Soft food prices might have kept the lid on the RBI’s policy rates but it might be important to examine why the food basket’s price trends have been much weaker than what their usual seasonal patterns imply. This might help us grapple with some key questions:

- Will this weakness continue and offset pressure in other components?

- Does it represent a structural change in the agri sector that will permanently lubricate supply chains.

There is no doubt that supply management has improved over the last few years and the central government in collaboration with the states have played a key role in this. However the ‘excessive’ moderation in prices might be reflective of some other factors:

- Weak demand in the rural areas on account of low wage growth

- Distress selling in some agricultural items because of a supply glut.

Supply gluts are by their very nature temporary and the current excess supply could well swing to a supply shortfall by the middle of 2019. From an inflation perspective, this raises the likelihood of the dreaded worst case – rising fuel and food prices exerting sharp upward pressure on headline. However, if there is indeed a long term demand slowdown on the back of soft wages, a serious rethink on rekindling our wage guarantee and other income support schemes need to be considered.

Soft food prices might have kept the lid on the RBI’s policy rates but it might be important to examine why the food basket’s price trends have been much weaker than what their usual seasonal patterns imply. This might help us grapple with some key questions:

1) Will this weakness continue and offset pressure in other components?

2) Does it represent a structural change in the agri sector that will permanently lubricate supply chains.

There is no doubt that supply management has improved over the last few years and the central government in collaboration with states have played a key role in this. However the ‘excessive’ moderation in prices might be reflective of some other factors:

- Weak demand in the rural areas on account of low wage growth

- Distress selling in some agricultural items because of a supply glut.

Supply gluts are by their very nature temporary and the current excess supply could well swing to a supply shortfall by the middle of 2019. From an inflation perspective, this raises the likelihood of the dreaded worst case – rising fuel and food prices exerting sharp upward pressure on headline. However, if there is indeed a long term demand slowdown on the back of soft wages, a serious rethink on rekindling our wage guarantee and other income support schemes need to be considered. Read more for details!

Benign Inflation in India

A depreciating currency, rising current account deficit, concerns of a breach of the fiscal deficit target, earnings downgrades, and the lingering issue of NPAs in the financial sector –there has been no dearth of bad news on the economy. The saving grace has been ‘inflation’ in which the trend has been particularly comfortable.

At 4.3 per cent, average CPI inflation in the first half of this financial year (2018-19) has been pretty close to the central bank’s long term target of 4.0 per cent. Longer data trends should bring more cheer – the average rate in the last six years has been around 6.4 per cent (as per the new CPI series beginning January-2011).

Muted inflation in the past few months can largely be explained in terms of food prices. All other components of inflation (housing, fuel, clothing, tobacco, services etc.) have been either rising or remained broadly unchanged, be it on the back of rising fuel prices or adjustment in the HRA allowances of the government employees. Meanwhile, food inflation has been surprising on the downside for nine consecutive months.

If the trend in food inflation reverses, it could have some serious implications. For now, the government is facing a double whammy of rising fuel prices and depreciating rupee but this has been successfully countered by the extreme softness in agri-inflation. The damage to the economy could be much more if food prices also begin to rise. Therefore, we clearly need to understand the underlying risks and be ready for the worst.

What’s cooking with food?

One might argue that the decline in global food prices (7.5 per cent YoY for September- 2018) is depressing local prices. However, the correlation between Indian food prices and global food prices have always been very weak. For most of the agricultural commodities, domestic factors play a much more important role. For example, cost of production and MSP (Government policy of minimum support prices) are the main drivers for cereals, while inflation in vegetables, meat, and fish are largely driven by domestic input-cost factors. Global food prices only affect limited set of commoditized items like edible oil, milk and sugar.

Moreover, even if one might take into account the 7.5 per cent decline in global food prices over the past year as a major influence, it could have been entirely mitigated by around 11 per cent depreciation in the rupee during the same period.

Could policy induced structural changes in the national food market be other explanation? Launched in April-2016, unification of local mandis through a digital platform (electronic- national market, eNAM) has been the key initiative of the government in this regard. This was aimed at facilitating better price discovery, direct selling, avoiding black-marketing, and promoting transparency. However, the progress has been slow and the level of trading through the electronic portal has been below potential. In a country of around 130 million farmers, only 11 million farmers have registered on the eNAM platform (as of August- 2018). In terms of the trading activity, under eNAM, about 585 mandis with physical trade have been replaced by electronic trade in 14 states. However, only around 377 of those remain online.

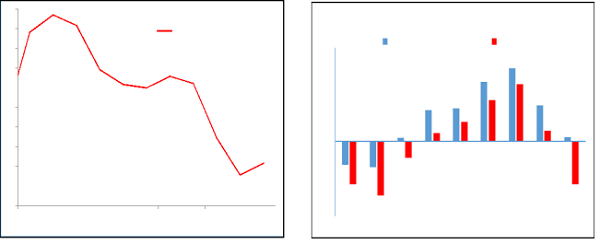

In our view, distress selling in response to temporary oversupply factors has been one of the key reasons for decline in food inflation. If we dig deep, the downside surprises in food inflation can largely be attributed to four components, vis-à-vis vegetables, sugar, pulses, and milk.

Chart 1: Decline in food inflation

Source: CEIC and HDFC Bank

- In case of sugar (prices down 6.4 per cent CYTD), the world has gone from supply deficit to supply surplus in the past year or so. This is a typical of commodities and in the case of sugar the long term structural shift towards alternative sweeteners has weakened global demand. Meanwhile, supply from India and Thailand (top producers of sugar) have been in excess.

- Moreover, the problem in India is that sugarcane prices are decided by the government (centre and states) while sugar prices are determined more by demand and supply dynamics. Sugarcane prices have not been in sync with the demand for the final product sugar. Farmer’s decision to produce largely depend on timely payment by millers. In years in which sugar prices are high, sugar mills’ realizations improve with good prices and millers promptly pay farmers. As the farmers plant more sugarcane, sugar prices fall due to oversupply. In the next season, the mills are unable to pay farmers, and then, the farmers plant less. This cycle repeats A transparent cane pricing formula linked to mills’ realizationsǰencouraging farmers to move to other crops, and better understating of global demand dynamics are some policy interventions that are needed in this regard. However, until the overhaul of the sugar industry takes place, the volatility in sugar prices could continue. In a nutshell, the prices could normalize in the next few months (by the next season).

- As for the milk industry, the crisis lies primarily in the skimmed milk-powder The powdered variety is the main item of export for India, while most of the liquid variety is consumed domestically. In this regard, a slump in global prices of skimmed milk powder have hit Indian exports, resulting in a surplus domestic stockpile. Experts in this field point out that the average price of skimmed milk powder in the international market is around Rs 120 per kg, while the cost of production in India is at least Rs 200 per kg. Given that the commodity is highly perishable, the surplus is leading to distress selling and thus lower prices in the domestic market.

- What can be done about this? The dairy sector is among the few success stories of the cooperative model in India and a freeze on incomes in this sector cannot be It is most likely to force the government to intervene. Be it a large scale export push or increasing domestic demand by providing milk in welfare schemes (eg. Ksheera Bhagya scheme of Karnataka), it is highly likely that the milk market could also stabilize in the next few months.

- In the case of pulses (prices down 6 per cent on CYTD basis), high domestic production (government-supported prices for pulses have seen farmers shift from wheat to crops such as chickpeas) and rise in imports (from Canada etc.) have distorted the market dynamics. However, in response to the declining prices, the government has raised import taxes and restricted overseas purchases. While the support schemes have not helped reverse the trajectory so far, we believe that pick up in the procurement in the coming months and possible promotion of exports in this segment could help contain the price decline issue.

- Lastly, a bit on vegetable prices – down 7.2 per cent on CYTD basis. Out of the 19 items analysed by us, around 57 per cent of them have showcased a decline in inflation this year. Among these, tomatoes and onions are the heavyweights and explain the large part of the story.

- For tomatoes, an import ban from Pakistan (50 per cent of total tomato exports were to Pakistan alone) has tilted the balance in the market. Whereas for onions it is largely an issue of supply mismanagement. Enthused by last year’s good pricesǰmany farmers opted to grow onions this year, leading to a supply glut.

- The market for TOP crops (Tomato, onion, potato) in India is prone to large seasonal fluctuation in prices. Within a span of six months, the market can go from undersupply to oversupply, and vice-versa. It is likely that the onion farmers would adjust their supply by the next season, and similarly the tomato famers would take Pakistan’s import ban into account before sowing the next crop. Prices most likely could normalize by the next season.

Chart 2: Decline in Tomato and Onion inflation

Source: CEIC and HDFC Bank

- This is precisely why the government allocated funds for better management of supply in this sector in the form of Operation Greens in this year’s budget (with an outlay of Rs. 500 crore to address price volatility of perishable commodities like tomatoes, onions and potatoes). While it could take some time to reap the benefits of Operation Greens, in the short-term, the prices could be volatile.

The other important angle: Wages and rural slowdown

An important element in this regard is the impact on demand of specific food items as per capita income rises in the country. The Engel curve, a standard model in economics, describes how household expenditure on a particular good or service varies with household income. As income rises, proportion of income going to necessary goods declines and that of other commodities go up. For example, rise in rural incomes would lead to a shift in expenditure from traditional sources of protein to pulses and thus demand for pulses would rise in the country. A similar impact would play out in the urban areas where the shift would be towards pulses and also animal protein (eggs, meat etc.).

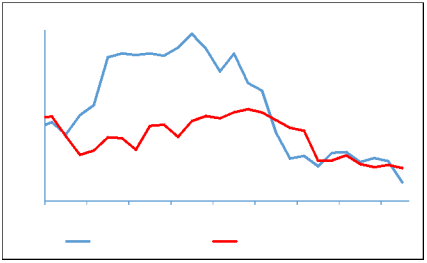

This shift in the pattern of consumption seemed to have reached an inflection in the mid-2000s and post that, rising demand for pulses and protein related items pushed overall food inflation higher leading to a major inflation scare.

What’s the situation now? In the context of the rural economy, while the agricultural output is rising, falling prices of agricultural commodities, from pulses, vegetables, and even livestock-output, has caused a decline in income and consequently lower demand for food, in turn pushing prices down further.

Chart 3: Protein inflation has come down drastically in the last two years

Source: CEIC and HDFC Bank. NB: Proxy measurJe based on Meat and Fish, Egg, Milk and Pulses

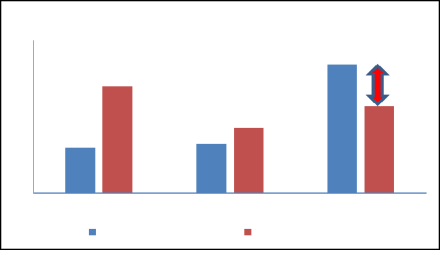

According to a RBI study there has been a “significant deceleration” in rural wages since 2014. A RBI working paperi, says that the growth in rural wages has recorded significant deceleration since 2014.

One may ask that why are rural wages crawling when farm GDP growth is growing at a reasonable pace. While there are multiple factors, the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Generation Scheme, which was a driving factor for rural wages, seems to have lost momentum in the recent years. The average number of employment days per household have declined from 48.9 in 2015-16 to 45.8 in 2017-18 and further to 33.5 so far in 2018-19.

Chart 4: Decline in rural wage growth

Source: CEIC and HDFC Bank. NB: Latest wage series starts from Nov-2013. In the older series, wage growth was recorded in double digits for 2014.

If there is squeeze in wages, this should be reflected in overall rural demand and consequently core inflation in rural areas is also likely to go down. Recent inflation data shows interesting results in this regard. The Core inflation gap between rural areas and urban areas has widened in FY19. In 2017-18, rural core inflation was largely in line with urban core inflation. This has widened to around 1 ppt so far in Fiscal year 2018-19ii.

4 Chart 5: Inflation differential – Rural vs. Urban

Source: CEIC and HDFC Bank

Rural indebtedness: Could it weigh on demand?

Most recent data in this regard is from NABARD’s all India Rural Financial Inclusion Survey, named ‘NAFIS’, published in August-2018.

- The survey was conducted between January 2017 and June 2017, covering 40,327 households in 245 districts spread across 29 states in India. NABARD found that 52.5 per cent of the agricultural households had an outstanding loan on the date of the survey, with an average debt of Rs. 104,602 for the indebted agricultural households.

- According to the survey, the average annual income of an agricultural household was Rs. 107,000, barely Rs. 2,500 more than the average outstanding debt of indebted farm households.

If we were to relate the indebtedness data with the wage growth statistics, one can argue that the debt problem in rural areas might have become more severe since the middle of last year. This is because, since mid-2017, the wage growth has been particularly low and thus the next round of survey results can possibly show further problems related to debt servicing for agricultural households.

This is also something which can help explain the boom in consumer spending and robust earning patterns for the FMCG companies in India. Sceptics often point out to the robust FMCG sales to argue against any idea of slowdown in rural India. However, for one, indebtedness data shows that the possibility of credit-driven-consumption cannot be dismissed, especially given the extraordinary lending pace of NBFCs and housing finance companies. Two, it is important to look at the breakup of the sales of FMCG companies. It is quite possible that upper income class in the rural areas are driving such sales (backed-up by credit from institutional sources) and low-end goods are not recoding robust growth rates.

Having said that, we await for the next round of survey results to draw concrete conclusions in this regard. On account of farm loan waivers, the situation might have improved in some states but the debt statistics at a national level is something we need to understand further.

Conclusion

In a nutshell, if prices go down because of better demand-supply management (foreseeing demand changes and adjusting crop-acreage patterns in advance), or because of decline in cost for the farmer or because of better warehousing capacities, or on account of increase in productivity in the farm sector, then the price declines are efficient and also last long. In India’s caseǰ food prices seem to be going down less on account of these factors and more so because of oversupply. In all likelihood it seems to be a short-term phenomenon.

At this stage it is difficult to say how much of price decline is because of slowdown in demand in the rural areas. If it is indeed that the compression of rural demand is a big factor, then it is certainly raises a red flag for growth and inequality. In short, it is difficult to categorize the ongoing decline in inflation entirely as a healthy trend.

Treasury Economic Research team

Disclaimer: This document has been prepared for your information only and does not constitute any offer/commitment to transact. Such an offer would be subject to contractual confirmations, satisfactory documentation and prevailing market conditions. Reasonable care has been taken to prepare this document. HDFC Bank and its employees do not accept any responsibility for action taken on the basis of this document

i RBI Working Paper No. 3/2018: Rural Wage Dynamics in India: What Role does Inflation Play?, 25th April, 2018

ii An important caveat here is that higher housing inflation might have pulled up the core inflation number for urban areas (because of adjustments in the HRA of government employees). However, even the recent reading for September, when housing inflation softened in the urban areas, showed that that the rural-core inflation was lower than the urban-core inflation. This is a cause for caution!