Phantom Precedents and Real Risk: When AI ‘Helps’ Judges — The Buckeye Trust Episode, the HC Writ, and a Global Warning

A. Introduction

In December, 2024, a routine tax appeal turned into a cautionary tale about the limits of generative artificial intelligence in legal process. The Bengaluru bench of the Income‑Tax Appellate Tribunal (ITAT) issued an order in Buckeye Trust v. PCIT (ITA No.1051/Bang/2024) on 30 December 2024 that, on its face, relied upon several reported authorities. Within days it became clear that some of those authorities did not exist. Investigations showed that the order quoted and relied on case law that could not be located in any official reporter — an instance of what the parlance now calls an AI “hallucination.” The tribunal withdrew the order and the matter was administratively reassigned; the taxpayer sought relief before the Karnataka High Court which, after the reassignment, treated the writ as infructuous. This episode is important for three reasons: it highlights concrete types of error that can flow from unverified AI use; it shows how tribunals and courts react to errors that touch procedural fairness; and it connects to a broader set of incidents worldwide in which AI‑tainted work produced real reputational and financial consequences.

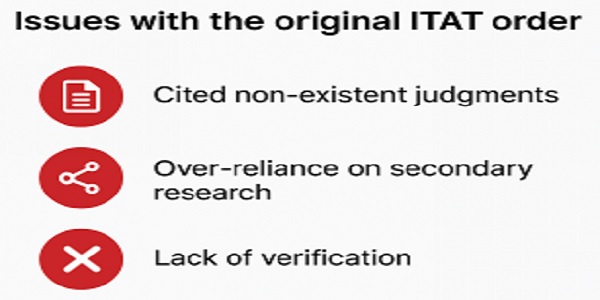

B. Specific Deficiencies Observed in the Withdrawn ITAT Order

A detailed examination of the withdrawn Income Tax Appellate Tribunal (ITAT) order, together with credible professional commentary that followed, reveals several distinct categories of error traceable to unchecked AI-assisted drafting. The errors can be understood under the following heads:

i. Non-existent or fictitious citations

The order referred to a series of judicial precedents — complete with case titles and reporter references — that do not appear in any recognized law journal or online database. On verification, it emerged that the so-called authorities were, in fact, fabricated. This is a classic symptom of “AI hallucination,” where the model confidently generates plausible-looking but entirely spurious legal citations. Such fictitious references can mislead even seasoned professionals if not cross-checked against authentic sources.

ii. Mixed or misattributed authorities

One or more citations cited in the order turned out to be amalgamations of different cases — for instance, combining a party name from one matter with the citation of another. This sort of “blended reference” gives a false impression of legitimacy because it visually resembles a valid citation but actually points to no real judgment. The error typifies an AI system’s tendency to synthesize patterns without understanding legal context, and illustrates why human validation remains indispensable.

iii. Unverified adoption of submissions

Several of the questionable citations appear to have originated from the written submissions of one of the parties — most likely generated using generative-AI tools. The Tribunal appears to have incorporated portions of these submissions directly into its reasoning without verifying the underlying authorities. When a judicial body adopts a party’s AI-generated material without cross-checking, the line between advocacy and adjudication blurs, and the institutional credibility of the order is jeopardized.

iv. Doctrinal overreach built on shaky foundation

Apart from the citation irregularities, the order also advanced an innovative tax-law interpretation — such as equating certain partnership interests to shares for purposes of section 56 of the Income-tax Act. Creative reasoning is not, by itself, objectionable. The problem arises when a novel legal position is supported by authorities that turn out to be fabricated or wrongly cited. A bold doctrinal step, if based on unreliable foundation, becomes doubly fragile and is almost certain to collapse under appellate scrutiny.

v. Breakdown of verification protocols

Finally, the entire episode underscores a systemic failure of basic quality control. Neither the counsel, nor the registry, nor the Bench seems to have undertaken even elementary primary-source checking before issuing the order. Legal citation is not mere ornamentation; it is the evidentiary spine of adjudication. If that spine bends under unverified information, the fairness of the judicial process itself is called into question.

Why these errors matter — fairness, finality, and institutional trust

The fallibility of AI‑generated research affects three core values of adjudication:

(a) Fair hearing: Parties have the right to know the legal authorities a tribunal is using and to test them. If the bench relies on fictive citations, an affected party is denied that meaningful opportunity.

(b) Finality and resource efficiency: A flawed reasoned order consumes scarce judicial and party resources to remedy, whether by recall, rehearing or appellate review.

(c) Institutional legitimacy: Public confidence in courts and tribunals depends on the veracity of what they declare. An order that rests on non‑existent law damages credibility.

C. Administrative and judicial responses: withdrawal, reassignment and writ relief

Following the exposure of fabricated citations in the original ITAT order, the Tribunal promptly withdrew the order and directed a fresh hearing. The taxpayer, however, approached the Karnataka High Court by way of a writ petition [Buckeye Trust (Petitioner) vs. Registrar, ITAT, WP No. 25280 of 2025 (T-IT), judgment dated 18th Sep, 2025] alleging procedural unfairness and apprehension of bias, contending that the same judicial member should not rehear the matter since the earlier order had been “AI-driven.”

Justice M. Nagaprasanna of the Karnataka High Court, taking note of these concerns, issued interim directions restraining the concerned member from participating in the rehearing until the Tribunal’s President could reconstitute the bench. After the reassignment took place, the writ petition was declared infructuous. The High Court thus reinforced an important institutional message: once a tribunal proactively rectifies a procedural defect through internal administrative action, the High Court will generally refrain from further interference, so long as fairness and transparency are restored.

D. The Australian wake‑up call: Deloitte’s refund and what went wrong

The Buckeye episode is not confined to adjudication. Professional services and government consulting are equally vulnerable. In October 2025 the Australian federal government and Deloitte Australia agreed a partial refund after a $439,000 (A$) independent assurance review was found to contain multiple errors, including citations to non‑existent academic papers and a fabricated quote from a federal court judgment. Deloitte later amended the report, disclosed that Azure OpenAI’s GPT‑4o had been used in the drafting, and agreed to repay the final instalment after the client raised concerns. The corrected report left the substantive recommendations intact, but the reputational and contractual consequences were real: a partial refund, heightened parliamentary scrutiny, and likely changes to procurement contracts requiring stricter AI governance. The episode demonstrates how hallucinations can inflict reputational and financial damage beyond the courtroom.

E. U.S. Judicial Sanctions in AI-Assisted Filings — Rewritten Summary (in Original Words)

Since mid-2023, courts across the United States have repeatedly encountered briefs containing non-existent legal authorities created by artificial intelligence tools. The first widely publicized case was Mata v. Avianca, Inc., 678 F. Supp. 3d 443 (S.D.N.Y. 2023), where two attorneys from Levidow, Levidow & Oberman P.C. relied on case law that ChatGPT had fabricated. Judge P. Kevin Castel confirmed that every cited authority was fictitious and imposed a $5,000 sanction, emphasizing that AI can never absolve lawyers from their obligation to verify the accuracy of their submissions. The ruling became a turning point in how courts perceive AI-assisted drafting.

A second significant precedent arose in Park v. Kim, 91 F. 4th 610 (2d Cir. 2024), where the Second Circuit reprimanded counsel for relying on citations generated through AI that could not be traced to any authentic legal source. The court required counsel to submit a corrected memorandum and issued a warning that future reliance on unverifiable AI-assisted citations might invite contempt proceedings. The decision reinforced the principle that human verification remains central to legal responsibility, irrespective of the technology employed.

Following these rulings, other judicial and disciplinary bodies in the United States have reported similar incidents, though some remain unreported in official reporters and are known only through professional media. For instance, Law360 (April 2024) described a New York trial-court case where an advocate’s AI-generated brief contained fabricated citations, prompting the judge to issue a written reprimand and direct attendance at continuing legal-education (CLE) sessions on ethics. Likewise, Reuters Legal (May 2024) reported an Indiana Social Security appeal where the magistrate judge admonished counsel for citing non-existent appellate rulings generated by AI tools, cautioning that “technology cannot replace professional verification.”

In another matter reported by Texas Lawyer (August 2024), the Texas Bar publicly reprimanded an attorney for submitting motions created with AI that contained wholly invented authorities, citing violation of the duty of candour under Rule 3.03. Although these instances were covered by reputable legal media, their underlying judicial or disciplinary orders are not yet formally reported in public law databases such as Westlaw or LexisNexis.

Across these U.S. experiences, a consistent judicial stance is emerging: AI may assist, but not replace, the lawyer’s own diligence. Courts now treat any attempt to pass off unverified AI output as a professional-ethics issue rather than a mere technical error. The resulting sanctions—ranging from fines and compelled corrections to professional reprimands—signal a growing insistence that accountability must remain human-centered, even in an era of automated intelligence.

(Sources: official opinions in Mata v. Avianca, Inc., 678 F. Supp. 3d 443 (S.D.N.Y. 2023) and Park v. Kim, 91 F. 4th 610 (2d Cir. 2024); contextual media reports from Law360 (Apr 2024), Reuters Legal (May 2024), and Texas Lawyer (Aug 2024), none of which are yet reflected in formal case reporters.)

F. Similar episodes worldwide — patterns and precedents

The Indian tribunal and Australian consultancy examples mirror an expanding list of global incidents in which AI‑generated fabrications produced material harm:

- Recurrent institutional corrections. News tracking projects and law‑tech commentators have assembled databases of AI hallucination incidents —from fabricated academic references in expert declarations to misquoted statutes in briefs. The cumulative record is sobering: AI hallucinations keep recurring even after high‑profile sanctions, often because human users treat the tools as authority rather than as drafting assistants. See, for instance, investigative reporting and curated trackers that document dozens of U.S. incidents and numerous international examples.

- Commercial and academic sectors. Beyond courts and consultancies, universities and think tanks have reported instances where AI produced non‑existent literature or mischaracterised study results, resulting in retractions or corrections. The common denominator is the same: a machine‑generated output that looks plausible but lacks verifiable grounding in primary sources.

G. Practical recommendations — immediate and medium‑term safeguards

The Buckeye and Deloitte episodes suggest a practical roadmap:

a. Mandatory verification attestation. Parties, counsel and tribunal secretariats should certify that each cited authority has been checked against a primary source (reporter, law‑site, or court transcript). That attestation can be simple but will create accountability.

b. Disclosure requirement. Any use of generative AI that materially contributes to written submissions or to draft orders should be disclosed, with a summary of the tool used and the extent of its role. Transparency allows courts to calibrate scrutiny and establishes an evidentiary trail.

c. Training and protocols. Judicial chambers, secretariats and law firms must train staff to treat AI outputs as tentative. Protocols should set out required steps for verification (e.g., locating the reporter citation and the headnote or slip opinion).

d. Contractual protections. Government and corporate procurement contracts for consultancy work should require explicit AI‑usage clauses: disclosure, audit rights, and fee adjustments or clawback provisions in the event of material AI‑caused errors.

e. Proportionate sanctions. Bar associations and courts should define proportional sanctions for careless use of AI — fines, mandatory remedial education, or, in egregious cases, disciplinary proceedings. The goal is deterrence balanced with recognition that honest mistakes can occur.

H. Note of Caution: Responsible Use of AI by Judiciary and Tax Professionals

Artificial intelligence has begun to reshape legal and tax research with astonishing speed. Tools that can summarise judgments, draft briefs, or analyse balance sheets now perform

in seconds what once required days of manual effort. Yet, as recent global episodes have demonstrated—from the Mata v. Avianca sanctions in New York to the recall of the AI-assisted ITAT order in Buckeye Trust v. PCIT—the power of automation comes paired with a new category of professional risk.

(i) The Judicial Perspective

For courts and quasi-judicial bodies, AI offers efficiencies in summarising pleadings, organising data, and assisting in precedent retrieval. However, its adoption must be bounded by transparency and human oversight.

-

-

- Authenticity of reasoning: Every order issued in the name of justice must reflect the judge’s own mind. If an AI tool aids in drafting, the final text should be thoroughly reviewed and consciously approved by the human adjudicator.

- Traceability: Any reliance on AI should leave a verifiable trail—metadata, review notes, or human edits—that establish accountability.

- Risk of “AI hallucinations”: Large language models sometimes fabricate facts, citations, or interpretations with convincing fluency. Without human validation, such “hallucinations” can distort both precedent and justice delivery.

-

The Bangalore ITAT episode, where an order was withdrawn because it appeared to be AI-generated without sufficient human oversight, serves as a wake-up call: delegation of judicial reasoning to an algorithm undermines the legitimacy of adjudication itself.

(ii) The Practitioner’s Duty

Tax consultants, chartered accountants, and advocates are already using AI-driven tools to draft submissions, compute liabilities, and analyse statutes. These can be valuable assistants—but never independent authors.

-

-

- Verification is non-negotiable: AI can assist in locating arguments but cannot guarantee their correctness. Every legal citation, section reference, or computational outcome must be cross-checked manually against authentic sources such as the Income-tax Act, CBDT circulars, and judicial databases.

- Confidentiality and data ethics: Uploading client data or case materials into open-source AI systems may expose sensitive information. Professionals must evaluate data-storage terms, confidentiality clauses, and jurisdictional risks before use.

- Misleading outputs: AI tools often sound authoritative even when wrong. Over-reliance can erode analytical judgment, reducing professionals to passive users rather than critical thinkers.

-

(iii) Institutional Responsibilities

Bar councils, tribunals, and professional bodies like ICAI, ICSI, and Bar Associations should proactively:

-

-

- Frame guidelines on AI usagein legal drafting and advisory work.

- Encourage disclosure normswhere AI tools have been used in the preparation of pleadings or orders.

- Conduct training and certificationprograms on responsible AI deployment and digital ethics.

-

The Australian government’s 2025 directive requiring a Big Four audit firm to refund millions in fees due to errors in an AI-generated report illustrates how institutional accountability can extend beyond individuals. In tax administration and audit, such lessons are critical—AI errors may have fiscal consequences as serious as human negligence.

(iv) The Ethical Core

Ultimately, the legal and tax systems rest on human judgment—empathy, reasoning, and fairness cannot yet be mechanised. AI is a tool, not a substitute for intellect or conscience.

Judges, advocates, and tax officers alike must treat AI as an assistant that augments diligence, not an author that replaces it. The safest path is one of “augmented intelligence”, where automation amplifies—but never overrides—professional integrity.

I. Conclusion — a sober recalibration

The lesson is simple but profound: generative AI can dramatically speed up drafting and research, but it cannot replace the human duty to verify. When machines invent precedents or fabricate references and those outputs are accepted without scrutiny, the harm is real — procedurally, financially and reputationally. Buckeye Trust shows how an adjudicative outcome can be destabilized by a string of false authorities; Deloitte’s Australian episode shows that even large consultancies can deliver flawed work when oversight is inadequate. Across jurisdictions, the pattern is now familiar enough that institutions must adapt: by mandating verification, demanding disclosure, training users, inserting contractual safeguards, and, where necessary, imposing sanctions. Doing so preserves the twin pillars of the rule of law and public trust: that what courts and professional advisers declare is demonstrably true, and that mistakes — when they happen — are promptly and transparently corrected.

Note to readers: According to the Economic Times report dated October 29, 2025 (just now),, the Himachal Pradesh High Court has ordered that the deadline for filing returns in audit cases be extended to November 30, 2025, in line with similar directions from the Punjab & Haryana and Gujarat High Courts. The Court passed this order in response to a writ petition filed by local tax professionals, citing technical glitches, delayed release of utilities, and administrative hardship.

This development adds further pressure on the CBDT, which—at the time of reporting—had not yet issued any formal notification under Section 119 of the Income Tax Act, despite multiple High Court orders.

Thanks for sharing article very useful and very informative sir.

Thanks for your nice comment that the article was useful