Introduction

With the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax (GST), the entire landscape of indirect taxation in India has undergone an upheaval. The GST has been hailed as a revolutionary enactment which would remove the cascading effect of taxes, i.e. no longer would tax on tax be have to be paid. To do this a seamless credit system has been formulated where any tax paid on any input service that is utilised during the process of developing a product or a service would have to be set-off against the subsequent output tax paid.

This would once fully implemented, substantially bring down the prices of goods and services. However, a worry of the government was whether the manufacturers and service providers would pass on the benefit of reduced prices to the final consumers. To ensure that the manufacturers and service providers do so, the government has put in place what is called an ‘anti-profiteering’ clause in the GST law. This has been done through Section 171 of the Central Goods and Services Act (“CGST”).[1]

This provision has generated great discussion and debate amongst consumers, businesses, and legal commentators. Through the course of this project we shall discuss the law on anti-profiteering as provided under the GST and its subsequent rules. Following this, we shall discuss both, how this mechanism can help consumers and businesses and the challenges it poses to businesses in India. After this, we will undertake a comparative analysis to examine how the Indian law on anti-profiteering compares with similar provisions in other jurisdictions such as Australia and Malaysia. Thereafter, we shall conclude by assessing what India can learn from the practice of these other countries, and what the way ahead would be in this regard.

Section 171 of CGST Act and Anti Profiteering Rules

The term profiteering means the act of making or seeking to make excessive or unfair profits in an illicit manner. Accordingly, as the name suggests, the anti-profiteering law under the GST prevent entities from making excessive profits due to implementation of the GST. To achieve this, Section 171 has been enacted under the CGST which makes it mandatory for manufacturers and service providers to pass on the benefit they have gained owing to

- Reduction in rate of tax; or

- Benefit of input tax credit;

to the consumer by way of commensurate reductions in prices.[2]

Through sub-clause (2) of Section 171, the central government has also been enabled to set up an Authority or authorise an existing Authority to monitor and enforce compliance with the requirements of the provision. To operationalise this clause, the GST council has issued the Anti-profiteering Rules 2017 [“APR 2017”].

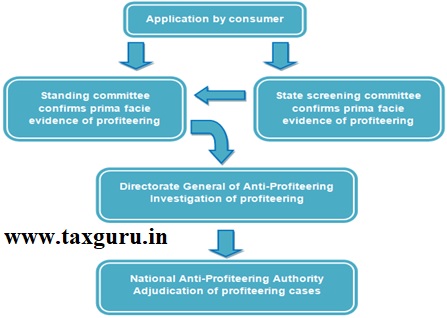

Under the APR Rules, the anti-profiteering structure is three-tiered, comprising a nine-member Standing Committee of the GST Council,[3] a director-general safeguards [“DG”] and a five-member Anti-Profiteering Authority Authority. Rule 3 of the APR 2017, provide for the appointment of a National Anti-Profiteering Authority (“Authority”), which shall be responsible to determine the method and procedure for determining whether the reduction in rate or the benefit of input tax credit has been passed on by the seller to the buyer by reducing the prices.[4]

To carry out this function the APR 2017, provide for a three-stage mechanism to deal with consumer complaints about profiteering practices of businesses. In the first stage, the Standing Committee receives the written complaints of profiteering practices and verifies the accuracy and adequacy of the evidence provided in the complaints. After reviewing the prima facie evidence to support the complaints, the committee forwards them to the DG for a detailed investigation. The second stage involves investigation of the complaints forwarded to the DG, which can take up to three months. In doing so, the DG could examine the balance sheets of companies to see if the price benefits of GST are passed on to consumers. In the final stage, the DGS submits the investigation report to the Authority, which will have three months to give its verdict.[5]

If the Authority finds a business to have committed anti-profiteering practices, in accordance with Rule 14 of the APR 2017, the Authority can initiate any of the following actions:

cancel the registration of the company;

- impose a penalty on the company;

- order a reduction in prices;

- order the company to refund the customer an amount equal to what it has earned by not passing on the price benefits from the time the GST took effect; or

- In case the buyer is not identifiable, order the company deposit the refund amount in the Consumer Welfare Fund.

Apart from the complaints received from the consumers, the Authority can also take suo motu action. Further, as per Rule 18, this anti-profiteering mechanism, as well as the authorities, will remain in force only for a period of two years.

The process for filing an anti-profiteering complaint is explained as follows:

Page Contents

Is there a Lacunae in the Anti Profiteering Law?

While it is true that the anti-profiteering law in India has been enacted with the noble intention of safeguarding the interests of consumers, it is not free of criticisms. In fact, there are numerous grounds on which the validity and effectiveness of this law can be questioned:

> There may be a constitutional challenge to the Anti-Profiteering Rules.

a. The APR 2017 may qualify as an instant of excess delegation

The Separation of power is a fundamental feature of the Indian Constitution, which means that the three wings – Judiciary, Legislature and Executive, cannot encroach upon one another’s domain.[6] As a result, while it is true that the bureaucracy can make rules and regulations to implement the law of the Legislature, it must restrain itself to the framework of the principal enactment and cannot go beyond its mandate.[7] In our case, the legislature under Section 171 of CGST has no provision for imposition of penalties in cases of anti-profiteering. On the other hand, the APR 2017 provides for penalties, even those with grave consequences such as cancelling the registration of a company. This can be argued to be an instance of excessive delegation by the Government. Moreover, the discretion given to bureaucrats to determine the violation of law and the resultant penalty has been contended by businesses to be a ‘draconian enactment’.

b. The APR 2017 may be considered as a violation of the Right to Free Trade

Article 301 of our Constitution provides freedom of trade, commerce, and intercourse throughout the territory of India. However, Article 302 authorises the Parliament to impose reasonable restrictions on this right. Nonetheless, Anti-Profiteering provisions or restriction on profits of trade of all goods or services may be treated as violation of fundamental right of freedom of Trade, hence may be subject to judicial review.

> Haphazard implementation of Section 171 and the APR 2017.

Global experience suggests that anti-profiteering provisions are only effective if there is a significant lead-in time to allow the relevant authority to educate consumers and businesses as to their respective rights and obligations. For instance, in Australia the GST transition period started precisely a year before the introduction of GST. During this period, the government undertook several measures to prepare the relevant stakeholders to comply with and make use of the various provisions of the anti-profiteering regime. On the other hand, the APR 2017 were formulated only ten days before the GST’s implementation, indicating a haphazard manner of implementation and a lack of clarity on the law.

> Lack of clarity on what constitutes anti-profiteering

The APR 2017 does not provide for a mechanism to ensure a commensurate reduction in the final price of a product. For instance, in Australia anti-profiteering measure was based on the net dollar margin rule method – that is, if taxes and costs fell by $1, then prices should also fall by at least $1. On the other hand, the APR 2017 contains neither the methodology nor the procedure for determining whether commensurate benefit has been passed on to consumers.

In fact, prices and margins are not solely dependent on taxes. Rather they are only a component of price like any other components. Price determination depends on many factors such as: Internal factors such as the cost of raw material, predetermined objectives of higher profit or higher revenue, the image of the Seller, life cycle of the product, credit period offered and promotional activities. It may also get affected by external factors such as competition of consumers, government control of economic condition, price determination of any product is most complex and continuous process, cycle of which depends on nature of product. Thus, if prices or margins are being capped on account of Anti Profiteering Measures, then it may lead to disastrous situation in many industries. Further, at times there may be strategic pricing for some products which the companies don’t want to share with anyone including tax authorities.

> Computational challenges

Practically it is very difficult to establish one to one correlation between inward tax credit on inward supplies and Tax payable on outward supplies. So ultimately it comes on margins or prices of supply. How the margins and prices are to be checked is a subjective matter. There may be various ways like, profit on product in absolute terms, profit percentage on Cost of product or profit percentage on Sale Price.

In fact, another concern raised by business is that the rules a reduction in rate of taxes of inputs or input services does not necessarily result in a proportionate reduction in the final price of a product or service and thus, this tool can be misused. Further apart from benefits in terms of better credit chain, the business organisations are going to incur huge cost for implementation of GST on account of installation of new IT systems, restructuring of operations, redesigning of SOP’s, Compliances cost etc. Whether, the organisation can set off its gains in terms of better credit flow with its increased cost, before passing of the same to consumer. Therefore, this lack clarity is another limitation of the APR, 2017.

> Subjects businesses to excessive control and harassment.

Since the APR 2017 do not have any detailed guidelines about what constitutes “anti-profiteering,” the industry fears that implementation of this law would take the market back to an era of socialism, controls and harassment at the hands of the bureaucracy. It has been argued that in their current form, the anti-profiteering rules give everything a miss and infringe upon the freedom of trade and business.

> Fuel corporate wars.

Some industry experts also point out that anti-profiteering could also be used as a tool to fight corporate wars, with businesses getting apparently unconnected individuals to complain about rivals in the market. For instance, if the purchase price of a beverage company reduces, then the competitor beverage company too would be expected to reduce the prices. In that case, there is a lack of clarity on whether the company will get penalized for not immediately reducing the price.

Thus, as is evident, the challenges to a successful anti-profiteering regime in India are many. The law has not been clearly thought through and has room for being misused. In fact, it is not even clear if the Government has the requisite in place to deal with a situation where there could well be a plethora of complaints and investigations.

Analysis of Recent Decisions on Anti Profiteering

> HONDA: – Sh. Dinesh Mohan Bhardwaj Proprietor, M/S U.P. Sales (Applicant) Vs Services Versus M/S VRANDAVANESHWREE (Respondent)[8]

Applicant booked a car (Orchid White colour, model no. WR-V 1.2 VX MT (i-VTEC)) from showroom of the respondent, being a dealer of M/s. Honda Car Ltd, vide Sale Contract dated 28.04.2017 when the ex-show room price was ₹ 9,13,300/-. Applicant requested for change in colour to Alabaster (base colour), had taken the delivery of the car on 11.07.2017 whose pre-GST show room price was ₹9,09,300/- , at ₹8,98,750/-. Applicant had alleged that combined effect of rate of tax was 51% in pre-GST regime while the total incidence of tax in GST regime is 29%, i.e, there had been a reduction of rate of tax. iv. Thus applicant filed an application dated 01.11.2017 before the Standing Committee alleging that he was not given benefit of reduced rate of Tax (GST) which amounted to profiteering.

The detailed analysis of DGSG in its report dated 23.02.2018, it is found that pre-GST rate of tax 51% was reduced to 29% in GST regime is factually in correct, instead there was a reduction of about 2%, i.e, from 31.254% to 29%. From the detailed calculation submitted by DGSG, it is found that the benefit in reduction of tax rate was passed on to the Applicant by way of reduction in the price of base colour by an amount of ₹10,550/-. as the benefit of `10,550/- on account of reduction of tax by about 2%, viz, from 31.254% (pre-GST) to 29% (in GST), has been passed on to the Applicant, no additional benefit on account of input tax credit (ITC) is required to be paid by the respondent.

Dealer’s margin tantamount to profit of the dealer and the reduction in dealer’s margin is reduction in profit margin of the dealer and cannot be equated with commensurate reduction in price due to reduction in rate of tax.[9] n the order of the Authority, the word “commensurate” hasn’t prefixed before the word “reduction”. Relevant portion of the extract is reproduced as “Thus, the benefit of reduction in the tax rate was passed on to the applicant by way of reduction in the price of the car of base colour by an amount of ₹ 10,550/-.[10]

> Schindler Lifts: M/S Abel Space Solutions LLP (Applicant) Vs M/s Schindler India Private Limited (Respondent)[11]

An application, dated 20.09.2017, was filed before the Standing Committee on 20.09.2017. Applicant had placed orders for supply of two lifts in December, 2016. First lift was delivered, against which full payment was also made during pre-GST regime. The issue is related to the second lift. The material was despatched to the Applicant on 29.03.2017. An advance was paid to the Respondent against invoice dated 28.06.2017, on which Service Tax was charged. Installation was done on 27.07.2017, i.e, in GST regime, when two more invoices were raised by the Respondent with tax (GST). It has been alleged by the Applicant that the tax (GST) has been charged without excluding the pre-GST regime Excise Duty amount on the material and hence the Respondent had charged tax twice.

The Applicant had paid advance for purchase of the second lift and the Respondent had charged Service Tax which was leviable in pre-GST regime. Supply and installation of lift amounted to “Works Contract” and as per Rule 2A of the Service Tax (Determination of Value) Rules, 2006, value of the service portion of the works contract was to be taken as equivalent to the gross amount charged for the works contract minus the value of property in goods transferred in the execution of the said contract and on the goods transferred Value Added Tax (VAT) was to be charged and on the service portion, Service Tax was leviable. Explanation to Rule 3 of Point of Taxation Rules, 2011, wherever any advance was received by the service provider against the taxable service, the point of taxation was to be construed as the date of receipt of such advance. Installation of elevator was completed in the GST regime, and hence the point for levy of tax for supply of material fell under the GST regime and accordingly, two more invoices were issued on 27.07.2017 wherein the applicable GST was correctly charged. Respondent could have passed on the benefit of Excise Duty if the material was despatched on or after 01.07.2017 and since all the materials were delivered before 30.06.2017 and hence, he was not in a position to pass such benefit to the Applicant. Based on the given facts, no substance was found in the claim filed by the Applicant and thus hereby orders dropping of the present proceedings as no violation of the provisions of section 171 of the CGST Act, 2017 has been established.

> Godrej through Flipkart: Sh. Rishi Gupta (Applicant) Vs M/s. Flipkart Internet Pvt. Ltd (Respondent)[12]

Applicant ordered a Godrej Interio Slimline Metal Almirah through the Respondent vide his order no. 110666745976477000 on 04.11.2017 and a tax invoice dated 07.11.2017 was issued to him for an amount of ₹ 14,852/- by M/s. Godrej & Boyce Mfg. Co. Ltd., Mumbai (herein after referred as Supplier). Rate of tax (GST) has been reduced by the Government of India on 14.11.2017 from 28% to 18%. iv. Another invoice dated 29.11.2017, at the time of delivery, was issued by the Supplier for an amount of ₹ 14,152/-. v. Respondent vide his letter dated 27.04.2018, intimated that excess amount of ₹ 700/- was refunded to the Applicant on 18.01.2018.

Respondent was not the Supplier / Manufacturer of the Almirah, was only an agent who had offered his platform, i.e, a market place to the Supplier to sell the Almirah by charging commission, and was also not responsible for collection or refund of tax (GST). Hence, he cannot be held accountable for contravention of section 171 of the CGST Act, 2017. Allegation of profiteering made by the Applicant against the Respondent as well as Supplier is not established and hence the present application is not maintainable and the same is dismissed. As there may be several cases, where e-platforms have collected excess tax (GST) at the time of booking which are required to be refunded. Therefore, the Authority has already directed the Director General of Audit, Central Board of Indirect Taxes and Customs vide letter No. NAA/2018/DO/08/2011 dated 24.05.2018 to audit the major e-platforms and submit its findings to the Authority. The Respondent, being an agent, offered a marketplace which enabled the sellers to offer their products for direct sale to the customers for which it was charging commission. Trade discount is part of the trade margin of the Supplier, and withdrawal of the trade discount doesn’t amount to profiteering. As base price hasn’t changed, profiteering cannot be invoked. Although the phrase “base price” hasn’t been defined in the law, it appears to be ‘taxable value’ of the product under reference. Authority can suo moto initiate action to ensure that benefits are passed on to every recipient.

> High Court’s putting stay on NAPA decisions

Different high courts in the country have given stay orders on several fiats of the National Anti-profiteering Authority (NAA) for the goods and services tax (GST), casting doubts on the legal tenability of the way the nearly one-and-half-a-year-old set-up operates and passes orders on alleged cases of profiteering by businesses. The high-profile NAA orders stayed by the courts include those related to Hindustan Unilever (`380 crore), Jubilant FoodWorks (`41 crore), Pyramid Infrastructure (`8.2 crore), Abbott Healthcare (`96 lakh) and Excel Rasayan (`5 lakh).

In many cases, the HCs have questioned the constitutionality of the anti-profiteering section of the GST Act because of lack of a set of rules or methodology to determine what constitutes ‘profiteering’ and how to calculate the amounts garnered by a business through it.

One of the principal grounds of challenge concerns the constitution of the NAPA itself. Under Rule 122 (a) of the CGST Rules the NAPA consists of a Chairman who holds or has held a post equivalent in rank to the Secretary of Government of India. Under Rule 122 (b) the 4 technical members are those who are or have been Commissioners of State Tax or Central Tax for at least one year or have held an equivalent post under the existing law. The Chairman and Members of the NAPA are to be nominated by the GST Council. In other words, there is no judicial member in the NAPA. It is further pointed out that under the CGST Rules there is no provision for constitution of an appellate authority to review the orders passed by the NAPA.[13]

Another feature of the functioning of the NAPA is that under Rule 126 it is the NAPA which determines the „methodology and procedure‟ for determining as to whether the reduction in the rate of tax on the supply of goods and services on benefit of Input Tax Credit („ITC‟) has been passed on by the registered person to recipient by way of „commensurate reduction in prices‟. In other words, it is the NAPA who determines what can amount to profiteering in a given situation. It is further pointed out that it is the NAPA which issues notice to the suspected profiteer and it is the NAPA. which adjudicates the said notice without any provisions for an appeal. It is contended that is contrary to the settled legal position regarding the constitution and functioning of quasi-judicial authorities and tribunals as explained by the Supreme Court in Union of India v. Madras Bar Association 2010 (11) SCC 1.[14]

Comparison with other jurisdictions

Most countries that have introduced a new system of taxation such as a uniform Goods and Services Tax, have adopted extra-ordinary interventionist policies not only to limit price revision but also to prevent any unjustified increase in prices by the businesses. Some of the important price intervention measures implemented across the world are (a) price freeze or control in Belgium, Netherlands and Korea, (b) price monitoring in Germany and Ireland, (c) freeze on profit margins in Netherlands and Ireland, (d) publicity campaign in Korea, New Zealand and United Kingdom, (e) enactment of counter inflation laws in United Kingdom, and (f) reduction of other taxes and subsidy payments to essential commodities in Denmark.[15] Through this section of the project, we seek to analyse the anti-profiteering laws in two such jurisdictions; Australia and Malaysia.

> Anti-Profiteering Laws in Australia

Australia introduced GST on July 1, 2000 to replace a number of existing indirect taxes including wholesale sales tax.[16] The GST implementation had a three year transition period from 1 July 1999 to 30 June 2002 during which the national competition regulator, Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [“ACCC”] was legally entrusted with the responsibility to oversee the pricing responses to the GST and to take action against businesses that adjust prices inconsistent with tax rate changes consequent to GST implementation.[17]

To ensure the smooth transition, the ACCC had many statutory duties, which included: (i) formulate guidelines about what constitutes price exploitation; (ii) seek information from businesses to effectively monitor the price movements; (iii) issue notice to the businesses in case they indulge in price exploitation; (iv) seek penalties before the Federal Court for breach of price exploitation provision by businesses and individuals; (v) accept undertakings from the businesses which are enforceable in a court; (vi) investigate complaints and issues of public concern; and (vii) provide information to both businesses and public on price exploitation provisions.

Armed with these statutory responsibilities, the ACCC undertook several measures to ensure that due to GST reforms consumers would fully benefit from the reduction in tax rates and tax cascading, that they do not experience greater than necessary increases in the prices and are not subject to price exploitation by the businesses.

To ensure this, the major initiatives taken by ACCC are the following:[18]

(a) Definition of price exploitation:

To aid its task of overseeing the pricing responses to the GST, the ACCC defined that a business is considered to be engaged in price exploitation in the process of GST implementation if (i) it regulates the supply; (ii) it increases net profit margin by not reducing its prices adequately or by increasing prices by more than the quantum of rise in taxes; (iii) it charges unreasonably high prices even after taking into account supplier costs, supply and demand conditions, and exceptional circumstances like a long-term non-reviewable price contracts entered into by businesses and price regulation prevalent in an industry.[19]

(b) Information Dissemination

A national telephone GST price hotline was established by ACCC to deal with consumer complaints and to facilitate business and consumer inquiries. Information and guidance were provided to the businesses and consumers through a website. In addition, to enable businesses to comply with its guidelines, the ACCC issued information bulletins. For instance, a detailed compliance guide titled Small Business Pricing Kit was issued to assist the small businesses in identifying and passing on to the consumers the cost savings resulting from GST. To inform the consumers and businesses about the price changes due to GST, the ACCC widely distributed a publication titled Everyday Shopping Guide with the GST. The Guide contained information on expected price movements for 185 common consumer goods and services over the six months from the date of introduction of GST. This move was aimed at making consumers vigilant about any price exploitation practices and report the same to ACCC.

(c) Commitments from Corporates

To check price exploitation, large corporates with turnovers exceeding $100 million were invited to offer a Public Compliance Commitment [“PCC”] to ACCC on voluntary basis. The PCC required the CEO of a company to submit a signed commitment/statement indicating to the public that the company is committed to complying with the ACCC’s price exploitation guidelines. In doing so, the company is required to provide appropriate information to ACCC in support of its commitment.[20] The primary objective of PCC is to provide an assurance to the consumers that businesses would not engage in price exploitation by taking undue advantage of the GST changes. However, it is to be noted that the offering of a PCC does not prevent a company from enforcement action by ACCC in case the company provides misleading information to the ACCC.

(d) Conducting Retail Price Surveys

The ACCC collected prices from retail outlets and supermarkets for a range of goods and services both before and after the introduction of GST by way of specially commissioned monthly and quarterly surveys of retail prices. The main purpose of this exercise was to collect information on price changes thereby identify areas of potential price exploitation. Price details were collected in all the eight capital cities and 100 towns across Australia.[21] Apart from retail price surveys, information gathered from other sources were used by the ACCC to study price changes and pricing behaviour.

(e) Ban on Misleading Pricing Claims

To protect the consumers against unethical business practices, under the Trade Practices Act 1974, businesses were prohibited from influencing consumer demand by making deceptive pricing claims. For instance, there were provisions in the Act to take correction action if a firm attempts to encourage consumers to make buying decisions before the implementation of GST by way of misleading advertisements such as claiming that the price would increase as a result of GST introduction though in reality it might come down. Another example of misrepresentation would include the claim by the businesses that the increase in the prices was due to an “anticipation” of the effect of tax rate changes due to GST introduction.

(f) Price and Profit Margin Rules

The ACCC devised a price rule as per which the prices charged by the businesses in response to the tax changes should not rise by more than 10 per cent in any event due to two reasons. First, the net cost of inputs/raw materials used by the businesses was not expected to increase beyond 10 per cent. Second, businesses were entitled to claim an input tax credit for the GST paid. However, businesses were allowed to adjust their prices to the extent of recouping the compliance costs associated with the GST such as purchase of new accounting software, staff training, and seeking advice specific to GST compliance. The capital expenditures like installation of a new accounting system incurred by the businesses to comply with GST were also permitted to passed on to prices over several years in line with accounting depreciation rules. As per profit margin rule, the businesses were barred from making undue profits by altering their profit margin, called net dollar margin, in the process of implementation of GST. In any case, if required, businesses were expected to justify before ACCC any change in prices due to GST introduction. While doing so, the businesses were expected to retain the official records on the basis of which pricing decisions were made by them during the GST transition period. The records may include accounting documents, invoices, minutes of directors’ meeting and diary notes. In case of shelf prices displayed at the retail shops, they were expected to be updated within 10 days of implementation of GST. If there are any practical difficulties in meeting this requirement, then the retailers were required to display notices in their stores informing the customers that the displayed shelf prices have not yet been adjusted to reflect the tax changes due to GST and hence the GST-inclusive actual prices to be paid would be calculated at the time of billing.

(g) Penalty

The ACCC was given the power to seek penalties before the Federal Court for breach of price exploitation provision by businesses and individuals. The Court could impose penalties of up to $10 million and $500000 per offence respectively for companies and individuals. Interestingly, the advisers to businesses such as lawyers and accountants were also subject to imposition of penalties on the grounds of aiding and abetting price exploitation.

The outcome of such measures was that both Australian businesses and consumers were better equipped to deal with the introduction of the GST. The ACCC’s prices oversight regime, during the transition period the ACCC (i) took into consideration over 51000 GST-related complaints and investigated around 7000 of them; (ii) obtained refunds of around $21 million for the benefit of around 2 million consumers, mostly on account of overcharged GST; (iii) accepted 55 court enforceable undertakings; and (iv) initiated court proceedings in respect of 11 GST related issues. Thirty-five companies responded to ACCC’s invitation and adopted acceptable PCC. The ACCC reported its enforcement activities on quarterly basis to the Minister as well as in its journal namely ACCC Journal throughout the transition period.[22] Also, several businesses have initiated corrective action when GST-related rule violations were brought to their attention by the ACCC.

> Anti-Profiteering in Malaysia

Malaysia introduced the GST in April 2015. Since then it has diluted the scope of its regulations. The new antiprofiteering regulations in Malaysia, which came into effect from January 2015, apply to fewer goods. Food and beverages, and household goods are still under it while the earlier law covered all.

The rules that Malaysia introduced in 2015 to deal with the danger of profiteering were detailed, wide-ranging and difficult to apply practically. These were reworked and simpler arrangements put in place. Malaysia’s anti-profiteering rules were drawn up on a formula-based approach to determine instances of “profiteering” or “unreasonably high” profit. The prescribed formula for determination of net profit margin takes into account factors such as taxes, supplier costs, supply and demand conditions, circumstances of the geographical and product market. Hence the Tax experts are of the opinion that India’s anti-profiteering provision under the GST law is more a statement of intent that does not specify any consequence of non-compliance.

A key lesson from Malaysia’s experience in price control after the introduction of the GST is that over-regulation and micro-management of market forces enhances cost of compliance and stifles growth, said experts. “In Malaysia, the aggressive enforcement of anti-profiteering provisions has been criticised strongly and have proved to be litigious and difficult to implement,”[23]

Conclusion

Thus, anti-profiteering is still a work in progress. It has been introduced to protect the interest of consumers and at the same time not harming the industry interest. The initiative surely protects the interests of the much relieved but anxious consumers from any possible chaos in near future. One of the significant benefits expected to accrue from this measure is the reduction in prices of commodities under the tax regime and its downward effect on retail inflation.

However, it cannot be denied that the APR 2017 are half baked and require a lot finer tuning, to achieve its objective. In the current format, the government’s anti-profiteering rules raise more questions than answers. While the intent is to curtail inflation post-GST implementation, the notification suffers from a lack of clarity on many aspects, increasing uncertainty for businesses. Thus, we can only hope that either the Government amends and clarifies the anti-profiteering law in India or uses these provisions sparingly and even in these select cases, only after proper due diligence.

At the same time, looking at the issues and challenges before industry and the efforts involved in reworking of cost sheet and re-fixing of prices, it is advisable that a) A reasonable bandwidth for margin variation should be prescribed, say for example variation upto 10% of existing margins. If variation remains within such bandwidth, no registered person should face any penal consequences u/s 171 of the CGST Act. b) A threshold limit for turnover of taxable supplies may be prescribed, below which provision of sec. 171 shall not apply. c) Further for above threshold limit, detailed rules, covering all aspects including computation mechanism, documents to be maintained etc, should be prescribed so that no discretionary power is left in hands of any authority which in turn can cause harassment of the tax payer.

[1] Lakshmi Kumar Sreedhan, Anti-Profiteering Measure and Price Control Mechanism under the GST (Dec. 21, 2016) accessible at https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=329e1f1b-b2c0-4474-a974-5805f54894c2.

[2] Section 171(1), Central Goods and Services Act, 2017.

[3] In accordance with Rule 4, Anti-Profiteering Rules, 2017.

[4] Rule 8, Anti-Profiteering Rules, 2017.

[5] Rule 9 and 10, Anti- Profiteering Rules, 2017.

[6] Kesavananda Bharati. v. State of Kerala (1973) 4 SCC 225.

[7] Hamdard Dawakhana v Union of India, A.I.R. 1960 S.C. 554.

[8] Sh. Dinesh Mohan Bhardwaj Proprietor, M/S U.P. Sales (Applicant) Vs Services Versus M/S Vrandavaneshwree (Respondent), 2018 (4) Tmi 1377 – The National Anti-Profiteering Authority (27-03-2018).

[9] Id., ¶ 7.

[10] Id., ¶ 15.

[11] M/S Abel Space Solutions LLP (Applicant) Vs M/s Schindler India Private Limited (Respondent), 2018 (6) Tmi 687 – The National Anti Profiteering Authority (31.05.2018).

[12] Sh. Rishi Gupta (Applicant) Vs M/s. Flipkart Internet Pvt. Ltd (Respondent), 2018 (7) Tmi 1490 – National Anti-Profiteering Authority (18.07.2018)

[13] Jubiliant Foodworks v. Union of India, W.P. (C) 2347/2019, Delhi HC (13.03.2019).

[14] Id.

[15] Tait, Alan, Value Added Tax: International Practice and Problems, Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund (1988).

[16] Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2000a), Price Exploitation and the New Tax System: General Principles, Information and Guidelines on when Prices Contravene Section 75AU of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (March, 1974).

[17] Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2001a), The GST: the ACCC’s role and the impact on prices, https://www.accc.gov.au/system/files/NSW%20Economics.pdf (March, 2000).

[18] Sthanu N. Nair, Price Monitoring and Control under GST, 52:4 Economic and Political Weekly (June, 2017).

[19] Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2000d), Price Exploitation and the New Tax System: A Compliance Guide for Small Business (May, 2000).

[20] Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2000a), Price Exploitation and the New Tax System: General Principles, Information and Guidelines on when Prices Contravene Section 75AU of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (March, 2000).

[21] Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, (2000c), Report on ACCC Price Surveys: Preliminary Post-GST Price Changes, (October, 2000).

[22] Australia Competition and Consumer Commission (2003), GST Final Report, accessible at https://www.accc.gov.au/system/files/GST%20final%20report.pdf (2003).

[23] CMA Mrityunjay Acharjee, Introduction of Anti Profiteering in India and Role of CMA, available at http://icmai.in/TaxationPortal/upload/IDT/Article_GST/16.pdf