Case Law Details

Prakash Industries Limited Vs Union of India (Delhi High Court)

Delhi High Court held that power of Enforcement Directorate (ED) stands confined to the offense of money laundering as defined in terms of Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002.

Facts-

These two writ petitions raise an important question relating to the powers of the Enforcement Directorate to provisionally attach properties u/s. 5 of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002 even though no proceedings relating to the predicate offense may have been initiated by the competent agency functioning under an independent statute and in terms of which the scheduled offense stands created. The ancillary and yet equally fundamental issue which the Court is called upon to answer is whether the ED could be recognised to have the jurisdiction to enforce the measures contemplated in Section 5 of the Act solely upon it being of the opinion that the material gathered in the course of an investigation or enquiry evidences the commission of a predicate offense. The questions posited would also raise the ancillary issue of the powers that the ED could be recognised to derive from the Act while investigating an offense of money laundering.

Conclusion-

Held that initiation of action under Section 5 of PMLA is premised on the competent authority having reason to believe that a person is in possession of proceeds of crime. The formation of opinion under the said provision is not related to the commission of a scheduled offence. Property, in order to be recognised even prima facie as being proceeds of crime must necessarily be preceded by ―criminal activity relating to a scheduled offense”. This is also evident from the use of the expressions ―as a result of” and ―derived or obtained” in Section 2(1)(u) of the Act. The evidence of criminal activity would be either a First Information Report, a complaint or a chargesheet as envisaged under various statutes. However, in absence thereof it would be wholly impermissible for the ED to itself become the arbiter of whether a scheduled offense stands committed.

What needs to be emphasised is that the PMLA empowers the ED to investigate Section 3 offenses only. Its power to investigate and enquire stands confined to the offense of money laundering as defined in that Section. However, the same cannot be read as enabling it to assume from the material that it may gather in the course of that investigation that a predicate offense stands committed.

FULL TEXT OF THE JUDGMENT/ORDER OF DELHI HIGH COURT

A. PROLOGUE

1. These two writ petitions raise an important question relating to the powers of the Enforcement Directorate1 to provisionally attach properties under Section 5 of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 20022 even though no proceedings relating to the predicate offense may have been initiated by the competent agency functioning under an independent statute and in terms of which the scheduled offense stands created. The ancillary and yet equally fundamental issue which the Court is called upon to answer is whether the ED could be recognised to have the jurisdiction to enforce the measures contemplated in Section 5 of the Act solely upon it being of the opinion that the material gathered in the course of an investigation or enquiry evidences the commission of a predicate offense. The questions posited would also raise the ancillary issue of the powers that the ED could be recognised to derive from the Act while investigating an offense of money laundering.

2. The writ petitions principally assail the action taken by the ED which had proceeded to pass a Provisional Attachment Order3 dated 29 November 2018. W.P.(C) 13361/2018 came to be instituted on or about 09 December 2018 and at a time when the petitioner was yet to be served with the PAO. The connected writ petition directly assails the order of 29 November 2018 noticed above. The proceedings drawn by the ED emanate from a First Information Report4 bearing RC No. 219 2014 E-0002 dated 26 March 2014 registered by the Central Bureau of Investigation5 and ECIR No. 3 of 2014 which came to be lodged on 29 December 2014 by the respondent. During the pendency of the instant writ petitions, ED also proceeded to file a separate complaint referable to Section 45 of the Act and on which further investigation is still stated to be continuing. Similar is the position insofar as the ECIR is concerned.

3. Turning firstly to the proceedings on the FIR registered at the behest of the CBI, the record would bear out that a Closure Report was submitted before the competent court on 30 August 2014. A protest petition came to be filed by the complainants thereafter on 02 November 2016. Upon the aforesaid protest petition coming to be filed, a prayer was made before the competent court for CBI being accorded permission to conduct further investigation. On the conclusion of that investigation, a chargesheet came to be filled before the competent court on 17 November 2021 against the petitioner and other named accused. The competent court took cognizance on the aforesaid chargesheet in terms of its order of 31 January 2022 and issued summons against the named accused.

4. The aforesaid order was assailed by the petitioner by way of S.L.P (CRL.) Nos. 656–657/2022 and 3360/2022. On the aforenoted Special Leave Petitions, interim orders came to be passed on 06 and 09 May 2022 respectively staying further proceedings before the Special Judge. Those interim orders continue to operate.

5. Insofar as the ECIR is concerned, the Special Judge has in its order of 22 October 2022 noted that as per the ED further time was required to complete investigation. Awaiting a report on conclusion of further investigation, the matter was thereafter adjourned and remains pending at that stage. Similarly on the Section 45 complaint, the order sheet would reflect that the matter has been continually adjourned to enable the respondent to complete investigation.

6. When W.P.(C) 13361/2018 came to be entertained by the Court, the following interim order came to be passed on 08 January, 2019:-

“In view of the order dated 12.12.2018 passed in similar matter in LPA No.588/2018, the adjudicating authority will proceed with the matter but the final order shall not be passed without leave of this Court.

Counsel for the respondents submits that counter affidavit is ready and the same would be filed within two days.

Rejoinder thereto, if any, be filed before the next date of hearing.

Renotify on 15th March, 2019.”

7. On W.P.(C) 4962/2019 an interim order to the following effect came to be passed on 09 May 2019: –

“Issue notice.

Learned counsel accepts notice on behalf of the respondents and seeks time to file counter affidavit.

Let needful be done within a period of six weeks.

Rejoinder thereto, if any, be filed within four weeks thereafter.

Renotify on 21.08.2019.

In view of the order dated 11.01.2019 passed by Hon’ble the Supreme Court in SLP No. 33919-33920/2018, proceeding against the petitioner before the Learned Adjudicating Authority shall remain stayed.

Dasti”

8. By virtue of the aforenoted interim orders, no final orders as contemplated under Section 8 of the Act have come to be passed till date. For the purposes of appreciating the questions which arise for determination, the Court deems it apposite to notice the following essential facts.

9. The proceedings drawn by the ED emanate from an allocation of the Fatehpur Coal Block located in the State of Chhattisgarh. On 13 November 2006, the Ministry of Coal in the Union Government published an advertisement inviting applications for allocation of 38 coal blocks. The petitioner in pursuance of the said advertisement submitted an application dated 12 January 2007 for allotment of the aforenoted coal block. On 06 November 2007 the Union Government apprised the petitioner of it considering the allotment of the coal block. It called upon the petitioner and its joint venture partner to submit options as described in that letter for the purposes of a formal order being drawn. Based on this letter, the petitioner addressed a letter on 17 November 2007 to the Bombay Stock Exchange6 apprising it of the allotment of the Fatehpur Coal Block in its favour. A letter of allocation came to be made in favour of the petitioner and its joint venture partner M/s S.K.S Ispat and Energy. Ltd. on 06 February 2008. On 26 March 2014, CBI proceeded to register an FIR alleging commission of offences referable to Section 120B read with Section 420 of the Indian Penal Code, 18607 along with Sections 13(2) and 13(1)(d) of the Prevention of Corruption Act, 19888. The said FIR alleged that the petitioner had actively misrepresented in its application for allocation of a coal block insofar as disclosures with respect to net worth were concerned. It was specifically alleged that while the application had set out the net worth of the petitioner as being Rs. 532 crores, in the course of enquiry it came to light that its actual net worth was Rs. (-)144.16 crores at that time. It was further alleged that despite the Ministry of Power having not framed any positive recommendations in favour of the petitioner, the Screening Committee constituted by the Ministry of Coal in its meeting held on 13 September 2007 recommended the allocation of the coal block in favour of the petitioner along with its joint venture partner. Following close on the heels of the said FIR being registered, the ED lodged the ECIR on identical allegations. The said ECIR upon noticing the substratal facts which formed the bedrock of the FIR lodged by the CBI proceeded to record that on the commission of the aforenoted criminal offences, the respondent have reason to believe that proceeds of crime had been generated.

10. It becomes relevant to note at this juncture that the allocation of the Fatehpur Coal Block in favour of the petitioner ultimately came to be cancelled in light of the judgment rendered by the Supreme Court in Manohar Lal Sharma vs. The Principal Secretary & Ors.9 It was after the aforesaid judgment had been rendered on 24 September 2014 that the ECIR came to be registered.

11. As was noticed in the preceding parts of this decision, the ECIR undisputedly came to be registered after a final report had come to be submitted by the CBI before the Special Judge on 30 August 2014. While further investigation was continuing both in respect of the FIR as well as the ECIR, on 17 July 2018 a complaint came to be lodged by ED asserting it to be one under Section 45 of the Act. Upon its institution, the Special Judge on the same day at 6:15 PM proceeded to pass the following order:-

“CRC NO.

ECIR/03/CDZO/2014

Directorate of Enforcement Vs. M/s Prakash Industries Ltd.

and Ors.

U/s. 3&4 PMLA, 2002

Fresh prosecution complaint u/s 45 PMLA, 2002 has been filed by IO Assistant Director Sh. Santokh Singh, ED, Chandigarh.

It be checked and registered.

At 06.15 pm

17.07.2018

Present: Ld. Special P.P Sh. N.K. Matta and Ld. Special PP Ms. Tarannum Cheema for Directorate of Enforcement along with IO Assistant Director Sh. Santokh Singh.

Upon enquiry about the facts and circumstances of the case and the consequent investigation carried out in the matter it was submitted that though further investigation in the matter is still being carried on but the urgency to file the complaint arose on account of the recent amendment in section 8 of PMLA, 2002 wherein any attachment, if effected can be continued only if some proceedings are pending before a Court.

Heard. Perused.

As a number of queries raised by the Court have remained unanswered so it is directed that IO shall produce the case file on the next date as he states that no case diary is maintained by ED during the investigation of the cases.

Matter is simply being put up for consideration on 18.08.2018.

(Bharat Parashar)

Special Judge, (PC Act),

(CBI-07), DD/PHC

17.07.2018”

12. Investigation on the ECIR as well as the complaint case are still ongoing. It is only in the FIR proceedings that a chargesheet has come to be filed. On 29 November 2018, the Deputy Director came to pass the impugned PAO. It becomes pertinent to note that apart from the allegations which form subject matter of the FIR, the ECIR as well as the complaint, the PAO also alludes to the petitioner having allegedly conspired to manipulate its share prices by issuance of 62,50,000 equity shares on a preferential basis. This is evident from the following recitals as they appear in the PAO:-

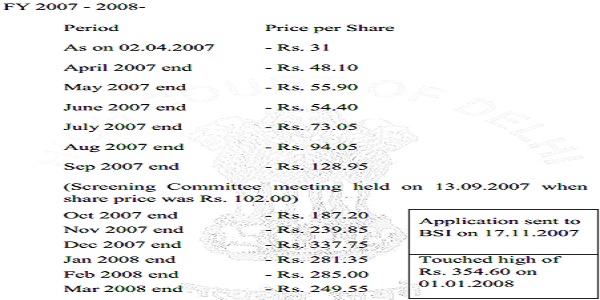

“5.3. That in reply to the department’s query, a letter dated 19.10.2016 was received from SEBI, in response to the department’s letter dated 07/10/2016, forwarding report of BSE Investigation into surge of share price during 2007 2008. This letter inter-alia disclosed that:-

(i) On 05.12.2007 the company informed BSE Ltd. that it is holding EGM for allotment of 62,50,000 equity shares on preferential basis to Mutual Funds, Financial Institutions, FIIS, Body Corporate, NRIs, promoters and their associates;

(ii) Members at the EGM had approved investments by way of issue of warrants convertible into equity shares on preferential basis to Barclays Capital Mauritius Ltd. or its nominees by sale of shares the said company;

(iii) On 19.11.2007 the company informed BSE Ltd. that ministry had allotted a Coal Block in Chhattisgarh for expansion of capacities in the power plant.

(iv) During the period of Examination by BSE Ltd. there were various announcements regarding issue & conversion of warrant shares and also regarding expansion of capacities, establishment and operation of new power plant.

(v) Price of the share increased from Rs.35.75 (open as on January 02, 2007) to Rs.354.60 (high as on January 01, 2008) with average daily volume 1,89,820 shares.‖

13. The PAO ultimately proceeds to record as under: –

“7.5 That all the investors except one also submitted in their respective statements that they were made to believe to the false declaration regarding allocation of coal block to the BSE which led to rise in the share value of M/s Prakash Industries Ltd. and they were made to invest in the equity shares of M/s Prakash Industries Ltd. on preferential basis at a premium of Rs. 180/- per share and further stated that their decision for investment was not appropriate and as the rise in the price could not get sustained and they had to sell the purchased equity shares on a meager value of Rs. 39/- per share. It is pertinent to note that the value of the shares as on 01.04.2007 was also Rs. 31/- per share.

7.6 The issuance of shares at the premium basis having been based on artificial rise in the share value due to false declaration to BSE resulted into undue gain of Rs. 118.75 crores to M/s Prakash Industries Ltd. The gain was actually based upon the commission of scheduled offence as had the party not misrepresented their financial figures during making of an application for allocation of coal block, there would not have been any false declaration to BSE regarding allocation of Fatehpur coal block and further there would not have been gain of Rs. 118.75 crores.

7.7 That M/s Prakash Industries Ltd. as an extension of the criminal activity submitted false declaration to the BSE in order to create hype in the share value. The created hype resulted into increase in their share value and the increased value of the share was further got encashed through issuance of equity shares on preferential basis on premium of Rs. 180/- per share by way of subscription by the five investors. As the whole process was based upon the committed criminal activity and resulted into generation of proceeds of crime to the tune of Rs. 118.75 crores, which was an offence of money laundering u/s 3 of PMLA, 2002. That such proceeds of crime were further utilized by M/s Prakash Industries Ltd. in the continuous expansion of their manufacturing activities.

7.8 The undue gain of Rs. 118.75 crores is proceeds of crime in this case as envisaged vide section 2(1)(u) of the PMLA, 2002 which is reproduced hereunder :

Section 2(1)(u) “Proceeds of crime” means any property derived or obtained directly or indirectly, by any person as a result of criminal activity relating to schedule offence or the value of any such property.

7.9 The proceeds of crime was further used by the party in their continuous investment process and the proceeds of crime are liable to be attached under section 5 of the PMLA, 2002.‖

14. In Para 8, the PAO proceeds to set out the details of the immovable and movable properties which are stated to have been derived and obtained from the commission of scheduled offences and thus constitute the proceeds of crime. It becomes pertinent to highlight here that the allegations relating to the manipulation of share prices and the inducement made for the purposes of allotment of preferential shares do not form part of either the FIR or the ECIR allegations. Since the complaint was not placed on the record, the Court is unable to ascertain whether the subject of preferential allotment of shares forms part of those proceedings.

B. PRELIMINARY OBJECTIONS

15. Before proceeding to notice the rival submissions which were addressed, it would be apposite at this juncture to advert to the preliminary objections which were addressed by Mr. Hossain, learned counsel appearing for the ED.

16. Mr. Hossain urged that the challenge in the present writ petitions pertains to the PAO relating to a coal block which had been allocated to the petitioner. Mr. Hossain also submitted that the cancellation of coal blocks was an issue which directly concerned the Supreme Court in Manohar Lal Sharma vs. The Principal Secretary & Ors10. He specifically referred to the order of 25 July 2014 passed in the aforesaid matter in terms of which the Supreme Court had provided that any prayer for stay or any order impeding the progress of investigation relating to coal block allocations would be liable to be placed before the Special Court only and that no other court could entertain the same. Mr. Hossain contended that in view of the aforesaid directions issued by the Supreme Court, it would not be permissible for this Court to either entertain the present writ petition or take cognizance of the challenge which stands raised. The aforesaid submission was sought to be buttressed further by the subsequent orders made by the Supreme Court in Manohar Lal Sharma and more particularly on 18 July 2014 and 01 September 2015 in that case.

17. It would be relevant to note that by the first order of 25 July 2014 passed in Manohar Lal Sharma, the Supreme Court had provided that all cases pending before different courts pertaining to coal block allocation matters shall stand transferred to the court of the Special Judge. It was the said order that had appointed the Special Judge to deal with all criminal cases arising out of the allocation of coal blocks. By its order of 18 July 2014, the Supreme Court had directed the Chief Justice of this Court to nominate an officer of the Delhi Higher Judicial Service to be posted as the Special Judge to deal with and exclusively try offences pertaining to the allocation of coal block under the IPC, the PC Act and PMLA. The aforesaid order is extracted hereinbelow:-

” 1. We direct the Secretary General of this Court to write to the Registrar General of the High Court of Delhi to take order from the Hon‘ble the Chief Justice, Delhi High Court nominating an officer of Delhi Higher Judicial Service to be posted as Special Judge to deal and exclusively try the offences pertaining to coal block allocation matters under the Indian Penal Code, 1860, Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988, Prevention of Money-Laundering Act, 2002 and other allied offences. The Registrar General, High Court of Delhi shall communicate the decision of the Hon‘ble the Chief Justice on or before 25.7.2014.

2. List this group of matters on 25.7.2014 at 2 P.M.”

Directions for transfer of all pending cases were framed by the Supreme Court in terms of its order of 01 September 2014.

18. Mr. Hossain submitted that the aforesaid orders were considered by a learned Judge of the Court in Girish Kumar Suneja vs. Central Bureau of Investigation11 and in view thereof it had proceeded to dismiss a petition preferred by the accused in the coal block allocation case under Section 482 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973. Mr. Hossain had also referred for the consideration of this Court the judgment rendered by the Supreme Court in Girish Kumar Suneja vs. Central Bureau of Investigation 12 which had affirmed the judgment of the learned Judge of this Court noticed hereinabove.

19. It becomes pertinent to note that in Girish Kumar Suneja, the Supreme Court was called upon to examine a challenge to the restrictive directions which had been framed in Manohar Lal Sharma in terms of which a Special Court came to be constituted for trying all cases pertaining to coal block allocations and the directions divested all other courts of the authority to deal with challenges arising therefrom. The restrictions so imposed and which also constricted the right of a High Court to exercise powers conferred by Articles 226 and 227 of the Constitution or for that matter its revisional and inherent powers were ultimately affirmed. While upholding the aforesaid restrictions, the Supreme Court in Girish Kumar Suneja observed as follows:-

“43. In our opinion, it is not as if one single case has been taken up for allegedly discriminatory treatment out of an entire gamut of cases. All the cases relating to the allocation of coal blocks have been compartmentalised and are required to be treated and dealt with in the same manner. The Coal Block Allocation cases form one identifiable category of cases that are distinct from other cases since they have had a massive impact on public interest and there have been large-scale illegalities associated with the allocation of coal blocks. It is therefore necessary to treat these cases differentially since they form a unique identifiable category. The treatment of these cases is certainly not arbitrary—on the contrary, the classification is in public interest and for the public good with a view to bring persons who have allegedly committed corrupt activities, within the rule of law. It is hence not possible to accept the submission that by treating the entire batch of Coal Block Allocation cases in a particular manner different from the usual cases that flood the courts, there is a violation of Article 14 of the Constitution.

45. Insofar as the present appeals are concerned, the cases fall in a class apart, arising as they do out of the illegal and unlawful allocation of coal blocks. It is only in respect of these cases that this Court monitored the investigations and it is only in respect of these cases that the order was passed by this Court on 25-7-2014 [Manohar Lal Sharma v. Union of India, (2015) 13 SCC 35 : (2015) 13 SCC 37 : (2016) 1 SCC (Cri) 418 : (2016) 1 SCC (Cri) 419] . The cases are concerned with large-scale corruption that polluted the allocation of coal blocks and they form a clear and distinct class that need to be treated in a manner different from the cases that our justice-delivery system usually deals with. The classification being identifiable and clear, we do not see any violation of Article 14 of the Constitution.

57. There is obviously some misconception in this regard as far as the appellants are concerned. This Court is not in any manner monitoring the progress of the trial in the Coal Block Allocation cases nor is it supervising the trial. Conducting the trial is entirely the business of the learned Special Judge. Para 10 of the order only results in the removal of any impediment in the progress of the trial. To ensure that the trial is concluded at the earliest not only in the interest of the accused persons but also in public interest, any application intended to stay or impede the trial will be subject to orders of this Court. This out of the ordinary step has been taken given the serious nature of allegations made against those believed to be involved in the illegal allocation of coal blocks and in the interest of the accused as well as in larger public interest. As mentioned above, there is a need for maintaining a balance between the rights of an accused and the rights of an individual victim and society.

59. The submission that para 10 of the order passed by this Court fetters the discretion of the High Court in granting a stay of proceedings proceeds on the assumption that the High Court has an unfettered discretion to stay a trial. This is simply not so—the stay of a trial is a rather an extraordinary step and cannot be given for the asking.‖

20. This Court, however, finds itself unable to accede to the preliminary objection which is raised in this respect for the following reasons. As would be evident from the various orders which were passed in Manohar Lal Sharma, the Special Court which came to be constituted was so identified solely to deal with and exclusively try offences emanating from coal block allocations and for the trial of offences that may have been alleged to have been committed either under the IPC, the PC Act and the Act with which we are concerned. The direction for transfer of pending cases also clearly appears to be confined to criminal matters arising out of coal block allocations. The Girish Kumar Suneja judgment of this Court was also dealing with a petition under section 482 of the CrPC and which had challenged an order passed by the Special Judge directing framing of charges.

21. It is thus manifest that the directions in Manohar Lal Sharma stood confined to criminal proceedings instituted in relation to coal block allocations. Those directions cannot possibly be construed or interpreted as extending to PAO‘s that may be made under the Act. The Court also bears in mind the fact that the Special Judge so constituted to try criminal cases and offences would clearly lack the authority to either deal with or rule upon the validity of PAOs that may be made. If the submission addressed by and on behalf of the ED in this regard were be accepted, it would also amount to short-circuiting the adjudicatory mechanism with respect to attachment orders as structured and placed in terms of the provision of the Act. That clearly neither appears to be the intent of the orders passed in Manohar Lal Sharma nor can those directions be possibly construed as denuding this Court of the jurisdiction to entertain a challenge relating to a PAO and the exercise of power by the ED under Section 5 of the Act.

22. Mr. Hossain while referring to the orders which were passed by the Supreme Court in Manohar Lal Sharma had also placed reliance upon the decision rendered by a Division Bench of the Bombay High Court in Ashok Sunderlal Daga vs. Union of India & Ors.13 to contend that a challenge to PAO‘s would also amount to delaying or impeding the investigation or trial of coal block allocation cases. It becomes pertinent to note that in Ashok Sunderlal Daga, the Bombay High Court was principally dealing with a challenge to the ECIR which had come to be registered. While dealing with the aforesaid challenge, it was also noticed that orders of attachment under Section 8(5) of the PMLA had come to be passed. It was, however, pertinently noted that the aforesaid attachment orders formed subject matter of challenge before the concerned appellate authority. It was in that backdrop that the Bombay High Court observed as follows:-

“24. These observations of Hon’ble Supreme Court therefore, clearly show that all matters which question any such investigation or offence pertaining to coal block allocation and related matters under Penal Code, 1860, Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988, Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002 and other allied offences must be looked into by the Hon’ble Supreme Court.

25. Facts of case at hand reveal that provisional attachment order and complaint filed by the Assistant Director, Directorate of Enforcement beyond doubt show the nexus of proceeds of crime with coal block allotment. The contention of enforcement department that it got knowledge of proceeds of crime only through investigation into coal block allotment, cannot be disputed at this stage. The reply on preliminary objection to the maintainability of the petition filed by respondents, shows that on the basis of FIR dated 07.08.2014, CBI, New Delhi registered a case under Section 120B and 420 of Penal Code, 1860 and a charge sheet came to be filed on 31.12.2015 before the Additional Sessions Judge and CBI Special Court, New Delhi against petitioner and his company. That FIR and charge sheet was forwarded by CBI to respondents as case involved economic offence and offence of money laundering. Respondents claim that it is the only organization empowered to investigate offence of money laundering. They submit that in case in Criminal Writ Petition No. 697/2017, the proceeds of crime relating to scheduled offence, were noticed and the provisional attachment order was made on 12.09.2016 attaching properties worth Rs. 1.67 Crores. Paragraph no. 9 thereof discloses that the adjudicating authority has on 31.01.2017 confirmed the attachment of property.

26. Accused persons have filed an appeal on 24.03.2017 before the Appellate Tribunal under 2002 Act at New Delhi and it is pending before that Tribunal.

27. These facts sufficiently reveal, at least at this stage and before this Court in its jurisdiction under Article 226, that the link between the pending prosecution for coal block allotment and the attachment order which gave rise to present writ-petitions cannot be ignored.

30. In the light of this discussion, we uphold the preliminary objection raised by learned A.S.G.I. We declare that Criminal Writ Petitions filed before this Court are not maintainable. We also clarify that the observations made by us supra, are in the light of arguments advanced and only to the extent necessary to evaluate the same. The same will not have any bearing or influence on the pending appeal before the Appellate Authority under 2002 Act, or pending prosecutions before the Special Court at New Delhi.”

23. This Court is of the considered view that a challenge to a PAO on merits cannot possibly be assailed before the Special Judge who has come to be appointed pursuant to the orders of the Supreme Court in Manohar Lal Sharma. The Special Judge and the court which consequently came to be constituted pursuant to the directions of the Supreme Court is essentially concerned with the trial of offences relating to and arising out of allocation of coal blocks. On a consideration of the various orders passed by the Supreme Court in Manohar Lal Sharma, it is manifest that they were essentially intended to centralize the trial of all offences arising out of allocation of coal blocks and in any case cannot possibly be read as conferring jurisdiction on the Special Judge to deal with the validity of attachment orders that may be passed by the competent authorities under the Act. If the submission of Mr. Hossain were to be accepted, it would essentially amount to recognizing a power inhering in the Special Judge to not only don the robes of the Adjudicating Authority under Section 8 but to also deprive the appellate forums of the jurisdiction to decide appeals against the orders that may ultimately come to be passed under Section 8 of the Act. The objections thus raised on this score stand negatived.

24. Mr. Hossain had also argued that when the writ petition was initially filed, the Court had entertained the same since the CBI had come to file a closure report before the Special Court. It was submitted that subsequent thereto, a supplementary chargesheet came to be filed by the CBI on 17 November 2021. In view of the aforesaid, it was contended by Mr. Hossain that the jurisdictional ground on which the writ petition had been entertained clearly did not survive and therefore the petitioner must be relegated to the alternative statutory remedy of raising all objections before the Adjudicating Authority.

25. The Court notes in this regard that while it may be true that the CBI had subsequently and during the pendency of the present writ petitions submitted a chargesheet, the petitioners have raised substantial jurisdictional challenges to the PAO. The petitioners have asserted that the PAO is founded on allegations and facts which neither constitute a part of the FIR allegations nor for that matter the ECIR and the complaint. According to the petitioners, ED cannot possibly be recognized as having been conferred the authority to investigate the commission of a scheduled offence. These as well as the other challenges which shall be noticed hereinafter clearly constitute substantive grounds justifying the retention of the writ petitions and for a decision being rendered by this Court under Article 226 of the Constitution.

C. PETITIONER‟S ARGUMENTS

26. Appearing for the petitioners, Mr. Chawla, learned counsel, addressed the following submissions. Learned counsel submitted that the PAO impugned in the present writ petitions is wholly illegal since it is based on various factual allegations and assertions which do not form part of either the FIR, the ECIR or for that matter the complaint that subsequently came to be lodged. According to learned counsel, the foundation of the PAO goes far beyond the allegations relating to the predicate offence as embodied in the FIR and the ultimate chargesheet which was submitted by the CBI. It was contended that a reading of the PAO would establish that it is based on an allegation that the petitioner raised a sum of Rs. 118 crores by issuing preferential shares at an exorbitant premium and that this amount would constitute proceeds of crime. It was submitted by Mr. Chawla that the aforesaid facts neither form part of the chargesheet which was submitted by the CBI nor do those allegations form part of the ECIR or the criminal complaint which came to be lodged by the ED in exercise of powers conferred by Section 45 of the Act.

27. Mr. Chawla submitted that the power to provisionally attach properties under the PMLA can only be exercised if there be substantiation of an offence as contemplated under Section 3 being evidenced. It was submitted that the definition of “proceeds of crime” as contained in Section 2(1)(u) of the PMLA links the same to criminal activity relating to a scheduled offence. According to Mr. Chawla, the issue of whether the petitioner had committed a crime in the course of allocation of preferential shares does not form part of the criminal investigation which had been initiated against it in terms of the FIR and ECIR. In view of the above, Mr. Chawla would contend that the respondent could not have provisionally attached properties based on allegations which were wholly foreign to the reports which pertained to the predicate offence.

28. Mr. Chawla contended that PMLA does not empower the ED to either investigate or register reports in respect of a scheduled offence. Learned counsel submitted that the respondents are conferred jurisdiction only to try and investigate an offence of money laundering. That power, according to Mr. Chawla, cannot possibly be read as extending to the ED being empowered to independently investigate scheduled offences or provisionally attach properties based upon what it may perceive as activities amounting to the commission of a scheduled offence. The substance of the contention was that in the absence of any criminal proceedings having been registered or lodged relating to the allocation of preferential shares, the PAO insofar as it rests upon those allegations, is clearly rendered unsustainable.

29. Mr. Chawla then submitted that this Court has already ruled against the respondent insofar as an allocation of a coal block constituting proceeds of crime is concerned. Reference in this regard was made to the judgment rendered by the Court in Prakash Industries Ltd. And Another vs. Directorate of Enforcement14 [Prakash Industries-I]. It was further contended that the challenge in the present proceedings in any case is liable to succeed in view of the judgment rendered by the Court in Himachal EMTA Power Limited vs. Union of India and Others15. Mr. Chawla submitted that undisputedly although the Fatehpur Coal Block had been allocated to the petitioner, it was never utilised and no coal as such was extracted pursuant thereto. It was in the aforesaid backdrop that Mr. Chawla commended Himachal EMTA for the consideration of the Court.

29. In Himachal EMTA, the Court was dealing with a challenge to a PAO which came to be made by the ED attaching investments made by the petitioners in a joint venture company as well as certain amounts which were held in Fixed Deposit. The Court found that inarguably no mining activity had been undertaken by the petitioner there pursuant to the allocation having been made in its favor. Dealing with the issue of whether the investments made by the petitioner could be held to constitute proceeds of crime, the Court held as follows:-

“18. A plain reading of the impugned order indicates that there is no material whatsoever on the basis of which the ED could have possibly concluded that the investments made by HEPL were derived or obtained‘ as a result of any criminal activity relating to a scheduled offence. In the impugned order, the ED has elaborately discussed the allegation made against HEPL. It is also recorded that at the time of filing of the application for allocation of coal block, the capital of HEPL was Rs. 5 lakhs which had swelled upto Rs. 7.91 crores after filing application for a coal block. The investment made by joint venture constituents of HEPL, namely, Himachal Pradesh Power Corporation Ltd. and EMTA, were further invested by HEPL; including in subscribing to the shares of CGL. The same cannot by any stretch be held to be proceeds of crime. The ED has, essentially sought to attach the investments made in HEPL on the allegation that the same have been used in commission of a scheduled offence. This is apparent from paragraphs 7 and 16 of the impugned order which are set out below:

“7. AND WHEREAS, the investment of Rs. 7.91,00,000/- was made after filing for allocation of Coal Block, and the same has been used in commission of scheduled offence. i.e. the allocation of coal block by fraudulent means and to further obtain mining lease on the basis of said allocation. Further, there is a balance of Rs. 1,33,700/- lying in the bank accounts as mentioned at Para 5(xiv) and the fixed deposit No. 015340100288/8 dated 4.7.2017 amounting to Rs. 11,86,710/-.

***

16. AND WHEREAS, the following amounts have been used in the commission of scheduled offence and are proceeds crime in terms of Section 2 (u) and 2 (v) of PMLA, 2002:—

|

S. No. |

Amount in Rs. | Remarks |

| 1. | 2,45,00,000 | Investment in M/s GCL By M/s HEPL and lying in Corporation Bank, Bhowanipur Branch, Kolkata A/c No. 510101003473693 of M/s GCL. |

| 2. | 11,86,710 | Lying as fixed deposits No. 015340100288/8 dated 04.07.2017 |

| 3. | 1,26,540 | Lying in A/c No. 0153201100424 |

| 4. | 7,160 | Lying in A/c No. 0153201002578 |

| Total | 2,58,20,410 |

19. The said assumption that any amount used in commission of a scheduled offence would fall within the expression ―proceeds of crime” as defined under Section 2(1)(u) of the PML Act is fundamentally flawed. In the present case, the allegation against HEPL is that it had obtained allocation of coal block on the basis of misrepresentation. However, it is not disputed that mining of the coal from the block had not commenced, therefore, HEPL did not derive or obtain any benefit from the coal block. The ED has also not indicated any reason, which could lead one to believe that HEPL had derived any other benefit from the allocation of the coal block in question.”

31. Mr. Chawla would submit that in Himachal EMTA too, the allegation was that on the strength of the coal block allocation, investments came to be made. While dealing with the aforesaid challenge, the Court had held that the procedure adopted by the ED was fundamentally flawed. It was noted that while it had been alleged that the coal block had been obtained by way of misrepresentation, no mining activity pursuant thereto was undertaken and thus it could not be said that the petitioner had derived or obtained any benefit from the said allocation.

32. Mr. Chawla then submitted that the premise on which the respondent has proceeded to doubt the allocation of preferential shares is also clearly misconceived since the petitioners had to statutorily make a disclosure with respect to the coal block allocation bearing in mind the provisions contained in the Securities and Exchange Board of India (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations, 201516. It was further contended that the premium of Rs. 180/- per share was also calculated strictly in accordance with the SEBI guidelines for preferential issues. It was submitted that the petitioner could not have been faulted for having convened any Extraordinary Meeting of its body of shareholders to approve the issuance of preferential shares since that was a mandatory requirement under Section 81 of the Companies Act, 195617.

33. It was further asserted that the impugned action of the respondent is in clear contravention of Section 8(3) of the Act. It was contended that the record would establish that the complaint under Section 45 came to be lodged on 17 July 2018 and thus evidently prior to the passing of the impugned order on 29 November 2018. It was submitted that as would be evident from a perusal of the order passed by the Special Judge on 17 July 2018 itself, the complaint came to be lodged late in the evening on the said date and only to circumvent the rigors of Section 8. According to learned counsel, the order of the Special Judge itself records and bears testimony to the above.

34. The challenge based on Section 8(3) proceeds on the following lines. According to Mr. Chawla, Section 8(3)(a) as it stood at the relevant time contemplated the Adjudicating Authority confirming an attachment and which was to not exceed 90 days. This position prevailed prior to Section 8(3)(a) being amended in terms of the Finance Act, 2018 which came into force on 29 March 2018. Mr. Chawla would submit that as per Section 5, the validity of a PAO could not have exceeded 180 days. That order, in terms of Section 8(3)(a) as it stood prior to its amendment in 2018, would have to be necessarily confirmed within a period of 90 days. The cumulative period of 270 days when computed from the date of the passing of the PAO would thus expire on 26 August 2019. It was submitted that even if the amended Section 8(3)(a) were to be assumed to apply, the maximum period for which the PAO could have operated would be 180 days + 365 days. Mr. Chawla submitted that viewed in that light, the provisional attachment could have continued only for a period of 545 days [180 + 365 days] and thus expire on 27 May 2022. Mr. Chawla essentially submitted that the filing of the complaint was clearly mala fide and clearly amounts to a fraud upon the statute. It was contented that the complaint came to be preferred and instituted at a time when a final report recommending closure had already been submitted by the CBI and even prior to the submission of a chargesheet which admittedly came to be filed before the competent court on 17 November 2021. According to learned counsel, the aforesaid facts would clearly establish that the action of the ED was wholly arbitrary and illegal.

35. Mr. Chawla submitted that the action of the respondents in continuing to keep the various properties of the petitioner provisionally attached is also manifestly unjust since they have failed to conclude investigation either with respect to the ECIR or the complaint lodged under Section 45. Taking the Court through the order sheet relating to the aforesaid proceedings, it was pointed out that it would be evident that the proceedings are being continually adjourned since the respondent has failed to conclude investigation. It is in the aforesaid backdrop that it was asserted that the action of the respondents fairly amounts to a fraud upon the statute itself.

D. E.D.’s CONTENTIONS

36. Mr. Hossain, learned counsel appearing for the ED, has urged the following submissions for the consideration of the Court. It was firstly submitted that the chargesheet filed by the CBI establishes the nine instances of misrepresentation practiced by the petitioner leading up to the allocation of the coal block. He further highlighted the fact that one of those misrepresentations was with respect to the net worth of the petitioner being Rs.532 crores when, in fact and as would be evident from Para 16.34 of the chargesheet submitted by CBI, the said calculation was found to be patently incorrect and misleading. In view of the aforesaid facts, Mr. Hossain contended that the respondents would have the requisite jurisdiction to attach the proceeds of crime and which would extend to any property derived or obtained directly from the commission of the said scheduled offence. Mr. Hossain laid emphasis on the usage of the phrase “relating to” in Section 2(1)(u) to submit that the expressions “relating to” or “relatable” are clearly aimed at expanding the scope of the definition of “proceeds of crime” and cannot be conferred a restrictive or narrow meaning. Mr. Hossain in support of the aforesaid contention sought to draw sustenance from the following observations as entered by the Supreme Court in Doypack Systems (P) Ltd. vs. Union of India18:-

“50. The expression “in relation to” (so also “pertaining to”), is a very broad expression which presupposes another subject matter. These are words of comprehensiveness which might have both a direct significance as well as an indirect significance depending on the context, see State Wakf Board v. Abdul Azeez [AIR 1968 Mad 79, 81, paras 8 and 10] , following and approving Nita Charan Bagchi v. Suresh Chandra Paul [66 Cal WN 767] , Shyam Lal v. M. Shyamlal [AIR 1933 All 649] and 76 Corpus Juris Secundum 621. Assuming that the investments in shares and in lands do not form part of the undertakings but are different subject matters, even then these would be brought within the purview of the vesting by reason of the above expressions. In this connection reference may be made to 76 Corpus Juris Secundum at pages 620 and 621 where it is stated that the term “relate” is also defined as meaning to bring into association or connection with. It has been clearly mentioned that “relating to” has been held to be equivalent to or synonymous with as to “concerning with” and “pertaining to”. The expression “pertaining to” is an expression of expansion and not of contraction.”

37. It was his contention that paragraph 7.6 of the PAO would clearly establish that illegal gains were obtained and derived by the petitioner as a result of criminal activity and more particularly upon commission of the offence of criminal conspiracy to cheat. Mr. Hossain submitted that Section 120B of the IPC is an independent and standalone offence and must be understood and construed as such. It was his submission that the acts of the petitioner relating to the issuance of preferential shares and allotment thereof at a premium had a direct nexus and relation to the misrepresentation made in their original application of 12 January 2007 for allocation of the coal block. It was submitted that from inception, the petitioner had sought to mislead and misrepresent the Union Government in order to obtain the allocation and that all steps taken in connection therewith were in continuation of the intent to cheat and derive undue benefits. It was contended that the chargesheet submitted by CBI reveals that apart from the misrepresentation made on several accounts, the petitioner had also deliberately submitted a Techno-Economic Feasibility Report instead of submitting a Project Report as required in terms of the advertisement. Mr. Hossain pointed out that the aforesaid TEFR itself related to the expansion of an integrated steel plant at Chamba and Korba and contained no mention of the setting up of a 500 MW power plant for which the allocation itself had been sought. These facts, according to Mr. Hossain, are evidenced from a reading of paras 16.3, 16.4 and 16.22 of the CBI chargesheet. The relevant parts of the chargesheet are extracted hereinbelow:-

16.3 During investigation the allegations of the FIR were not substantiated and it was found that M/s Prakash Industries was having sufficient net worth as per the criteria of Ministry of Power for allocation of the coal block for the end use capacity for which the coal block was allocated to it. However, some procedural error was noticed on the part of the officers of Ministry of Coal in wrong calculation of the coal share of M/s Prakash Industries Ltd in Fatehpur Coal Block. Therefore, an SPs report recommending Such Action as deemed fit against Shri K C Samaria, the then Director, Shri VS Rana, the then Under Secretary and Shri R N Singh the then Section Officer was sent to the Ministry of Coal by CBI vide letter dated 23/02/2015.

1.6.4 Thereafter a Report u/s 173(2) of Cr.PC, recommending closure of the case was filed in this Hon’ble Court on 20/11/2014. However, during hearings on the said closure report Sh. Prakash Javadekar, Sh. Hansh Raj Ahir and Shri Bhupender Yadav, whose complaint had been forwarded by CVC to CBI for enquiry, filed protest petition through their advocates and opposed the closure of the case. The issues raised in the protest petition as well as certain new aspects which subsequently came to light were further investigated by CBI under Intimation to the Hon’ble Court.

6.22 Investigation has further revealed that M/s Prakash Industries Ltd in its application form dated 12.01.2007 for Fatehpur coal block in Chhattisgarh had misrepresented that Detailed Project Report (DPR) for the end use project had been prepared and the same was appraised by the Financial Institution. But Instead of submitting “Project Report” as mentioned in the advertisement, it submitted a Techno-Economic Feasibility report (TEFR) with respect to expansion of Integrated Steel Plant at Champa and Korba and setting up of Integrated Steel Plant for Jagdalpur, Chhattisgarh under signature of Sh. AK. Chaturvedi, President (Corporate Affairs) as its Authorised Signatory. In this Techno-Economic Feasibility report (TEFR), there is no mention about setting up of 500 MW captive power plant at Village Champa, Distt. Janjgir, Chhattisgarh. The said TEFR inter alia belonged to a 375 MW captive Thermal Power Plant (Fluidized Bed Boller) proposed to be set up by the company at Distt. Korba, Chhattisgarh, whereas the location of the EUP i.e. Captive Power Plant for which the coal block had been applied by the company was District Janjgir Champa, Chhattisgarh. As such it was the TEFR for a different project. However, in the corresponding column No. 21 (1) and (ii) of the application form wherein it was asked whether DPR has been prepared and if yes, whether appraised by FI (Financial Institutions), M/s Prakash Industries Ltd mentioned “Yes” In both columns.”

38. It was also pointed out that the chargesheet submitted by CBI ultimately and clearly establishes that not only did the petitioner misrepresent the net worth of the company, a larger conspiracy was hatched from the inception to induce the Union Government to allot the coal block. It was submitted that the petitioner had in furtherance of the aforesaid design acted along with various other individuals including those who were posted at that time in the Ministry of Coal. It was submitted that not only had the petitioner made a series of misrepresentations with regard to its net worth, it had also deceived and misled the Union Government with respect to the total land available for the project, civil constructions, orders for plant and machinery and environmental clearance. It was pointed out that the petitioner had falsely alleged that it was in possession of 505.89 acres of land when in fact an integrated steel plant had already been set up thereon and, therefore, the entire parcel of land was not available for establishment of a 500 MW captive power plant. Mr. Hossain argued that the misinformation with respect to arrangements relating to availability of water as well as environmental clearance are apparent from the facts recorded by the CBI in paras 16.48 and 16.63 of the chargesheet. It was further contended that the statement made on behalf of the petitioner that it had already invested Rs.1150 crores and that the balance amount would be arranged through equity and borrowings from banks and financial institutions was also ultimately found to be false. The misrepresentations, according to Mr. Hossain, were taken notice and cognisance of by the Special Judge in the order of 10 February 2022. According to Mr. Hossain, the aforesaid facts would clearly justify the provisional attachment as affected by the ED.

39. Turning then to the proceeds obtained by the petitioner from allotment of preferential shares, Mr. Hossain submitted that they would clearly constitute illegal gains relatable to a scheduled offence of criminal conspiracy to cheat. It was contended that a false declaration was made by the petitioner to the BSE on 17 November 2007 asserting that the coal block in question had been allotted in its favour when in fact the allocation came to be made only on 06 February 2008. Mr. Hossain referred to the conclusions and reasons which have been recorded in paragraphs 7.5 to 7.9 of the PAO insofar as this aspect is concerned.

40. It was submitted that the financial gains which were acquired by the petitioner from the allotment of preferential shares would clearly amount to illegal gains obtained and derived by the utilisation of the coal block allocation and would thus satisfy the tests of proceeds of crime as were enunciated by the Court in Prakash Industries-1. In any case according to Mr. Hossain, the gains attained from the allotment of preferential shares were unmistakably based upon the commission of a scheduled offence. This since had the petitioner not misrepresented facts pertaining to the net worth of the company during the course of submission of the application for allocation of the coal block, they would have neither been eligible to be allotted the same nor would they have been in a position to make an illegal profit of Rs.118.75 crores by the allotment of preferential shares after ensuring that the share price of the petitioner had astronomically risen.

41. Mr. Hossain then, while controverting the submissions addressed at the behest of the petitioner and relating to an asserted violation of Section 8(3)(a) of the Act submitted that the writ petition is bereft of any pleadings or prayers in respect of the contention addressed on the anvil of Section 8(3)(a). Mr. Hossain submitted that the contention that the complaint under Section 45 was filed unfairly and was only aimed at stopping the march of limitation as enshrined in Section 8(3)(a) would essentially amount to a challenge to the investigation itself. It was submitted that merely because further investigation on the said complaint is ongoing, that cannot constitute a ground which may be sufficient in law for this Court to hold that the original complaint itself has been vitiated. In any case according to Mr. Hossain, there can be no challenge to the prosecution complaint in the absence of any reliefs having been claimed or sought in the writ petition in this respect.

42. Mr. Hossain further submitted that the power of the ED to undertake further investigation in terms of Section 44(2) of the PMLA has been recognised as a wholesome provision by the Supreme Court in Vijay Madanlal Choudhary & Ors. vs. Union of India & Ors.19 and in acknowledgment of the statutory position of it being empowered to file subsequent complaints. According to learned counsel, all additional or subsequent complaints would be deemed to be a part of the original complaint that had been lodged. Mr. Hossain further submitted that merely because in the perception of the petitioner the investigation by ED remains either incomplete, ongoing or cognizance on the chargesheet having not been taken by the court, would not deprive it of the right to proceed under the Act. It was submitted that Section 8(3)(a) unambiguously stipulates and prescribes that a PAO will continue to remain in operation till proceedings are pending in any court. In view of the above, it was submitted that it cannot possibly be said that the attachment was illegal. It was further urged by Mr. Hossain that the interim order of the Supreme Court which has merely stayed further proceedings before the Special Judge would not efface or wipe out the factum of a scheduled offence having been committed or proceeds of crime having been derived and obtained.

E. UNDERPINNINGS OF THE PAO

43. Having noted the rival contentions which have been addressed and before proceeding further, the Court is of the considered opinion that it would be relevant to firstly advert to the nature of the allegations which stood leveled in the FIR and chargesheet filed by the CBI, the ECIR registered at the behest of the ED and the complaint referable to Section 45. As was noticed in the earlier parts of this decision, the FIR came to be registered by CBI on 26 March 2014 alleging the commission of offences referable to Sections 120B read with Section 420 IPC as well as Sections 13(2) read with Section 13(1)(d) of the PC Act. The FIR arraigned the Promoters/Directors of the petitioner, members of the 35th Screening Committee constituted by the Ministry of Coal, unknown officials of that Ministry and other unknown persons. The FIR firstly refers to the policy of captive coal mining by private entities engaged in the power, steel and cement sectors of the national economy. It takes notes of the constitution of a Screening Committee which had been constituted by the Ministry for drawing recommendations for allocation of the shortlisted coal blocks. It also alludes to the Guidelines framed by the Ministry of Coal and which were to govern the framing of recommendations by the Screening Committee. The FIR proceeds to record that on 13 November 2006, an advertisement was published for allotment of 35 coal blocks for captive mining. Out of the aforesaid, 15 blocks were reserved for power generation projects while the remaining were reserved for the steel and cement sectors.

44. The petitioner is stated to have submitted an application for allotment of a coal block for setting up a power plant of 650 MW at village Champa, District Janjgir in the State of Chhattisgarh. The aforesaid application is stated to be dated 12 January 2007. The said application appears to have been examined by the Ministry of Power as well as the Central Electricity Authority. According to the allegations leveled, the net worth of an applicant company was required to be 0.50 Crore per MW of the maximum capacity laid down for Ultra Mega Power Plants. The project capacity was pegged at a minimum of 500 MW. According to the FIR allegations, on a screening of a total of 187 applications which were received, 115 stood prequalified. On a further shortlisting, 44 applications were identified. The petitioner did not meet the criteria as adopted and was not included in the list of these 44 applications. The matter is thereafter stated to have been further examined by the Ministry of Power which identified and recommended 27 entities according to specified blocks to the Screening Committee for allocation. The name of the petitioner did not appear even in this list of 27 shortlisted applicants.

45. The FIR then goes on to assert that the petitioners in their application form had declared their net worth as on 31 March 2006 to be Rs.532 crore. However, and it is so alleged in the FIR, on due inquiry and investigation it has been found that the net worth of the petitioner as on that date was actually Rs. (-) 144.16 crores. The FIR then proceeds to allege that despite these facts existing on the record, the Screening Committee proceeded to rest its recommendation in favour of the petitioner solely on the self-declarations made by it and failed to even consider the same being examined independently by financial experts. Based on the recommendations of the Screening Committee, the Fatehpur Coal Block ultimately came to be allocated to the petitioner formally on 06 February 2008.

46. The record would further bear out that initially CBI submitted a final report recommending closure in terms of Section 173 of the Criminal Procedure Code. While the aforesaid final report was not formally accepted since protest objections came to be filed in the meanwhile by the complainants, CBI ultimately came to submit a chargesheet on 17 November 2021. The chargesheet while dealing with the proceedings which were taken before the Screening Committee and the Ministry of Coal lays the following allegations: –

“16.13 Investigation has further revealed that regarding processing of application forms in the Ministry of Coal following instructions were mentioned in the advertisement under the heading ―Processing of Application‖:-

“The applications received in the Ministry of Coal in five copies, after being checked for eligibility and completeness, would be sent to the Administrative Ministry/State Government concerned for their evaluation and recommendations. After receipt of the recommendations of the Administrative Ministry/State Government concerned the Screening Committee would consider the applications and make its recommendations. Based on the recommendations of Screening Committee, Ministry of Coal will determine the allotment.

16.14 Subsequently, in the Ministry of Coal, It was decided that all the companies who had applied for coal blocks for Power sector would be called for giving presentation in respect of their End Use Project (EUP) and will also submit a Feed Back form mentioning the latest status of their EUP.

16.15 Investigation has further revealed that Fatehpur Coal block was a non coking coal block located in the state of Chhattisgarh and was earmarked for power sector. Total 69 applicant companies Including M/s Prakash Industries Ltd. had submitted their applications for Fatehpur coal block. M/s Prakash Industries Ltd had applied for its existing 65 MW + proposed 500 MW Thermal Power Plant to be setup at Village Champa, Distt. Janjgir, Chhattisgarh. Application of M/s Prakash industries ltd was submitted on 12.01.2007 under Signature of Sh. AK Chaturvedi, President (Corporate Affairs) who had been authorized for the same by Sh; G. L Mohta, the then whole time Director of the Company vide 6PA dated 20th April, 2006.

16.16 Investigation has further revealed that M/s Prakash Pipes and Industries Ltd was Incorporated In the year 1980 and was registered with RoC, Delhi & Haryana on 31.07.1980 vide Registration Mo. 10724 of 1980-81. Later on, its name was changed to M/s Prakash Industries Ltd. vide RoC approval fetter No, 21/H-10724/20166 dated 01.11.1990.

16.17 Investigation has further revealed that in the Ministry of Coal applications received in response to the advertisement for allocation of coal blocks were not checked for their eligibility and completeness as was mentioned In the advertisement and were sent to the Administrative Ministry / State Government concerned for their evaluation and recommendations without the same. Sh H, C. Gupta, the then Secretary, and Sh, K. S. Kropha, the then Joint Secretary, Ministry of Coal were well aware that the applications were being sent to the state Govt. and administrative Ministry without being checked for eligibility and completeness.

16.18 Investigation has further revealed that vide letter Mo. 13016/55/2006-CA-I dated 19/28.02.2007, Ministry of coal had sent the applications received for Fatehpur Coal Block to the Govt. of Chhattisgarh.

16.19 Sh. Debasish Das, Special Secretary, Govt. of Chhattisgarh, Energy Department vide letter No. 1293/2/13/ED/Coal BI, Allot./2007 Raipur Dated 18.06.2007 conveyed the recommendation of the State Govt. of Chhattisgarh for non coking coal blocks. M/s Prakash Industries Ltd. was recommended for allocation of a coal block for 715 MW captive power plant capacity.

16.20 investigation has further revealed that Ministry of Coal vide letter No. 13016/65/2005-CA-I (Part) dated 17.04,2007 under the signature of Sh. V. S. Rana, Under Secretary had forwarded the applications received for Power sector to the Ministry of Power for their comments with the approval of Sh. K. C. Samria, Py. Secretary, Ministry of Coal.

16.21 Vide letter No. Nil dated 30.07.2007, Secretary, Ministry of Power forwarded its recommendation to the Secretary, Ministry of Coal, Ministry of Power had not recommended allocation of any coal block to M/s Prakash Industries Ltd.

16.22 Investigation has further revealed that M/s Prakash Industries ltd In its application form dated 12.01.2007 for Fatehpur coal block in Chhattisgarh had misrepresented that Detailed Project Report (DPR) for the end use project had been prepared and the same was appraised by the Financial Institution. But instead of submitting “Project Report” as mentioned in the advertisement, it submitted a Techno-Economic Feasibility report (TEFR) with respect to expansion of Integrated Steel Plant at Champa and Korba and setting up of Integrated Steel Plant for Jagdalpur, Chhattisgarh under signature of Sh. A.K. Chaturvedi, President (Corporate Affairs) as its Authorised Signatory. In this Techno-Economic Feasibility report (TEFR), there is no mention about setting up of 500 MW captive power plant at Village Champa, Distt. Janjgir, Chhattlsgarh. The said TEFR inter alia belonged to a 375 MW captive Thermal Power Plant (Fiuidized Bed Boiler) proposed to be set up by the company at Distt. Korba, Chhattisgarh, whereas the location of the EUP i.e. Captive Power Plant for which the coal block had been applied by the company was District Janjgir Champa, Chhattisgarh. As such it was the TEFR for a different project. However, in the corresponding column No. 21 (i) and (ii) of She application form wherein it was asked whether DPR has been prepared and if yes, whether appraised by FI (Financial Institutions), M/s Prakash Industries Ltd mentioned “Yes” in both columns.

16.23 Investigation has further revealed that “Project Report” was one: of the essential documents to be submitted along with the application form as mentioned in the advertisement Issued by the Ministry of Coal, for assessment of the applicant company by Administrative Ministry for making suitable recommendation to the Screening Committee.

16.24 Whereas, M/s. Prakash Industries Ltd submitted an Irrelevant TEFR, which had no details of the proposed 500 MW power plant at Village Champa, Distt. Janjgir, Chhattisgarh, As per requirement of the advertisement issued by the Ministry of Coal, if Project Report in respect of End Use Plant was not submitted along with the application, the application form would have been treated as incomplete and It should have been rejected at the initial stage.

16.25 Investigation has further revealed that Sh, H.C. Gupta, the then Secretary, Ministry of Coal and Sh. K.S. Kropha, the then Joint Secretary of Ministry of Coal did not ensure the scrutiny of the application forms received from the applicant companies for its eligibility and completeness and proceeded ahead to consider the incomplete applications which should have been rejected at the initial stage.

16.26 In the application form, M/s. Prakash Industries Ltd had made the following claims regarding Its preparedness for setting up of its EUP I.e. 500 MW Captive power plant at Champa, Janjgir, Chhattisgarh.

|

S. No |

Heads | Claim |

| 1 | Net worth as on 31.03.2006 | 532.73 Cr. |

| 2 | Land | 200 Ha in possession |

| 3 | Water | Tied up / Agreement Executed. |

| 4 | Equipment | Orders placed. |

| 5 | Finance | Applied to source |

| 6 | Investments already made | Rs. 1150 crore |

| 7 | Clearances | Applied for MOEF clearance through State Pollution Board. |

| 8 | Existing capacity | 65 MW CPP and 8 Itpa SI Plant |

| 9 | DPR | Prepared and apprised by the FI |

| 10 | Earlier allocation | Chotia and Madanpur (North) |

16.27 Investigation has further revealed that Screening Committee meetings were held on 20.06.2007, 21.06.2007, 22.06.2007, 23.05.2007, 30.07.2007 and 13.09.2007.

16.28 During 20.06.2007 to 23.05.2007 the applicant companies gave presentations before the Screening Committee and submitted Feed-Back forms. Sh, H.C. Gupta, Secretary, Ministry of Coal and Sh. K.S. Kropha, Joint Secretary, Ministry of Coal had attended the said meetings as Chairman and Member Convener respectively of the Screening Committee.

16.29 Investigation has further revealed that notice for the Screening Committee meeting wherein companies had to make the presentation was issued to M/s. Prakash Industries Ltd. on 06th June, 2007 under the signature of Sh. K.C, Samria, Director, Ministry of Coal. During the presentation, the applicant company had to submit the Feed Back form in 25 copies. The feed-back form was titled as “latest status of end use plant”, for which application for coal block had been made.”

16.30 Investigation has further revealed that on 21.06.2007, Sh. Ved Prakash Agarwal, CMD, Sh. HR Surana, ED(MD), Sh. K P Singh, President, Sh. AK Chaturvedi, Executive Director(CA) and Sh. Sanjay Jain, VP (Project) appeared before the Screening Committee for presentation on behalf of M/s Prakash Industries Ltd. The presentation before Screening Committee was jointly made by Sh. Ved Prakash Agarwal and Sh. AK Chaturvedi and Feed-back form consisting of the latest status of EUP was also submitted wherein the following claims regarding setting up of the EUP was made by the Company.

|

S. No |

Heads | Claim |

| 1 | Net worth as on 31.03.2006 | 532 Cr. |

| 2 | Land | 200 acres already acquired |

| 3 | Water | 23500 M3/ day tied up |

| 4 | Equipment | 15% of equipments commissioned |

| 5 | Finance | Financial closure achieved, and Rs. 250 crores already invested. |

| 6 | Investments already made | Rs. 250 crores |

| 7 | Clearances | Environment clearance for 1st phase of 125 MW already obtained and balance capacity under progress. |

| Status of Civil Clearance | 35% | |

| 8 | Existing capacity | 65 MW CPP and 8 Itpa SI Plant |

| 9 | DPR | Prepared |

| 10 | Earlier allocation

|

Chotia and Madanpur (North)” |

47. CBI is thereafter stated to have enlisted the assistance of two financial experts of Coal India Limited. According to the two experts, which were nominated by Coal India Limited, the net worth of the petitioner on verification came to Rs. 264.20 crores only. This is evident from Para 16.34 of the chargesheet which is extracted hereinbelow: –

“16.34 Thereafter, two officers of GIL namely Sh. Samiran Dutta and Smt. Sushmita Sengupta both Senior Managers (Finance) of Coal India Ltd. reported to Sh. K. S. Kropha, Joint Secretary, MoC and Sh. K C Samria, Director, CAT Section, MoC. As per the directions of the Sh. K. S. Kropha and Sh. K. C. Samria they verified the net worth of the applicant companies from the balance sheet etc submitted by the applicant companies along with their applications and submitted a report. The said net worth verification report was got typed by Sh. K C Samria but he did not obtain signatures of Sh. Samiran Dutta and Smt Sushmita Sengupta on the same. However, the said report collected from the Ministry of Coal bears the scribbles In the hand writings of Sh. K. S. Kropha. As per the said report, the net worth of M/s Prakash Industries Ltd. was calculated as Rs. 264.20 crore only as on 31.03.2006 against its claim of Rs. 532 Crores made in the application form and feedback form. The said two financial experts of QL however, did not confirm the genuineness of the said documents as these do not bear their signatures.”

48. The CBI while dealing with the issue of the land in possession of the petitioner has observed as under: –

“16.51 Investigation revealed that M/s. Prakash Industries Ltd. in Its application had claimed the requirement of land as 500 hectares and in possession 200 hectares (i.e. 494.2 acres). In the Feedback form M/s. Prakash Industries Ltd. mentioned the requirement of land as 500 acres and already acquired as 200 acres.

16.52 In the letter dated 01.09.2007 sent to SIPB, Chhattisgarh M/s. Prakash Industries Ltd. had claimed the possession of 505.89 acres of land and being in the process of acquisition of 42.68 acres of land through SIPB, 98.75 acres of land through the Forest Dept. and direct purchase of 123 acres of land.

16.53 Investigation revealed that M/s. Prakash Industries Ltd. was allotted 326 Acres of land during year 1990-91 by MP Audyogik Kendra Vikas Nigam, the predecessor of Chhattisgarh State Industrial Development Corporation (CSIDC) for a project of sponge iron Chhattisgarh State Industrial Development Corporation (CSIDC) for a project of sponge iron and other steel and alloys and purpose ancillary thereto. Further m year 2001-02, M/s. Prakash Industries Ltd. was allotted 77.05 Acres of Govt. land by CSIDC for manufacturing of sponge iron and purpose ancillary thereto and the possession of the land was also given. Subsequently, M/s. Prakash Industries Ltd. submitted another application dated 04.01.2007 for allotment of 40.897 Hectare (101.0568) of Govt. land in Distt. Janjgir Champa for the expansion of sponge iron plant which was allocated by CSIDC vide their letter dated 05.11.2007.

16.54 Investigation further revealed that In addition to the above M/s Piakash Industries Ltd had also applied for acquisition of 17,139 Hect (42 Acres) private land for expansion of their integrated steel plant to SIPB in February-March, 2007 which was forwarded to industries department vide SIPB letter dated 01.03.2007, Department of Commerce and Industries, Govt. of Chhattisgarh accorded in-principle approval for allotment of the said land to the company vide their letter dated 01.02.2008. Consequently, Collector Janjgir Champa passed the Award for 11.391 acres of land only in favour of the Company on 20.08.2010. However, till date the possession of land has not been transferred by the collector to the industries department for further transfer to M/s. Prakash Industries Ltd.

16.55 Investigation further revealed that M/s Prakash Industries ltd. had also applied for lease of 97.50 Hectares of land under Forest Conservation Act, 1988 to the Conservator of Forest, Rajpur vide their letter dated 17.10.2006 for the purpose of expansion of its integrated steel plant at Champa. After due process, the Chief Conservator of Forest Land Management vide their letter dated 12.07.2010 directed the Conservator of Forest Bilaspur to transfer 39.25 Hectare of land to M/s Prakash Industries Ltd. Finally on 29.07.2010, 39.25 Hectares of forest land was transferred to the Company by the Area Forest Officer, Champa. Thus, till date of submission of application form, Feed Back form and information to the state Govt. by the Company on 01.09.2007 no forest land was allotted and transferred to M/s Prakash Industries Ltd.

16.56 Investigation further revealed that accused A.K. ChaturvedI on behalf of M/s Prakash Industries had also executed an agreement dated 09.03.2007 with Sh. Parmeshwar Baish, a property dealer of Village Hathneora, Champa, Chhattisgarh, vide which Sh. Parmeshwar had agreed to arrange the sale of 123 acres of land at village Hathneora, Champa in favour of M/s Prakash Industries Ltd. by the villagers / land owners. However, after around one & half months only of execution of the said deed AK Chaturvedi informed Sh. Parmeshwar Baish that M/s Prakash Industries Ltd. had dropped its plan to set up a power plant and therefore, it did not require any land. Thus, M/s Prakash Industries Ltd. had no intentions to purchase any private land and execution of the agreement with Sh. Parmeshwar Bais was only an eye wash.”

49. Dealing with the tie-up with respect to water, the chargesheet alleges as under:-

“16.59 Investigation revealed that M/s. Prakash Industries was allocated 23000 CM of water vide allocation letter dated 05.10.2004 by the Water Resources Deptt., Govt. of Chhattisgarh for their Integrated Steel Plant with 100 MW CPP which included 25 MW Power Cogeneration and 75 MW FSB and consequently an agreement dated 10.12.2004 for the same was executed by Water Resources Department. Thus, the aforesaid allocation of water was not for 500 MW CPP of M/s Prakash Industries Ltd. In fact on 13.01,2008 M/s Prakash Industries Ltd. had applied for allocation of 50,000 CM per day for its 525 MW CPP for which Fatehpur coal block had been allocated to it and the same was cleared by the Water Resources Dept on 14.01.2011. Thus, the company had misrepresented regarding water tie up.”

50. CBI in the chargesheet has also found that the claim of the petitioner that it had obtained environmental clearances with respect to 125 MW of the proposed power plant was also false. This is so recorded in Para 16.63 which reads as under: –

“16.63 Thus, the company had neither applied nor been issued environment clearance for any part of the 500 MW CPP which was in feet the proposed power plant of M/s Prakash Industries Ltd. for which the coal block” had been applied for by it. The claim of M/s Prakash Industries Ltd. made in the application, feedback form and letter to SIPB that it had applied for environment clearance through State Pollution Control Board and obtained MOEF clearance for 125 MW capacity of the 1st Phase is false and it had mis-represented on this count.‖

51. Similar misstatements and misrepresentations are noted with respect to the declarations made by the petitioner in respect of equipment, civil construction, existing capacity and finance/investment made so far. It has ultimately leveled the following allegations against the petitioner: –

“16.71 In the application form and Feed Back form M/s Prakash Industries Ltd. had claimed its net-worth as Rs. 532.73 Crores. As per the Net-worth calculation Report purportedly prepared by the CIL experts its net-worth was Rs.264.20 Crores and the net-worth got calculated by the experts of PFC as per UMPP Formula, during investigation, was Rs.312.69 Crores. During investigation the net-worth of M/s Prakash Industries Ltd. was got re-calculated by the same CIL experts as per UMPP formula and it was calculated as Rs. 258.58 Crores.