Case Law Details

Reckitt Benckiser India Private Limited Vs Union of India & Ors (Delhi High Court)

The Delhi High Court has upheld the validity of the anti-profiteering provisions under the Goods and Services Tax (GST) law, marking a significant development in India’s taxation landscape.

The anti-profiteering provisions under the GST law were introduced to ensure that businesses pass on the benefits of tax rate reduction or input tax credit to the consumers. This is done by reducing prices proportionately. The aim is to prevent unjust enrichment at the expense of the consumer.

A petition was filed challenging the constitutional validity of these provisions. The petitioner argued that the provisions were vague and lacked clear guidelines, leading to arbitrary and discriminatory application.

The Delhi High Court dismissed the petition, upholding the validity of the anti-profiteering provisions. The court observed that the provisions were not vague and had sufficient guidelines for implementation. It further noted that the provisions were in line with the constitutional goal of ensuring social and economic justice.

The court also emphasized the role of the National Anti-Profiteering Authority (NAA) in ensuring compliance with these provisions. The NAA has been entrusted with the responsibility of ensuring that the benefits of tax reduction or input tax credit are passed on to the consumers.

This verdict has significant implications for businesses operating under the GST regime. It reinforces the obligation of businesses to pass on the benefits of tax reduction or input tax credit to the consumers. Businesses failing to comply with these provisions may face penalties.

The verdict also provides legal backing to the actions of the NAA. This is expected to strengthen the authority’s role in curbing profiteering practices.

The Delhi High Court’s decision to uphold the validity of the anti-profiteering provisions under the GST law is a welcome move. It reaffirms the government’s commitment to protect consumers’ interests and ensure fair pricing practices. Businesses must take note of this verdict and ensure compliance with the GST law.

FULL TEXT OF THE JUDGMENT/ORDER OF DELHI HIGH COURT

1. Present writ petitions have been filed challenging the constitutional validity of Section 171 of the Central Good and Services Tax Act, 2017 (for short ‘Act, 2017’) and Rules 122, 124, 126, 127, 129, 133 and 134 of the Central Good and Services Tax Rules, 2017 (for short ‘Rules, 2017’) as well as legality of the notices proposing imposition or orders imposing penalty issued by the National Anti-Profiteering Authority (‘NAA’) under Section 122 of the Act, 2017 read with Rule 133(3)(d) of the Rules, 2017 and the final orders passed by NAA, whereby the petitioners, who are companies running diverse businesses ranging from hospitality, Fast-Moving Consumer Goods (‘FMCG’) to real estate, have been directed in accordance with Section 171 of Act, 2017, to pass on the commensurate benefit of reduction in the rate of tax or the Input Tax Credit to its consumers / recipients along with interest.

2. Learned counsel for the parties prayed that this Court may first decide the plea of constitutional validity of Section 171 of Act, 2017 as well as Rules 122, 124, 126, 127, 129, 133 and 134 of the Rules, 2017. They stated that only in the event this Court were to uphold the constitutional validity of the aforesaid Section and Rules, would the need to examine the matters on merits arise.

3. Accepting the suggestion of the learned counsel for the parties, this Court proceeded to hear the issue of constitutional validity of Section 171 of Act, 2017 as well as Rules 122, 124, 126, 127, 129, 133 and 134 of the Rules, 2017. The said provisions are reproduced hereinbelow:-

Section 171

“171. Anti-profiteering measure

(1) Any reduction in rate of tax on any supply of goods or services or the benefit of input tax credit shall be passed on to the recipient by way of commensurate reduction in prices.

(2) The Central Government may, on recommendations of the Council, by notification, constitute an Authority, or empower an existing Authority constituted under any law for the time being in force, to examine whether input tax credits availed by any registered person or the reduction in the tax rate have actually resulted in a commensurate reduction in the price of the goods or services or both supplied by him.

(3) The Authority referred to in sub-section (2) shall exercise such powers and discharge such functions as may be Authority.

[(3A) Where the Authority referred to in sub-section (2), after holding examination as required under the said sub-section comes to the conclusion that any registered person has profiteered under sub-section (1), such person shall be liable to pay penalty equivalent to ten per cent. of the amount so profiteered:

Provided that no penalty shall be leviable if the profiteered amount is deposited within thirty days of the date of passing of the order by the Authority.

Explanation. — For the purposes of this section, the expression “profiteered” shall mean the amount determined on account of not passing the benefit of reduction in rate of tax on supply of goods or services or both or the benefit of input tax credit to the recipient by way of commensurate reduction in the price of the goods or services or both.]

Rule 122

122.Constitution of the Authority.- The Authority shall consist of,-

(a) a Chairman who holds or has held a post equivalent in rank to a Secretary to the Government of India; and (b) four Technical Members who are or have been Commissioners of State tax or central tax [for at least one year] or have held an equivalent post under the existing law, to be nominated by the Council.

Rule 124

124. Appointment, salary, allowances and other terms and conditions of service of the Chairman and Members of the Authority:-

(1) The Chairman and Members of the Authority shall be appointed by the Central Government on the recommendations of a Selection Committee to be constituted for the purpose by the Council.

(2) The Chairman shall be paid a monthly salary of Rs. 2,25,000 (fixed) and other allowances and benefits as are admissible to a Central Government officer holding posts carrying the same pay: Provided that where a retired officer is selected as a Chairman, he shall be paid a monthly salary of Rs. 2,25,000 reduced by the amount of pension.

[(3) The Technical Member shall be paid a monthly salary and other allowances and benefits as are admissible to him when holding an equivalent Group ‘A’ post in the Government of India: Provided that where a retired officer is selected as a Technical Member, he shall be paid a monthly salary equal to his last drawn salary reduced by the amount of pension in accordance with the recommendations of the Seventh Pay Commission, as accepted by the Central Government.]

(4) The Chairman shall hold office for a term of two years from the date on which he enters upon his office, or until he attains the age of sixty- five years, whichever is earlier and shall be eligible for reappointment:

Provided that [a] person shall not be selected as the Chairman, if he has attained the age of sixty-two years. [Provided further that the Central Government with the approval of the Chairperson of the Council may terminate the appointment of the Chairman at any time.]

(5) The Technical Member of the Authority shall hold office for a term of two years from the date on which he enters upon his office, or until he attains the age of sixty-five years, whichever is earlier and shall be eligible for reappointment:

Provided that [a] person shall not be selected as a Technical Member if he has attained the age of sixty-two years. [Provided further that the Central Government with the approval of the Chairperson of the Council may terminate the appointment of the Technical Member at any time.]

Rule 126

126. Power to determine the methodology and procedure

The Authority may determine the methodology and procedure for determination as to whether the reduction in the rate of tax on the supply of goods or services or the benefit of input tax credit has been passed on by the registered person to the recipient by way of commensurate reduction in prices.

Rule 127

127. Duties of the Authority.

It shall be the duty of the Authority,-

(i) to determine whether any reduction in the rate of tax on any supply of goods or services or the benefit of input tax credit has been passed on to the recipient by way of commensurate reduction in prices;

(ii) to identify the registered person who has not passed on the benefit of reduction in the rate of tax on supply of goods or services or the benefit of input tax credit to the recipient by way of commensurate reduction in prices;

(iii) to order,–

(a) reduction in prices;

(b) return to the recipient, an amount equivalent to the amount not passed on by way of commensurate reduction in prices along with interest at the rate of eighteen percent. from the date of collection of the higher amount till the date of the return of such amount orrecovery of the amount not returned, as the case may be, in case the eligible person does not claim return of the amount or is not identifiable, and depositing the same in the Fund referred to in section 57;

(c) imposition of penalty as specified in the Act; and

(d) cancellation of registration under the Act.

[(iv) to furnish a performance report to the Council by the tenth [day] of the close of each quarter.]

Rule 129

129. Initiation and conduct of proceedings.-(1)Where the Standing Committee is satisfied that there is a prima-facie evidence to show that the supplier has not passed on the benefit of reduction in the rate of tax on the supply of goods or services or the benefit of input tax credit to the recipient by way of commensurate reduction in prices, it shall refer the matter to the Director General of [Anti-profiteering] for a detailed investigation.

(2) The Director General of [Anti-profiteering] shall conduct investigation and collect evidence necessary to determine whether the benefit of reduction in the rate of tax on any supply of goods or services or the benefit of input tax credit has been passed on to the recipient by way of commensurate reduction in

(3) The Director General of [Anti-profiteering] shall, before initiation of the investigation, issue a notice to the interested parties containing, inter alia, information on the following, namely:-

(a) the description of the goods or services in respect of which the proceedings have been initiated;

(b) summary of the statement of facts on which the allegations are based; and

(c) the time limit allowed to the interested parties and other persons who may have information related to the proceedings for furnishing their reply.

(4) The Director General of [Anti-profiteering] may also issue notices to such other persons as deemed fit for a fair enquiry into the matter.

(5) The Director General of [Anti-profiteering] shall make available the evidence presented to it by one interested party to the other interested parties, participating in the proceedings.

(6) The Director General of [Anti-profiteering] shall complete the investigation within a period of [six] months of the receipt of the reference from the Standing Committee or within such extended period not exceeding a further period of three months for reasons to be recorded in writing [as may be allowed by the Authority] and, upon completion of the investigation, furnish to the Authority, a report of its findings along with the relevant records.

Rule 133

133. Order of the Authority.

(1) The Authority shall, within a period of [six] months from the date of the receipt of the report from the Director General of [Anti-profiteering] determine whether a registered person has passed on the benefit of the reduction in the rate of tax on the supply of goods or services or the benefit of input tax credit to the recipient by way of commensurate reduction in prices.

(2) An opportunity of hearing shall be granted to the interested parties by the Authority where any request is received in writing from such interested parties.

[(2A) The Authority may seek the clarification, if any, from the Director General of Anti Profiteering on the report submitted under sub-rule (6) of rule 129 during the process of determination under sub-rule (1).]

[(3) Where the Authority determines that a registered person has not passed on the benefit of the reduction in the rate of tax on the supply of goods or services or the benefit of input tax credit to the recipient by way of commensurate reduction in prices, the Authority may order –

(a) reduction in prices;

(b) return to the recipient, an amount equivalent to the amount not passed on by way of commensurate reduction in prices along with interest at the rate of eighteen per cent. from the date of collection of the higher amount till the date of the return of such amount or recovery of the amount including interest not returned, as the case may be;

(c) the deposit of an amount equivalent to fifty per cent. of the amount determined under the above clause[along with interest at the rate of eighteen per cent. from the date of collection of the higher amount till the date of deposit of such amount] in the Fund constituted under section 57 and the remaining fifty per cent. of the amount in the Fund constituted under section 57 of the Goods and Services Tax Act, 2017 of the concerned State, where the eligible person does not claim return of the amount or is not identifiable;

(d) imposition of penalty as specified under the Act; and

(e) cancellation of registration under the Act.

Explanation: For the purpose of this sub-rule, the expression, “concerned State” means the State [or Union Territory] in respect of which the Authority passes an order.]

[(4) If the report of the Director General of [Anti-profiteering] referred to in sub-rule (6) of rule 129 recommends that there is contravention or even non-contravention of the provisions of section 171 or these rules, but the Authority is of the opinion that further investigation or inquiry is called for in the matter, it may, for reasons to be recorded in writing, refer the matter to the Director General of [Anti-profiteering] to cause further investigation or inquiry in accordance with the provisions of the Act and these rules.]

[(5) (a) Notwithstanding anything contained in sub-rule (4), where upon receipt of the report of the Director General of Anti-profiteering referred to in sub-rule (6) of rule 129, the Authority has reasons to believe that there has been contravention of the provisions of section 171 in respect of goods or services or both other than those covered in the said report, it may, for reasons to be recorded in writing, within the time limit specified in sub-rule (1), direct the Director General of Anti-profiteering to cause investigation or inquiry with regard to such other goods or services or both, in accordance with the provisions of the Act and these rules.

(b) The investigation or enquiry under clause (a) shall be deemed to be a new investigation or enquiry and all the provisions of rule 129 shall mutatis mutandis apply to such investigation or enquiry.]”

Rule 134

134. Decision to be taken by the majority.- (1) A minimum of three members of the Authority shall constitute quorum at its meetings.

(2) If the Members of the Authority differ in their opinion on any point, the point shall be decided according to the opinion of the majority of the members present and voting, and in the event of equality of votes, the Chairman shall have the second or casting vote.”

ARGUMENTS ON BEHALF OF THE PETITIONERS

4. Mr. P. Chidambaram, Mr. S. Ganesh, Mr. Tarun Gulati, Mr. Chinmoy Pradip Sharma and Mr.Pritesh Kapoor, learned Senior counsel as well as Mr. V. Lakshmikumaran, Mr. Monish Panda, Mr. Rohan Shah, Mr. Abhishek A. Rastogi, Mr. Tushar Jarwal, Mr. Sparsh Bhargava, Mr. Puneet Aggarwal, Mr. Sujit Ghosh, Mr. K. S. Suresh, Mr. Nikhil Gupta, Mr. Shashank Shekhar and Mr. Priyadarshi Manish, learned counsel addressed arguments on behalf of the petitioners.

5. Learned counsel for the petitioners submitted that Section 171(1) of the Act, 2017 and the Rules 126, 127 and 133 of the Rules, 2017 framed thereunder are unconstitutional as they are beyond the legislative competence of Parliament. They submitted that the impugned provisions do not fall within the law-making power of Parliament under Article 246A of the Constitution of India.

6. Some of the learned counsel for the petitioners submitted that the anti- profiteering provision, as provided under Section 171 of the Act, 2017, is in the nature of a tax or financial exaction. They submitted that a tax can be levied from a subject only if there is a specific and unequivocal provision in the parent statute authorising such an exaction. According to them, such a financial exaction cannot be made lawfully by a subordinate legislation, when there is no empowering provision in the parent statute. In support of their submissions, they relied on the decisions of the Supreme Court in Ahmedabad Urban Development Authority v. Sharakumar Jayantikumar Pasawala, (1992) 3 SCC 285 and V.S. Sugars v. Govt. of A.P., (1999) 4 SCC 192.

7. Learned counsel for the petitioners further submitted that the impugned Section and Rules suffer from vice of excessive delegation as they delegate essential legislative functions to the Additionally, they submitted that the impugned provisions are ambiguous, arbitrary, violative of Article 14 and confer excessive powers on NAA to determine profiteering as no guidelines and/or legislative policy for the exercise of such powers by the authority so constituted have been laid down in the statute. They submitted that the failure to provide clear statutory guidance for exercise of powers by NAA in the formulation of such methodology amounts to “delegation of essential legislative function” as these formulations were essential and therefore, the same should have been stipulated by the Legislature. They submitted that it is settled law that the legislative authority cannot be delegated under a statute without appropriate guidelines or safeguards. In support of their submissions, they relied on the judgment of the Supreme Court in Ramesh Birch vs. Union of India, 1989 Supp SCC 430.

8. They submitted that it is settled law that delegatus non potest delegare which essentially means that a delegatee cannot further delegate unless expressly or impliedly authorized. They contended that the Legislature vide Section 171 of the Act, 2017 delegated the authority to determine/prescribe powers and functions of NAA to the Executive i.e. the Government of India. They submitted that the Government of India by way of Rule 126 of the Rules, 2017, contrary to the legislative mandate contained in Section 171 of the Act, 2017, further delegated the power to NAA to determine the methodology and procedure for determining whether the reduction in taxes or the benefit of Input Tax Credit had been passed on to the recipients. They stated that even NAA did not issue any guidelines as to how to determine profiteering. In support of their submission, they relied on the judgment of the Supreme Court in Barium Chemicals Ltd. & Ors. v Company Law Board & [AIR 1967 SC 295].

9. They submitted that the term ‘commensurate’ is not defined in the Act, 2017 and the expression ‘profiteering’ in Section 171 is dependent upon the scope and meaning of the phrase ‘commensurate reduction in the price’. According to them, as a result of this circular reasoning, NAA had complete and unfettered discretion to determine the extent of profiteering. They pointed out that the definition of profiteering inserted by way of amendment (that came into force only on 01st January, 2020) is vague and uncertain as to how the amount of profiteering or commensurate reduction in price has to be determined and therefore, the same is ex facie arbitrary and violative of Articles 14 and 19(1)(g) of the Constitution of India. They pointed out that even NAA, in the orders passed by it, had not been consistent in its interpretation of the term “commensurate reduction”.

10. They stated that without stipulating the specifics of the methodology to be adopted to determine profiteering, the petitioners could not have been asked to reduce prices. They contrasted the lack of guidelines in Section 171 of the Act, 2017 with Section 9A of the Customs Tariff Act, 1975 which lays down the broad guidelines on the basis of which the extent of dumping and anti-dumping duty is to be quantified and Section 19(3) of the Competition Act, 2002, which lays down the factors to be taken into consideration while determining whether an agreement has an appreciable adverse effect. They stated that in the absence of any guidelines, NAA had acted arbitrarily as is evident from the varied approaches taken by it while adjudicating cases of entities belonging to the same industry and dealing with similar products.

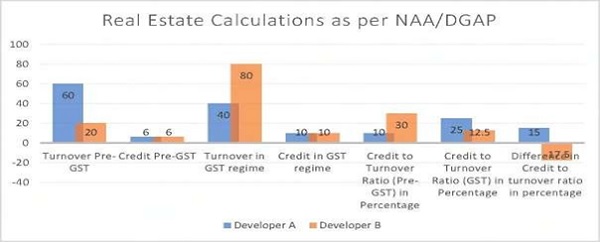

11. Learned counsel for the petitioners emphasised that the formula used by the respondents, for instance, for real estate companies during the course of investigation/adjudication, had not been They stated that the methodology adopted by NAA and the Director General of Anti-Profiteering (‘DGAP’) to arrive at the profiteering amount of the real estate industry was generally based on the difference between the ratio of Input Tax Credit to turnover under the pre-Goods and Services Tax and post-Goods and Services Tax period. To drive home the point that the methodology adopted by the respondents was flawed, the learned counsel for the petitioners gave an illustration of the contrasting results one would get after calculating the amount profiteered/required to be passed on in case of two identical real estate projects being developed by Developers A & B with the only difference being the advance payment received by them prior to the Goods and Services Tax Regime. They stated that assuming that two Developers (A & B) commenced construction of the two identical projects (having hundred flats of rupees one crore each) in 2017 and the projects were executed at an identical pace with identical inputs and with Developer A receiving sixty per cent of the amount (total sale price of the project) as advance during the pre-Goods and Services Tax period, Developer B receiving only twenty per cent as advance during that period, with all other factors being identical (like the credit availed/available during the pre-Goods and Services Tax period), the credit to turnover ratio for the two projects would vary drastically depending on the time when the payments from the customers were received. According to the petitioners, if the methodology adopted by NAA /DGAP is to be accepted, Developer A would be required to pass on 15% benefit to the flat- buyers and Developer B who received 80% of the payment/amount post-Goods and Services Tax receive would be required to pass no benefit to the flat-buyers. A graphical representation of the same, as furnished by the petitioners, is as follows:

12. They stated that it is for this reason, the percentage of credit to turnover ratio (in Goods and Services Tax regime) had varied from 2% (in Vatika Limited, Case No. 64/2019) to 20.98% (in Emaar MGF Land Ltd, Case No. 26/2020) in the orders passed by NAA.

13. Learned counsel for the petitioners in Writ Petition 13657/2022 pointed out that DLF calculated the total savings on account of introduction of Goods and Services Tax for each project. He stated that the total savings/benefits were then divided by total area to arrive at the per square feet benefit to be passed on to each flat buyer. He stated that as a result the flat-buyers with equal area received equal benefit. In contrast to this, he pointed out that the NAA/DGAP calculated the benefit by comparison of ratios as explained above and then computed the profiteered amount as a percentage of consideration received from each flat-buyer in the Goods and Services Tax regime. Therefore, as per NAA/DGAP, similarly placed flat-buyers received inconsistent benefits. For the project Camellias, the benefits computed by both NAA/DGAP & DLF are tabulated below:

|

DLF- PROJECT (Camellilas) |

||||||

| S. No. | Customer | Unit Number | Area of unit | Percentage of benefit computed by DGAP | Amount Computed by DGAP | Benefit passed on by petitioner |

| 1. | Gopal Chopra | CM405A | 7361 Sq.Ft. | 1.18% | 83,274 | 4,88,500 |

| 2. | Rachna Sawhney | CM504A | 7361 Sq.Ft. | 1.18% | 83,450 | 4,88,500 |

| 3. | Rachna Sawhney | CM505A | 7361 Sq.Ft. | 1.18% | 83,450 | 4,88,500 |

| 4. | Anil Sarin | CM510A | 7361 Sq.Ft. | 1.18% | 99,874 | 4,88,500 |

| 5. | S J Rubber Industries Ltd. | CM504B | 7361 Sq.Ft. | 1.18% | 83,265 | 4,88,500 |

| 6. | Splendid Residences Pvt. Ltd. | CM419A | 7361 Sq.Ft. | 1.18% | 11,328 | 4,88,500 |

| 7. | Rachna Sawhney | CM503B | 7361 Sq.Ft. | 1.18% | 83,450 | 4,88,500 |

| 8. | Vineet Kanwar | CM418B | 7361 Sq.Ft. | 1.18% | 2,30,148 | 4,88,500 |

| 9. | Vishal Swara | CM516B | 7361 Sq.Ft. | 1.18% | 1,47,047 | 4,88,500 |

| 10. | Sanjeev Aggarwal | CM819B | 9419 Sq.Ft. | 1.18% | 10,01,928 | 6,25,139 |

| 11. | Mohan Agarwal | CM804B | 9419 Sq.Ft. | 1.18% | 20,66,050 | 6,25,139 |

| 12. | Deep Kalra | CM818B | 9419 Sq.Ft. | 1.18% | 33,72,998 | 6,25,139 |

| 13. | Action Construction Equipment Ltd. | CM602A | 9419 Sq.Ft. | 1.18% | 34,356 | 6,25,139 |

14. They also submitted that determination of profiteering can be made at different levels such as entity level, Stock Keeping Unit (hereinafter referred to as ‘SKU’) level, product level, customer level Hence, an assessee intending to comply with the law has no way of ensuring whether its methodology is in compliance with Section 171(1) of the Act, 2017 or not.

15. Learned counsel for the petitioners also submitted that the operation of Section 171 of the Act, 2017 amounted to price-fixing and is therefore violative of Articles 19(1)(g) and 300A of the Constitution. They submitted that according to NAA’s interpretation of Section 171 of the Act, 2017, once any of the events contemplated in Section 171 of the Act, 2017 occurs, i.e. either there is reduction in tax rate or benefit of Input Tax Credit is availed, then the price of the product must be adjusted to (a) the extent of the tax reduced and/or (b) the extent of increase in the credit They stated that there is no clarity on adjustments allowed on account of rise either in input costs or in customs duty on import of inputs, supply and demand conditions and other factors which impact pricing. They submitted that Section 171 of the Act, 2017, to the extent it eliminates all factors from consideration in price fixation, other than the rate of tax and credit availability, was clearly excessive, disproportionate and unwarranted.

16. They pointed out that similar anti-profiteering provisions had been introduced in Australia (in 2000) and in Malaysia (in 2015) to ensure that the benefit of reduction of tax rate was passed on to the They stated that the provisions so introduced prescribed clear policy guidelines before imposing the restrictive conditions.

17. They stated that when Australia implemented the Goods and Services Tax replacing the erstwhile Wholesale Sales Tax, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (‘ACCC’) was entrusted with the responsibility to oversee pricing responses to the introduction of Goods and Services Tax for a period of three years between 1999 and They stated that Section 75AU of the Trade Practices Act, 1974 which prohibited price exploitation in relation to the New tax System provided that factors such as increase in supplier’s input costs, supply and demand conditions and other relevant factors shall be taken into consideration while determining price exploitation. They further stated that Section 75AV(1) of the aforesaid Act provided that the ACCC must formulate detailed guidelines to explain when prices may be regarded to be in contravention of the price exploitation provision. They stated that the ACCC had framed detailed guidelines in July, 1999 which were later revised in March, 2000 after taking inputs from all stakeholders. It was pointed out that the fundamental principle laid down in the aforesaid guidelines was based on a ‘net dollar margin rule’. According to them, the said guidelines enumerated all the relevant factors to be taken into consideration for price adjustments and provided for considering the increase in procurement cost and additional costs due to the tax change. They stated that it also allowed averaging the impact of taxes and costs across goods or services under specific circumstances.

18. While referring to the Goods and Services Tax system introduced in Malaysia, they stated that the Anti- Profiteering measures had been incorporated under the Price Control and Anti-Profiteering Act, 2011 to control prices of goods, charges of services and to prohibit unreasonably high profiteering by They stated that making unreasonably high profit was an offence under Section 14 of the said Act. They further stated that Section 15 of the said Act provided that the Minister shall prescribe the mechanism to determine whether the profit is unreasonably high considering different conditions and taking into consideration factors such as: tax imposition, suppliers’ cost, supply and demand conditions and other relevant matters in relation or price of goods and services etc. It was pointed out that detailed guidelines were laid down under the Regulations issued in 2014 and 2016.

19. Learned counsel for the petitioners further submitted that Section 171 of the Act, 2017 is manifestly arbitrary and unreasonable, as it does not fix a period of time during which the reduced prices of the goods and services had to be They emphasised that the time-frame for which an assessee could be subject to the discipline of Section 171 of the Act, 2017 has been left undefined and open-ended. According to them, this indefinite obligation hinders the petitioners’ right to trade and commerce and hence, the same is violative of Articles 14 and 19(1)(g) of the Constitution of India.

20. They further stated that price reduction is not the only method by which commensurate benefit can be passed on to the recipient. They stated that an increase in the volume or weight of the product being sold for the same price is an equally effective and legal way of commensurately reducing the price of the They stated that mandating price reduction as the only way to pass the commensurate benefit to the recipient is manifestly arbitrary and unreasonable.

21. Learned counsel for the petitioner in P.(C) 12557/2022, M/s. L’Oreal India Pvt. Ltd., stated that in the FMCG industry, for low priced products, since the resultant reduction in price is often miniscule, it was not feasible to pass on the benefit because of the restriction in the Legal Metrology Act, 2009 and Legal Metrology (Packaged Commodities) Rules, 2011 that require the prices of the goods to be rounded off to the nearest fifty paisa. In support of his contention, he referred to the following table:

|

Original MRP |

Price exclusive of 28% GST | 18% GST | Ideal revised MRP | MRP suggested by Respondent |

| 5 | 3.90625/- | 0.703125/- | 4.609375/- | 4.5/- |

| 4 | 3.125/- | 0.5625/- | 3.6874/- | 3.5/- |

| 3 | 2.34375/- | 0.421875/- | 2.765625/- | 3/- |

| 2 | 1.5625/- | 0.28125/- | 1.84375/- | 2/- |

22. Therefore, according to him, there is a legal impossibility in reducing the Maximum Retail Price (‘MRP’). As a result he stated that some of the companies had passed on the commensurate benefit by way of increasing the grammage. He pointed out that NAA vide order dated 24th December, 2018 passed in Ankit Kumar Bajoria M/s Hindustan Unilever Ltd., Case No.20/2018, had accepted the practice of increasing grammage. However, this practice had not been accepted as a mode of passing on commensurate benefit by NAA in subsequent orders.

23. Learned counsel for the petitioners pointed out that there is no provision of appeal against the orders passed by NAA. They submitted that the absence of a provision to appeal means that there is no judicial oversight over the decisions of NAA and indicates that there is a presumption that the findings of NAA are They submitted that Tribunals and Authorities which exercise functions similar to NAA have a robust appellate mechanism. They submitted that lack of a provision to appeal against the findings of NAA makes the Act, 2017 unconstitutional.

24. They submitted that Rule 124 of Rules, 2017 to the extent it deals with appointment and terms and conditions of service of the Chairman and Members of NAA is not in consonance with Article 50 of the Constitution of India as there is scope for governmental interference in the functioning of NAA.

25. Learned counsel for the petitioners submitted that NAA essentially determines the rights of those complainants who filed complaints and determines liabilities of the tax assessees against whom such an application/complaint is made / received. Therefore, according to them, since the exercise of power by NAA is a quasi-judicial function, the absence of a judicial member in the constitution of NAA renders Section 171 of the Act, 2017 and Rule 122 of the Rules, 2017 illegal and void. In support of their submissions, they relied on the decision of the Supreme Court in Madras Bar Association v. Union of India, (2015) 8 SCC 583, Madras Bar Association v. Union of India, (2010) 11 SCC 1 and Chandra Kumar v. Union of India, (1997) 3 SCC 261.

26. They further submitted that in case of equality of votes amongst the members of NAA, the Chairperson has a second or casting vote, which renders Rule 134(2) illegal and unconstitutional.

27. Learned counsel for the petitioner in P.(C) 12647/2018 stated that the report issued by DGAP and the order passed by NAA in its case were barred by limitation as provided under Rule 133 of the Rules, 2017. He submitted that Rule 133 uses the word “shall” and thus mandates that NAA must determine and pass an order within a period of three months (prior to amendment dated 28th June, 2019) from date of receipt of the report from DGAP. He further submitted that the procedure that has been prescribed under the Rule 129(6) ought to have been strictly followed by the DGAP while investigating other products. He pointed out that in the case of the petitioner in W.P.(C) 12647/2018, Rule 129(6) of the Rules, 2017 as on 25th September, 2018 (the date on which NAA passed its order directing the DGAP to conduct investigation on the amount allegedly profiteered by the petitioner) or 30th October, 2018 (the date when the notice was issued by DGAP) mandatorily provided that DGAP was required to complete its investigation within three months. However, the report was submitted on 30th September, 2019 which is beyond the prescribed limitation period and thus, the same was without jurisdiction. He submitted that at the time the proceedings were initiated by NAA, Rule 129(6) of the Rules, 2017 mandated that the DGAP “shall” submit its report to NAA within three months which could be further extended to six months. Such time period was subsequently extended to six months vide Notification No. 31/2019 dated 28th June, 2019 which could be further extended to nine months. However, the impugned order is barred by limitation even if period is taken as six months as applicable from 28th June, 2019.

28. Learned counsel for the petitioners submitted that under Rule 133(3) of the Rules, 2017, NAA does not have any power or authority in law to pass an order in relation to any product, other than the product against which complaint has been received by the authorities. They submitted that till 28th June, 2019 (when Rule 133(5) was enacted), NAA had no powers to direct investigation in respect of any product, other than the product complained of. However, with effect from 28th June, 2019, Rule 133(5) was introduced, whereby for the first time, NAA was statutorily empowered in the course of the proceedings before it, to direct the DGAP, to conduct an investigation in relation to products, other than the product complained of. They submitted that as a result of the amendment, the power to expand the scope of the investigation vests only with NAA and not with DGAP. They pointed out that in many cases, DGAP had on its own expanded the scope of the investigation to other products, which according to them, is without jurisdiction and ultra vires the provisions of the Act, 2017 and Rules, 2017.

29. Learned counsel for the petitioners submitted that the levy of penalty and interest cannot be ordered in the absence of corresponding specific substantive provisions under the Act, 2017. They submitted that the consequences of the breach of Section 171 of Act, 2017 should have been provided for in the first instance in the Act, 2017 itself and such wide and uncontrolled powers could not have been conferred on NAA under Rules 127 and 133 of Rules, 2017. In support of their submission, they relied upon the judgments of the Supreme Court in Indian Carbon Limited State of Assam (1997) 6 SCC 479 and Shree Bhagwati Steel Rolling Mills v. CCE 2015 (326) E.L.T. 209 (SC).

30.They stated that the petitioners have been issued show cause notices directing them to explain why penalty prescribed under Section 171(3A) of the Act, 2017 read with Rule 133 (3) (d) of the Rules, 2017 should not be imposed upon them. They, however, submitted that Section 171 (3A) has been inserted in the Act, 2017 under Section 112 of the Finance Act, 2019 which came into force only from 01st January, 2020 and so penalty under the aforesaid Section could not have been imposed on the petitioners retrospectively.

31. Learned senior counsel for the petitioner in P.(C) 1171/2020 submitted that on a plain reading of Section 171(1) with Section 2(108) of the Act, 2017, it is clear that it applies to a reduction in the rate of Goods and Services Tax levied on a particular commodity or a grant of Input Tax Credit under the Act, 2017. He stated that the term ‘tax on any supply of goods or services’ and Input Tax Credit in Section 171 do not refer to any tax levied prior to 1st July, 2017 or to any Input Tax Credit granted under any such prior statute. Therefore, according to him, Section 171(1) of the Act, 2017 does not contemplate a comparison of the taxes levied after the introduction of the Act, 2017 with a basket of distinct indirect taxes applicable on goods and services before the operation of the Act. He stated that the indirect taxes levied on goods and services prior to July, 2017 by the States such as the VAT/Sales-tax, Octroi duty and Entry tax varied widely from State to State and often from area to area within a State. He stated that as a result, it is impossible to make any meaningful comparison between the rates of the pre- Goods and Services Tax taxes with the rates of tax levied under the Goods and Services Tax regime.

32. According to him, Section 171 of the Act, 2017 only permits a comparison between two single rates and not a comparison between one single tax rate (Goods and Services Tax) and a basket or combination of several other tax rates (pre-Goods and Services Tax indirect taxes). He submitted that Sections 2(62) and 2(63) of the Act, 2017 make it clear that the benefit of Input Tax Credits referred to in Section 171(1) are the Input Tax Credit granted under the Act, 2017 and not the Input Tax Credits granted under the Central Excise Act, the Service- Tax statute or the Sales-tax Acts. He further submitted that Section 9 of the Act, 2017 which provides for the levy of ‘a tax called the central goods and services tax on all intra-State supplies of goods or services or both…’ uses the same language as Section 171 and therefore Section 171 refers only to a reduction in the rate of tax levied / referred to under Section 9 of the Act,

33. Learned senior counsel for the petitioners in P.(C) 2897/2021, submitted that in a contract made after the reduction in the tax rate has come into effect, the parties are free to agree on any price. In support of his submission, he relied on Section 64-A of the Sale of Goods Act, which reads as under:-

“64A. In contracts of sale, amount of increased or decreased taxes to be added or deducted.—

(1) Unless a different intention appears from the terms of the contract, in the event of any tax of the nature described in sub-section (2) being imposed, increased, decreased or remitted in respect of any goods after the making of any contract for the sale or purchase of such goods without stipulation as to the payment of tax where tax was not chargeable at the time of the making of the contract, or for the sale or purchase of such goods tax-paid where tax was chargeable at that time,—

(a) if such imposition or increase so takes effect that the tax or increased tax, as the case may be, or any part of such tax is paid or is payable, the seller may add so much to the contract price as will be equivalent to the amount paid or payable in respect of such tax or increase of tax, and he shall be entitled to be paid and to sue for and recover such addition; and

(b) if such decrease or remission so takes effect that the decreased tax only, or no tax, as the case may be, is paid or is payable, the buyer may deduct so much from the contract price as will be equivalent to the decrease of tax or remitted tax, and he shall not be liable to pay, or be sued for, or in respect of, such deduction.

(2) The provisions of sub-section (1) apply to the following taxes, namely:—

(a) any duty of customs or excise on goods;

(b) any tax on the sale or purchase of goods.”

34.Learned counsel for the petitioner in P.(C) 2785/2021 submitted that as per Section 171(2) read with Section 2(80) of the Act, 2017, the authority (empowered to examine whether there has been commensurate reduction in price) has to be constituted by way of a duly gazetted notification and as per Section 166 of the Act, 2017, such notification has to be laid before the Parliament. He stated that contrary to these requirements, NAA had been constituted vide an administrative order No.343/2017 dated 28th November, 2017. He stated that Rule 122 of the Rules, 2017 has been notified and gazetted vide Notification No. 10/2017-Central Tax dated 28th June, 2017, which, at first blush, suggests that NAA had been constituted thereunder. However, on a closer analysis, it is clear that the said Rule cannot be said to be the fountainhead of constitution of NAA as Rule 122 essentially provides for composition of NAA and not for the constitution of NAA, even though the heading of the Rule is couched to suggest that the same apparently constitutes NAA. He submitted that if the said Rule (which was notified on 28th June, 2017) was indeed the fountainhead of constitution of NAA, the same would go against the very understanding of the respondents as recorded in the 35th and 45th Goods and Services Tax Council Minutes of Meeting as well as the Memo dated 09th September, 2019 of the Department of Revenue, Ministry of Finance, wherein it has been specifically observed that NAA had been constituted vide an office order dated 28th November, 2017.

ARGUMENTS ON BEHALF OF THE RESPONDENTS

35. Zoheb Hossain, learned counsel appearing on behalf of the Respondent-authorities, prefaced his submissions by stating that Parliament introduced the Act, 2017 in order to simplify and harmonise the indirect taxes regime in the country by eliminating the multiplicity of taxes that were levied on the same supply system as a result of which there was a cascading effect.

36. According to him, the “anti-profiteering” measures were introduced in the Goods and Services Tax regime in order to provide for a mechanism to ensure that the full benefits of input tax credits and reduced Goods and Services Tax rates flow to the consumers who bear the burden of tax and to prevent the suppliers from appropriating these benefits for themselves. He contended that anti-profiteering provisions under the Act, 2017 and the Rules, 2017 have been brought into force in the interest of consumer welfare and so any interpretation of the same must be in favour of the consumer.

37. He stated that the provisions essentially create a substantive restriction on the suppliers from appropriating the benefits of the Goods and Services Tax regime which may either be in the form of reduction in the tax rate effected pursuant to a decision of the Goods and Services Tax Council or in the form of benefit of Input Tax Credit which was unavailable under the earlier regime. He stated that correspondingly a substantive right has been created in favour of consumers to receive the benefit of reduction in rates and benefit of Input Tax Credit. He stated that in considering the constitutional vires of such a provision, the larger public welfare intended to accrue from the provision ought to be taken into consideration. He relied upon the decision of the Supreme Court in Pioneer Urban Land and Infrastructure Ltd. vs. Union of India, (2019) 8 SCC 416, wherein the Supreme Court examined a challenge to the amendments to the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016. He stated that in the aforesaid case the fact that the impugned provisions were part of a beneficial legislation was treated as an important factor in order to uphold the provisions.

38. He further submitted that Section 171 of the Act, 2017 has been enacted in furtherance of the goals of redistributive justice contained in the Directive Principles of State policy in Articles 38, 39(b) and 39(c) of the Constitution of The relevant portion of Articles 38, 39(b) and 39(c) are reproduced hereinbelow:-

“Article 38 – State to secure a social order for the promotion of welfare of the people

(1) The State shall strive to promote the welfare of the people by securing and protecting as effectively as it may a social order in which justice, social, economic and political, shall inform all the institutions of the national life.

Article 39 – Certain principles of policy to be followed by the State

The State shall, in particular, direct its policy towards securing—

. . .

(a) that the ownership and control of the material resources of the community are so distributed as best to sub serve the common good;

(b) that the operation of the economic system does not result in the concentration of wealth and means of production to the common detriment;”

(emphasis supplied)

39. He submitted that the scope of judicial review in a fiscal statute is fairly limited as laid down by the Supreme Court in multiple judgments such as State of M.P. v. Rakesh Kohli, (2012) 6 SCC 312 and R. K. Garg v. Union of India, 1981 (4) SCC 675.

40. He further submitted that Article 246A of the Constitution of India empowers the Legislature to make laws ‘with respect to’ Goods and Services Article 246A of the Constitution reads as under:-

“246A. Special provision with respect to goods and services tax.—

(1) Notwithstanding anything contained in articles 246 and 254, Parliament, and, subject to clause (2), the Legislature of every State, have power to make laws with respect to goods and services tax imposed by the Union or by such State.

(2) Parliament has exclusive power to make laws with respect to goods and services tax where the supply of goods, or of services, or both takes place in the course of inter-State trade or commerce.

Explanation.—The provisions of this article, shall, in respect of goods and services tax referred to in clause (5) of article 279A, take effect from the date recommended by the Goods and Services Tax Council.”

41. He submitted that the impugned Section 171 of the Act, 2017 does not violate Article 246A of the Constitution of India as the said Section is not a taxing provision but is only meant to ensure that the sacrifice of tax revenue by the Central and State Governments for the welfare of the consumer is passed on to them by the supplier.

42. He stated that the reduction of the tax burden and elimination of the cascading effect of taxes were important objectives behind the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax and so the impugned Section 171 of the Act, 2017 is very much a provision ‘with respect to’ Goods and Services Tax and, therefore, Section 171 of the Act, 2017 falls well within the ambit of law-making powers of the Parliament and the State He further submitted that it is a well settled principle that in the field of taxation, the legislature enjoys a greater latitude for classification as has been noted by the Supreme Court in various cases [See: Steelworth Ltd. vs. State of Assam [1962] Supp (2) SCR 589]; Gopal Narain vs. State of U.P. [AIR 1964 SC 370]; Ganga Sugar Corp. Ltd. vs. State of U.P. [(1980) 1 SCC 223].

43. Countering the submissions of the Petitioners that Section 171 of the Act, 2017 suffers from the vice of excessive delegation, Mr. Zoheb Hossain, learned counsel, submitted that no essential legislative function has been delegated by the Legislature to NAA by way of Section 171 of the Act, 2017. He stated that Section 171 of the Act, 2017 is very clear when it states that any reduction in the rate of tax or the benefit of input tax credit has to be passed on to the recipient by way of commensurate reduction in prices, that is to say that every person who is a recipient of goods or services has to get the He further stated that it cannot be said that Section 171 of the Act, 2017 does not provide method and procedure for determining profiteering as it clearly stipulates that ‘any reduction’ in the rate of tax on ‘any supply of goods or services’ or the benefit of input tax credit shall be passed on to the recipient by way of ‘commensurate reduction in prices’.

44. He emphatically denied that the word ‘commensurate’ as used in Section 171 of the Act, 2017 has no clear and definite meaning. He referred to the Cambridge Dictionary where the word ‘commensurate’ is defined as ‘in a correct and suitable amount compared to something else; suitable in amount or quality compared to something else; matching in degree’. Thus, according to him, Section 171 lays down a clear legislative policy and hence, no essential legislative function has been delegated. He submitted that the Courts have consistently held that after laying down the broad legislative policy, the minutiae can always be left to be decided by way of a subordinate legislation (See: Lohia Machines Ltd. vs. Union of India, (1985) 2 SCC 197, Pt. Banarsi Das Bhanot vs. State of Madhya Pradesh, AIR 1958 SC 909, Sita Ram Bishambher Dayal vs. State of U.P. (1972) 4 SCC 485). He further stated that it is well settled that the question whether any particular legislation suffers from excessive delegation, has to be determined by the Court having regard to the subject matter, the scheme, the provisions of the statute including its preamble and the background on which the statute is enacted. In support of his contentions, he relied upon the decision of the Supreme Court in Bhatnagars & Co. Ltd. vs. Union of India, AIR 1957 SC 478 and Mohmedalli and Ors. vs. Union of India and Ors., AIR 1964 SC 980.

45. He further submitted that power of NAA to determine procedure and methodology flows from Section 171 of the Act, 2017 itself which empowers the Authority to examine whether Input Tax Credits availed by any registered person or the reduction in the tax rate on the goods or services had actually resulted in commensurate reduction in the price of such goods or services. He stated that the rule-making powers of the Central Government as prescribed in sub section (2) of Section 171 of the Act, 2017 as well as Section 164 of the Act, 2017 empower the Central Government to prescribe the powers and functions of the authority as well as to prescribe a Rule conferring the Authority with the power to determine the methodology for determining whether the benefits of Goods and Services Tax rate reductions and Input Tax Credits have been passed on. According to him, it is in this background that the power to prescribe the powers and functions of NAA was delegated to the Central Government by the Section. He, therefore, submitted that the principle delegatus non potest delegare is not applicable to the present batch of matters.

46. He stated that Section 171(3) of the Act, 2017 duly provides that the Authority shall exercise such powers and discharge such functions as may be Accordingly, he stated that the Goods and Services Tax Council which is a federal, constitutional body, comprising all the Finance Ministers of all the States and UTs and the Union Finance Minister, in its due wisdom, and the Central and the State Governments have framed Rules 127 and 133 which prescribe the functions and powers of the Authority. He pointed out that these rules have been framed under the provisions of Section 164 of the Act, 2017 which also has sanction of the Parliament and the State Legislatures. Therefore, since the functions and powers to be exercised by the Authority have been approved by competent legislatures, the same are legal and binding on the Petitioners. In support of his submissions, he relied on the decision of the Supreme Court in M.K. Papiah vs. Excise Commr. (1975) 1 SCC 492.

47. Mr. Zoheb Hossain, learned counsel stated that even if the petitioners’ contention that no methodology for calculating the profiteered amount had been prescribed is accepted, then also the said Section will not be rendered unconstitutional because as per Rule 126 of the Rules, 2017, NAA has been empowered to determine the said methodology. He pointed out that the Rule does not stipulate that NAA must necessarily determine the methodology and procedure to compute profiteering as it merely stipulates that the authority ‘may’ determine the methodology and procedure for such computation. He stated that substantive provision of Section 171 of the Act, 2017 provides sufficient guidance to the NAA to determine the methodology on a case to case basis depending on the peculiar facts of each case and the nature of the industry and its peculiarities.

48. Additionally he stated that no uniform calculation method can be prescribed because the computation of commensurate reduction in prices is purely a mathematical exercise and would vary from SKU to SKU or unit to unit or service to service and hence for determining the quantum of benefit as the extent of profiteering has to be arrived at on a case to case basis, by adopting suitable method based on the nature and facts of each case. He further stated that NAA in exercise of the powers conferred under Rule 126 of the Central Goods and Services Tax has notified the “National Anti-Profiteering Authority: Methodology and Procedure, 2018” dated 28th March, 2018 which contains the methodology and procedure for determination as to whether the reduction in the rate of tax on supply of goods or services or the benefit of Input Tax Credit has been passed on by the registered person to the recipient by way of commensurate reduction in

49. In the context of the real estate sector, he stated that in cases where completion certificate had not been issued prior to 01st July, 2017 and the supply of service by the developer continued past 01st July, 2017, the supplier got the benefit of Input Tax Credits under the Goods and Services Tax That being the case, there is no reason why a supplier ought not to be required to pass on the benefit of Input Tax Credits under the Goods and Services Tax regime, with respect to the remaining supply. According to him, a plain reading of Section 171 of the Act, 2017 would require such developers to pass on the benefit of Input Tax Credits.

50. He stated that Section 171 of the Act, 2017 when it uses the term ‘any supply’ refers to each taxable supply made to each recipient thereby clearly indicating that netting off of the benefit of tax reduction by any supplier is not Hence, according to him, this benefit has to be calculated for the SKU of every product and has to be passed on to every buyer of such SKU. These benefits, he stated cannot be passed on at the entity/organization/branch/invoice/ product/business vertical level as they have to be passed on to each and every buyer at each SKU/unit/service level by treating them equally. Additionally, he stated that the language of the impugned provisions does not provide flexibility to adopt any other mode for transferring benefit of reduction in tax rate and benefit of Input Tax Credit. He, thus, stated that the Methodology & Procedure for passing on the benefits and for computation of the profiteered amount has been duly prescribed in Section 171 of the Act, 2017 itself and hence, it is not required to be prescribed separately.

51. He stated that in the case of reduction in the rate of tax, the quantum of benefit would depend upon the pre reduction base price of the product which is required to be maintained during the post rate reduction period on which the reduced rate of tax is required to be charged which would result in reduction in the price. According to him, the new MRP is required to be declared by affixing additional sticker or stamping or online printing in terms of letter WM/10(31)/2017 dated 16th November, 2017 issued by the Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution, Government of India.

52. While dealing with the argument of the Petitioners that it is legally impossible to pass on the benefits of the reduction of rate of tax in cases of low priced products in the FMCG industry, Zoheb Hossain, learned counsel, submitted that the Rules 2(m) and 6(1)(e) of Legal Metrology (Packaged Commodities) Rules, 2011 (as amended from time to time) provide guidance to the suppliers on how the MRP of the products is to be rounded off. The relevant portion of the aforesaid Rules are reproduced as hereinunder:-

“Legal Metrology (Packaged Commodities) Rules, 2011 dated 7th March, 2011 as enacted with effect from 1st April, 2011:

“2. Definitions:-

…..

(m) “retail sale price” means the maximum price at which the commodity in packaged form may be sold to the consumer and the price shall be printed on the package in the manner given below; ‘Maximum or Max. retail price Rs/ …….inclusive of all taxes or in the form MRP Rs/ ………incl., of all taxes after taking into account the fraction of less than fifty paisa to be rounded off to the preceding rupees and fraction of above 50 paise and up to 95 paise to the rounded off to fifty paise;

xxx xxx xxx

6. Declarations to be made on every package. –

(1) Every package shall bear thereon or on the label securely affixed thereto, a definite, plain and conspicuous declaration made in accordance with the provisions of this chapter as, to –

….

(e) the retail sale price of the package; Provided that for packages containing alcoholic beverages or spirituous liquor, the State Excise Laws and the rules made there under shall be applicable within the State in which it is manufactured and where the state excise laws and rules made there under do not provide for declaration of retail sale price, the provisions of these rules shall apply.”

Legal Metrology (Packaged Commodities) Rules, 2011 as amended by the Legal Metrology (Packaged Commodities) Amendment Rules, 2017 with effect from 1st January, 2018:

2. Definitions:-

‘(m) “retail sale price” means the maximum price at which the commodity in packaged form may be sold to the consumer inclusive of all taxes;’;

xxx xxx xxx

4. In the said rules, in rule 6,-

(d) in clause (e), after the words “the retail sale price of the package;”, the following words and figures shall be inserted, namely:- “shall clearly indicate that it is the maximum retail price inclusive of all taxes and the price in rupees and paise be rounded off to the nearest rupee or 50 paise;………………………………………. ”

53. He agreed with the contention of the petitioners that in some cases, commercial factors might necessitate an increase in price despite reduction in rate of tax or availability of benefit of Input Tax Credits. However, he stated that the prices must not be increased to appropriate the benefit of the reduced tax rate or benefit of additional Input Tax Credit that accrues to the Petitioners. According to him, if the supplier never passed on the benefit of such reduced tax rate or Input Tax Credit by way of a commensurate reduction in prices of the goods or services, by increasing the base price of such goods or services, he would be depriving the recipients of the benefits of the reduction of tax rates or Input Tax Credits. Hence, he stated that if the supplier when increasing the base prices of the goods or services does not account for the (commensurate) reduction of prices as a result of the reduction of the tax rates or benefit of the Input Tax Credits, the supplier would be said to be profiteering under Section 171 of the Act, 2017. He, however, stated that NAA as well as this Court ought to be cautious of attempts of entities to justify suspicious increase in base prices contemporaneous with the reduction in tax rates or accruing of benefits of Input Tax Credits, under the garb of other commercial factors. According to him, the Courts and implementing authorities must be vigilant about devices designed for avoidance and must seek to adopt interpretations of the provisions that are least prone to resulting in avoidance. He referred to the judgment in McDowell & Co. Ltd. v. CTO, (1985) 3 SCC 230 where it has been held that “the proper way to construe a taxing statute, while considering a device to avoid tax, is not to ask whether the provisions should be construed literally or liberally, nor whether the transaction is not unreal and not prohibited by the statute, but whether the transaction is a device to avoid tax, and whether the transaction is such that the judicial process may accord its approval to it” and that “it is up to the Court to take stock to determine the nature of the new and sophisticated legal devices to avoid tax and consider whether the situation created by the devices could be related to the existing legislation with the aid of “emerging” techniques of interpretation.” He submitted that although the aforesaid findings were made in the context of tax avoidance, they would apply with equal force in the context of any beneficial legislation.

54. Mr. Zoheb Hossain, learned counsel further stated that reference made by the petitioners to guidelines under other laws and to certain foreign laws, is irrelevant to the issue of the constitutional validity of Section 171 of the Act, 2017 as validity has to be determined on its own merits.

55. He further stated that according to petitioners’ own submissions the anti- profiteering provisions introduced in Australia and Malaysia were essentially price control mechanisms as the legislation enacted in Australia was aimed at prohibiting ‘price exploitation’ and the Act enacted in Malaysia was aimed at prohibiting manufacturers from ‘making unreasonably high profits’.

56. He stated that Section 171 of the Act, 2017 is not a price-fixing provision as was sought to be asserted by the Petitioners. He submitted that Section 171 of the Act, 2017 only concerns itself with the indirect-tax component of the price of goods and services and does not impinge upon the freedom of suppliers to fix prices of their goods and services keeping in view relevant commercial and economic factors. He stated that the impugned section in pith and substance is a provision pertaining to the Goods and Services Tax and through its enactment the Parliament sought to ensure that the businesses pass on the benefits granted by the Government in term of reduction of tax rate and availability of Input Tax Credit to the consumers and does not seek to interfere with the right to trade by fixing the price at which the goods and services ought to be supplied. He pointed out that the impugned provision applies irrespective of the price of the goods or He stated that it cannot be said that a law which forbids recovery of Goods and Services Tax at a rate higher than that applicable on the goods and services and which forbids suppliers from recovering Input Taxes from the recipients where credits are obtained on such Input Taxes, amounts to price- control or price-fixing.

57. He further submitted that even if Section 171 of the Act, 2017 is presumed to be a price-fixing legislation, it would not render the Section violative of Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution of India. He submitted that the Supreme Court in several cases such as Diwan General and Sugar Mills Pvt. Ltd. & Ors. vs. Union of India, AIR (1959) SC 626; Union of India vs. Cynamide India Ltd., (1987) 2 SCC 720 where price fixing orders had been challenged, had upheld such orders by examining whether the orders take into account relevant factors/considerations.

58. He submitted that there is no legal principle on the basis of which the petitioners can contend that the mere absence of a time period, up to which reduced prices are required to be maintained, would render the provision unconstitutional.

59. He submitted that recently, a three-Judge Bench of the Supreme Court in Madras Bar Association v. Union of India & Anr., (2021) SCC OnLine SC 463, while considering the challenge to the vires of Tribunal Reforms (Rationalisation and Conditions of Service) Ordinance, 2021 and Sections 184 and 186(2) of the Finance Act, 2017 as amended by the Tribunal Reforms (Rationalisation and Conditions of Service) Ordinance, 2021, held that “the apprehensions of misuse of a statutory provision is not a ground to declare the provisions of a statute as void.”

60. Mr. Zoheb Hossain, learned counsel, submitted that for an appeal to be maintainable, it must have its genesis in the authority of law [See: M. Ramnarain (P) Ltd. v. State Trading Corpn. of India Ltd. [(1983) 3 SCC 75 and Gujarat Agro Industries Co. Ltd. v. Municipal Corpn. of the City of Ahmedabad (1999) 4 SCC 468]. He submitted that the principle of “appeal being a statutory right and no party having a right to file appeal except in accordance with the prescribed procedure” is now well settled as held by the Supreme Court in CCI v. SAIL, (2010) 10 SCC 744. According to him, the right to appeal is not a right which can be assumed by logical analysis much less by exercise of inherent jurisdiction. It essentially should be provided by the law in force. In the absence of any specific provision creating a right in a party to file an appeal, such right can neither be assumed nor inferred in favour of the party.

61. He stated that Section 171(2) of the Act, 2017 lays down the role of NAA which is to examine whether Input Tax Credit availed by any registered person and/or the reduction in tax rates have actually resulted in a commensurate reduction in the price of goods or services supplied by him and the duties of NAA have been further elaborated upon in Rule 127 of the Rules, 2017. He further stated that from a perusal of the aforesaid provision, it is clear that the functions of NAA are in the nature of a fact-finding exercise. He submitted that even if it is assumed that the Authority undertakes an exercise which determines the rights and liabilities of registered persons under the Act, the contention of the Petitioners that the absence of a judicial member in NAA renders the authority unconstitutional is not tenable as there is no universal principle that every quasi- judicial authority at every level must have a judicial member. According to him, such a requirement would not only be wholly impractical but also be legally He stated that the judgments which have been relied upon by the petitioners follow a uniform principle that whenever a judicial tribunal is intended to replace or supplant the High Court with respect to judicial power which was hitherto vested in or exercised by Courts, such Tribunals must be manned by judicial members in addition to technical members who have specialized knowledge or expertise in a given field. In support of his submissions, he relied on the judgments of the Supreme Court in Union of India vs. R. Gandhi, (2010) 11 SCC 1, Rojer Mathews vs. South Indian Bank, (2019) SCC OnLine SC 1456. He stated: (a) the NAA did not replace or substitute any function which Courts were exercising hitherto; (b) it performs quasi-judicial functions but cannot be equated with a judicial tribunal; (c) it performs its functions in a fair and reasonable manner in accordance with the Act but does not have the trappings of a Court and (d) absence of a judicial member does not render the constitution of the NAA unconstitutional or legally invalid.

62. He further stated that there are several statutory bodies that exercise quasi- judicial functions, but are not required to have judicial members. For example, Section 4(1) of the Securities and Exchange Board of India Act, 1992 which provides for the composition of the Securities and Exchange Board of India (‘SEBI’), does not necessarily require the presence of Judicial Members in SEBI. He pointed out that the fact that the SEBI inter-alia performs judicial functions has been recognized by the Supreme Court in Clariant International Ltd. & Anr. Securities and Exchange Board of India (2004) 8 SCC 524. Similarly, he stated that Telecom Regulatory Authority of India, Medical Council of India, Institute of Chartered Accountants of India and the Assessing Officers, CIT (Appeals), Dispute Resolution Panel under the Income Tax Act perform quasi- judicial functions but there is no requirement that such members must possess either a law degree or have had judicial experience.

63. He submitted that a casting vote in the hands of the chairperson is a fair and reasonable manner of deciding a tie in votes and is commonly provided for in several laws.

64. He stated that NAA has been constituted as per the provisions of Rule 122 of the Rules, 2017. The Rules, 2017, including Rule 122, have been duly notified by the Ministry of Finance, Department of Revenue, Central Board of Indirect Taxes & Customs vide Notification 3/2017- Central Tax dated 19th June, 2017 and published in the Gazette of India- Extraordinary vide G.S.R. No. 610(E) on the same date and hence NAA has been duly constituted by a Notification as required under Section 171(2) of the Act, 2017. The above notification dated 19th June, 2017 was laid before the Lok Sabha on 11th August, 2017 and before the Rajya Sabha on 08th August, 2017 as required by Section 166 of the Act, 2017.

65. He submitted that in the absence of an express provision to the effect that anti-profiteering proceedings would abate if time-lines are not strictly adhered to, and if the time-lines are read to be mandatory, it would result in gross injustice to the consumers who would be left remediless on account of no fault of theirs.

66. Further, in the absence of anything to the contrary in the amendment or the amended provision, on a plain reading of the provision, the amended/extended time-period for passing of an order would apply to all pending and future proceedings before NAA. He submitted that the time-frames provided in the anti- profiteering provisions are merely directory in nature and not mandatory.

67. Zoheb Hossain, learned counsel, stated that Section 171 of the Act, 2017 is widely worded and does not limit the scope of examination to only the goods and services in respect of which a complaint is received by the authorities. He submitted that Rule 129 of the Rules, 2017, which provides for the scope of powers of the DGAP, uses the words ‘any supply of goods or services’ and so the scope of powers of DGAP is very wide.

68. He stated that the contention of the petitioners that there was no mechanism for recovery of the alleged profiteered amount under Section 171 of the Act, 2017 overlooks Rule 133(3)(b) of the Rules, 2017 prescribed under Section 171(3) of the Act, 2017 which empowers NAA to order a supplier to return to the recipient, an amount equivalent to the amount not passed on by way of commensurate reduction in prices along with interest at the rate of eighteen per cent [18%] from the date of collection of the higher amount till the date of the return of such amount or recovery of the amount not returned including interest, as the case may be.

69. Mr. Zoheb Hossain, learned counsel, submitted that the judgments of Supreme Court in Indian Carbon Ltd. Vs. State of Assam, (1997) 6 SCC 479 and Shree Bhagwati Steel Rolling Mills vs. CCE (2016) 3 SCC 643 etc. relied upon by the petitioners were delivered in the context of considering the question of whether interest can be levied for delayed payment of tax and whether penalty can be imposed for non-payment of tax under a Rule where the Statute does not authorize the same.

70. He submitted that by virtue of Rule 133(3)(d) of the Rules, 2017, NAA was already vested with the powers to impose penalties even before Section 171(3A) came into force. According to him, Section 171(3A) of the Act, 2017 is therefore merely clarificatory in nature. He further submitted that in the absence of a power to impose penalties, there would be no consequence arising out of the violation of Section 171(1) of the Act, 2017 by suppliers and consequently, there would be no deterrence against non-compliance.

71. Even otherwise, he stated that show cause notices initiating penalty proceedings in relation to violation of Section 171(1) prior to the coming into force of Section 171(3A) of the Act, 2017, have been withdrawn by NAA and penalty proceedings in all such cases are not being pressed and so this issue has become Insofar as the objection regarding levy of interest is concerned, he submitted that the object of the anti-profiteering measures provided in Section 171 of the Act, 2017 is to ensure that the Input Tax Credits availed by any registered person or the reduction in tax rate result in a commensurate reduction in the price of goods or services or both supplied by him and as a result, the benefit of the same passed on to the recipients. He stated that the profiteered amount includes the benefit of reduction in taxes or Input Tax Credits which was required to be passed on by way of reduction in prices as well as the tax thereon which the consumer is forced to pay as a result of the non-reduction of prices as required under Section 171(1) of the Act, 2017. He emphasised that had the supplier passed on the benefit of reduction in tax rates or Input Tax Credit by way of reduction in prices, the consumer would not have been required to pay the additional Goods and Services Tax.

72. Mr. Zoheb Hossain submitted that without prejudice to the fact that each and every Act of NAA is well reasoned and justified and can be defended to the satisfaction of this Court as and when the same are taken up case-wise, the case- specific submissions of the petitioners have no bearing whatsoever while considering the constitutional vires of Section 171 of the Act, 2017 and Rules contained in Chapter XV of the Rules, 2017.

ARGUMENTS ON BEHALF OF THE LEARNED AMICUS CURIAE

73. Amar Dave, learned Amicus Curiae stated that the cardinal objective with which the Goods and Services Tax had been introduced was inter alia to ensure an efficient and robust indirect taxing system.

74. He contended that a perusal of the reports and the discussions preceding the introduction of Goods and Services Tax regime clearly indicated that the impact on prices of various goods and services had been factored in as a necessary consequence of the shift over to the Goods and Services Tax regime.

75. He pointed out that the report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India (‘CAG’) of June, 2010 dealt with the manner in which the Value Added Tax (‘VAT’) was implemented in India and accordingly threw light on the lessons for transition to Goods and Services Tax. One of the elements covered in the said report was the impact that VAT had on prices of goods. The report found that the white paper at the time of introduction of VAT was sanguine that implementation of VAT would bring down the prices of goods due to rationalisation of tax rates and abolition of cascading effect of tax in the legacy However, on the examination and analysis of a small data survey, the CAG found that the manufacturers did not reduce the maximum retail prices after introduction of VAT even when there had been a substantial reduction in tax rates. It was, therefore, found that despite introduction of VAT and reduction in the tax rates, the benefits ensuing from such reduction were not passed on to the consumers by the manufacturers and the dealer networks across the VAT chain had enriched themselves at the cost of the common man. The report highlighted these aspects as those to be borne in mind at the time of considering the shift over to the Goods and Services Tax regime and to ensure mechanism for the purposes of passing on the benefit of tax rationalisation to the ultimate common man.

76. He stated that similarly, another report of the taskforce on Goods and Services Tax i.e. the 13th Finance Commission Report of 15th December, 2009 comprehensively dealt with minute aspects of the contemplated Goods and Services Tax ecosystem and various elements of such In its introduction, the report contemplated inter alia that the prevailing indirect tax system both at the Central and the State level included high import tariffs, excise duties and turnover tax on domestic goods and services having cascading effects, leading to a distorted structure of production, consumption and exports and this problem could be effectively addressed by shifting the tax burden from production and trade to final consumption. The report highlighted the implications of the switchover to Goods and Services Tax and the benefits that would entail from such a switchover. He pointed out that para 7.22 of the said report specifically recorded that the benefit to the poor from the implementation of Goods and Services Tax would flow from two sources, first through increase in the income levels and second through reduction in prices of goods consumed by them. It was specifically observed that the proposed switchover to the flawless Goods and Services Tax system should therefore be viewed as a pro-poor system and not regressive. The report further specifically went into the implications of the proposed switchover to Goods and Services Tax on various products and sectors including prices of the goods.