Case Law Details

Knitpro International Vs Examiner of Trade Marks (Delhi High Court)

Settled legal position is that in order for a shape trademark to be registered, it has to be shown that the said shape is not the generic shape of the product. It has to be a distinctive shape that associates the mark with the source by itself without anything further like a name or logo appended on it. The shape must have lost its inherent or generic meaning and ought to have acquired a secondary connotation. The standard of distinctiveness required to be acquired would be quite high.

Having recorded the legal position on shape marks, since the Appellant wishes to withdraw the appeal, the same is dismissed as withdrawn. All pending applications are also disposed of. The rejection of trade mark application bearing no. 2735618 in Class 26 in respect of knitting needles and crochet hooks, is accordingly not interfered with and is upheld.

FULL TEXT OF THE JUDGMENT/ORDER OF DELHI HIGH COURT

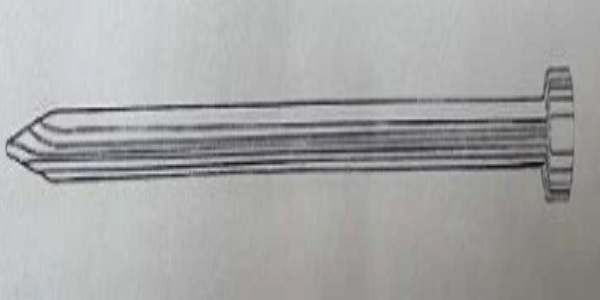

1. The present appeal challenges the impugned order dated 26th September, 2019 passed by the Senior Examiner of Trade Marks by which the trademark application of the Appellant bearing no. 2735618 for the registration of shape of a knitting needle in Class 26 in respect of ‘knitting needles and crochet hooks’ was rejected. The image of the knitting needle sought to be registered is extracted below:

2. The application of the Appellant was found to be objectionable under Sections 9(1)(a) and 9(1)(b) of the Trade Marks Act, 1999 (hereinafter ‘Act’) and the mark was found to be devoid of any distinctive character by the Senior Examiner.

3. counsel for the Appellant submits that the shape of the knitting needle sought to be registered by the Appellant is very distinctive and has acquired secondary meaning. Mr. Harish V Shankar accepts notice.

4. The court has put to the ld. Counsel, as to what are the distinctive elements in the above needle that entitle it to a shape trade mark protection. Ld. Counsel after seeking instructions submits that he wishes to withdraw the present appeal. Thus, on facts, the appeal is dismissed as withdrawn.

5. This Court, however, for the purposes of recording the legal position on shape trademarks, notices that the erstwhile Trade and Merchandise Marks Act, 1958 defined the word ‘mark’ under section 2(1)(j) as under:

(j) “mark” includes a device, brand, heading, label, ticket, name, signature, word, letter or numeral, or any combination thereof;

6. The Trade Marks Act, 1999 expanded the definition of `mark’ and provides an illustrative definition of the word ‘mark’ in section 2(1)(m) in the following manner:

(m) “mark” includes a device, brand, heading, label, ticket, name, signature, word, letter, numeral, shape of goods, packaging or combination of colours or any combination thereof;

7. On juxtaposing definitions of the word ‘mark’ under the old and the new trade mark laws, it can be inferred that the scope and meaning of the word ‘mark’ has expanded over time and is no longer limited to what are commonly referred to as traditional trademarks. The law now extends trade mark protection to features such as shape of goods, packaging, sound, smell, and combination of colours amongst others, as long as they fulfil the quintessential function of trademark- ‘source identification’. This Court in Levi Strauss and Co. v. Imperial Online Services Private Limited [CS(COMM) 657/2021 order dated 24th March, 2022] has summed up the evolution of trade marks in the following words:

“14. Under the law of trade marks, the definition of ‘mark’ has evolved over time. Traditionally, trademarks included names, words, devices, logo, label/packaging, letters, numerals etc. However, this list of trademarks has expanded over the years to include colour, combination of colours, shape of goods, patterns of products, smell, and sound marks etc. These broad two categories of marks are loosely referred to as –

-

- Traditional Trademarks

- Non-Traditional Trademarks.

15. The present case relates to a stitching pattern which is not a product design i.e., the design of a product, but a pattern which is incorporated on Plaintiff’s jeans products. The question in such a case would be as to whether mere appearance of the said stitching pattern would perform a trademark function i.e., associate the jeans with the Plaintiff. If the answer to this question is in the affirmative then the pattern would be construed as a trademark deserving protection. There may be a large number of stitching patterns which may be merely for aesthetic or visual appeal. However, when a trademark owner’s stitching pattern per se identifies the jeans, even without a name or a logo, then the intention of the proprietor is for the pattern to perform the function of a trademark. In such a case, the Court would have to examine as to whether the stitching pattern has an ‘acquired meaning’, or is distinctive per se. The test of acquired meaning is similar to the test of secondary meaning applied to descriptive words. In McCarthy on Trademarks and Unfair Competition [4th Ed., Vol.1,], J. Thomas McCarthy while dealing with geometric shapes as trademark formats opines as under:

However, uncommon or unusual shapes and symbols that contain some minimum amount of inventiveness or fancifulness can be regarded as inherently distinctive and protected as such, without the need for proof of secondary meaning. The issue is whether this shape is so unusual for this type of goods or services that its distinctiveness can be assumed.”

8. In McCarthy on Trademarks and Unfair Competition [4th Ed § 8.4, page 8-13], Thomas McCarthy is also of the view that the design and shape of the product can be protected as part of ‘trade dress’. The relevant excerpt is extracted below:

“Traditionally, “trade dress” was thought to consist only of the appearance of labels, wrappers and containers used in packaging the product. However, in modem parlance, “trade dress” includes the total look of a product and its packaging and even includes the design and shape of the product itself.”

9. Generally, the novel shape of a product which has aesthetic appeal is protectable under the law of designs, if the requisite conditions are satisfied. However, under the law of trade marks, the threshold for extending exclusive rights to the shape of a product, is quite high. The shape by itself should immediately be identifiable with the source of the product. For trade mark registration of shape of a product, the same can only be granted if it has acquired a secondary meaning.

10. The Supreme Court of the United Stated in the case of Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Samara Brothers 529 U.S. 205, 120 S.Ct. 1339 was considering an action for infringement of an unregistered product design under the Lanham Act. The Court held that for exclusivity to be granted in design of a product, the Plaintiff must ‘always’ prove that the design has acquired secondary meaning in the market place and it could never be classified as inherently distinctive. The key passages in the judgment of the Court merit citation in full:

“It seems to us that design, like color, is not inherently distinctive. The attribution of inherent distinctiveness to certain categories of word marks and product packaging derives from the fact that the very purpose of attaching a particular word to a product, or encasing it in a distinctive packaging, is most often to identify the source of the product. Although the words and packaging can serve subsidiary functions— a suggestive word mark (such as “Tide” for laundry detergent), for instance, may invoke positive connotations in the consumer’s mind, and a garish form of packaging (such as Tide’s squat, brightly decorated plastic bottles for its liquid laundry detergent) may attract an otherwise indifferent consumer’s attention on a crowded store shelf— their predominant function remains source identification. Consumers are therefore predisposed to regard those symbols as indication of the producer, which is why such symbols “almost automatically tell a customer that they refer to a brand,” id., at 162-163, and “immediately… signal a brand or a product ‘source,’” id., at 163. And where it is not reasonable to assume consumer predisposition to take an affixed word or packaging as indication of source— where, for example, the affixed word is descriptive of the product (“Tasty” bread) or of a geographic origin (“Georgia” peaches)— inherent distinctiveness will not be found. That is why the statute generally excludes, from those word marks that can be registered as inherently distinctive, words that are “merely descriptive” of the goods, §2(e)(1), 15 U. S. C. §1052(e)(1), or “primarily geographically descriptive of them,” see §2(e)(2), 15 U. S. C. §1052(e)(2). In the case of product design, as in the case of color, we think consumer predisposition to equate the feature with the source does not exist. Consumers are aware of the reality that, almost invariably, even the most unusual of product designs— such as a cocktail shaker shaped like a penguin— is intended not to identify the source, but to render the product itself more useful or more appealing.

The fact that product design almost invariably serves purposes other than source identification not only renders inherent distinctiveness problematic; it also renders application of an inherent-distinctiveness principle more harmful to other consumer interests. Consumers should not be deprived of the benefits of competition with regard to the utilitarian and esthetic purposes that product design ordinarily serves by a rule of law that facilitates plausible threats of suit against new entrants based upon alleged inherent distinctiveness. How easy it is to mount a plausible suit depends, of course, upon the clarity of the test for inherent distinctiveness, and where product design is concerned we have little confidence that a reasonably clear test can be devised. Respondent and the United States as amicus curiae urge us to adopt for product design relevant portions of the test formulated by the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals for product packaging in Seabrook Foods, Inc. v. Bar-Well Foods, Ltd., 568 F. 2d 1342 (1977). That opinion, in determining the inherent distinctiveness of a product’s packaging, considered, among other things, “whether it was a ‘common unique or unusual in a particular field, [and] whether it was a mere refinement of a commonly-adopted and well-known form of ornamentation for a particular class of goods viewed by the public as a dress or ornamentation for the goods.” Id., at 1344 (footnotes omitted). Such a test would rarely provide the basis for summary disposition of an anticompetitive strike suit. Indeed, at oral argument, counsel for the United States quite understandably would not give a definitive answer as to whether the test was met in this very case, saying only that “[t]his is a very difficult case for that purpose.” Tr. of Oral Arg. 19.”

11. The Court of Appeal (Civil Division) in Société des Produits Nestlé SA (Nestlé) v. Cadbury UK Ltd. [2017] EWCCA Civ 358 was confronted with an application for the registration of the following three-dimensional mark in respect of chocolates:

12. An appeal was preferred against the order dismissing the application for the registration of the mark. The Court dismissed the appeal. Lord Justice Kitchin while analysing the legal framework for assessing the distinctive nature of marks made the following observation:

“20. There are three other points I should mention at this stage. First, and while it is true to say that the criteria for assessing the distinctive character of all kinds of marks are the same, the CJEU has recognised that the relevant public’s perception is not necessarily the same in the case of a three-dimensional mark consisting of the shape of a product or its packaging as it is in the case of, for example, a word or figurative mark consisting of a sign which is independent from the appearance of the products it denotes. Specifically, average consumers are not in the habit of making assumptions about the origin of products on the basis of their shape or the shape of their packaging in the absence of any graphic or word element, and it may therefore prove more difficult to establish distinctiveness in relation to such a three-dimensional mark than in relation to a word or figurative mark:

see, for example, Case C-136/02P Mag Instrument v OHIM [2004] ECR I-9165 at [30].

21. Secondly, it follows that the more closely the shape for which registration is sought resembles the shape most likely to be taken by the product in question, the greater the likelihood of the shape being devoid of distinctive character: see, for example, Mag Instrument v OHIM at [31].

22. Thirdly, in assessing whether a mark has acquired distinctive character through use, the tribunal must make an overall assessment having regard to all of the relevant evidence and all of the circumstances in which the relevant public may have seen the mark, including, for example, in advertising before a purchasing decision is made, on the product and associated materials at the point a purchasing decision is made, and afterwards, when the product is consumed. Nevertheless, it must also be recognised that the degree of attention of the average consumer may vary from time to time, and that, at least in some cases, it is when making a choice between different products in the category concerned that the average consumer pays the highest degree of attention: see, for example, case C-24/05P August Storck KG v Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market [2006] ECR I5677 at [70] to [72].”

13. Thus, the settled legal position is that in order for a shape trademark to be registered, it has to be shown that the said shape is not the generic shape of the product. It has to be a distinctive shape that associates the mark with the source by itself without anything further like a name or logo appended on it. The shape must have lost its inherent or generic meaning and ought to have acquired a secondary connotation. The standard of distinctiveness required to be acquired would be quite high.

14. Having recorded the legal position on shape marks, since the Appellant wishes to withdraw the appeal, the same is dismissed as withdrawn. All pending applications are also disposed of. The rejection of trade mark application bearing no. 2735618 in Class 26 in respect of knitting needles and crochet hooks, is accordingly not interfered with and is upheld.

15. This shall however not prejudice the Appellant from seeking protection in law for a shape mark, if permissible, at a later stage, upon establishing that the same has acquired a secondary meaning and is hence distinctive.