CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION

SIGNIFICANCE OF THE STUDY

This research holds significant relevance and importance in several key domains:

1. Legal Practice and Policy: In an era where mergers and acquisitions are prevalent, and intellectual property plays a pivotal role in corporate value, this dissertation offers insights and recommendations that can inform legal practitioners, policymakers, and legislators in shaping M&A agreements and IP protection laws.

2. Business Strategy: Businesses engaged in M&A transactions must navigate complex terrain, balancing the need for growth with the preservation of intellectual property value. The research conducted in this dissertation provides practical guidance on how businesses can draft, negotiate, and implement anti-dilution clauses to protect investors’ interests effectively. These insights can lead to more informed strategic decisions.

3. Legal Scholarship: As an academic endeavor, this dissertation contributes to legal scholarship by deepening the understanding of anti-dilution clauses within common law jurisdictions.

4. Equitable Outcomes: Perhaps most importantly, this research addresses the fundamental concept of equity in mergers and acquisitions. It ensures that the interests of IP owners and shareholders are fairly balanced, contributing to more equitable and just outcomes in corporate transactions. This significance resonates with both the legal community and the broader business world.

In conclusion, the dissertation’s significance extends beyond the realm of academia, touching upon practical legal practice, business strategy, and intellectual property management. It seeks to strike a balance between protecting intellectual property assets and promoting equitable corporate transactions within common law jurisdictions, making it a valuable and relevant contribution to the legal and business landscape.

OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY

1. To dissect the structure and components of anti-dilution clauses in M&A agreements: This objective involves a comprehensive analysis of the specific provisions and mechanisms commonly included in anti-dilution clauses within the context of mergers and acquisitions.

2. To assess the legal precedents and court decisions shaping the interpretation of anti-dilution clauses in M&A: This objective aims to examine how common law courts have interpreted and applied anti-dilution clauses in merger and acquisition-related disputes, highlighting the key legal principles and trends that have emerged.

3. To analyze the strategic role of anti-dilution clauses in negotiation and decision-making processes: This objective seeks to explore how anti-dilution clauses influence the valuation, negotiation, and strategic decisions made by companies involved in mergers and acquisitions, and how they affect the overall success of these transactions.

4. To provide recommendations for optimizing the use of anti-dilution clauses in M&A transactions: This objective aims to offer practical guidance to businesses, legal practitioners, and policymakers on best practices for drafting, negotiating, and implementing anti-dilution clauses to ensure the protection of intellectual property rights and the fair treatment of stakeholders in common law jurisdictions.

These research objectives will guide your investigation into the anatomy and jurisprudence of anti-dilution clauses in mergers and acquisitions within common law jurisdictions.

HYPOTHESIS

The effective utilization and interpretation of anti-dilution clauses in mergers within common law jurisdictions contribute to the preservation of the value and integrity of shareholders and investors, resulting in more equitable outcomes for investors and shareholders.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

1. What is the structure and functionality of anti-dilution adjustment clauses within merger agreements in common law jurisdictions, and how do they affect the valuation and distribution of equity or assets in a merger?

2. How do common law jurisdictions differ in their legal treatment and interpretation of anti-dilution adjustment clauses, and what legal precedents exist regarding their application in merger transactions?

3. What are the factors and criteria that trigger the activation of anti-dilution adjustment clauses in mergers, and how do they vary across different types of mergers and industries?

4. To what extent do anti-dilution adjustment clauses influence the negotiation dynamics between merging entities and their stakeholders, and how do they impact the overall success and fairness of merger transactions?

5. What are the challenges and complexities involved in enforcing anti-dilution adjustment clauses in mergers, and how have legal practitioners and courts addressed disputes related to these clauses?

6. How can businesses and legal professionals optimize the drafting and implementation of anti-dilution adjustment clauses in merger agreements to achieve their intended goals and ensure equitable treatment of all parties involved?

These research questions will help you investigate the anatomy and jurisprudence of anti-dilution adjustment clauses in the specific context of mergers within common law jurisdictions.

RESEARCH PROBLEM

The research problem addressed in this research revolves around the critical need to comprehensively understand, analyze, and evaluate the role and efficacy of anti-dilution clauses within the complex and evolving landscape of mergers and acquisitions (M&A). Specifically, it focuses on addressing the following key issues and questions:

1. Structural Variations: What are the structural components and variations of anti-dilution clauses commonly employed in M&A agreements, and how do these components impact the negotiation, valuation, and distribution of assets during mergers?

2. Jurisprudential Insights: How have courts interpreted and applied anti-dilution clauses in the context of mergers, and what legal precedents and principles have emerged from relevant cases? What insights can be drawn from jurisprudence to guide the use and interpretation of these clauses?

3. Practical Implications: What are the practical implications of anti-dilution clauses on the decision-making processes, strategic considerations, and outcomes of M&A transactions? How do these clauses influence the dynamics of mergers, and how do they affect the stakeholders involved?

4. Optimization and Best Practices: What recommendations and best practices can be formulated for the effective utilization of anti-dilution clauses in M&A transactions?

This research problem is of paramount importance as it addresses the intersection of legal, financial, and strategic aspects of M&A transactions, highlighting the crucial role of anti-dilution clauses in protecting the interests of both intellectual property owners and shareholders. By investigating these critical issues, the dissertation seeks to provide a comprehensive understanding of anti-dilution clauses in mergers and contribute valuable insights to enhance their utilization and effectiveness in contemporary corporate transactions.

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

1. Authors: Revathy Muralidharan, Aakash Dasgupta and Aditi Rani

The authors have explored the legal aspects of anti-dilution rights in India, emphasizing that Indian law does not explicitly regulate these provisions, allowing parties to negotiate them freely within the bounds of contract law. Courts in India generally uphold the sanctity of contracts while considering disputes related to anti-dilution provisions.

Additionally, the article touches on the potential challenges associated with anti-dilution rights, such as potential disputes over valuation and the impact on the company’s future funding prospects. It concludes by highlighting the importance of clear and well-drafted provisions to avoid misunderstandings and conflicts1.

2. Authors: Atikant Kaur, Aishwarya H., Parag Srivastava, Pratibha Jain

The writers of this article have come to the conclusion that in order to put this protection into effect, despite the fact that the provision may be easier to negotiate than to carry out, there may be certain legal and regulatory hurdles that need to be cleared. A foreign investor who wishes to exercise their right against dilution has to be aware of the price requirements that have been established under the Foreign Exchange Management (Non-debt Instruments) Rules, 2019, in order to do so. The price at which shares of a private or unlisted Indian business are issued to a non-resident must not be less than the fair market value of those shares, as assessed by any globally known pricing methodology and properly certified by a chartered accountant, merchant banker, or barrister and solicitor. These guidelines specify that the price at which shares of a private or unlisted Indian company are offered to a non-resident must not be less than the fair market value of those. In light of this, it would be challenging to issue shares to a non-resident “free of cost” or at any price that is lower than their current fair market value while still preserving the anti-dilution precaution2.

3. Author: Stephen Choi

Contribution: Stephen Choi’s research covers various aspects of corporate law, including securities regulation and corporate governance. His contributions to the topic of anti-dilution clauses revolve around the legal and economic implications of these provisions. Choi’s analyses often examine the impact of anti-dilution clauses on valuation, financing strategies, and the broader corporate landscape3.

4. Authors: Paul Albert and Ashwin Bhat

The authors contemplate that considering the nuances associated with the issuance of shares at a price below fair market value or for no consideration, the actual implementation of anti-dilution provisions poses a lot of difficulties. Unless certain exceptions are brought in the existing laws, actual implementation could be a challenge in India, especially with respect to foreign investors.

In conclusion, these authors have significantly contributed to the understanding of The Anatomy and Jurisprudence of an Anti-Dilution Clause in Common Law Jurisdictions. Their research and insights provide a comprehensive view of the historical evolution, legal interpretations, contractual considerations, and implications of anti-dilution clauses within the context of corporate finance and securities regulation4.

SCOPE AND LIMITATION OF THE STUDY

Scope:

The scope of this research encompasses a comprehensive examination of the structural components, legal precedents, practical implications, and recommendations related to anti-dilution clauses within the context of mergers and acquisitions (M&A) in common law jurisdictions. The dissertation intends to cover the following areas:

1. Structural Analysis: Investigate the composition and variations of anti-dilution clauses commonly employed in M&A agreements.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

The research methodology employed for this research encompasses a multifaceted approach aimed at gaining a comprehensive understanding of anti-dilution clauses within the context of mergers and acquisitions (M&A) in common law jurisdictions. The research process involves several key components:

1. Literature Review:

- Extensive Review: A thorough review of relevant literature, including academic papers, legal texts, case law, and industry reports, to establish a foundational understanding of anti-dilution clauses, M&A transactions, and IP protection.

2. Legal Analysis:

- Statutory Analysis: Examination of relevant statutes, regulations, and legal frameworks within common law jurisdictions that pertain to M&A and intellectual property rights.

- Case Law Analysis: In-depth analysis of legal precedents and court decisions involving anti-dilution clauses to gain insights into their interpretation and application.

3. Content Analysis:

- M&A Agreements: Analyzing actual M&A agreements that contain anti-dilution clauses (where available and accessible) to dissect their structural components and variations.

4. Comparative Analysis:

- Comparing practices and legal frameworks across multiple common law jurisdictions to identify variations and commonalities in the use and interpretation of anti-dilution clauses.

5. Case Studies:

- Examining select case studies of M&A transactions that prominently feature anti-dilution clauses, with a focus on the practical implications and legal outcomes.

CHAPTER II: THE ANATOMY OF ANTI-DILUTION CLAUSES

The world of mergers and acquisitions (M&A) is a dynamic and complex arena where corporations strategize to achieve growth, efficiency, and competitive advantage. It is a realm where companies merge, acquire, or divest assets, reshaping industries and markets. Within this landscape, value for the investors hold a position of paramount importance. This is the lifeblood of innovation, brand identity, and the foundation upon which competitive advantage is built.

The dilution or erosion of the value and integrity of the assets during mergers can have profound implications, affecting not only the financial well-being of the entities involved but also the future prospects of their finances. Recognizing the significance of this challenge, common law jurisdictions have increasingly turned to anti-dilution clauses as instruments for safeguarding the sanctity and vitality of intellectual property in the midst of corporate transformations.

The anatomy and jurisprudence of anti-dilution clauses in the context of mergers within common law jurisdictions form the central focus of this dissertation. These clauses, once relegated to the periphery of contractual agreements, have emerged as pivotal tools for investors’ protection in M&A transactions. They are essential mechanisms for ensuring that the value of assets remains intact and that the parties involved are equitably treated.

The primary objective of this research is to dissect, scrutinize, and illuminate the intricacies surrounding anti-dilution clauses in the context of mergers in common law jurisdictions. It embarks on a journey that will navigate through the structural elements of these clauses, explore the legal precedents established through jurisprudence, and ultimately provide practical recommendations for their effective utilization in the dynamic world of M&A.

This research is not merely an exercise in theoretical analysis; rather, it is a pragmatic exploration of a topic with profound implications for businesses, legal practitioners, and policymakers alike. It seeks to contribute to the understanding of anti-dilution clauses, their role, and their potential as tools to protect and preserve the value of intellectual property in the complex and transformative environment of mergers in common law jurisdictions.

Investors have provided funding for both individual and group ventures over the course of our history. However, it is widely acknowledged that the modern concept of venture capital began in 1946 with the founding of the American Research and Development Corporation (ARDC) after World War II. This occurred immediately after the conclusion of the war. Since the inception of ARDC, the United States has maintained its position as the dominant player in the international market for venture capital. The American Research and Development Corporation was the very first investing group to go public5. In today’s economy, investments in venture capital are inextricably tied to high rates of job creation and the diffusion of technical advancements. As a direct consequence of this, the majority of industrialized countries have placed a greater emphasis on the promotion of venture capital. Private equity and venture capital may be thought of as a kind of risk capital that is created by businesses, public and private pension funds, endowments, foundations, banks, insurance companies, and wealthy families and people. This is the easiest approach to categorize private equity and venture capital. In general, venture capitalists provide funding for new business endeavors, relatively small businesses that are not publicly traded but have considerable development potential, as well as the acquisition of convertible assets6. Generally speaking, an investment structure is made up of rights and protections that are designed to optimize the return on investment and give liquidity to the venture capitalist. The worth of the firm, the specific exit rights of the investors, and the terms that protect their ownership percentage are some of the most essential aspects included in the investment agreements7. The venture capital industry has been growing steadily since its start, and in the 1990s, there was almost no limit to the amount of money that could be invested. The negotiations were heated, and investors chased after the start-ups that showed the greatest promise. When it comes to the fundamental terms of an investment, business owners sometimes had more negotiation leverage than investors did. The bulk of these investments were made at significantly inflated prices, which led to the venture capital industry supporting thousands of more businesses than it was really capable of supporting.

It is common practice for venture investors to negotiate safeguards against unfavorable outcomes, such as anti-dilution and liquidation advantages, with less focus placed on the goal of maximize their potential upside. Following the bursting of this bubble in the later half of the year 2000, there was a substantial adjustment made to the laws that govern the venture capital industry8. As a consequence of the economic crisis and the falling value of the stock market, tough times were experienced by both the companies and the venture capitalists. Raising funds in this context has proved to be extremely difficult due to the restricted choices available to investors for withdrawing their money as a result of the collapse of the market. Investors are taking a very critical look at business transactions, and the values of companies have fallen dramatically. In order for businesses to get the required funds, they often have to part with a greater portion of their ownership, and subsequent financing is becoming more expensive than the original investment. Anti-dilution protection and liquidation benefits have become the most hotly debated provisions in today’s contemporary corporate environment, at least in the context of the United States. This is due to the fact that down rounds are more common and investors have more negotiation power over the terms of the investment. As a result of investors’ desire to lower their risks and get the greatest downside protection that is now accessible, clauses that were formerly only used in very hazardous or desperate attempts at financing have become increasingly widespread. If these restrictions are put into effect, it is possible that the company and, more specifically, the business owners may suffer significant losses9. Before coming to an agreement on these parameters, it is essential for all parties involved to have a comprehensive understanding of not just the ramifications of anti-dilution protection but also the viable alternatives.

Anti-dilution provisions are often included in deals involving venture capital or private equity in today’s world. This thesis is to describe, assess, and investigate the logic behind the protective mechanism’s purpose as well as the conditions under which anti-dilution protection need to be included in an investment agreement. Additionally, the goal of this thesis is to investigate the circumstances under which anti-dilution protection ought to be included in an investment agreement. Several anti-dilution provision strategies will be assessed, and the real-world impacts of putting each model into action on the relevant parties will be investigated and debated. The positives and negatives of anti-dilution protection, as well as significant considerations that the parties need to take into account before agreeing to anti-dilution measures, will be scrutinized in great detail throughout this phase of the process.

The term venture capital may be interchanged with the term private equity in various contexts. Nevertheless, there is not a description of these ideas that is accepted by the vast majority of people, and the similarities and distinctions between them are not evident. In spite of the fact that both concepts are often used interchangeably, there are instances when it is necessary to differentiate between the two. This is due to the fact that private equity investors just provide financial help to the company, whilst venture capital refers to investments that include an actual ownership stake. It is common practice, at least in Europe, to consider venture capital to be a component of the private equity market as a whole. This is due to the fact that venture capital encompasses earlier stage investments such as seed capital and start-up money. On the other hand, since the purpose of this essay is not to investigate the differences between these two concepts, we shall use these terms interchangeably throughout the whole piece. Now, two concepts are explained for the better understanding of the research piece thereof:

- Anti-dilution adjustment clause

The term “anti-dilution” is seen in many of the investment agreements that are drawn up. Anti-dilution clauses may be included in mergers and acquisitions agreements as well as security contracts. Because of the anti-dilution clause, present investors will be able to keep the same percentage of ownership in the company even if additional securities are issued in the future. This will be accomplished by purchasing an equal number of new shares. Existing shareholders run the danger of seeing both the value of their stockholdings and the ownership percentage of the company they already possess if the securities or merger agreement does not include any anti-dilution adjustment language. This term is essential for businesses that are just getting started or are in their early stages.

- Anti-dilution adjustment clause Anti-Dilution Protection

Before we can fully grasp the concept of anti-dilution protection, we need to have a solid foundational understanding of the concept of dilution. Dilution is the word that is used to describe the decrease in the proportion of a firm that is owned by its shareholders that is caused by fresh shares being bought in subsequent rounds of fundraising. On the other hand, we may say that a fall in the percentage of shares owned by shareholders would occur when a corporation has a higher number of outstanding shares. A protection against dilution may look something like this: Let’s say that A holds 250 of the 1,000 shares of XYZ Corporation that are currently in circulation. In other words, the investor is a shareholder in the corporation to the extent of 25 percent. When it comes time to seek funds for the second round of investment, the XYZ company does so by issuing an extra thousand shares, which are then subscribed for by new investors.

At this time, there remain 2,000 shares that have not been redeemed, which brings A’s holding down to 12.5%. The value of the existing shares will surely decrease if new shares are made available at a price that is much lower than the initial investment made by the present investor. There are times when a firm’s performance is not up to standard, and in certain instances, the corporation may choose to issue shares at a discounted price. The purpose of anti-dilution protection clauses is to safeguard the interests of present shareholders by allowing them to keep their stake in a company at the same level of ownership up to a certain maximum. The anti-dilution protection clause is effectively provided to existing shareholders when the company issues new shares as the result of subsequent fundraising rounds at a rate that is lower than the price paid by present investors. This occurs when the business issues new shares as a result of successive fundraising rounds.

TYPES OF ANTI–DILUTION PROTECTION

In India there are two types of anti-dilution protection which is available for investors:

- Price based anti-dilution provision

> Full ratchet

> Broad-based weighted average

- Contractual anti-dilution adjustment

The explanation, for clear understanding, of both the types is as follows:

PRICE BASED ANTI–DILUTION PROVISION

This is a form of anti-dilution strategy in which public subscription is supplied by issuing new shares, which may reduce the value of shares that are already owned by shareholders who are already present in the company. In succeeding rounds, the price-based anti-dilution clause protects existing shareholders against the company’s practice of issuing shares at prices that are lower than their current value. If investors are provided with a price-based anti-dilution clause, the charter of a firm will include a conversion formula that will allow preferred stock to be converted into common stock. There are two different ways that the price-based anti-dilution clause might be implemented.

- Full ratchet clause

People are able to sign up for this form of anti-dilution in order to get additional shares, which has the potential to diminish the value of the shares that are currently held by owners. The price-based anti-dilution provision shields the present owners against the possibility of receiving shares from the firm that are worth less when each new round of funding is completed. The process of converting preferred stock to common stock is outlined in the charter of a business and must be followed if purchasers are subject to a price-based anti-dilution provision. There are two different scenarios in which the price-based anti-dilution provision might come into play.4. Complete clause followed by a punchline

While the present shareholder benefits from the full ratchet rule, the corporation struggles to comply with the requirements of the regulation. According to the National Venture Capital Association, the price at which new shares are issued would be the new exchange price after the transaction is complete. According to this proposal, in the event that the price of the shares is lower than the amount that current shareholders paid for them during the subsequent round of financing, the price of the existing shareholders’ shares would be outstanding shares, the current price of the share is added to the total number of outstanding shares to arrive at the weighted average price. All of the current shareholders’ shares will be valued at the new share price if new shares are issued at a price that is lower than the price at which the shares were distributed to existing shareholders. This approach is sometimes referred to as the “full ratchet” technique. And on the other hand, when calculating how much to charge for current owners’ shares, the weighted average technique takes into consideration the number of shares that were given away at a cheaper price. This is done so that the price can be more accurately determined.

CONTRACTUAL ANTI–DILUTION ADJUSTMENT

The business and its present shareholders have reached an agreement in order to put an end to the contractual anti-dilution fix. According to this part, the corporation is fine with selling more shares to purchasers provided that the buyers may maintain the same total number of shares that they already possess in the company. Because the issuance of new shares will not have the effect of diluting the ownership stakes of existing shareholders, the latter do not need to be concerned about the possibility of this occurring in the future.

IMPORTANCE OF ANTI–DILUTION ADJUSTMENT CLAUSE

Importance of anti-dilution adjustment clause are as follows:

- Protects investor equity

Every shareholder harbors the hope that the value of their shares will rise, but owing to various conditions in the market, their expectations are sometimes dashed, which puts their ownership in jeopardy. When the corporation issues more shares to investors, it shields the current shareholders from liability, and it also shields the investors from the risks associated with the market.

- Protects the company

Existing shareholders stand to profit from anti-dilution measures, but the corporation as a whole also stands to gain from having these rules in place. When a firm issues new shares to investors at a price that is lower than the original investment, this leads in an increase in the capital for growth, which enables the company to perform better. In addition, the investors get the new shares at a discount.

SEBI’S VIEW AND PROBLEMS LINKED WITH ANTI–DILUTION PROTECTION

SEBI’S views

The Securities and Exchange Board of India has spoken out firmly against plans to loosen regulations on the stock exchange’s list of small and medium-sized businesses.

Problems

According to Indian law, there are a few logistical hurdles that must be overcome before moving on to the next level of the ratchet mechanism. In the complete ratchet mechanism, the shares are issued without any additional payment from the current owners. However, according to the Indian company legislation, the firm is not allowed to issue shares at a discount to its shareholders. As a result, it is not conceivable for a firm to issue more at no additional expense to the shareholders who already have it. There is a potential for conflicts of interest for board members who represent investors in the event of a down round. This is due to the fact that directors are in a position to negotiate the conditions of a down round on behalf of investors and are also required to provide their approval to the transaction as part of their duties as directors.

CHAPTER III: JURISPRUDENCE SURROUNDING ANTI-DILUTION CLAUSES

This chapter specifically deals with legal precedents and court decisions shaping the interpretation and enforcement of anti-dilution clauses and comparative analysis also to get a clearer picture of the anti-dilution scenario. Firstly, the concept of preemptive rights is discussed. After that, the comparative analysis and the modus operandi of these rights are discussed.

PREEMPTIVE RIGHTS

In the last piece, we went through some of the fundamental words that are associated with term sheets, such as raise, dilution, pre- and post-money valuation, and runway. We decided to save the jargon for the next pieces in this series. The concept of “pre-emptive rights” is one that will be examined in depth over the course of this piece.

WHAT ARE PRE–EMPTIVE RIGHTS?

Existing shareholders have the right to preserve their percentage of ownership in a company even if there is a subsequent issuance of shares that takes place before any shares are offered to new investors. This is known as the right to maintain proportional ownership. Anti-dilution rights are another name for this concept.

If the current shareholder chooses to exercise these rights and subscribe to further shares, the new investor will only be granted access to the remaining shares that are up for grabs.

Existing shareholders will get certain rights as a result of these arrangements, but they will not be required to purchase any more shares.

WHY DO VCS WANT THESE RIGHTS?

Venture capitalists often want equity stakes in the businesses they back. They would want to keep their ownership stake in the firms they invested in at the same level.

In addition to this, venture capitalists want the chance to invest additional money in companies that are successful. If a venture capital firm has already invested in, say, 25 different firms, and 5 or 6 of those companies start progressing to higher rounds of funding, the VC firm would want the opportunity to spend additional money in those companies since it is obvious that those companies are succeeding. They would want to increase their wagers on their winning hands.

Additionally, it sends a positive message to potential investors by demonstrating the level of confidence already held by current investors in the business by which they want to invest.

But not just that. In the event that there is a down round (at a value that is lower than the valuation of the previous round), venture capitalists who still believe in the company would want to have the first chance to purchase more shares at a lower price in order to keep their ownership stake in the company.

STATUS OF THE PRE–EMPTIVE RIGHTS ACROSS INDIA, USA & EUROPE?

A. India

Section 62 of the Companies Act of 2013 includes provisions for pre-emptive rights, which are more often referred to as the “right issue” in India. This provision was added in 2013. According to a note that may be found on the website of the Institute of Company Secretaries of India (ICSI), the pre-emptive rights are only accessible to the equity shareholder and not to the preference shareholder. This view of the law is based on the interpretation of the law that the pre-emptive rights are available to. Therefore, it is usually recommended that the investor include it directly as a part of the agreement.

B. The USA

The right is also recognized in the United States. It is typical practice in the United States to provide an incentive to early investors in the form of the preemptive right provision in exchange for the risks that early investors face when funding a new enterprise. In the United States, shareholders seldom have the opportunity to use this power. As a matter of law, a few of states give preemptive rights; nevertheless, even these rules permit a business to waive this right in the articles of incorporation that it files with the state.

C. Europe & Britain

Preemptive rights for purchasers of common stock are not required by law in all jurisdictions, but they are in effect in the nations that comprise the European Union as well as in Great Britain.

D. How do these rights operate?

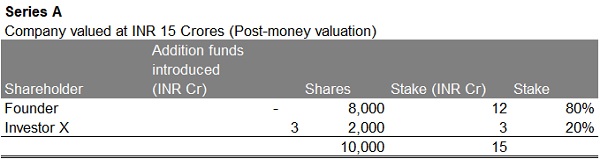

Let’s say this is what the company’s capitalization table (Cap table) looks like right now10:–

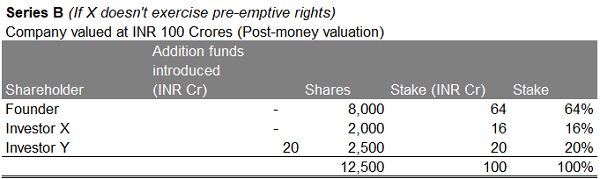

Investor Y is interested in your business and is willing to invest INR 20 Crores to get a 20% share. This gives your company a post-money value of INR 100 Crores.

The new cap table will look like this if current shareholder Investor X doesn’t use his right to buy in first11:-

So, you can see that Investor X’s Stake in the Company drops from 20% to 16%. That is, Investor X’s stake in the company was reduced when new Investor Y bought more shares.

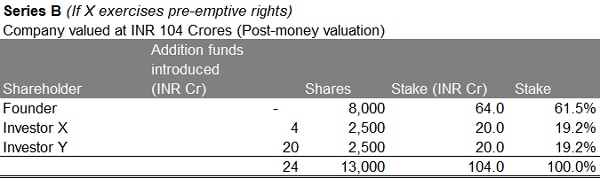

The cap table will look like this if Investor X (an existing Shareholder) uses his right to buy before anyone else does: –

That’s why you can see that Investor X put in an extra 4 Crores to keep its 20% stake in the company. New investor Y is putting in INR 16 crores instead of INR 20 crores.

Investor Y could also put in INR 20 crores, which would make the total amount raised INR 24 crores instead of INR 20 crores. This will mean that the founder will lose even more money, and the cap table will look like this:-12

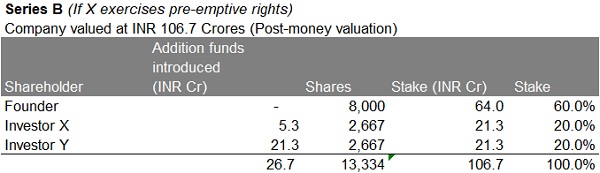

In such a scenario, they may have a total round of INR 26.7 Crores, with the distribution shown in the cap table, in order to retain their 20% ownership13–

RENUNCIATION OF RIGHTS UNDER INDIAN LAW

In accordance with Indian legislation (The Companies Act, 201314), pre-emptive rights include the right to renounce, provided that this power is not prohibited by the articles of the company. The shareholder may renounce any or all of the rights issue shares in favor of another person, and that person does not necessarily have to be an existing shareholder of the company in order for this to be allowed.

Both public and private corporations have the ability to include in their articles of incorporation appropriate clauses that limit or prohibit shareholders’ rights to renounce their rights shares. We recommend including these limits in the Articles of Association for the organization.

CASE STUDY OF PHARMEASY

API Holdings, the company that owns PharmEasy, reportedly made the decision to conduct a rights issue of between Rs 2,000 and Rs 3,000 crore at an all-investor meeting that took place on July 17. This information was provided to CNBC-TV18 by individuals who have personal knowledge of the situation. According to the sources, the request made by the Manipal Group to invest the remaining money has been approved by the parent company of PharmEasy. This will take place in the event that not all investors opt to engage in the venture.

Reportedly, the board of directors of API Holdings has decided to accept the binding offer made by Manipal Group, but only if the company’s existing shareholders decide not to take part in the transaction. Reports indicate that the family office of the Manipal Group has offered to invest up to 1,300 crores of rupees. Depending on the total amount of cash that is raised, it is predicted that the post-money worth of the company would fall somewhere in the region of 6,000 to 7,000 crore.

Very complicated! Pharmeasy is definitely a piece of work that lacks organisation and is inconsistent. Goldman Sachs is owed a total of 2,500 crore rupees by Pharmeasy. It hopes to get between 2,000 and 3,000 crores from its existing investors. In the event that these investors are unable or unable to pay the whole amount, Pharmeasy has decided to sell its stake to Manipal Group, an investor who does not at this time engage in the venture. Manipal anticipates spending 1,300 crore on a project with an estimated value of between 6,000 crore and 7,000 crore ($730 million and $850 million).

Pharmeasy finished its most recent funding round at a value of $5.6 billion in 201615, which took place two years ago. It will now cost somewhere around $800 million, which is a reduction of 85%. Raising funds from investors at a valuation that is lower than your last investment round is referred to as a “down round,” and it is sometimes frowned upon in the startup community. This is because, in part, aesthetic considerations played a role. If the value of a company in which a venture capital fund has invested falls, the fund is obligated to disclose to its own investors that it has experienced a loss as a result of the situation. This is not an attractive sight at all. Nevertheless, there is one reason for the taboo that is more grounded in reality: down rounds effectively remove the company from the control of more experienced investors.

According to recent reports, PharmEasy intends to repay the debt it received from Goldman Sachs by selling rights in order to generate around 2,400 crores. The price of the rights will be ninety percent less than what the previous valuation of the firm was. According to an article published by Tech Crunch16, Grover was quoted as saying that the fresh round of fundraising at a significantly lower valuation, which is often referred to as a “down round,” might have negative impacts on the owners as well as the employees because of the anti-dilutive law17.

The entrepreneur who appears on the Indian version of Shark Tank tweeted the following: “Down Round + Anti-Dilution Clause = Sudden Death for the Founders!”

In light of these circumstances, the anti-dilutive rule will come into play. Those venture capitalists who purchased PharmEasy shares at a higher price (more than 5 euros per share) will get additional shares, reducing their average cost per share down to 5 euros.

Therefore, even the venture capital investors who purchased shares during the most recent round of financing at a price of £55 per share would get 10 times as many for free, lowering their average cost of maintaining shares down to £5 apiece. However, this does imply that both the executives of the firm and the employees will have a considerably lesser portion in the company. It is possible that the stock rights of the company’s founders and members of the Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP) might be reduced to an extremely insignificant level, such as 0.001%.

CHAPTER IV: PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS OF ANTI-DILUTION CLAUSES

WHEN THE ORIGINAL OWNER INVESTS MONEY INTO THE COMPANY, DOES HE/SHE DO SO BASED ON ITS PREVIOUS WORTH OR ITS CURRENT VALUE?

If the previous investor were allowed to put money in at the previous value, it would be unjust to the firm, since the company would get less money, as well as to the new investor, because the new investor would be paying a lot more for the same share.

However, if the new value is lower than the previous value, such as INR 10 Crores instead of INR 100 Crores in the scenario described above, it would be unjust to the existing owners since it would require them to pay more than the current value for new shares.

A price reduction may be applied to the pre-emptive shares if that is what the start-up and Investor X have agreed to do. This is something that will be determined by the stipulations of the share purchase agreement.

THESE RIGHTS ARE ALTERED AS A RESULT OF THE FOLLOWING PROVISIONS IN THE TERM SHEETS:

It would seem that the legislation in India grants them that right; however, views vary as to whether or not these rights are exclusively granted to stock owners or also to preference shareholders. It is possible that both types of shareholders are entitled to them. When entering into a business transaction, it is usually best for the owner to include a separate clause in the agreement that protects these rights.

Super-pro-rata rights are something that the founders of a company need to be aware of. In the event that Investor X purchases shares, the shareholder agreement may be amended to incorporate a right that is superior to the pro rata distribution. Because they have this right, they are able to increase their shareholding in subsequent rounds, for instance from 20% to 25%. In this scenario, the founder’s portion in the company would be reduced further. If the founder is preparing a share purchase agreement or a shareholder agreement, they could wish to oppose this condition so that they don’t lose too much in subsequent rounds of the competition.

Waiver of legal rights: Before a venture capitalist will allow an angel investor to participate in a start-up firm as an investor, the venture capitalist may demand the angel investor to sign away their option to purchase the company. The clause might read something along the lines of “The Company and Promoters shall provide copies of waivers from the Angel Investors of their preemptive right under Clause 7 of the shareholders’ agreement dated XXX and waiver of any claim for any breaches, damages, losses, or otherwise against the Company under the said shareholders’ agreement.”

PROS AND CONS WITH ANTI–DILUTION PROTECTION

Anti-dilution protection, which prevents investors against dilution in the event of a later downturn, makes it simpler to raise more capital via investment. This is beneficial for the firm as well as the venture capitalist, who may have overvalued the company but now has the ability, owing to the anti-dilution protection, to pass the risk of this mistake to the company’s founders as well as other shareholders who are not covered. This is beneficial to the firm because it provides an instrument inside the initial investment structure that enables the company to get more capital in the future. The fact that a high number of “anti-dilution shares” are issued in connection with the investment, however, might be contested by a subsequent investor, which means that anti-dilution protection may also make it impossible for further investment rounds to take place.

As a result, anti-dilution protection will need additional investor agreements, assuming it does not completely negate the necessity for such agreements. Another basis for anti-dilution protection is the fact that the venture capitalist made a certain amount of investment in the company with the idea that it represented a given percentage of the company. This ratio needs to be stable and unaffected by the choices made by the organization at all times. In addition, an investor who just makes monetary contributions to the company without actively engaging in it does not have the same amount of control and influence over the company’s operations and the success of the firm as the company’s founders and the management team has. Because of this, it is appropriate to safeguard the investor in the case that the value of the firm drops. On the other hand, one would retort that a slowdown in the economy represents a threat to the company. Since there is no promise that the ownership fraction would stay the same, the investor should not be given preferential treatment over the company’s founders and other shareholders.

Why should the firm, and especially the founders, be held liable for the mistake in judgement made by the relevant investor? A downturn may show that the investor overvalued the business, but why should the company be held accountable? A course of action that is more logical and sensible would be to give the investor the opportunity to judge for themselves how much the firm is worth. Half a dozen According to the people who developed the formula, the “broad-based weighted average formula” is the most effective anti-dilution formula. The drastic drop in their ownership percentage is mitigated by the fact that this estimate takes into account the number of shares that were sold at the discounted price. From the perspective of the investor, the formula that provides the highest level of protection for the investment is, without a doubt, the superior choice; nevertheless, as we will see in the next discussion, this does not always refer to “the full ratchet.” Even though it provides a very high level of protection, “the full ratchet” may not be the best choice. If an investor does not also get a real and quantifiable return on their investment, the installation of a provision known as a “full ratchet” has the potential to eliminate the motivation for managers and business owners to act in a manner that is beneficial to the firm. This demotivating influence is often the consequence of the adoption of a clause that dramatically diminishes the ownership of the founders; nonetheless, it is possible for this to occur even with a little loss in value. Given the current status of the market and the ongoing decline in value, the anti-dilution precaution will most likely be implemented at some point in the near future, regardless of the development and profitability of the individual company.18

In addition, “the full ratchet formula” has the potential to destroy the bond that exists between investors and entrepreneurs by including elements of mistrust. A decrease in the subscription price may lead to a rise in the investor’s percentage ownership of the company. Furthermore, in a subsequent investment round, the entrepreneurs may consider that a lower valuation of the company is in the investor’s best interest since the investor is fully protected against any potential losses. In addition, the process of assigning a value to a company is sometimes highly influenced by both existing investors and prospective investors. As a result, the founders may argue that the investors behaved dishonestly throughout the discussions and that the firm’s down round value was too low and did not adequately represent the company’s market worth. Additionally, the founders may argue that the down round valuation of the company was too low. Because they have the capacity to seriously damage the entrepreneurs’ morale, “diverging-interests disputes” have the potential to have a detrimental influence on the operations of the firm, future values, and the chance of making a successful exit and investment19.

The connection between investors could also suffer as a result of the fact that, depending on when they invest, investors might be in a variety of possibilities and positions to negotiate from. When making a request for a “full ratchet,” an investor has to keep in mind that succeeding investors will almost certainly need the same level of protection. This might be problematic in the event that the investor’s protection is not triggered, but the protection of other investors is; in such scenario, the investor in question would experience a considerable dilution of their investment20.

Even when the market has made a full recovery, the investor may still incur losses as a result of the implementation of too stringent regulations. In the past, a significant aspect of venture capital investments was to match the interests of the investors and management. This was accomplished by providing managers and other important staff members with the opportunity to earn a substantial stock upside in the event of an initial public offering (IPO) or a lucrative exit from the company. In addition, investors were given the opportunity to get a return on their investment. If these laws are put into effect, employees will quickly find that there is a very little probability that they will get any remuneration for the equity they have earned. These managers and workers may be required to continue working for the firm given the present state of the economy; but, once things start to improve, there is little question that they will search for employment elsewhere where they can make higher returns on their stock investments. They have already sacrificed higher income in exchange for equity21.

The use of “the full ratchet” by a significant investor in a syndicated venture might make problems more difficult to address rather than finding a solution to them. Since the value of each fund’s shares is totally protected against falling prices, there is no need to invest in a fund that is experiencing a decline since there is no incentive to do so. At this crucial moment in the company’s financial requirements, the business regards this as a key problem that has to be addressed. Because each potential new investor will be aware of the ratchet in its entirety, the company will lose its attraction to them as an investment option. After an initial round of investors has successfully obtained full ratchet protection, following investors are likely to want the same degree of security; hence, full ratchets are likely to be applicable to all future rounds of investment as well. Under these circumstances, funds that have already made a modest investment in the company have the option of deciding not to make any more investments. They will not suffer a significant financial setback as a direct result of the failure of the firm.

However, things may be different for the top investor since they would be required to take part in the down round in order for the company to continue operating successfully. In circumstances in which there is no equity value, the lead investor can be required to supply more cash to the company if the other funds in the syndicate refuse to give up their anti-dilution protection in return for an increased percentage ownership for doing nothing22. In spite of this, there are situations in which the use of a “full ratchet” might be considered appropriate. This is particularly true for newly established companies that are searching for their first round of capital at a high valuation. Investors who are concerned about this value or the closing of the market window may still choose to take part in the company if they are offered protection in the form of a “full ratchet” or, at the very least, a time-limited ratchet. A “full ratchet” may also protect the venture investor in the event that more investment is necessary, acting as insurance against the occurrence or non-occurrence of specific future events, such as the acquisition of a patent. Because it takes into consideration the current state of the economy in which the company operates, “the market price formula” seems to be a more realistic approach to take. Because, in contrast to “the traditional formulas,” this makes necessary financing rounds feasible even during challenging periods when the market price is lower than the original subscription price, it may be the best course of action from the company’s point of view to choose this particular course of action.

Nevertheless, “the market price approach” is not used very often. One such explanation is the difficulty of coming to an agreement on what constitutes a reasonable price in the market. The purpose of the formula for the market price is to arrive at a price that is unaffected by the subsequent sale of rights. However, since a right offering is sometimes preceded by speculations and leaks about the anticipated move, it may be difficult to get a market price that has not been affected in any way by the intended action. In addition, the stakeholders of the firm, such as the management team, may try to manipulate the market price by operating in a manner that is conducive to serving their own interests in order to achieve their goals. However, the primary reason why this approach is probably not used very often is that there is no market value since so few shares of venture capital-supported companies are listed on public markets. This is probably the reason why this method is not used very frequently.

CHAPTER V: CONCLUSION AND SUGGESTIONS

Since it was simpler to negotiate this protection than to implement it, there may be some legal and regulatory complications associated with enforcing it. A foreign investor who wishes to use their right against dilution must first be informed of the price parameters that have been established under the Foreign Exchange Management (Non-debt Instruments) Rules, 2019 (referred to henceforth as the “ND Rules”). The price at which shares of an Indian company that is private or not listed to the public may not be less than the fair market value of those shares, as determined by any internationally recognized pricing methodology and duly certified by a Chartered Accountant, a Merchant Banker, or a practicing Cost Accountant. According to these rules, the price at which shares may be purchased may not be less than the fair market value of those shares23. Because of this, it would be difficult to issue shares to a non-resident “free of cost” or at any price that is lower than their current worthwhile yet retaining a protection against dilution.

The ND Rules require, in addition, that the price and conversion formula of any convertible instrument be determined in advance at the time of issuance, and that in no circumstance may the price at which a conversion takes place be lower than the equity shares’ determined fair market value at the time the convertible instrument is issued. This requirement applies to all instances. It is possible that any changes to the conversion formula that are regarded to offer anti-dilution protection may become even more problematic as a result of the fact that the conversion price can never go below the fair value of the equity shares at the time of issuance.

Any issuance of shares at a price that is lower than the shares’ fair market value, with the exception of rights issuances, may also fall within the purview of section 56(2)(x)(c) of the Income Tax Act of 196124. This section defines “income from other sources” as the difference between the discounted value and the fair market value, which is computed using the book value of assets minus liabilities. In other words, “income from other sources” is the difference between the discounted value and the fair market value. On top of that, the acquirer could have to pay taxes at a rate of forty percent on the difference. In order to assist ensure that the anti-dilution right is implemented appropriately moving ahead, there are a few proactive steps that might be performed.

Ensuring that the price of shares with anti-dilution protection is issued at a price that is sufficiently higher than the fair market value today is one approach to assure that any revision to the conversion price after dilution will still comfortably surpass the then-current fair market value. India is one of the few developing nations that does not have a legal and regulatory structure that is as clear cut as those found in most industrialized countries, particularly in regard to unlisted shares. Investors in other countries are mulling about the possibility of implementing further price protection measures. One of these variations is called “Golden Shares,” and it provides investors with a lesser ownership position to begin with. However, Golden Shareholders are guaranteed preferred rights in the case of anti-dilution or liquidity events, giving them an advantage over other shareholders. Even for a provision that is used regularly, it is not expected that draughtsman will be interested in studying the specifics of an anti-dilution formula and how it fluctuates based on the ads, even if the provision is used frequently25. Higher information barriers in development or intermediate-stage private investment firms are one of the primary aspects that play a role in determining whether or not to choose the anti-dilution privilege as an option. An investor is more likely to overvalue his investment in a privately owned firm when compared to an investment in a publicly listed corporation that is carefully regulated26.

This is because access to information may be skewed, limited, or even fraudulent in the privately held company. By learning this mathematical formula and identifying any blind spots in an early-stage investment, one may increase the sophistication of an anti-dilution precaution, making it more likely that it will be easier to put into practice in the future.

When deciding whether or not to exercise their anti-dilution rights, investors often take a variety of factors into consideration. These factors may include the possible impact on the management team as well as the ability to raise money in the future. The Reserve Bank of

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BOOKS

- Barlett, Fundamentals of venture capital (first published 1999) 3

- De la Dehesa, Venture capital in the United States and Europe (2002) 3 JOURNALS

- Andretzky, F., Ramsay, I., ‘Preferential investments in Sweden’ (2002) IFLR 21(1)

- Carter, Hoyt, “US venture capital terms: moving towards new standards?” (2001) IFLR 1

- Davis, Drake, “Protecting the private equity investment without killing the golden goose” (2003) IFLR 119

- Gent, D., Tarala of Brobeck, T., ’Towards a unified approach to cross-border venture capital documentations’ (2001) IFLR

- Michael A. Woronoff, Jonathan A. Rosen, ‘Understanding Anti-Dilution Provisions’ (2005) 74 FLR

- Murphy, M., ‘New-look investment for the technology comeback’ (2003) IFLR 22

- Sokol, A., Small, R., Meredith, S., Cole, J., ‘Down rounds – to succeed you must survive’ (2002) IFLR

- Tom Hockaday, Tony Hickson, ‘Golden Shares and Anti-dilution Provisions’ (2015) OUI

WEBSITES

- ‘PharmEasy new funding round ‘sudden death’ for founders: Ashneer Grover’ (The Hindustan Times, 6 July 2023) <https://www.hindustantimes.com/business/ashneer-grover-predicts-sudden-death-for-pharmeasy-founders-over-new-funding-round-101688641345538.html> accessed 8 October 2023

- Atikant Kaur, Aishwarya H., Parag Srivastava, Pratibha Jain, ‘Cracking the Anti-Dilution Formula’ (Nishith Desai Associates, June 2020) <https://www.nishithdesai.com/Content/document/pdf/Hotline/Cracking-the-Anti-Dilution-Formula.pdf> accessed 3 October 2023

- Bruno, ‘The Anti-Dilution Clause under the Portuguese Law’ (Tilburg University, June 2018) <http://arno.uvt.nl/show.cgi?fid=146926> accessed 4 October 2023

- Digbijay, Samidha, ‘PharmEasy plans Rs 2,400-crore rights issue at 90% discount to repay loan’ (The Economic Times, 6 July 2023) <https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/tech/startups/pharmeasy-plans-rs-2400-crore-rights-issue-at-90-cut-in-share-price/articleshow/101510154.cms?from=mdr> accessed 28 September 2023

- Hutchison and Mason PLLC, ‘Structuring Venture Capital Investments’ (ZeroMillion.com, 2 November 2005) <http://www.zeromillion.com/entrepreneurship/structuring-venture-capital-investments.html> accessed 1 October 2023

- Manish Singh, ‘PharmEasy, once valued at over $5 billion, seeks new funding at a 90% valuation cut’ (Tech Crunch, 5 July 2023)<https://techcrunch.com/2023/07/05/pharmeasy-valuation-cut/> accessed 29 September 2023

- Paul Albert, Ashwin Bhat, ‘Anti-Dilution Protection In Shareholders Agreement – Implementation Under Indian Laws’ (Mondaq, 1 November 2018) <https://www.mondaq.com/india/shareholders/750920/anti-dilution-protection-in-shareholders-agreement–implementation-under-indian-laws> accessed 4 October 2023

- Revathy Muralidharan, Aakash Dasgupta, Aditi Rani, ‘Infolex Article: Understanding Anti-Dilution Rights in Indian Investments’ (IndusLaw, 8 July 2020) <https://induslaw.com/publication/448/infolex-article-understanding-anti-dilution-rights-in-indian-investments > accessed 2 October 2023

- Revathy, Aakash, Aditi, ‘Understanding Anti-Dilution Rights in Indian Investments’ (IndusLaw, 8 July 2020) <https://induslaw.com/app/webroot/publications/pdf/alerts-2020/Infolex-Article-Anti-Dilution-July-8-2020.pdf> accessed 2 October 2023

STATUTES

- Companies Act, 2013

- Foreign Exchange Management (Non-debt Instruments) Rules 2019

- Income Tax Act 1961

Notes:

1 Revathy Muralidharan, Aakash Dasgupta, Aditi Rani, ‘Infolex Article: Understanding Anti-Dilution Rights in Indian Investments’ (IndusLaw, 8 July 2020) <https://induslaw.com/publication/448/infolex-article-understanding-anti-dilution-rights-in-indian-investments > accessed 2 October 2023

2 Atikant Kaur, Aishwarya H., Parag Srivastava, Pratibha Jain, ‘Cracking the Anti-Dilution Formula’ (Nishith Desai Associates, June 2020) <https://www.nishithdesai.com/Content/document/pdf/Hotline/Cracking-the-Anti-Dilution-Formula.pdf> accessed 3 October 2023

3 Bruno, ‘The Anti-Dilution Clause under the Portuguese Law’ (Tilburg University, June 2018) <http://arno.uvt.nl/show.cgi?fid=146926> accessed 4 October 2023

4 Paul Albert, Ashwin Bhat, ‘Anti-Dilution Protection In Shareholders Agreement – Implementation Under Indian Laws’ (Mondaq, 1 November 2018) <https://www.mondaq.com/india/shareholders/750920/anti-dilution-protection-in-shareholders-agreement–implementation-under-indian-laws> accessed 4 October 2023

5 Barlett, Fundamentals of venture capital (first published 1999) 3

6 De la Dehesa, Venture capital in the United States and Europe (2002) 3

7 Hutchison and Mason PLLC, ‘Structuring Venture Capital Investments’ (ZeroMillion.com, 2 November 2005) <http://www.zeromillion.com/entrepreneurship/structuring-venture-capital-investments.html> accessed 1 October 2023

8 Carter, Hoyt, “US venture capital terms: moving towards new standards?” (2001) IFLR 1

9 Davis, Drake, “Protecting the private equity investment without killing the golden goose” (2003) IFLR 119

10 Revathy, Aakash, Aditi, ‘Understanding Anti-Dilution Rights in Indian Investments’ (IndusLaw, 8 July 2020) < https://induslaw.com/app/webroot/publications/pdf/alerts-2020/Infolex-Article-Anti-Dilution-July-8-2020.pdf > accessed 2 October 2023

11 Revathy, Aakash, Aditi, ‘Understanding Anti-Dilution Rights in Indian Investments’ (IndusLaw, 8 July 2020) <https://induslaw.com/app/webroot/publications/pdf/alerts-2020/Infolex-Article-Anti-Dilution-July-8-2020.pdf > accessed 2 October 2023

12 Revathy, Aakash, Aditi, ‘Understanding Anti-Dilution Rights in Indian Investments’ (IndusLaw, 8 July 2020) <https://induslaw.com/app/webroot/publications/pdf/alerts-2020/Infolex-Article-Anti-Dilution-July-8-2020.pdf > accessed 2 October 2023

13 Revathy, Aakash, Aditi, ‘Understanding Anti-Dilution Rights in Indian Investments’ (IndusLaw, 8 July 2020) <https://induslaw.com/app/webroot/publications/pdf/alerts-2020/Infolex-Article-Anti-Dilution-July-8-2020.pdf > accessed 2 October 2023

14 The Companies Act, 2013

15 Digbijay, Samidha, ‘PharmEasy plans Rs 2,400-crore rights issue at 90% discount to repay loan’ (The Economic Times, 6 July 2023) <https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/tech/startups/pharmeasy-plans-rs-2400-crore-rights-issue-at-90-cut-in-share-price/articleshow/101510154.cms?from=mdr> accessed 28 September 2023

16 Manish Singh, ‘PharmEasy, once valued at over $5 billion, seeks new funding at a 90% valuation cut’ (Tech Crunch, 5 July 2023) <https://techcrunch.com/2023/07/05/pharmeasy-valuation-cut/> accessed 29 September 2023

17 ‘PharmEasy new funding round ‘sudden death’ for founders: Ashneer Grover’ (The Hindustan Times, 6 July 2023) <https://www.hindustantimes.com/business/ashneer-grover-predicts-sudden-death-for-pharmeasy-founders-over-new-funding-round-101688641345538.html> accessed 8 October 2023

18 Sokol, A., Small, R., Meredith, S., Cole, J., ‘Down rounds – to succeed you must survive’ (2002) IFLR

19 Gent, D., Tarala of Brobeck, T., ’Towards a unified approach to cross-border venture capital documentations’ (2001) IFLR

20 Murphy, M., ‘New-look investment for the technology comeback’ (2003) IFLR 22

21 Andretzky, F., Ramsay, I., ‘Preferential investments in Sweden’ (2002) IFLR 21(1)

22 Andretzky, F., Ramsay, I., ‘Preferential investments in Sweden’ (2002) IFLR 21(1)

23 Foreign Exchange Management (Non-debt Instruments) Rules 2019 Rule 21(2)(ii)

24 Income Tax Act 1961, s 56(2)(x)(c)

25 Tom Hockaday, Tony Hickson, ‘Golden Shares and Anti-dilution Provisions’ (2015) OUI

26 Michael A. Woronoff, Jonathan A. Rosen, ‘Understanding Anti-Dilution Provisions’ (2005) 74 FLR