable on account of imported capital goods on which duty has been deferred).

10. Can a unit undertaking manufacture and other operations in a bonded warehouse import inputs without payment of duty? If yes, whether only BCD or both BCD and IGST on imports is covered? For how long is duty deferment available? Is interest payable after some time?

Response: Manufacture and other operations in a bonded warehouse is a duty deferment scheme. Thus both BCD and IGST on imports stand deferred. Thus the case of goods other than capital goods, the import duties (both BCD and IGST) stand deferred till they are cleared from the warehouse for home consumption, and no interest is payable on duty. In case the finished goods are exported, the duty on the imported inputs (both BCD and IGST) stands remitted i.e. they will not be payable. The duty deferment is without any time limitation.

17. As is manifest from the above, the Board explained the benefits of the MOOWR Regulations to be a deferral of both the Basic Customs Duty9 as well as the Integrated Goods and Service Tax10. It was further stated and declared that duty, both BCD and IGST, would stand deferred till such time as the capital goods are cleared from the warehouse for home consumption. This aspect assumes added significance since supply of electricity is exempt from IGST.

18. On 20 and 26 October 2021, licenses came to be granted by the second respondent to the petitioner under the MOOWR Regulations. The terms of the license dated 20 October 2021 are reproduced hereinbelow:-

“GOVERNMENT OF INDIA

MINISTRY OF FINANCE, DEPTT. OF REVENUE

OFFICE OF THE COMMISSIONER OF CUSTOMS,

JODHPUR

Hqrs.: NCR BUILDING, STATUE CIRCLE, C-SCHEME,

JAIPUR-302005

Date: 20.10.2021

GRANT OF LICENSE FOR PRIVATE BONDED WAREHOUSE LICENSE UNDER SECTION 58 OF CUSTOMS ACT, 1962 WITH PERMISSION OF MOOWR UNDER SECTION 65 OF CUSTOMS ACT, 1962 GOVERNED BY THE PRIVATE WAREHOUSE LICENSING REGULATIONS, 2016 NOTIFIED BY NOTIFICATION NO. 71/2016 (N.T.) DATED 14.05.2016 AND 69/2019 DATED 01.10.2019.

LICENSE NO. 08/PBW-ACME HEERGARH Plot-1/Customs Jaipur/2021

This license is hereby granted to M/s Acme Heergarh Powertech Private Limited, having registered address at Plot No. 152, Sector 44, Gurgaon, Haryana-122002 premises at Plot No. 1 located at Khasra No. 102, 102/1, 102/4, 102/5, 102/18, 103/1, 103/2, 103/3, 103/4, 103/5, 103/6, 103/7, 103/8, 103/10, 103/11, 103/12, Village Badisid, Tehsil Bap, Jodhpur-342307 under Section 58 of the Customs Act, 1962 governed by the Private Warehouse Licensing Regulations, 2016 notified by Customs Notification No. 71/2016-Cus (NT) dated 14.05.2016 in respect of private warehouse where dutiable goods imported by or on behalf of the licensee may be deposited along-with permission for undertaking manufacturing or other operations in the warehouse under section 65 of the Act, 1962 governed by the MOOWR Regulation notified by Customs Notification No. 69/2019-Customs dated 01.10.2019.

2. This license is not transferable and will remain in force unless specifically revoked under section 58 of the Customs Act, 1962 or is surrendered in terms of Regulation 8 of Private Warehouse Licensing Regulations, 2016 of the Customs Act, 1962. This license will not affect any right and remedies under the previous license or licenses.

3. The dimensions and measurements of the Private Bonded Warehouse are as follows:

| Warehouse | Measurement |

| Total area available for storage | 4.39 acres |

4. This license is issued under the following conditions:

(i) The license holder shall be held strictly liable for the safe custody of bonded goods and for the strict observance of the provisions of Customs Act, 1962 and/or any other law for the time being in force and the amendments/ Instructions/ orders issued there under from time to time.

(ii) The license holder shall comply with regulations laid down in the Private Warehouse Licensing Regulation, 2016 issued vide notification No. 71/2016- Customs (NT) dated 14.05.2016.

(iii) The license holder shall comply with the regulation laid down in the warehoused goods (Removal) Regulation, 2016 issued vide 67/2016-Customs (NT) dated 14.05.2016.

(iv) The License holder shall comply with the regulations laid down in the Warehouse (Custody and Handling of Goods) Regulation, 2016 issued vide notification No. 68/2016-Customs (NT) dated 14.05.2016.

(v) The license would liable for cease to be valid whenever there is violation/ change of any clause as specified in the undertakings submitted by the licensee unless such change is approved by the competent authority.

(vi) The license holder shall provide annually an all risk insurance policy, that includes natural calamities, riots, fire, theft, skilful pilferage and commercial crime, in favour of the President of India, for a sum equivalent to the amount of duty involved on the dutiable goods proposed to be stored in the warehouse at any point of time. The insurance policy will be liable under the Customs Act, 1962 to compensate this department in the event of any loss or wrong release of the bonded goods.

(vii) The License holder binds himself to pay any duties, interest, fine and penalties arise/payable in respect of warehoused goods.

(viii) The license holder undertakes to indemnify the Pr. Commissioner/ Commissioner of Customs from any liability arising on account of loss suffered in respect of warehoused goods due to accident, damage, deterioration, destruction or any other unnatural cause during their receipt, delivery, storage, dispatch or handling.

(ix) The license holder shall appoint a person who has sufficient experience in warehousing operations and customs procedures as warehouse keeper.

(x) The license would cease to be valid whenever there is change in the constitution of the firm/company unless such change is approved by the competent authority.

(xi) If the license holder intends to cancel the license, they will be inform the proper officer will in advance the date from which they wish to cancel the license.

(xii) The license holder shall provide adequate facilities, equipment and personnel as are sufficient to control access to the warehouse and provide secure storage to the goods in it and also for the examination of goods by the officers of Customs.

(xiii) The packages and their deposition in the warehouse shall be such that every package is easily accessible for inspection. The goods shall be stacked in such a manner as the Assistant/ Deputy Commissioner of Customs may direct.

(xiv) The license holder shall keep record of each activity, operation or actions taken in relation to warehoused goods and produce the same to bond officer as and when required.

(xv) The license holder shall make arrangement for computerized system for accounting of receipt, storage, operation and removal of goods and preserve computerized data of all the records maintained by them for a minimum period of five years.

(xvi) The license holder shall file a monthly return of receipt, storage, operation and removal of goods in the warehouse, within ten days after the close of the month to which such return relates in the prescribed format.

(xvii) The license holder shall preserve updated digital copies of the records at a place other that the warehouse to prevent loss of records due to natural calamities, fire, theft, skill pilferage of computer malfunction as per Warehousing Regulation.

(xviii) The license holder shall regularly pay fees for supervision/services by the official signatory.

(xix) The bonded warehouse shall be visited from time to time by inspector/ and/or Superintendent and/or Assistant/Deputy Commissioner and other officer from the Customs Department. Outdoor travelling expenses shall be borne by the licensee.

5. The Private bonded warehouse will remain under the charge of M/s Acme Heergarh Powertech Private Limited, having registered address at Plot No. 152, Sector 44, Gurgaon, Haryana-122002 premises at Plot No. 1 located at Khasra No. 102, 102/1, 102/4, 102/5. 102/18, 103/1, 103/2, 103/3, 103/4, 103/5, 103/6, 103/7, 103/8, 103/10, 103/11, 103/12, Village Badisid, Tehsil Bap, Jodhpur-342307.

6. The permission is granted to licensee subject to the strict observation of terms and conditions such Instruction/regulations/orders that may be issued time to time.

(Rahul Nangare)

Commissioner

To,

M/s Acme Heergarh Powertech Private Limited (Plot No. 1),

Plot No. 152, Sector 44,

Gurgaon, Haryana-122002‖

19. Pursuant to the aforesaid, the petitioner is also stated to have executed bonds for Plot Nos. 1 and 2 of the licensed warehouses upon deposit of INR 145,07,00,000/- and INR 25,00,000,00 insofar as Plot No.1 is concerned (totalling to INR 170.07 crores) and a corresponding amount of INR 329.93 crores being deposited for Plot No. 2.

20. Thereafter, the impugned Instruction dated 09 July 2022 came to be issued by the Board and which reads as follows:-

“Instruction No.13/2022-Customs

F.No.473/03/2022-LC

Government of India

Ministry of Finance

Department of Revenue

(Central Board of Indirect Taxes & Customs)

*****

Room No 227-A, North Block

New Delhi, July 09, 2022

To,

All Pr. Chief Commissioners/Chief Commissioners, under CBIC

All Pr. Directors General/Directors General, under CBIC

All Pr. Commissioners/Commissioners, under CBIC

Subject: Warehousing of solar power generating units or items like solar panel, solar cell etc. for power plants with resulting goods ‘electricity’ – In-applicability of Manufacture and ‘Other Operations in Warehouse (no.2) Regulations, 2019 under section 65 of the Customs Act, 1962 regarding.

Madam/Sir,

It is brought to notice of the Board that certain solar power generating units applied for permission under section 65 of the Customs Act,1962 for warehousing of imported solar panels/solar modules and related accessories etc. declared as capital goods to generate electricity (from sunlight) as resulting/resultant goods for home consumption. Certain jurisdictional Commissioners have granted such permissions.

2. In this regard, the undersigned is directed to convey that a reading of section 65 shows that in relation to any particular goods, resulting from the operations, they can either be removed from warehouse for export or for home consumption. In respect of applications of the type referred in para 1 above, the resultant electricity is identical whether it be removed for home consumption or for export. In Manufacture and Other Operations in Warehouse (no.2) Regulations, 2019 (hereinafter referred as ‘MOOWR 2019’), the Regulation 15 (removal of resultant goods from the warehouse for export) requires affixing a one-time-lock to the load compartment of the means of transport in which such goods are removed from the warehouse. As the identical goods, e. electricity, may also be cleared for home consumption, the provision for removal for export shows that those goods, i.e. electricity, which are of the nature to which it is incapable to affix one-time-lock to the load compartment of the means of transport in which such goods are removed, fall squarely outside the scope of MOOWR 2019 because of inability to satisfy the essence of the prescribed condition.

3. Moreover, the Regulation 20 is that the Board, having regard to the nature of goods, their manner of transport or storage, may exempt a class of goods from any of the provisions of the MOOWR 2019. Neither this power has been exercised by Board to exempt goods in the nature of electricity from any of the provisions of MOOWR 2019, nor separate regulations relating to removal of electricity have been issued.

4. Incidentally, it may also be noted that the resulting electricity is also not ordinarily capable of being deposited in a warehouse.

5. Accordingly, the undersigned is directed to convey that grant of permission, as referred in para 1 above, is not in accordance with the MOOWR 2019 provisions or principles which are the conditions prescribed by the Board in terms of section 65 of the Customs Act,1962. The permissions granted to the type of generating units referred herein above need to be immediately reviewed and the necessary follow up action taken. No further permissions in such cases should be granted in terms of section 65 of the Customs Act,1962.

(Bullo Mamu)

Under Secretary (LC)‖

21. As is evident from a reading of paragraph 2, the Board took the view that Regulation 15 contemplates the removal of ―resultant goods‖ upon affixation of a one-time-lock on the load compartment of the means of transport in which such goods are removed from the warehouse. The Board opined that since electricity, which may come to be cleared for home consumption, cannot possibly comply with the one-time-lock condition as imposed, it would consequently fall outside the scope of the MOOWR Regulations. As is evident from para 3 of the Instruction, it also took note of the fact that electricity as a class of goods had not been exempted in terms of Regulation 20 and thus reinforcing the applicability of the one-time-lock prescription. The Board also appears to have taken into consideration the fact that electricity is incapable of being deposited in a warehouse. It was in the aforesaid backdrop that the Board held that the grant of any permission under the MOOWR Regulations to solar power generating units which were operating from designated warehouses would not be in accordance with law and therefore the permissions, if any granted, are liable to be immediately reviewed and follow up action be taken.

22. On the basis of the aforenoted Instruction, a SCN dated 13 July 2022 came to be issued against the writ petitioner by the second respondent. The aforesaid SCN was assailed by way of an amendment application which was moved by the petitioner. While considering its application for interim relief, this Court on 13 July 2022 provided that the respondents would stand restrained from taking any coercive measures against the petitioner till the next date of listing. The aforesaid interim order was followed by another order dated 20 July 2022, pursuant to which further proceedings in terms of the impugned SCN were also stayed. The aforesaid interim order dated 20 July 2023 staying the operation of the impugned SCN was confirmed and made absolute during the pendency of the writ petition on 26 August 2022.

C. SUBMISSIONS OF ACME AND AVAADA

23. Appearing for the ACME and AVAADA entities in the instant batch of petitions, Mr. Sujit Ghosh, learned senior counsel, advanced the following submissions. Mr. Ghosh, at the outset contended that the grant of a licence is essentially a judicial act. It was his submission that the grant of a licence is preceded by the officer of Customs conducting an investigation and inquiry in order to verify the particulars set out in an application. Subsequently, after due application of mind, the officer of Customs may grant a licence if it be satisfied that the conditions for grant are fulfilled. According to Mr. Ghosh, it can be discerned from the above that once an application is made, the officer of Customs is required to act in a quasi-judicial manner. It was submitted that where the law requires an authority to make the requisite inquiry before arriving at a decision, it partakes the character of a quasi-judicial function. In support of the aforesaid submission, Mr. Ghosh placed reliance upon the following observations as appearing in Indian National Congress (I) vs. Institute of Social Welfare & Ors11:

“27. What distinguishes an administrative act from a quasi-judicial act is, in the case of quasi-judicial functions under the relevant law the statutory authority is required to act judicially. In other words, where law requires that an authority before arriving at a decision must make an enquiry, such a requirement of law makes the authority a quasi-judicial authority.‖

24. It was then contended that an authority which is vested with the power to determine questions or disputes affecting the rights of citizens is bound to act judicially. According to learned senior counsel, the obligation to act judicially would mean that the decision which is arrived at must conform to an objective standard or criterion laid down or recognized by law. As a necessary corollary, according to Mr. Ghosh, the soundness or otherwise of the determination must be capable of being tested by the same external standard. According to Mr. Ghosh, for an act to be termed as judicial, the following tests as enunciated in Jaswant Sugar Mills Ltd v. Lakshmi Chand & Ors12 must be met:

“13. To make a decision or an act judicial, the following criteria must be satisfied:

“(1) it is in substance a determination upon investigation of a question by the application objective standards to facts found in the light of pre-existing legal rules;

(2) it declares rights or imposes upon parties obligations affecting their civil rights; and

(3) that the investigation is subject to certain procedural attributes contemplating an opportunity of presenting its case to a party, ascertainment of facts by means of evidence if a dispute be on questions of fact, and if the dispute be on question of law on the presentation of legal argument, and a decision resulting in the disposal of the matter on findings based upon those questions of law and fact.”

25. Tested on the aforesaid principles, Mr. Ghosh would contend that the act of grant of the MOOWR license is a judicial function performed by an officer of Customs. A fortiori, the cancellation of a license would also be liable to be viewed as a judicial act since prior to the taking of that decision, the officer of Customs would be bound to carry out an inquiry and investigation in consonance with the principles of natural justice. Mr. Ghosh, in this respect invited our attention to the enunciation of the legal position as appearing in a decision rendered by the Madhya Pradesh High Court in Sukhlal vs Collector, Satna13 and where the following observations were made:

“With this background we now come back to the question raised in this case regarding the nature of the duty imposed on the licensing authority by section 31(1) of the Central Provinces Excise Act in the matter of cancellation or suspension of a licence. We are here essentially concerned with clause (b) of section 31(1) as the petitioner’s licence was cancelled under that clause That provision enables the licensing authority to cancel a licence ―in the event of any breach by the holder there of or by any of his servants, or by anyone acting on his behalf with his express or implied permission of any of the terms or conditions there of.‖ It must be noticed that the charge or breach of terms or conditions of a licence is one which will require investigation before it is found as a fact and if the licensee against whom such a charge is levelled is given an opportunity to meet it, it may be possible for him to disprove the same. Cancellation of a licence is a serious matter as it deprives the licensee of his right to carry on business. In our opinion, the nature of the duty to determine whether the licensee has committed any breach of terms or conditions of his licence and whether for that reason the licence should be cancelled, imposes upon the authority the duty to act judicially. It necessarily follows that the authority must follow the requirements of natural justice and must give an opportunity to the licensee to meet the allegations of breaches of terms and conditions of the licence reported against him before cancelling the licence. As in the instant case, this opportunity was not given to the petitioner, it has to be held that the cancellation of his licence was invalid and void.

Before concluding, we must notice the argument advanced by the learned Government Advocate that the petitioner should not be granted any relief, as he did not avail of the alternative remedy of going up in appeal against the order of the Collector. The existence of an alternative remedy is not always a bar for issuance of writ of certiorari. It is no doubt true that the High Court may refuse to exercise its jurisdiction under Article 226, if the petitioner did not avail of alternative remedies, but the rule requiring the exhaustion of alternative remedies before the writ will be issued is not a rule of law but is a rule of policy, convenience and discretion. The High Court will readily issue a writ of certiorari in a case where there has been a denial of natural justice; State of U.P. v. Mohd. Nooh, [AIR 1958 SC 86]. In the instant case, we have already held that the Collector in cancelling the petitioner’s licence, did not follow the requirements of natural justice. This defect is fundamental and it would not be a sound exercise of discretion to refuse to interfere simply on the ground that the petitioner could have gone up in appeal.

The petition is allowed. The order of the Collector cancelling the petitioner’s licence is quashed. There will be no order as to costs of this petition. The amount of security deposit shall be refunded to the petitioner.‖

26. Without prejudice to the above, Mr. Ghosh submitted that assuming without admitting that the licence granted to the petitioner to operate a solar power plant is a mere permission to operate as a warehouse under Section 65 of the Act, even then such permission is liable to be construed as a judicial action. Mr. Ghosh submitted that the grant of permission contemplated under Section 65 of the Act would be preceded by investigation, ascertainment and verification of facts disclosed by the applicant against objective standards. The submission was that the grant of permission is thus not liable to be understood as being based upon a mere subjective satisfaction of an officer of Customs. Accordingly, Mr. Ghosh contended, the grant of a license under the MOOWR Regulations must be held to be a judicial act. Learned senior counsel submitted that if the aforesaid precepts are borne in mind, it would be manifest that para 5 of the impugned Instruction essentially directs the officer of Customs to review permissions which had been granted and take necessary follow-up action.

27. Emphasis was also laid on the impugned Instruction mandating that no further permissions in respect of solar power projects should be granted under the MOOWR Regulations. Mr. Ghosh contended that the net effect of the above would be that officers of Customs not only stand restrained from granting any future licenses, they are also compelled to review existing licences based on the Instruction which had already concluded that the MOOWR Regulations would be inapplicable to solar power projects. Learned senior counsel underscored the fact that an officer of Customs is bound by the view taken and expressed by the first respondent. This, according to the learned senior counsel would inevitably lead to the cancellation of licenses held by ACME and AVAADA. Mr. Ghosh submitted that the aforesaid apprehension of ACME and AVAADA stands fortified by the issuance of the SCNs‘ in terms of which the Customs authorities propose to cancel the licences held by the said petitioners. Mr. Ghosh further point out that in W.P.(C) 10838/2022, the license held by the petitioner therein has in fact come to be cancelled.

28. Mr. Ghosh submitted that it is trite law that if the power exercised by an authority is quasi-judicial, the same cannot be controlled by directives. It was his submission that no authority, howsoever high it may be placed, can control or dictate the decision-making function of a judicial or a quasi-judicial authority. According to learned senior counsel, any such dictate would clearly impinge upon the obligation of the quasi-judicial authority to act independently and impartially. Reliance in this respect was placed on the following observations as rendered by the Supreme Court in Orient Paper Mills Ltd. vs Union of India14:

“8. If the power exercised by the Collector was a quasi-judicial power — as we hold it to be — that power cannot be controlled by the directions issued by the Board. No authority however high placed can control the decision of a judicial or a quasi-judicial authority. That is the essence of our judicial system. There is no provision in the Act empowering the Board to issue directions to the assessing authorities or the Appellate Authorities in the matter of deciding disputes between the persons who are called upon to pay duty and the department. It is true that the assessing authorities as well as the Appellate Authorities are judges in their own cause; yet when they are called upon to decide disputes arising under the Act they must act independently and impartially. They cannot be said to act independently if their judgment is controlled by the directions given by others. Then it is a misnomer to call their orders as their judgments; they would essentially be the judgments of the authority that gave the directions and which authority had given those judgments without hearing the aggrieved party. The only provision under which the Board can issue directions is Rule 233 of the Rules framed under the Act. That rule says that the Board and the Collectors may issue written Instructions providing for any supplemental matters arising out of these Rules. Under this rule the only Instruction that the Board can issue is that relating to administrative matters; otherwise, that rule will have to be considered as ultra vires Section 35 of the Act.‖

In view of the above, it was submitted that the direction as embodied in the impugned Instruction not to grant further licenses as well as to review existing licences would be in the teeth of the principles laid down in Orient Paper Mills.

29. Reliance was additionally placed on the following passages as appearing in the decision of the Delhi High Court in Faridabad Iron & Steel Traders Association vs. Union of India15.

“92. Now we propose to examine the other main issue involved in the case, whether in the guise of the Circular the respondents have in fact brought out a revenue legislation for imposing excise duty. The other obvious question which arises for adjudication is whether according to the ambit and scope of Section 37B Excise Duty can be imposed? In order to properly comprehend Section 37B of the Act it is necessary to reproduce Section 37-B, which reads as under:

“Instructions to Central Excise Officers. – The Central Board of Excise and Customs constituted under the Central Boards of Revenue Act, 1963 (54 of 1963), may, if it considers it necessary or expedient so to do for the purpose of uniformity in the classification of excisable goods or with respect to levy of duties of excise on such goods, issue such orders, Instructions and directions to the Central Excise Officers as it may deem fit, and such officers and all other persons employed in the execution of this Act shall observe and follow such orders, Instructions and directions of the said Board:

Provided that no such orders, instructions or directions shall be issued—

(a) so as to require any Central Excise Officer to make a particular assessment or to dispose off a particular case in a particular manner; or

(b) so as to interfere with the discretion of the Commissioner of Central Excise (Appeals) in the exercise of his appellate ‖

93. Division Bench of Gujarat High Court in Genset Engineers Pvt. Limited Union of India reported as 1989 (43) E.L.T. 24 (Guj.) held that ―It is clear from Section 37B that the Administrative orders Instructions and directions have to be observed by the excise authorities who are bound by such orders. Nevertheless, the section has taken particular care to see that the authorities who will be acting as quasi judicial authorities are protected from such type of directions or Instructions.

94. In Orient Paper Mills Union of India reported as 1978 (2) E.L.T. (J345) (S.C.) : AIR 1969 SC 48 their Lordships of the Supreme Court has laid down that quasi judicial authorities should not allow their judgment to be influenced by administrative considerations or by the Instructions or directions given by their superior. Therefore, Instructions issued by the Board are not binding upon the adjudicating authority.

95. The impugned Circular was issued by the executive and sent to all Chief Commissioners of Central Excise, all Director General of Central Excise, all Commissioners of Central Excise (Appeals) and all Commissioners of Central Excise. Some of these bodies discharge quasi judicial It is the settled position of law that quasi judicial functions cannot be controlled by executive actions by issuing circulars. It is totally impermissible. According to the spirit of Section 37B circulars or directions can be issued in order to achieve the object of uniformity and to avoid discrimination. Such circulars bind the officers only when they act in their administrative capacity. It must be clearly understood that the Board’s circulars Instructions or directions cannot in any manner interfere with quasi judicial powers of the Assessing Officers. Officials exercising quasi judicial powers must ignore any circular or direction interfering with their quasi judicial functions.

96. Whenever any authority is conferred with the power to determine certain questions in judicial and/or quasi judicial manner, the authority is required to exercise the power conferred upon him as per his own discretion. This is the essence of judicial and quasi judicial function. The authority exercising such powers cannot be influenced by any directions, Instructions or the Circulars that may be issued by any other agency. Consequently, the Circular issued by the respondents cannot be permitted to interfere with the discretion of the judicial and quasi judicial authorities.‖

30. Yet another decision which was cited for our consideration in support of the aforenoted submission was of Varsha Plastics Pvt. Ltd. vs. Union of India16 and where the Supreme Court had observed as under:

“30. The proviso to Section 151-A makes it abundantly clear that the Customs Officer who has to make a particular assessment is not bound by such orders or Instructions or directions of the Board. An assessing authority under the Act being a quasi-judicial authority has to act independently in exercise of his quasi-judicial powers and functions. Section 151-A does not in any manner control or affect the independent exercise of quasi-judicial functions by the assessing authority.

31. By the impugned Standing Order 7493 of 1999 dated 3-121999, the Chief Commissioner of Customs has given detailed guidelines and directions for the determination of valuation of plastic items in the light of international prices contained in the foreign finance journals. The direction issued to the assessing authorities is to apply what is described as the Platt rate which is explained as rates and prices maintained in the internationally reputed finance journal Platt’s Weekly Report. It has also given direction as to how classification of mixed material like floor sweeping should be made.

32. The question now is whether the impugned Standing Order in any manner interferes with the independent quasi-judicial function to be discharged in the assessment of duty by the assessing officer. Whatever be the language employed in the Standing Order which may suggest that the said Instructions are in the nature of a mandate or command, the High Court has read down the impugned Standing Order purely as Instructions or guidelines and not as a mandate or command for being obeyed in each individual case of assessment before them.

33. The High Court further held that the Standing Order is to be taken only as an assistance in exercise of the quasi-judicial power of determining value for the purpose of levying of customs duty. We agree with the view of the High Court. As a matter of fact, it is the case of the Department as well that the impugned Standing Order is not binding; it is just in the nature of guidelines to streamline the functioning of Customs Officers at various field formations.‖

31. The validity of the impugned Instruction was also assailed on the basis of the same impinging upon the right of the statutory authority to bear its own independent and unfettered judgment in exercise of its quasi-judicial powers, and any fetter, if placed on the exercise of those powers being liable to be declared as wholly illegal. In support of the aforesaid proposition, Mr. Ghosh drew our attention to the judgment in Anirudhsinhji Karansinhji Jadeja vs. State of Gujarat17 and to para 11 of the report which is extracted hereinbelow:

“11. The case against the appellants originally was registered on 19-3-1995 under the Arms Act. The DSP did not give any prior approval on his own to record any information about the commission of an offence under TADA. On the contrary, he made a report to the Additional Chief Secretary and asked for permission to proceed under TADA. Why? Was it because he was reluctant to exercise jurisdiction vested in him by the provision of Section 20-A(1)? This is a case of power conferred upon one authority being really exercised by another. If a statutory authority has been vested with jurisdiction, he has to exercise it according to its own discretion. If the discretion is exercised under the direction or in compliance with some higher authority’s Instruction, then it will be a case of failure to exercise discretion altogether. In other words, the discretion vested in the DSP in this case by Section 20-A(1) was not exercised by the DSP at all.”

32. Yet another decision which was cited in this connection was that of Commissioner of Police, Bombay vs. Gordhandas Bhanji18 and where the Supreme Court had observed as under:

“14. The Commissioner’s reply dated 3-12-1947/4-12-1947, was:

“I write to inform you that permission granted to your client was cancelled under the orders of the Government who may be approached….”

15. We are clear that this roundabout language would not have been used if the order of cancellation had been that of the We do not mean to suggest that it would have been improper for him to take into consideration the views and wishes of Government provided he did not surrender his own judgment and provided he made the order, but we hold on the material before us that the order of cancellation came from Government and that the Commissioner acted only as a transmitting agent.

xxxx xxxx xxxx

28. It is clear to us from a perusal of these Rules that the only person vested with authority to grant or refuse a licence for the erection of a building to be used for purposes of public amusement is the Commissioner of Police. It is also clear that under Rule 250 he has been vested with the absolute discretion at any time to cancel or suspend any licence which has been granted under the Rules. But the power to do so is vested in him and not in the State Government and can only be exercised by him at his discretion. No other person or authority can do it.”

33. The Instruction was also assailed on the basis of it being in violation of the Proviso to Section 151A. Section 151A of the Act reads thus:

“151-A. Instructions to officers of customs.—The Board may, if it considers it necessary or expedient so to do for the purpose of uniformity in the classification of goods or with respect to the levy of duty thereon or for the implementation of any other provisions of this Act or of any other law for the time being in force, insofar as they relate to any prohibition, restriction or procedure for import or export of goods, issue such orders, Instructions and directions to officers of customs as it may deem fit and such officers of customs and all other persons employed in the execution of this Act shall observe and follow such orders, Instructions and directions of the Board:

Provided that no such order, Instructions or directions shall be issued—

(a) so as to require any such officer of customs to make a particular assessment or to dispose of a particular case in a particular manner; or

(b) so as to interfere with the discretion of the Principal Commissioner of Customs or Commissioner of Customs (Appeals) in the exercise of his appellate functions.‖

34. As is manifest from a reading of the aforenoted provision, Section 151A enables the Board, if it considers it necessary or expedient so to do, to issue orders, instructions and directions to officers of Customs, if it is necessary or expedient for achieving uniformity in the classification of goods and the levy of duty thereon or for the implementation of any provision of the Act. Any such instruction or directive, when issued by the Board would bind officers of Customs and all other persons employed in the execution of the provisions of the Act, and they consequently being liable to observe and follow the same. The Proviso to Section 151A regulates the extent to which those instructions and directions may operate, with it being provided that those directions cannot be issued so as to require an officer of Customs to make a particular assessment or decide a case in a particular manner or to interfere with the discretion of the Commissioner of Customs (Appeals) when exercising its appellate functions.

35. According to Mr. Ghosh, the Board in terms of the impugned Instruction has taken the firm position that the MOOWR Regulations are inapplicable to generation of electricity by solar power plants. As per Mr. Ghosh, the Instruction not only embodies an unequivocal conclusion already reached by the Board with respect to the applicability of the MOOWR Regulations to solar power plants, it proceeds even further to make a declaration that past permissions and licences granted are liable to be viewed as being invalid. It is in the aforesaid backdrop that Mr. Ghosh submitted that the Instruction effectively directs officers of Customs to review all licences and also deprives them of the discretion otherwise conferred by the statute to examine whether a licence or permission had been validly granted. It was submitted that since it is ex facie evident that the Instruction affects the independent exercise of a quasi-judicial function otherwise conferred on the proper officer of Customs, the same is liable to be quashed bearing in mind the principles enunciated by the Supreme Court in Varsha Plastics.

36. Mr Ghosh also submitted that although Faridabad Iron & Steel Traders Association was concerned with Section 37B of the Central Excise Act, 1944, the same assumes significance bearing in mind the fact that the aforenoted provision is pari materia with Section 151A of the Act. It was the submission of Mr. Ghosh that while the power under Section 151A could have been invoked in order to make a particular provision workable within the scheme of the Act, it cannot be exercised or invoked so as to exclude a class of persons from the application of any provision. It was thus contended that the directive of the first respondent requiring the Customs authorities to review all permissions already granted and not to grant any licenses in the future is ultra vires Section 151A and is liable to be set aside.

37. Without prejudice to the above, and on merits, Mr. Ghosh submitted that the first respondent has clearly erred in coming to the conclusion that solar power projects are outside the purview of the MOOWR Regulations. Mr. Ghosh submitted that a bare perusal of Section 65 of the Act evidences the intention of the Legislature to permit manufacturing operations within a warehouse. Learned senior counsel sought to underline the fact that Section 65 of the Act does not exclude any particular industry from its operation. It was submitted that the MOOWR Regulations were first introduced in 1966 vide a notification dated 30 July 1966. The scheme was thereafter updated and reintroduced in terms of a notification issued on 19 June 2019. Our attention was also drawn to the notification dated 01 October 2019 in terms of which the MOOWR Regulations were reintroduced albeit with certain changes. According to Mr. Ghosh, a bare reading of Section 65 of the Act as well as the relevant provisions contained in the MOOWR Regulations as promulgated from time to time will establish that the Legislature never intended to exclude any class or person or industry from its operation. Our attention was also drawn to the policy position taken by the Union Government insofar as the levy of duty on solar cells and modules is concerned. This was sought to be explained with reference to a chart which is extracted hereinbelow:

| “S.No. | Date/ Period | Particular |

| 1. | Till FY 2019-20 | Import of Solar Modules and Solar Cells was free. |

| 2. | FY 2020-21 | Vide Finance Act 2020, duty on solar modules was introduced for the first time.

The Section 117(b) of the Finance Act read with the Third Schedule amended the Chapter 85 (heading CTH 8541 40 11 and CTH 8541 40 12) and introduced a rate of 20% Basic Customs Duty on the import of Solar Modules and Solar Cells. |

| 3. | FY 2020-21 | Although Basic Customs Duty of 20% was introduced vide Finance Act 2020, the exemption under Notification No. 24/2005 – Cus dated 01.03.2005 (as amended) still operated and exempted basic customs duty on the import of solar cells and solar modules. Entry No. 23 of the said Notification exempted all goods under Chapter Heading CTH 8541, which includes Solar Cells and Solar Modules. |

| 4. | FY 2022-23 | Vide Finance Act 2022, duty on solar modules was increased from 20% to 40% and duty on solar cells was increased from 20% to 25% |

| 5. | 01.02.2022 | Notification No. 15/2022 – Cus dated 01.02.2022 was issued wherein the exemptions granted to solar modules and solar cells under Entry 23 of Notification No. 24/2005 – Cus dated 01.03.2005 was withdrawn (through an amendment) with effect from 01.04.2022. Notification No. 15/2022 – Cus dated 01.02.2022 introduced a specific exclusion in Entry 23 to exclude solar cells and solar modules from the purview of the exemption with effect from 01.04.2022. |

| 6. | 01.04.2022 | With effect from 01.04.2022, the import of solar cells and modules would be leviable to customs duty at 25% and 40% respectively.‖ |

38. It was highlighted that up to Financial Year19 2019-20, the import of solar cells and solar modules was free. Mr. Ghosh submitted that it was by virtue of the Finance Act, 2020 that for the first time a duty came to be imposed on solar modules. In terms of the provisions so introduced, a BCD of 20% came to be imposed on the import of solar modules and solar cells. However, according to Mr. Ghosh, solar cells and modules continued to be exempted from BCD by virtue of Notification No. 24/2005 – Cus dated 01.03.200520. It was pointed out by learned senior counsel that although and in terms of the Finance Act, 2022, the duty on the aforesaid articles came to be increased from 20% to 40% [solar modules] and 20% to 25% [solar cells modules], it was by virtue of Notification No. 15/2022- Cus. dated 01 February 2022 that the exemption granted to solar cells and solar modules by virtue of Entry 23 of the 2005 Notification came to be withdrawn and it was only thereafter that they became subject to the levy of BCD with effect from 01 April 2022. It was submitted that insofar as ACME is concerned, the grant of licence as well as certain imports which it made preceded the levy of BCD which came to be enforced with effect from 01 April 2022. Consequently, and according to Mr. Ghosh, it would be wholly incorrect to allege that the petitioner attempted to circumvent duty by availing the benefit of duty deferment under the MOOWR Scheme. According to Mr. Ghosh, this allegation would clearly not sustain bearing in mind the fact that the goods were imported at a time when they were outside the purview of BCD and consequently the question of circumvention would not arise.

39. Mr. Ghosh then submitted that in the absence of any terminal point having been constructed in relation to capital goods being housed in a warehouse, the stand of the respondents would not sustain. Mr. Ghosh laid stress upon Section 61(1)(a) contemplating imported capital goods being duly housed in a warehouse pursuant to a license for establishment of a private warehouse having been obtained under Section 58 along with the grant of permission for carrying on ―any manufacturing process or other operations” under Section 65 and the duty consequently being deferred till such time as those goods are ultimately cleared from the warehouse.

40. Learned senior counsel also laid emphasis on the distinction which Section 61 itself creates between capital goods [Section 61(1)(a)] and ―any other goods” [Section 61(1)(c)] and submitted that it is only in the case of the latter that Section 61 erects a maximum time frame during which they may be warehoused. It was also contended that insofar as ―any other goods” are concerned, the statute creates a maximum window of one year in explicit terms as is evident from Section 61(1)(c) of the Act. The submission essentially was that in the absence of the statute creating an outer limit for capital goods being retained in a warehouse, it would be wholly incorrect for the respondents to assert that the MOOWR Regulations was being misused by the petitioners.

41. Ghosh then submitted that in the absence of generation of electricity being specifically excluded from Section 65, the stand as taken by the Board is rendered wholly unsustainable. Mr. Ghosh submitted that the statute creates no distinction between tangible or intangible products which may come into being consequent to a process of manufacture or other operations being undertaken in the warehouse. More fundamentally, it was submitted that the MOOWR Regulations do not exclude the subject of manufacture or generation of electricity from its ambit. According to learned senior counsel, in the absence of an explicit and unambiguous statutory exclusion, the impugned Instruction cannot sustain and it ought to be quashed and set aside.

42. In our opinion, this would be an appropriate juncture to record the submissions of Mr. Venkataraman, the learned ASG before we proceed to notice the arguments addressed by Mr. Datar, learned senior counsel appearing for Jakson Power in order to lend lucidity and context to the discussion which ensues.

D. SUBMISSIONS OF THE RESPONDENTS

43. The learned ASG firstly sketched out a brief history of the policy measures adopted by the Union Government in respect of solar energy. Mr. Venkataraman submitted that solar cells are classified under Tariff Entry 8541 42 00 whereas solar modules are placed in Tariff Entry 8541 43 00 of the First Schedule to the Customs Tariff Act, 197521. It was pointed out that prior to 01 April 2022, solar cells and solar modules attracted ―Nil” The learned ASG however drew our attention to Notification No. 01/2018-Customs (SG) dated 30 July 2018 and Notification No. 02/2020-Customs(SG) dated 29 July 2020 and in terms of which a safeguard duty was imposed in terms of Section 8B of the 1975 Act on both solar cells and solar modules. The trajectory and the manner in which the safeguard duty was imposed upon solar cells and solar modules was explained with the aid of the following table:-

| “S. No | Description of Goods | Time Period | Safeguard Duty Rate | Subject Countries |

| 1. | “Solar cells whether or not assembled in modules or panels”

Note: Both solar cells & modules |

30.7.2018 to 29.7.2019 | 25% | Developed Countries + China PR + Malaysia |

| 2. | 30.7.2019 to 29.1.2020 | 20% | ||

| 3. | 30.1.2020 to 29.7.2020 | 15% | ||

| 4. | 3.7.2020 to 29.1.2021 | 14.9% | Developed Countries + China PR + Vietnam +Thailand‖ | |

| 5. | 30.1.2021 to 29.7.2021 | 14.5% |

44. The aforesaid submission is liable to be appreciated bearing in mind the findings which were returned by the Designated Authority (Directorate General of Trade Remedies) and which had proposed the imposition of a safeguard duty in terms of the legislative mandate of Section 8B of the 1975 Act in order to avoid serious injury to domestic industry. The learned ASG pointed out that although BCD on solar cells and modules was ―Nil”, they were subjected to a safeguard duty for the period 30 July 2018 to 29 July 2021.

45. The learned ASG apprised us that the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy22 thereafter issued an Office Memorandum23 dated 15 May 2020 proposing the introduction of a graded duty structure on solar cells and modules in order to promote domestic manufacturing. The aforesaid proposal of the MNRE came to be approved in an inter-ministerial meeting between the representatives of the Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Power, MNRE and the Ministry of Commerce and Industry. Mr. Venkataraman submitted that the decisions ultimately taken by the Union in the course of those deliberations came to be duly publicized by an OM dated 09 March 2021 and thus placing all on due notice of the proposed levy of BCD on solar modules and cells commencing from 01 April 2022 and thus almost a year before the levy was to come into effect. We were apprised by the learned ASG that based on the aforesaid proposal, the Union Budget 2022-23 declared that BCD would be imposed on solar cells and modules at the rates of 25% and 40% respectively with effect from 01 April 2022.

46. Mr. Venkataraman pointed out that post the aforesaid developments, MNRE vide its OM dated 27 July 2022 also apprised the Department of Revenue of certain solar power developers misusing the provisions of the MOOWR Regulations so as to avoid customs duty and Goods and Services Tax24 on import of solar cells and modules. Our attention in this respect was drawn to the aforesaid communication which is extracted hereinbelow for ready reference:-

“F. No. 283/31/2022-GRID SOLAR

Government of India

Ministry of New & Renewable Energy

Grid Solar Power Division

Block No. 14, C.G.O. Complex,

Lodhi Road, New Delhi -110003

Dated: 27th July, 2022

OFFICE MEMORANDUM

Sub: ‘Manufacture and Other Operations in Warehouse (no. 2) Regulations, 2019 (MOOWR Scheme): Applicability to Solar PV Power Projects

1. It has been reported to Ministry of New & Renewable Energy (MNRE) that solar power developers are utilizing the provisions of ‘Manufacture and Other Operations in Warehouse (no. 2) Regulations, 2019’ (MOOWR) to avoid import duty and GST on imported solar equipment, while setting up solar power projects. The electricity thus generated from such projects into Domestic Tariff Area is without duty incidence of any kind, as electricity is not a physical good and is exempt from GST. A detailed note is attached at Annexure-I for consideration of Department of Revenue, Ministry of Finance.

2. A representation dated 25.05.2022 received from India Solar Manufacturers Association (ISMA), addressed to Hon’ble Minister (NRE & Power), on this subject is also enclosed for reference.

3. This issues with the approval of Hon’ble Minister (NRE & Power).

(Ayush Gupta)

Scientist-B

Email: ayush.mnre@gov.in

To: The Secretary, Department of Revenue, Ministry of Finance, North Block, New Delhi.

Copy for internal circulation to: Sr. PPS to Secretary/ Sr. PPS to AS (VK)/ DS(VD)/ Sci-D (SK)