2014-2022 is an important period in the economic history of India. The economy underwent a gamut of wide-ranging structural and governance reforms that strengthened the economy’s fundamentals by enhancing its overall efficiency. With an underlying emphasis on improving the ease of living and doing business, the reforms were based on the broad principles of creating public goods, adopting trust-based governance, co-partnering with the private sector for development, and improving agricultural productivity. Under normal circumstances, reforms of such scale and relevance would have accelerated economic growth. However, largely due to the balance sheet stress caused by the credit boom in the previous years and secondarily due to the one-off global shocks that followed, key macroeconomic variables such as credit growth, capital formation, and hence economic growth were adversely impacted during this period. Further, some reforms deliver results with lagged effects as their diffusion in the economy takes time.

This situation is analogous to the period 1998-2002 when transformative reforms undertaken by the government had lagged growth returns due to temporary shocks in the economy. Once these shocks faded, the structural reforms paid growth dividends from 2003. Similarly, in the present decade, the presence of strong medium-term growth magnets gives us optimism and hope that once these global shocks of the pandemic and the spike in commodity prices in 2022 fade away, the Indian economy is well placed to grow faster in the coming decade. With improved and healthier balance sheets of the banking, non-banking and corporate sectors, a fresh credit cycle has already begun, evident from the double-digit growth in bank credit over the past months. Additionally, the economy has started benefiting from the efficiency gains resulting from greater formalisation, higher financial inclusion, and economic opportunities created by digital technology-based economic reforms. Thus, India’s growth outlook seems better than in the pre-pandemic years, and the Indian economy is prepared to grow at its potential in the medium term.

Introduction

2.1 Indian economy has undergone a transformative process of New Age reforms in the last eight years. These diverse policies converge towards improving the economy’s overall efficiency and lifting its potential growth. To achieve the broader policy goal of unleashing the productive potential of the economy and its people, the reforms aimed at enhancing the ease of living and doing business at the fundamental level. The use of technology, in particular digital technology, undergirds the reforms. The economic energy and positive mindset that the reforms unleashed would have led to a sharp acceleration in growth but for the balance sheet repair of the over-leveraged domestic financial sector (banking & non-banking) and the corporate sector and secondarily to the one-off global shocks that followed.

2.2 With the impetus of the persistent structural and governance reforms introduced in the country and strong macroeconomic stability, it is essential to get a handle on the medium-term growth outlook for India. Will the economy achieve and sustain a steady growth rate once the one-off shocks recede? This chapter attempts to answer this question and concludes that the chances of India growing at its potential and for the potential growth itself to be lifted are higher than it has been in the last two decades. The chapter starts with a brief discussion of the history of India’s product and capital market reforms over the previous three decades. It further delves into the overarching philosophy behind the landmark reforms undertaken from 2014 to 2022 and elaborates on the shocks faced by the Indian economy during this period. It concludes with a discussion on the medium-term growth magnets for India.

Product and Capital Market Reforms

Initiation of the reforms- 1991

2.3 The macroeconomic imbalances of the late 1980s and early 1990s pushed the government towards introducing the structural reforms of 1991. The high combined deficit of the central and state governments, elevated inflationary pressures, and large and unsustainable current account deficit (CAD) led to a balance of payments crisis in the Indian economy.1 In response to the situation, trade and investments were liberalised in 1991. Import licensing on almost all intermediate inputs and capital goods was done away with, and the entry restrictions for firms were simplified. The new policy encouraged the entry of private sector firms by ending the public sector monopoly in many sectors and initiating the automatic approval policy for FDI up to 51 per cent. The exchange rate was made flexible and allowed to depreciate as necessary to maintain competitiveness. The rupee was made fully convertible on the current account and partially on the capital account. These reforms had a positive effect on the economy. The real growth went up from an average of 5.5 per cent during the 1980s to 6.3 per cent from FY93 to FY2000. Trade liberalisation had a visible effect on external trade as the total goods and services trade to GDP rose from 17.2 per cent in 1990 to 30.6 per cent in 2000.2

Continuity in Reforms with a Renewed Impetus

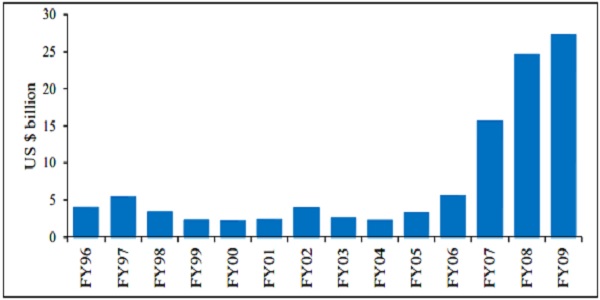

2.4 The product and capital market reforms continued slowly over the decade of the 1990s. They got a renewed impetus from the government closer to the decade’s end. Investments were liberalised further to encourage Foreign Direct Investment as a main source of non-debt-creating capital inflows (Figure II.1). The telecom sector was entirely reformed by the New Telecom Policy 1999. It was opened for private sector participation with a strengthened regulatory regime (TRAI). The reforms separated the licensing and policy functions of the government from that of an operator (BSNL). These reforms were a cornerstone for the IT sector boom in India and had widespread spillover benefits to other sectors of the economy. The policy on disinvestment and privatisation also gathered steam during this period. The government set up a dedicated Ministry to take this agenda forward. It sold equity stakes in some CPSEs and privatised companies such as Maruti Udyog, Hindustan Zinc, Bharat Aluminum, and Videsh Sanchar Nigam Limited.

Figure II.1: Foreign Direct Investment to India- Increased after the

impetus to investment liberalisation in 2000-2003

Source: RBI

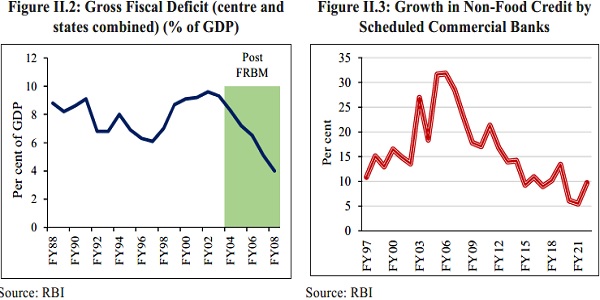

2.5 This period also marked the launch of the then largest infrastructure project of independent India, the ‘Golden Quadrilateral’. The project brought significant economic benefits to the country through enhanced connectivity, improved industrial activity, trade, and economic growth.3 Alongside this, structural policies were formulated to address the macroeconomic imbalances. The Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Act was passed to address the historic highs of the combined Gross fiscal deficit of the Government (Figure II.2). The banking system, which had accumulated bad debts during the period of economic resurgence after the 1991 reforms, was supported through the deregulation of interest rates and the enactment of the SARFAESI Act 2002. Interest rates were deregulated to promote competition amongst banks, provide more banking options to depositors, and strengthen monetary policy transmission.4 The SARFAESI Act allowed banks and financial institutions to recover their dues by proceeding against the secured assets of the borrower/guarantor without the intervention of the court/ tribunals.5 Both these reforms improved the credit situation in the economy (Figure II.3).

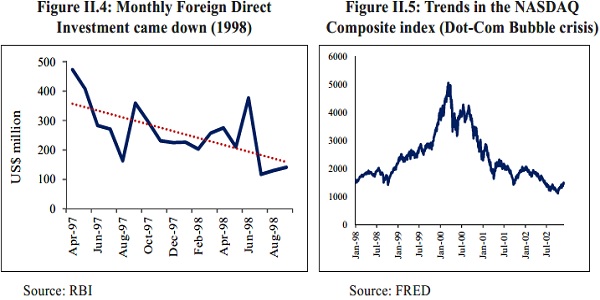

One-Off Shocks Overshadowed The Reforms of 1998-2002

2.6 The period of these reforms also witnessed a series of domestic and global shocks, which subdued investor confidence. The sanctions imposed by the US on India after India’s nuclear test led to a sharp decline in capital flows to India during the months following the nuclear tests (Figure II.4)6. The period between 2000 and 2002 also witnessed two successive droughts (Table II.1). These domestic shocks were accompanied by heightened global uncertainties resulting from the end of a tech boom and the 9/11 attacks (Figure II.5). Moreover, the balance sheets of the Indian financial system and corporate sector were under-repair during the period. Though all these factors overshadowed the immediate impact of reforms undertaken by the government then, they laid the groundwork and prepared the Indian economy structurally to participate in the Global boom which followed soon after.

Table II.1: Occurrence, number of people affected and damages

of droughts in India between 2000 and 2002

|

Date |

Location | Numbers |

| Apr 2000 | Gujarat, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Orissa, Maharashtra | Affected- 9 crore; Damage-US$588,000,000 |

| Nov 2000 | Mahasamund, Raipur, Kawardha, Rajnandgaon, Durg districts (Chhattisgarh region) | |

| May 2001 | New Delhi, Rajasthan, Gujarat, Orissa | 20 deaths |

| Jul 2002 | Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Punjab, Haryana, Delhi, Karnataka, Kerala, Nagaland, Orissa, Chhattisgarh, Himachal Pradesh, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu | Affected-30 crore;

Damage- US$910,721,000 |

Source: Samra, J. S., 2004. “Review and analysis of drought monitoring, declaration and management in India,”IWMI Working PapersH035617, International Water Management Institute. (https://www.preventionweb. net/files/1868_VL102135.pdf )

India’s Participation in The Global Boom of 2003-08

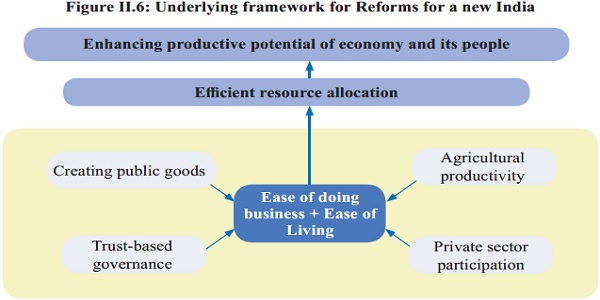

2.7 The growth dividends from the reforms of 1998-2002 were realised once these one-off shocks dissipated. The years of structural reforms had prepared the Indian economy to contribute to global growth and also benefit from it. While the global growth averaged 4.8 per cent during 2003-2008, the Indian economy grew at more than 8 per cent on average. The economic growth during the period was supported by strong capital inflows (Figure II.1), which indicated favourable domestic and external factors. Some of these included sustained momentum in domestic economic activity, better corporate performance, a conducive investment climate, positive sentiments for India as a preferred investment destination, and encouraging global liquidity conditions/ interest rates.7 This combination of structural economic reforms with their lagged effect on economic growth has parallels to what is unfolding in the Indian economy presently.

Reforms for New India-Sabka Saath Sabka Vikaas

2.8 The reforms undertaken before 2014 primarily catered to product and capital market space. They were necessary and continued post-2014 as well. The government, however, imparted a new dimension to these reforms in the last eight years. With an underlying emphasis on enhancing the ease of living and doing business and improving economic efficiency, the reforms are well placed to lift the economy’s potential growth. The broad principles behind the reforms were creating public goods, adopting trust-based governance, co-partnering with the private sector for development, and improving agricultural productivity (Figure II.6). This approach reflects a paradigm shift in the growth and development strategy of the government, with the emphasis shifted towards building partnerships amongst various stakeholders in the development process, where each contributes to and reaps the development benefits (Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikaas).

Figure II.6: Underlying framework for Reforms for a new India

2.9 While the reforms undertaken in the post-2014 period have multiple socioeconomic benefits for the economy, this chapter focuses on the growth-centric aspects of these reforms.

The forthcoming section discusses how each of the principles that anchor the new reform framework contributes to enhancing the productive potential of the economy and its people. These have more profound positive implications for India’s medium-term growth outlook.

I. Creating public goods to enhance opportunities, efficiencies and ease of living

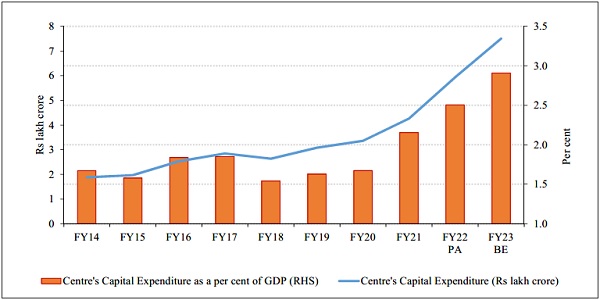

2.10 The launch of the Golden Quadrilateral project in the 2000s was the beginning of infrastructure-intensive policymaking in India, which continued sedately for another decade. A quantum leap in policy commitment and outlay for infrastructure is now visible in the last few years (Figure II.7), cushioning economic growth when the non-financial corporate sector was unable to invest due to balance sheet troubles. In doing so, the government has laid a good platform for crowding in private investments and growth in the coming decade. 8

Figure: II.7: Union government’s capital expenditure as a per cent of GDP on the rise

Source: RBI, MoSPI, O/o CGA

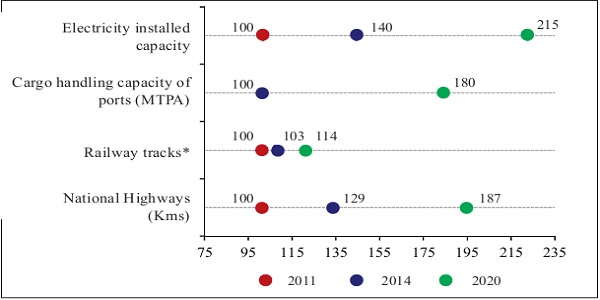

2.11 The dedicated programs for road connectivity (Bharatmala), port infrastructure (Sagarmala), electrification, railways upgradation, and operationalising new airports/ air routes (UDAN) have significantly improved the physical infrastructure in the last few years (Figure II.8). The details on the upgradation of physical infrastructure may be seen in Chapter 12. With the National Infrastructure Pipeline (NIP) in 2019 and the National Monetization Pipeline in 2021, a strong baseline for infrastructure creation and development has been put in place, providing a multitude of opportunities for foreign investment and engagement. The NIP was launched with 6,835 infrastructure projects with a projected infrastructure investment of ₹111 lakh crore. This has expanded to over 9,000 projects across 35 sub-sectors and covers economic and social infrastructure projects jointly funded by the Central Government, State Governments, and the private sector. With its strong forward and backward linkages, physical infrastructure will enhance the economy’s productivity in the medium term.

Figure II.8: Developments in critical Infrastructure Capacity

(Values are as an index with the first available value as 100)

Source: RBI Report on Currency and Finance 2022

Note: (a) Railway tracks denote Running Track Kilometres

(b): The data for national highways for 2019 is the latest available data and is shown against 2020

2.12 Besides the push to physical infrastructure, the government’s emphasis on developing public digital infrastructure during the last few years has been a game changer in enhancing the economic potential of individuals and businesses. A recently published article9 in the RBI’s Monthly Bulletin estimates that India’s core digital economy has grown at 2.4 times the overall economic growth between 2014 and 2019. With its strong forward linkages to the non-digital sectors, digitalisation strengthens potential economic growth through various channels. Some of these, such as higher financial inclusion, greater formalisation, increased efficiencies and enhanced opportunities, are discussed below.

2.13 Based on the pillars of a digital identity Aadhar, linking bank accounts with PM-Jan Dhan Yojana, and the penetration of mobile phones (JAM Trinity), the country has witnessed significant progress in financial inclusion in recent years. The population covered with bank accounts increased from 53 per cent in 2015-16 to 78 per cent in 2019-21 (as per NFHS). International evidence shows that countries at the same level of development have taken almost half a century to achieve the extent of India’s massive expansion in access to bank accounts (D’Silva et al. 2019)10. Numerous digital public goods such as digital verification (e-KYC), digital signature, digital repositories (Digilocker), and digital payments (UPI) have supported financial inclusion by improving access to formal financial services and reducing transaction costs. 11 Greater financial inclusion and access to credit incentivise higher consumption and investment, leading to higher economic growth. Some of the recently introduced digital initiatives, such as the Open Network for Digital Commerce (ONDC) and Account Aggregator framework, will open up further avenues for e-commerce market access and credit availability for smaller businesses and strengthen the expected economic growth in the medium term.

2.14 Another vital contribution of digital infrastructure has been the greater formalisation of the economy. A report in The Economist (January 2023) attributes the trends of formalisation of the workforce in India to the transformed digital financial architecture, the digitalised GST system and growth in the usage of UPI.12 The creation of digital identities such as Aadhar, registration of unorganised workers on the eshram portal, street vendors on SVANidhi, taxpaying firms on GSTN, and MSMEs on the Udayam portal, has played a significant role in the inclusion of these groups under the formal economic net. As an illustration, we can now track that out of the 1.27 crore enterprises registered on the Udyam Portal, more than 93,000 micro-enterprises have grown to become small enterprises, and 10,000 small enterprises have become medium enterprises over the last two years. 13 Creating an identity has also simplified and enabled access to formal credit for many of these groups. More than 32.7 lakh street vendors have availed of a first loan of ₹10,000 under the PM SVANidhi Scheme, and of these, more than 6.9 lakh have availed a second loan of ₹20,000. Moreover, digital systems such as the Goods and Services Tax Network (GSTN) and e-Way Bill system have enabled the formalisation of business transactions. The increasing number of GST taxpayers, from 70 lakh in 201714 to more than 1.4 crore in 2022, indicates the expansion in formal businesses. Formalisation of transactions, for even the smallest of amounts, has been possible with the wide usage of the digital payment system of UPI. The greater formalisation will enhance the productivity of individuals and businesses in the economy through improved access to credit and efficiency gains in their operations.

2.15 Gains from economic and structural reforms tend to be more significant when the binding constraints of governance have been addressed.15 Unified digital interfaces that connect various initiatives/portals have simplified governance resulting in a more efficient resource allocation in the economy. The National Single Window System for business approvals, the JanSamarth portal for credit-linked Central Government scheme, and the UMANG app for access to Central and state government services are essential steps towards enhancing the ease of doing business through the integration of existing systems. Eshram portal, with more than 28.5 crore registered workers, has been integrated with various other digital portals for easy accessibility. PM Gatishakti, the GIS-based platform that brings together multiple ministries for integrated planning and coordinated implementation of multimodal infrastructure connectivity projects, aims to reduce logistics costs. Thus, digitaltechnologies being at the forefront of the reforms provide a unique opportunity to accelerate India’s economic growth. More details on the strides in digital infrastructure may be seen in chapter 12.

II. Trust-based Governance

2.16 Building trust between the government and the citizens/businesses unleashes efficiency gains through improved investor sentiment, better ease of doing business, and more effective governance. Consistent reforms have been made in this direction during the last eight years. Simplification of regulatory frameworks through reforms such as the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) and the Real Estate(Regulation and Development) Act (RERA) have enhanced the ease of doing business. The IBC has imbibed some of the best international practices of an asset resolution mechanism. It provides an honourable exit mechanism for honest business failures and enables the release of credit locked into the stressed assets for better resource allocation. This market-driven, transparent resolution mechanism instils confidence in the financial system and attracts many new investors to invest in Indian businesses.16 A significant achievement of the IBC has been the change brought in the debtor-creditor relationship. Debtors are resolving stress early to avoid being pushed into insolvency. Until 30 September 2022, 23,417 applications for initiating the corporate insolvency resolution process (CIRP) of corporate debtors having underlying defaults of ₹7.3 lakh crore were disposed of before their admission into CIRP. 17

2.17 The other regulatory reform, Real Estate (Regulation and Development) Act (RERA), is creating a culture of transparent transactions in the real estate sector.18 The Act has transformed the real estate sector by registering real estate brokers and agents with the regulator, establishing mechanisms for the speedy redressal of disputes and enabling a single window clearance for timely approvals to the developers. The Real Estate Regulatory Authorities across the country have disposed off more than 1.06 lakh complaints. With 99262 projects and 71514 agents already registered under RERA, the Act incentivises more investments into the sector.

2.18 Another significant reform to enhance doing business has been the decriminalisation of minor economic offences under the Companies Act of 2013 (Table II.2). By introducing civil liabilities for dealing with simple defaults that do not involve fraud or where the nature of the lapse is purely procedural, the government has demonstrated its intent to promote ease of doing business for domestic and global investors. Furthermore, a trust-based approach towards compliance builds entrepreneurs’ faith in corporate institutions and motivates them to adopt fairer and more transparent business practices. After the reform, more than 1400 default cases have been decided without resorting to the court. Also, more than 4,00,000 companies have willingly rectified past defaults to avoid penalties under the Companies Act.19

Table II.2: Snapshot on decriminalisation of offences under the Companies Act, 2013

|

Pre-decriminalisation |

Post-decriminalisation Fin two phases] | |

| Total penal provisions | 134 | 124 |

| Compoundable offences [mostly fines are imposed] | 81 | 31 |

| Non-compoundable offences [serious offences where imprisonment is ordered upon conviction] | 35 | 35 |

| Defaults subject to civil liability (through In House Adjudication Mechanism) | 18 | 58 |

2.19 The removal of policy uncertainties has favourable implications for strengthening the trust between the government and its citizens. Simplifying processes by doing away with 25000 unnecessary compliances, repealing more than 1400 archaic laws, abolishing the Angel tax and removing retrospective taxation on offshore indirect transfer of assets located in India, signal the government’s resolve to ensure a non-adversarial policy environment. These efforts have improved investor sentiments and strengthened the growth potential.

2.20 In particular, the taxation ecosystem in the country has undergone substantial reforms in the post-2014 period. Tax policy reforms such as adopting a unified GST, reducing corporate tax rates, exemption of sovereign wealth funds and pension funds from taxes, and removing the Dividend Distribution tax have reduced the tax burden on individuals and businesses; and have removed the distortionary incentives from the economy. GST, for instance, has helped businesses by reducing compliances, ensuring a free flow of goods across states, doing away with the need for businesses to have a separate warehouse for every state, and hence improving the ease of doing business. The earlier indirect tax regime was origin based, and it distorted the location choices of the businesses.

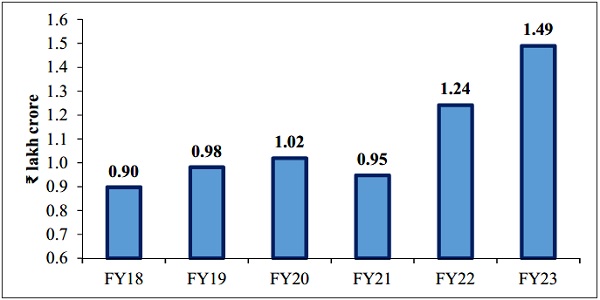

2.21 Despite tax rationalisation, a positive trend of higher tax buoyancy is visible in the economy. The notable economist Indira Rajaraman termed GST ‘a revenue success’ in 201920; thereafter, the positive GST revenue collection trends have strengthened further despite the pandemic. The average monthly gross GST collection has increased from ₹0.90 lakh crore in FY18 to ₹1.49 lakh crore in FY23 (Figure II.9). Evidence suggests that the buoyancy of the indirect tax system replaced by GST has improved in the post-GST regime (Box III.1, Chapter 3). Since other tax reforms, such as the corporate tax cut, were followed by the pandemic-led uncertainty and disruptions, their impact on collections is gradually becoming visible in higher tax collections. The Corporate tax collections for April to November 2022 have increased by 21.1 per cent on a YoY basis compared to a longer-term average YoY growth of 10.3 per cent during the corresponding period from FY13 to FY19.

Figure II.9: Rising average monthly gross GST collection

Source: Department of Revenue

2.22 One prominent reason behind the higher revenue buoyancy is the introduction of technology-backed tax governance reforms for simplifying tax processes, enhancing compliance, and improving fraud detection systems. The faceless assessment and appeal systems no longer require a physical interface between taxpayers and the Income Tax department. Moreover, multiple consistency checks possible with integrated digital systems reduce tax evasion. As an illustration, the GST return filing mechanism results in better income reporting, leading to higher direct tax collections. In this regard, the decision to share data and information between CBDT and CBIC on an automatic and regular basis is a promising reform, and it would result in efficiency gains in the tax system. These reforms augur well for future economic growth and future resource mobilisation in the economy.

III. Promoting the private sector as a co-partner in the development

2.23 A fundamental principle behind the government’s policy in the post- 2014 period has been the engagement with the private sector as a partner in the development process. The government’s disinvestment policy has been revived in the last eight years with stake sales and the successful listing of PSEs on the stock market. During FY15 to FY23 (as of 18 January 2023), an amount of about ₹4.07 lakh crore has been realised as proceeds from disinvestment through 154 transactions using various modes/instruments. The privatisation of Air India was particularly significant for re-igniting the privatisation drive. Evidence shows that privatisation has improved labour productivity and the overall efficiency of the PSUs disinvested during 1990-2015.21 The New Public Sector Enterprise Policy for Aatmanirbhar Bharat has thus been introduced to realise higher efficiency gains by minimising the presence of the government in the PSEs to only a few strategic sectors.

2.24 Significant initiatives have been introduced under Aatmanirbhar Bharat and Make in India programmes to enhance India’s manufacturing capabilities and exports across the industries. Sector-specific Production Linked incentives (PLI) have been introduced in the aftermath of the pandemic to incentivise domestic and foreign investments and to develop global Champions in the manufacturing industry. The PLI scheme will significantly boost production, exports and employment in the medium term; however, its impact will be visible only with time. Early estimates of the impact of PLI show encouraging trends in some sectors. The PLI scheme for large-scale electronics manufacturing has attracted an investment of ₹4,784 crore and contributed to a total production of ₹2.04 lakh crore, including exports of ₹80,769 crore (as of September 2022)22. The need for a dedicated government policy to support domestic industrialisation amidst foreign competition can be better appreciated from the industrialisation experiences of East Asian countries such as South Korea and Taiwan in 1960-1990. These countries supported their domestic industries during their high growth phase, while also ensuring healthy competition required for the industries to grow. 23

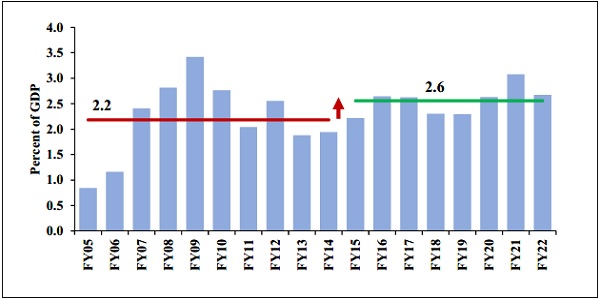

2.25 Production incentives under Aatmanirbhar Bharat also incentivise foreign investments for domestic production. The last eight years have seen further liberalisation of the policy towards foreign investors, with most sectors now open for 100% Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) under the automatic route. This has resulted in a visible structural shift in the gross FDI flows to India during the last decade. India’s gross FDI has increased from an average of 2.2 per cent of GDP during FY05-FY14 to 2.6 per cent in FY15-FY22 (Figure II.10). The highest-ever annual gross FDI inflow of USD 84.8 billion was recorded in FY22. These trends are an endorsement of India’s status as a preferred investment destination amongst global investors.

Figure II.10: Structural shift in the Gross FDI/GDP during 2014-15

Source: RBI Handbook of Statistics on the Indian Economy (FDI data); International Monetary Fund World Economic Outlook database (Oct.2020) for US dollar GDP at current prices

2.26 The government is developing enabling infrastructure for making India a cost-effective production hub. The National Logistics Policy (2022)24 has been launched to create an overarching logistics ecosystem for lowering the cost of logistics and bringing it to par with other developed countries. This would boost economic growth, provide employment opportunities, and make Indian products more competitive in the global market. Moreover, opening the strategic sectors, such as defence, mining and space, for the private sector has enhanced the business opportunities in the economy. Investment incentives and easing business compliances have created an ecosystem for the start-ups to nurture. The number of recognised Start-ups has increased from 452 in 2016 to 84,012 in 2022. More details on reforms for industries may be seen in Chapter 9.

2.27 Reforms to address the structural challenges faced by MSMEs have been a vital part of the industrial policy in recent years. Support measures for MSMEs during the pandemic in the form of the Emergency Credit Line Guarantee Scheme (ECLGS) and revision in the definition of MSMEs under the ambit of Aatmanirbhar Bharat helped them face the crisis shock. The ECLGS, in particular, has in the last two years benefited 1.14 crore MSMEs, which have availed collateral-free loans amounting to ₹2.38 lakh crore. Further measures, such as the introduction of TReDS to address the delayed payments for MSMEs, the inclusion of Retail and Wholesale trades as MSMEs, and the extension of non-tax benefits for three years in case of an upward change in the status of MSMEs, have created a resilient support system for the MSME sector to grow. The MSMEs have also benefitted from access to digital platforms for their marketing needs and easy payments. With the Open Network for Digital Commerce creating opportunities for MSMEs to access e-commerce technology and diversify their target markets, this trend will likely strengthen further. Moreover, onboarding GSTN as a Financial information provider on the Account aggregator platform will open up avenues for access to credit for MSMEs. Enhancing opportunities and productivity of the MSME sector have large-scale implications for a resilient production ecosystem, thus strengthening the growth prospects of the industry and the economy as a whole. These reforms, therefore, must continue.

IV. Enhancing productivity in agriculture

2.28 The agriculture sector in India has grown at an average annual growth rate of 4.6 per cent during the last six years. This growth is partly attributable to good monsoon years and partly to the various reforms undertaken by the government to enhance agricultural productivity. Policies such as Soil Health Cards, the Micro irrigation Fund, and organic and natural farming have helped the farmers optimise resource use and reduce the cultivation cost. The promotion of Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs) and the National Agriculture Market (e-NAM) extension Platform have empowered farmers, enhanced their resources, and enabled them to get good returns. Agri Infrastructure Fund (AIF) has supported the creation of various agriculture infrastructures. Kisan Rail exclusively caters to the movement of perishable Agri Horti commodities. Cluster Development Programme (CDP) has promoted integrated and market-led development for horticulture clusters. Support for creating a Start-up ecosystem in agriculture and allied sectors is also being provided to the farmers. All these measures are directed towards supporting the growth in agricultural productivity and sustaining its contribution to overall economic growth in the medium term.

Returns to the Economic and Structural Reforms after 2014 Shocks that the economy faced during 2014-22

2.29 Under normal circumstances, comprehensive and wide-ranging reforms undertaken in the economy during the last eight years (as covered in the previous section) would have accelerated India’s growth. But that was not to be. The ‘culprit’ is India’s balance sheet stress caused by the credit boom in previous years. As per data from the Bank for International Settlements, India’s non-financial private sector debt to GDP ratio went up from 72.9 per cent in March 2004 to 113.6 per cent by December 2010. That is an increase of 40.7 percentage points in just over six years. In rupee terms, the amount of debt accumulated by the non-financial sector went up from nearly 44 lakh crore to almost 133 lakh crore. It trebled in six years. Despite limited economic reforms, global capital flows and optimism about BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) triggered a domestic credit and investment boom that eventually proved unsustainable, as the twin deficit – fiscal and external – crisis of 2013 revealed. Thereafter the non-financial private sector debt to GDP ratio began to come down meaningfully only from 2015 onwards, dropping to a low of 83.8 per cent by December 2018. That is nearly a 30 percentage point reduction from 113.6 per cent in December 2010 over eight years.

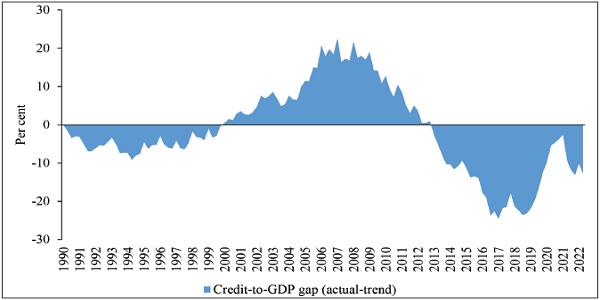

2.30 Unsurprisingly, the credit to the private non-financial sector as a per cent of GDP was consistently below its trend value for most of the second decade of the millennium, implying a negative credit gap to GDP ratio (Figure II.11). The gap worsened to an unprecedented level of 25 per cent in 2017. A statistically significant negative correlation (-0.5) between the Gross NPAs and credit growth shows that the banks’ credit supply was severely constrained due to stress in their balance sheet during the second decade.25 That explains the large negative deviation of the credit-to-GDP ratio from its trend.

Figure II.11: Quarterly Credit to GDP Gap remained negative for most of the 2010s

Source: BIS

2.31 As investments made by companies went sour, it impaired their ability to repay bank loans. Hence, banks’ non-performing assets began to rise. That set in motion a long period of repair of the financial and non-financial sector balance sheets in the second half of the last decade. The government and the RBI took several policy initiatives to help the financial sector recoup the balance sheet stress during the 2010s. Some of these such as the amendment to the SARFAESI Act 2002, implementation of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC), launch of ‘Asset Quality Review’ (AQR), introduction of prompt corrective action (PCA) framework, recapitalisation of Public Sector Banks (PSB), and merger of PSBs among others, helped in cleaning up the balance sheets of banks/corporates.

2.32 Even as the balance sheets of banks and companies began to mend and improve, came the collapse of the Infrastructure Finance and Leasing Services (IL&FS) in September 2018. It was a big non-banking financial company (NBFC) with a huge asset base. Its collapse also had a huge ripple effect on other non-banking financial entities. Few housing finance companies went under as well. Hence, housing loan disbursements were disrupted. Usually, non-banking finance companies lend to more borrowers and riskier borrowers than banks. They are refinanced by banks. Their re-financings came down in the wake of the collapse of IL&FS, a big NBFC, followed by the collapse of some housing finance companies. Therefore, bank credit growth came down to single digits towards the end of 2019, continuing into 2020. Low credit growth and hence weaker capital formation impacted economic growth.

2.33 The government responded with several measures to stem the fallout of the collapse of IL&FS and housing finance companies, including a corporate tax cut in September 2019. Soon thereafter, the pandemic struck, and the government had to address the emerging health, social and economic consequences of unprecedented nature. These have been discussed in detail in the previous two economic surveys of 2020-21 and 2021-22. These back-to-back shocks have delayed the impact of such momentous reforms on the economic growth.

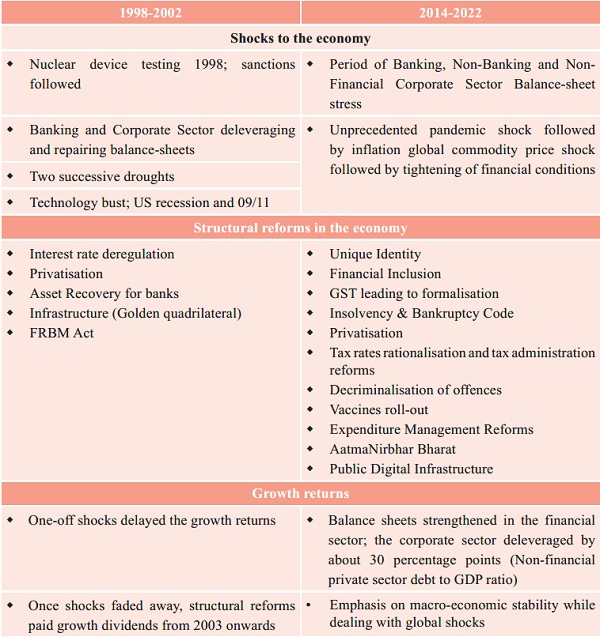

The Period 2014-2022 is Analogous to the Period 1998-2002

2.34 India’s recent economic history provides a similar parallel to this situation. During 19982002, transformative reforms were launched but yielded lagged growth dividends (Table II.3). This phenomenon was attributed to a series of one-off shocks resulting from external factors and the domestic financial sector clean-up, which overshadowed the growth returns from 1998 to 200226. By 2003, when the shocks dissipated, India participated in the global boom and grew at a higher rate. Similarly, in the present context, as the global shocks of the pandemic and the spike in commodity prices in 2022 fade away, the Indian economy is well placed to grow at its potential in the coming decade.

Table II.3: A parallel between the periods: 1998-2002 and 2014-2022

Growth Magnets in this Decade (2023-2030)

India is prepared to grow at its potential once the one-off shocks recede

2.35 After a long period of balance sheet repair in the financial and corporate sector, the financial cycle is poised to turn upward. As the health and economic shocks of the pandemic and the spike in commodity prices in 2022 wear off, the Indian economy is thus well placed to grow at its potential in the coming decade, similar to the growth experience of the economy after 2003. This is the primary reason for expecting India’s growth outlook to be better than it was in the pre-pandemic years. The sound and healthy financial system developed over the last few years will ensure efficient credit provisioning, contributing to higher growth in the coming years through higher investments and consumption. Thanks to India’s digital revolution and formalisation, banks have far more information about their customer’s credit risks than before, thus being able to make credit and pricing decisions better than before. That should make for a healthier and longer credit cycle than before. Bank credit growth has been well into double-digits for quite some time now. A recent IMF Working paper27 analyses the trends in the Credit-to-GDP ratio gap28, bank balance sheets and the GDP growth in India since 2012; and shows that better-capitalised banks result in higher credit growth, which further translates into higher GDP growth.

2.36 The digitalisation reforms and the resulting efficiency gains in terms of greater formalisation, higher financial inclusion, and more economic opportunities will be the second most important driver of India’s economic growth in the medium term. In its recent Article IV report for India, IMF highlighted that India’s successful implementation of the wide-ranging reforms and more than expected dividends from digitalisation could increase India’s medium-term growth potential. 29 These productivity-enhancing reforms along with the Government’s Skilling initiatives, will also help unleash the benefits of the demographic dividend in the coming years. In sum, various initiatives undertaken in the last eight years have bolstered India’s growth potential, and it will be reflected in actual GDP growth as the effects of one-off the shocks recede.

2.37 The evolving geo-political situation also presents an opportunity for India to benefit from the diversification of global supply chains. The last few years have exposed multinational firms to unprecedented risks due to global trade tensions, pandemic-induced supply chain disruptions, and the conflict in Europe. Firms were exposed to the risk of concentrating their production in a single country. Therefore, given the global policy uncertainty, multinational firms are gradually exploring strategies to diversify their production bases and supply chains. UNCTAD, in one of its reports, shows that ‘reshoring, diversification, and regionalisation will drive the restructuring of global value chains in the coming years’.30 With enabling policy frameworks, India presents itself as a credible destination for capital diversifying out of other countries.31 32

The recently published Chief Economists Outlook 2023 (World Economic Forum) highlights India’s opportunity to gain from these global trends of supply chain diversification.33

2.38 While the new age reforms undertaken over the last eight years form the foundation of a resilient, partnership-based governance ecosystem and restore the ability of the economy to grow healthily, further reforms are needed to ensure that economic growth can both accelerate and be sustained at higher levels, to deliver a better quality of life. The deregulation and simplification of compliances should continue to dismantle the licensing, inspection and compliance regime entirely. State governments have to address power sector issues, and the financial viability concerns of the Discoms have to be addressed. Impetus must be given to education and skilling to match the requirements of modern industry and technologies, deal with twenty-first-century challenges such as climate change and energy transition, and make the most of India’s demographic dividend. Initiatives to sensitise the population towards a healthy lifestyle should be continued. Strategies to arrest and reverse the rising obesity levels should be adopted.34 Long-range plans need to be formulated to secure the necessary metals and minerals required for energy transition and diversification. Determined efforts should be taken to make the public sector asset monetisation scheme successful in realising wide-ranging efficiency gains from the programme. If asset monetisation revenues are used to reduce public sector debt, the sovereign credit rating will improve, leading to a lower cost of capital. That will be the biggest fiscal stimulus to the economy. Reforms to reduce the compliance burden on MSMEs, enhance their access to finance and working capital and equip them with skills, knowledge and attitude to grow their businesses responsibly must continue. State governments should make conclusive progress on the various factor market reforms in different stages of completion.

2.39 In this chapter, we have shown that the Indian economy had not lost its vigour, nor have government reform measures their effectiveness. The Indian economy could have grown faster in the absence of the financial and corporate sector balance sheet stress. Even as we were looking forward to the economy being able to reap the benefits of improved and healthier balance sheets in the new decade, it was buffeted by the global pandemic followed by a sharp rise in the prices of food, fuel and fertiliser. Negative shocks will and do fade, as they did in the early years of the new millennium. Now, financial and corporate sector balance sheets are in good shape, and there is a willingness to borrow and lend. Hence, it is inevitable that the effects of these reforms will now shine through. A restored credit cycle will rejuvenate the Indian private sector capex cycle. That alone is adequate to enable India to grow at least 6 per cent per annum in real terms. On top of that, the higher economic efficiency resulting from the public digital infrastructure created over the last 6-7 years will also add 30- 50 basis points to the potential GDP growth. The growth effects of the maturation of India’s public digital infrastructure are insufficiently understood. Formalisation and financial inclusion that it has enabled are too evident to be ignored. It is a matter of time before its growth effects become persistent in the data. That is why we are optimistic that India will achieve an average of 6.5 per cent real GDP growth in the medium term. In addition, if the other reforms explained in the previous paragraph are pursued in the coming years, India’s potential GDP growth can rise to 7-8 per cent per annum in the medium term.

Notes:-

1 History of Reserve bank of India-Volume IV (https://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/RHvol-4.aspx)

2 Arvind Panagariya, 2004. “India in the 1980’s and 1990’s: A Triumph of Reforms,”IMF Working Papers2004/043, International Monetary Fund. (https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2004/wp0443.pdf)

3 Ghani, Ejaz & Grover, Arti & Kerr, William. (2012). Highway to Success: The Impact of the Golden Quadrilateral Project for the Location and Performance of Indian Manufacturing. The Economic Journal. (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ecoj.12207)

4 Reserve Bank of India RBI, 2011. “Deregulation of Savings Bank Deposit Interest Rate: A Discussion Paper,”Working Papersid:3959, eSocialSciences. (https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/Content/PDFs/DPS270411F.pdf )

5 Vinod Kumar, & Rajiv Khosla. (2017). IMPLEMENTATION AND IMPACT OF SARFAESI ACT 2002.International Education and Research Journal (IERJ),3(5). (http://ierj.in/journal/index.php/ierj/article/view/863/869); https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1578808

6 Daniel Morrow & Michael Carriere (1999) The economic impacts of the 1998 sanctions on India and Pakistan, The Nonproliferation Review, 6:4,1-16. (https://www.nonproliferation.org/wp-content/uploads/npr/morrow64.pdf)

7 Mohan, Rakesh, (2008), Capital flows to India, p. 235-263 in Settlements, Bank for International eds., Financial globalisation and emerging market capital flows, vol. 44, Bank for International Settlements, (https://www.bis.org/publ/bppdf/bispap44m.pdf)

8 ‘Crowding-Out or Crowding-In? Public and Private Investment in India’, IMF Working Paper (WP/15/264), December 2015 (https://www. imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/31/Crowding-Out-or-Crowding-In-Public-and-Private-Investment-in-India-43470)

9 Dhirendra Gajbhiye et al. (2022), ‘Measuring India’s Digital Economy’, RBI Monthly Bulletin December 2022 (https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/ rdocs/Bulletin/PDFs/05ART201220221265B8E871824B98970F03E87228C0FE.PDF)

10 D’Silva, Derryl and Filková, Zuzana and Packer, Frank and Tiwari, Siddharth, The Design of Digital Financial Infrastructure: Lessons from India (December 15, 2019). BIS Paper No. 106 (https://www.bis.org/publ/bppdf/bispap106.pdf)

11 Swallow,Haksar, And Patnam (2021), Stacking Up Financial Inclusion Gains In India, IMF Finance & development (https://www.imf.org/ external/pubs/ft/fandd/2021/07/india-stack-financial-access-and-digital-inclusion.htm)

12 ‘Imagine an India without hawkers’, The Economist January 2023. (https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2023/01/05/ imagine-an-india-without-hawkers)

13 https://pqars.nic.in/annex/257/AU904.pdf

14 PMEAC Report- ‘GST-Connecting the remaining dots’, June 2022

15 IMF World Economic Outlook 2019

16 Sahoo, M. S., & Guru, A. (2020). Indian Insolvency Law.Vikalpa,45(2), 69–78 (https://www.ies.gov.in/pdfs/Indian-Insolvency-Law-Dr-MS-Sahoo-and-Dr-Anuradha-Guru.pdf)

17 IBBI Quarterly newsletter (Jul-Sep 2022)

18 Speech by RBI Deputy Governor, R. Gandhi on ‘Improving investor interest – Recent Legislative and Regulatory Measures’ (2017) (https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/Bulletin/PDFs/3IMITERST460080CE62954FB5960719A4B855C20C.PDF )

19 Using the Companies Fresh Start Scheme

20 Monograph titled ‘The evolving GST’ delivered by Indira Rajaraman as the Chelliah Memorial Lecture at the Madras School of Economics in 2019. (https://www.mse.ac.in/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Monograph-43.pdf )

21 Chhibber, Ajay & Gupta, Swati, 2017. “Bolder Disinvestment or Better Performance Contracts? Which Way Forward for India’s State-Owned Enterprises,”Working Papers17/205, National Institute of Public Finance and Policy.

22 https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1885189

23 Jostein Hauge, 2020. “Industrial policy in the era of global value chains: Towards a developmentalist framework drawing on the industrialisation experiences of South Korea and Taiwan,” The World Economy, Wiley Blackwell, vol. 43(8), pages 2070-2092, August.

24 Details in Chapter 12

25 Muduli, S. and Behera, H., 2021. Bank capital and monetary policy transmission in India. Macroeconomics and Finance in Emerging Market Economies, pp.1-25. (https://bit.ly/3J9xvNG)

26 Refer Paragraph 6 of this chapter for details

27 IMF Working paper (WP/22/137)- Financial Sector and Economic Growth in India by Margaux MacDonald;TengTeng Xu (July 2022) – (https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2022/07/08/Financial-Sector-and-Economic-Growth-in-India-520580)

28 Difference between actual ratio and its trend value

29 https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2022/12/21/India-2022-Article-IV-Consultation-Press-Release-Staff-Report-and-State-ment-by-the-527283

30 UNCTAD World Investment report 2020 (https://unctad.org/news/covid-19-will-likely-transform-global-production-says-un-report; https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/wir2020_en.pdf)

31 ‘Helped by PLI scheme, Apple’s India exports set to hit Rs 20,000 crore’, Business Standard, December 2022 (https://www.business-standard.com/article/companies/helped-by-pli-scheme-apple-s-iphone-exports-from-india-hit-record-122121200940_1.html)

32 ‘India to get more Apple suppliers as iPhone production picks up: Experts’, Business Standard, December 2022 (https://www.business-standard.com/article/technology/india-to-get-more-apple-suppliers-as-iphone-production-picks-up-experts-122121900505_1.html)

33 Chief Economists Outlook 2023 (World economic Forum)- https://www.weforum.org/reports/chief-economists-outlook-jan-2023

34 As per National Family Health Survey 5, Obesity is rising for both men and women across all states .