CROSS BORDER INSOLVENCY RULES/REGULATIONS COMMITTEE (CBIRC-II)

New Delhi, December 10, 2021

To

Secretary to Government of India

Ministry of Corporate Affairs

`A’ Wing, Shastri Bhawan

New Delhi – 110001

Dear Sir,

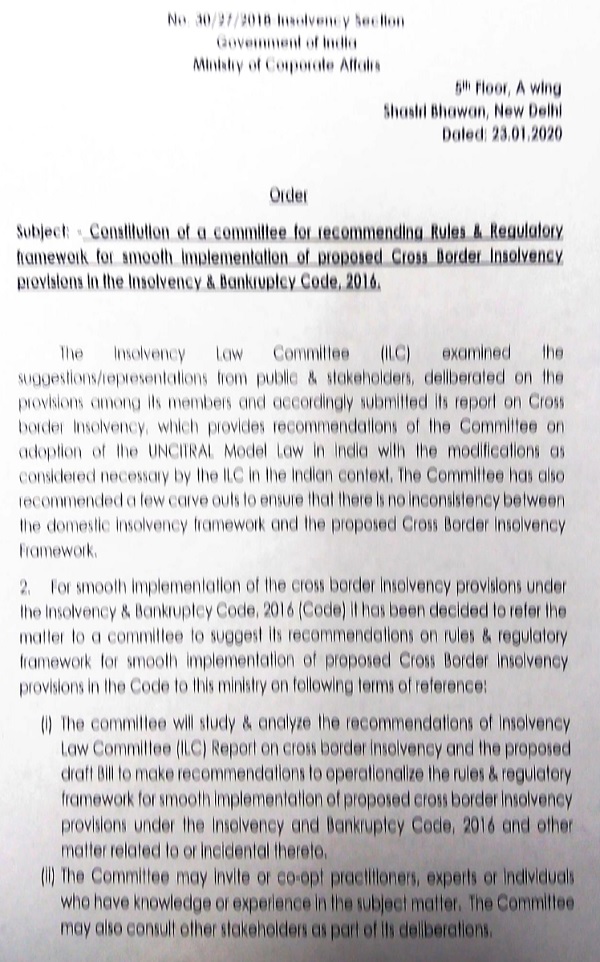

We have the privilege and honour to present the second part of the Committee’s Report to the Ministry of Corporate Affairs. The Cross-Border Insolvency Rules/Regulation Committee (CBIRC) which was constituted, vide office order No. 30/27/2018-Insolvency Section dated 23rd January, 2020, submitted first part of its report on the rules and regulatory framework for cross border insolvency on 15th June, 2020. On 21′ February, 2020, the remit of CBIRC was expanded to analyse the UNCITRAL Model Law on Enterprise Group Insolvency and to make recommendations governing the resolution of group enterprises for the purpose of the IBC.

2. The CBIRC has adopted a holistic methodology including internal meetings, engagement with stakeholders, examining past reports, global literature and best practices followed by other countries. The Committee, while making its recommendations, has attempted a draft Part that may be inserted in the Code to enable implementation of a suitable group insolvency framework.

3. We thank you for providing us this opportunity to put our thoughts together for recommending group insolvency provisions under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (Code). We believe that the enactment and implementation of group insolvency provisions would minimize costs and maximize the value of entities involved.

The Cross Border Insolvency Rules/Regulations Committee (CBIRC) is submitting the second part of its Report on enterprise group insolvency based upon UNCITRAL Model Law for enterprise group insolvency. The Committee makes certain recommendations in the context of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 to operationalise the group Insolvency part.

The Committee is thankful to all stakeholders who provided insightful comments and suggestions during the deliberations of the Committee. These insights from these interactions greatly helped the Committee in the drafting this Report.

The Committee deeply appreciates the support provided to it by the research team: Ms. Aishwarya Satija, Senior Resident Fellow and Mr. Oitihjya Sen, Research Fellow of Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, Mr. Kahnav Mahajan, Advocate, Ms. Anjali Sharma and Ms. Bhargavi Zaveri, Lead Research Consultants of Finance Research Group (FRG), Mr. M.V. Pratap Kumar, Advocate, Ms. Varsha Aithala, Research Fellow of Azim Premji University (APU), Mr. Karthik Suresh, Research Fellow of National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP), Mr. Ameya Vikram Mishra, Advocate and Mr. Yadwinder Singh, Assistant Manager of Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (IBBI). The Committee is thankful to the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy for the support provided in research and report preparation.

The Committee is grateful to Dr. M.S. Sahoo, former Chairperson, Mr. Sudhaker Shukla, Whole Time Member and Mr. Ritesh Kavdia, Executive Director of IBBI for their valuable inputs and guidance during the deliberations. The Committee is also thankful to IBBI for providing logistical, administrative and technical support for its functioning.

Chapter I: Setting the Context

1. Introduction

The business of corporations is increasingly conducted by enterprise operating as “groups”. This term covers various forms of economic organisation that are linked together by some form of ownership or control.1 The entities within a group are legally treated as separate and distinct entities except in certain circumstances envisaged in law (like common procedural filings, liability for criminal wrongs, etc.), and yet they operate as a group, tapping into one another’s efficiencies and strengths. Even decision-making for the group could reside across definitional outlines that legally define each entity within a group. Such distinct legal identity of group entities leads to various advantages2 of conducting business in the form of groups. This has prompted group structures to become a modern global reality.3

Insolvency laws, like general company laws, typically respect the principle of separate legal personality of the entities in a group and deal with each entity’s assets and liabilities separately. Consequently, insolvency statutes in most jurisdictions treat the insolvency proceedings of each group entity separately. However, such statutory frameworks may prove to be ignorant of economic realities and practicalities.

Where group entities are significantly interlinked, it may be value destructive to not recognise such interlinkages in insolvency law.4 For instance, where the business of different entities in a group are dependent on each other; or various group entities have many common assets; or where there are multiple common liabilities and related party transactions amongst various group entities, it may not be feasible to conduct insolvency proceedings for each group entity in isolation. Each entity in a group being able to tap synergies with others in the group when solvent, and yet being blind to the inter-linkages when it comes to insolvency, is anomalous. At the same time, a body corporate being a distinct legal entity with perpetual succession must not be lost sight of. Accordingly, the insolvency of entities belonging to a group may raise certain distinct problems that may not arise otherwise.5

Such problems are further exacerbated when enterprise groups operate in a transnational setting, i.e., when groups consist of entities from at least two different countries. Insolvency proceedings of group entities may affect multiple jurisdictions if the assets, liabilities or business of a group spans across different countries. In such a scenario, linking or coordinating insolvency proceedings of group entities will also require answering questions of cross-border insolvency. This includes determining the appropriate forum that will have jurisdiction to oversee the insolvency proceeding(s) of group entities; identifying the law applicable to each such proceeding, and agreeing on the manner of recognising such proceedings in other relevant jurisdictions.6

International practice in the last couple of decades has attracted the attention of various policy makers, globally, to the special challenges posed in effectively resolving insolvency of group entities. International instruments like the UNCITRAL Legislative Guide to Insolvency Law Part 3 (“UNCITRAL Legislative Guide”), the UNCITRAL Model Law on Enterprise Group Insolvency (“MLEGI”), and the EU Regulation 2015/848 on Insolvency Proceedings (recast) (“EU Regulations”) have also been developed to provide guidance on the subject. Even domestically, issues related to enterprise group insolvency have arisen in practice.

With the introduction of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (“Code/ IBC”), India consolidated the fragmented laws relating to inter alia reorganisation, insolvency resolution and liquidation of corporate persons. Although the Code comprehensively deals with the insolvency of corporate debtors as separate entities, it does not envisage a framework to either coordinate insolvency proceedings of corporate debtors belonging to a group or to have a common resolution for them. Consequently, the insolvency of different corporate debtors belonging to the same group is dealt with through separate insolvency proceedings for each corporate debtor.

However, in recent cases under the Code like “Videocon, Era infrastructure, Lanco, Educomp, Amtek, Adel, Jaypee and Aircel, special issues arose from their interconnections with other group companies.”7 Due to this, the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (“IBBI”) constituted a ‘Working Group on Group Insolvency’ (“Working Group”) under the Chairmanship of Mr. U. K. Sinha, through an office order dated 17 January 2019. The Working Group consulted various stakeholders and undertook a detailed analysis of various issues that may arise in resolving insolvency of group entities in India. Based on this, it released a report on 23 September 2019 providing comprehensive recommendations for establishing an enabling framework for group insolvency that may be implemented in phases.

Around this time, the UNCITRAL adopted the MLEGI which is a model legislation providing a comprehensive framework for domestic as well as cross-border insolvency of enterprise groups.8 Similar to other model laws released by the UNCITRAL in respect of insolvency law, the MLEGI is meant to be a flexible instrument that various countries may consider adopting, with necessary modifications. To build on the work undertaken by the Working Group, the Ministry of Corporate Affairs (“MCA”) constituted this Committee under the chairmanship of Dr. K.P. Krishnan to analyse the MLEGI through office order dated 21 Feb 2020 (as an addendum to its previous office order dated 23 January 2020), provided in Annexure I. The mandate of this Committee was to submit a report providing recommendations for group insolvency based on a review of the recommendations of the MLEGI and the Code. Prior to this, the Committee had been working on rules and regulations for cross-border insolvency under the Code and had submitted a report in this regard to the MCA on 15 June, 2020.

The Committee appreciated the recommendations of the Working Group and greatly benefited from the elaborate discussion in its report. To fulfil its mandate, the Committee consulted several stakeholders and experts, and examined relevant legal and regulatory principles as well as global best practices. Based on this, the Committee submits this report (“Report”) recommending a draft framework to facilitate insolvency resolution and liquidation of corporate debtors in a group in India, as well as recommendations of the Committee on adoption of the MLEGI.

2. Working Process of the Committee

The Committee adopted a holistic methodology including internal meetings, engagement with stakeholders, examining past reports, global literature and best practices followed by other countries, to better understand the kinds of challenges that have and may come up, in enterprise group insolvency.

The Committee met seven times. It had its first meeting on 15 June 2020 and met subsequently on 13 July, 2020, 29 September, 2020, 27 October, 2020, 11 December, 2020, 30 January, 2021 and 28 July, 2021. During these meetings, the Committee delineated policy issues arising out of the concerns raised by the members and deliberated on the same. The deliberations of the Committee were informed by inputs from its research team, which comprised of members provided in Annexure II.

The Committee consulted relevant stakeholders which included academics, practitioners, judges of foreign courts, etc. The list of stakeholders who engaged with the Committee is available at Annexure III.

3. Structure of the Report

The report is divided into two Chapters. The present Chapter provides a background to the Report. Chapter II provides the recommendations of this Committee for the design of a group insolvency framework under the Code, and regarding the adoption of the MLEGI in India. The suggested draft provisions for facilitating group insolvency, which may be inserted in the Code, are provided in Annexure IV of this Report.

4. Summary of Recommendations of the Committee

i. A group insolvency framework that is voluntary, flexible and enabling in nature should be provided under the Code. Such a framework may be introduced in phases. In the first phase, only provisions governing domestic group insolvency may be enacted. (Box 1)

ii. The MLEGI may not be adopted in India at present, and its adoption may be considered after enactment of single entity cross border insolvency laws and based on learnings from its implementation. (Box 1)

iii. Jurisprudence on substantive consolidation, i.e., pooling of assets and liabilities of an insolvent group, is already developing under the Code through case law. This is a remedy resorted to in exceptional circumstances and provisions governing substantive consolidation may not be provided in the Code at present. The need for such provisions may be contemplated at a later stage, on the basis of practice and jurisprudence evolved in this regard. (Box 2)

iv. In the group insolvency framework under the Code, a broad and inclusive definition of ‘group’ should be provided so as to include a large number of corporate debtors within the ambit of the framework. The definition of ‘group’ may be based on the criteria of control and significant ownership. This definition should be applicable to all entities that fall within the definition of a ‘corporate debtor’ under the Code, i.e., companies and limited liability partnerships. The group insolvency framework may not apply to financial service providers notified under Section 227 of the Code. (Box 3)

v. The group insolvency framework under the Code should only apply to corporate debtors in respect of whom a corporate insolvency resolution process or liquidation process is ongoing. The law shall not apply to solvent members of the group. (Box 4)

vi. A list of procedural coordination mechanisms should be available under the group insolvency framework. These are discussed below. (Para 5)

vii. Filing of joint applications for initiation of corporate insolvency resolution proceedings against multiple corporate debtors belonging to the same group may be permitted. Such applications may be filed with an Adjudicating Authority that has territorial jurisdiction over any one of the corporate debtors in respect of whom such joint application is being filed. Although filing jointly may be permitted, the application form for each corporate debtor should be separate. (Box 5)

viii. All proceedings related to corporate debtors belonging to a group may take place under the same Adjudicating Authority. To give this effect, all pending applications and proceedings under the Code in respect of a group member may be transferred to the NCLT that is the first to admit an application for triggering an insolvency resolution process in respect of any corporate debtor belonging to the group. All new applications in respect of any group member should also be filed in such NCLT. (Box 6)

ix. A common insolvency professional may be appointed as the resolution professional or liquidator of corporate debtors that belong to the same group. An insolvency professional should refuse taking such appointment if she believes that there are conflicts of interest which may affect her functions. She may approach the Adjudicating Authority for suitable directions if conflicts arise after her appointment. (Box 7)

x. A group CoC may be formed with adequate representation from CoCs of all group members (outside group coordination proceedings in points xi-xviii). This may be at discretion of the CoCs and its constitution and formation may be subject to negotiation amongst parties. The group CoC (outside of a group coordination proceeding) may only provide procedural assistance and should not be tasked with taking decisions that affect the substantive rights and obligations of the parties, which right shall continue to be available to the CoCs of the relevant group members. (Box 8)

xi. The CoCs and insolvency professionals appointed in respect of corporate debtors belonging to the same group should mandatorily be required to cooperate, coordinate and share information with each other. (Box 9)

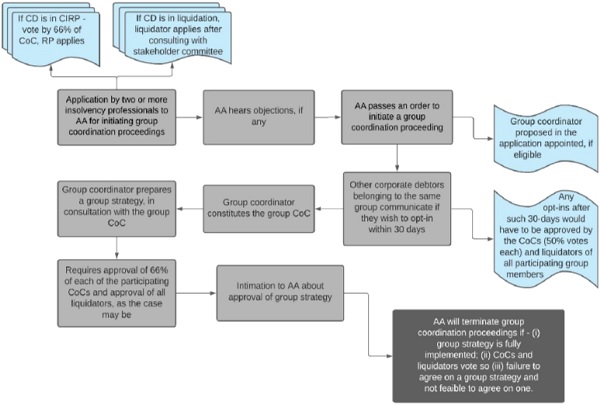

xii. The law should enable group coordination proceedings for corporate debtors belonging to the same group and undergoing a corporate insolvency resolution or liquidation process under the Code. A group coordination proceeding may be opened on application made by two or more CoCs of corporate debtors belonging to a group. If the corporate debtor is in liquidation, the application may be made by the liquidator. Such applications will be made to the Adjudicating Authority. The Adjudicating Authority may open the group coordination proceedings and appoint a group coordinator (as proposed in the application and subject to eligibility criteria). The proceedings will run alongside the separate insolvency or liquidation proceedings of the corporate debtors. (Box 10)

xiii. Participation of a corporate debtor in the group coordination proceeding should be voluntary. The CoCs may have flexibility to opt-in to the group coordination proceedings until 30 days after its opening. Any opt-ins after such time may be permitted with the approval of the participating CoCs and liquidators. For such approval, each CoC would have to vote in favour of such opt in by at least 50% of each of their voting shares. The participating group members may opt out of the group coordination proceedings at any time until a group strategy has been approved by their respective CoC. (Box 10)

xiv. The group coordinator shall constitute a group CoC consisting of suitable representatives from CoCs of all participating group members. The group CoC (in group coordination proceeding) may perform functions delegated to it by separate CoCs. However, the power to approve a resolution plan shall not be permitted to be delegated to the group CoC. (Box 10)

xv. The group coordinator will conduct the group coordination proceedings and develop a group strategy. A group strategy may provide various combinations of measures that synchronise the insolvency resolution or liquidation proceedings of the participating corporate debtors. Such measures may be different for different companies included in the strategy. The group coordinator will also assist the resolution professionals, liquidators and CoCs of the corporate debtors so as to enable effective coordination amongst them. (Box 10)

xvi. A group strategy should require the approval of all participating CoCs by 66% of each of their voting shares respectively. Where a corporate debtor participating in a group coordination proceeding is undergoing liquidation, the liquidator should decide whether to approve the group strategy for the corporate debtor it represents. Once approved, the group strategy shall be filed with the Adjudicating Authority and shall be binding on all parties to the group strategy. (Box 10)

xvii. A group coordination proceeding shall terminate if the group coordinator applies for a termination order, which may be on the grounds that – (a) the group strategy has been approved and fully implemented; (b) the CoCs and liquidators have approved such termination by requisite majority; (c) the CoCs and liquidators have failed to approve a group strategy and the group coordinator is of the opinion that it is not feasible for participating group members to agree on a group strategy. (Box 10)

xviii. The costs of conducting group coordination proceedings should form part of the insolvency resolution or liquidation process costs of the participating group members. Further, where group coordination proceedings are opened, an additional 90 days may be added to the time period for completion of the insolvency resolution process for the participating corporate debtors. (Box 10)

xix. Specific provisions to deal with perverse behaviour may not be required as provisions dealing with avoidance actions and fraudulent or wrongful trading under the Code may be sufficient. Detailed provisions targeting perverse behaviour in group insolvency scenarios should be legislated based on practice developed under the Code in due course. (Para 6)

xx. Effective capacity building measures and increase in use of technology during implementation will bolster the efficiency of the group insolvency framework. (Para 8)

Chapter II: Designing a Group Insolvency Framework for India

1. Background

1.1. Need for a comprehensive group insolvency framework

The Committee took note of the progress made in respect of group insolvency in India. It is essential to note that in the mere five years since the enactment of the Code, issues related to interconnectedness of group companies have arisen in several insolvency proceedings. This has demonstrated that there are certain special issues that may arise in the insolvency of group companies, which are distinct from the concerns that arise in single-entity insolvency proceedings.

Primarily, companies in a group may be inter-linked with each other in various ways. It is common for the operations or finances of group members to be connected to each other, and consequently, group members may undertake many related party transactions with each other.9 Disentangling the ownership of assets and liabilities and identifying the creditors of each group member may involve a complex and costly legal inquiry.10 Such disentangling may become essential if single-entity insolvency proceedings are to be carried out for more than one group member. This may be value-destructive especially where utilising synergies of the group members may result in availing better value for stakeholders. For instance, where operations and supply chains of group members are inter-linked with each other, it may be value-maximising to permit resolution applicants to bid for such group companies in a single offering.

Further, disentangling assets and liabilities of highly inter-linked group companies may actually go against the expectations and interests of creditors. Although companies are treated as separate legal entities even if they are a part of a group structure, lenders often consider the financials of the whole group when making lending decisions in respect of group members. This is especially the case when the group operates as a single economic entity in reality. Mevorach notes that strict adherence to limited liability may externalise “some of the costs of the enterprise with risks falling on outsiders”11, like creditors. Although an efficient market hypothesis posits that creditors would have adequate information about the group structure to calculate risks associated with lending to its group members, this may only be true in theory. 12 In reality, creditors often lack access to adequate information and resources to calculate such risks especially where the companies have utilised a complex group structure.13 The costs of availing adequate information for calculating such risks may also be higher than the amount of the transaction in some instances.14 Moreover, although sophisticated creditors may be well placed to make such decisions with more accuracy, dispersed and unsophisticated creditors will not have the means or incentives to undertake comprehensive and costly analyses of the degree of integration of group companies.

Therefore, adopting a purely single-entity approach in the insolvency of group members may be divergent from the economic realities of the group as viewed by stakeholders. This raises concerns about the manner of integrating or coordinating insolvency proceedings of group companies in a manner that aligns with the economic realities of the group and leads to maximisation of value. As noted above, although the Code comprehensively deals with the insolvency of corporate debtors as separate entities, it does not envisage a framework to either coordinate insolvency proceedings of corporate debtors belonging to a group or to have a common resolution for them. To address this, the Adjudicating Authorities under the Code and the Supreme Court have passed orders enabling coordination of insolvency proceedings of group members in some instances, or have applied general principles of corporate law pertaining to piercing of the corporate veil to make group companies liable for each other.15

The Committee took note of the above and agreed that the Code should provide guidance on the manner of undertaking insolvency proceedings of group companies that is distinct from the current single-entity approach. It discussed that since the Committee is tasked with forming recommendations regarding adoption of the MLEGI, it may be beneficial to first formulate key features of a group insolvency framework that aligns with the principles of the Code. The approach of the MLEGI may be considered alongside this to finally arrive at a suitable framework to undertake insolvency of group companies under the Code.

1.2. Overview of the recommendations of the Working Group

As noted above, the Working Group under the chairmanship of Mr. U. K. Sinha recommended principles for designing a comprehensive and effective framework for group insolvency in India. To arrive at this, the Working Group analysed the law and jurisprudence on group insolvency in jurisdictions like Germany, the UK and the US as well as international instruments like the EU Regulations and the UNCITRAL Legislative Guide. However, since the MLEGI was released shortly before the release of the report of the Working Group, the framework suggested in its report does not consider the recommendations of the MLEGI on group insolvency.

The Committee appreciated the recommendations of the Working Group and greatly benefited from the elaborate discussions provided in its report. An overview of the key components of the framework suggested by the Working group is provided below:

- The Working Group recommended that the framework for group insolvency should be voluntary and enabling in nature. It proposed a flexible mechanism that creditors or liquidators of group companies may opt for and is not mandatorily imposed for all group companies undergoing CIRP or liquidation under the Code.16

- The framework is envisaged to be implemented in phases. In the first phase, the framework would facilitate the introduction of procedural co-ordination of only domestic companies in groups and rules against perverse behaviour. Cross-border group insolvency and substantive consolidation would be considered at a later stage, depending on the experience of implementing the earlier phases of the framework.

- Various modes of procedural coordination would be available to group members. However, this would be limited to corporate debtors belonging to the group that are undergoing CIRP or liquidation proceedings and not to solvent members of the group. The procedural coordination mechanisms that would be available to such corporate debtors would include filing of joint applications; communication, cooperation and information sharing; appointment of a single or common insolvency professional; having a common Adjudicating Authority; and undertaking group coordination proceedings. Such procedural coordination may be enabled at any stage of the CIRP or liquidation process of the group members.

- The framework would have certain rules against perverse behaviour. The provisions enabling the avoidance of certain transactions and imposition of liability for wrongful and fraudulent trading may broadly be sufficient to capture intra-group transactions that are value destructive. An additional mechanism to subordinate intra-group claims in exceptional circumstances would also be available.

1.3. Overview of the MLEGI

International group insolvency poses a complex problem. Devising and agreeing upon an effective legal international instrument to address this problem is unsurprisingly a challenge. Enterprise groups comprise separate entities that are connected through ownership, control, or coordination. Although legally split into separate entities, groups are often economically, administratively, or financially integrated and therefore require some form of global group approach.17 A coordinated response to international insolvency of enterprise groups is critical for ensuring value maximisation for the benefit of the enterprise stakeholders. Generally, harmonization and uniformity across jurisdictions is necessary to avoid the “chaos” generated by conflicting private international law rules and to allow for a fair and efficient global collective process. Due to the economic integration of the group, the insolvency of one entity affects the rest of the group, or the entire integrated enterprise faces financial or operational distress simultaneously.18

Various countries deal with this issue differently, leading to the lack of a uniform global approach. The MLEGI was developed against this backdrop and was adopted by the UNCITRAL in 2019. It is a flexible instrument that may be adopted by countries with modifications, as may be required, to make it suitable to the jurisdiction’s domestic context. It builds on the recommendations contained in the UNCITRAL Legislative Guide, which was released in 2010. Whereas the UNCITRAL Legislative Guide concentrates on domestic group insolvency, the focus of the MLEGI is resolving the insolvency of multinational enterprise groups. Therefore, the provisions of the MLEGI chiefly deal with cross-border issues that may arise in the insolvency of such enterprise groups. A discussion of the key components of the MLEGI from a cross-border perspective are provided in para 7 of this Chapter.

1.4. Committee’s Approach

The Committee therefore had the benefit of the framework laid down in the MLEGI in addition to the Working Group’s recommendations. The Committee undertook detailed consultations with international experts on the subject of group insolvency, including judges, practitioners and academicians, to better understand the nuances and technicalities involved in dealing with corporate insolvency on a group level rather than an entity level.

Based on the above, the Committee concluded that there are several benefits of introducing a framework to deal with insolvency proceedings of corporate debtors that belong to the same group. The key benefits in this regard are provided below:

i. Firstly, acknowledging economic realities of the group in the insolvency law will lead to maximisation of value available to stakeholders. By tailoring the insolvency processes to suit the circumstances of the case, stakeholders would be able to utilise synergies of the group to achieve better outcomes from the insolvency process.

ii. Secondly, an effective group insolvency framework would facilitate the reduction in costs of the insolvency process. Coordinating or consolidating insolvency proceedings of group companies would reduce costs associated with duplication of efforts. Further, costs associated with disentangling significantly inter-linked groups may also be eliminated.

iii. Thirdly, judicial time spent on the proceedings may significantly reduce if the insolvency proceedings of group companies are dealt with in a coordinated or consolidated manner. Considering that the issues related to group insolvency often involve commercial considerations, group insolvency frameworks place substantive reliance on creditors and insolvency professionals to find optimal solutions that suit the group. On the other hand, courts are often left to find solutions to address such issues themselves in the absence of a legislative framework on group insolvency. For instance, in the insolvency proceedings of various Videocon companies, the Adjudicating Authorities under the Code had to devise strategies to develop the optimal manner of resolving the companies together.19 Thus, courts would also save the time that they may have spent on finding ways to address issues related to group insolvency on an ad hoc basis.

iv. Finally, providing legislative guidance on group insolvency may make the insolvency law more effective in serving the needs of creditors. This may happen in two ways. One, since the framework promotes information symmetry between parties, creditors will have access to adequate information to facilitate better decision-making. Two, creditors may also be able to make more informed decisions ex ante since they will have certainty regarding the manner in which insolvency proceedings in group scenarios will take place.

Accordingly, the Committee noted that there are various benefits to designing a legislative framework for group insolvency that may be inserted in the Code. It discussed that such a framework should be enabling, flexible and voluntary in nature so as to suit different ways in which groups may be inter-linked. Thus, the Committee has prepared-

(i) a list of recommendations for designing a group insolvency framework, as detailed in this Chapter; and

(ii) a draft group insolvency framework, designed based on these recommendations, which may be inserted in the Code (Annexure IV). This may be referred to as ‘Draft Part ZA’ in this report. Notably, consequential amendments to existing provisions of the Code may also be required if this Part is inserted in the Code.

2. Jurisdictional Scope and Considerations for Adoption of the MLEGI

The treatment of corporate entities as groups instead of separate legal entities is a nascent issue in insolvency scholarship and practice. Although the practice of a few countries already accounted for coordination or consolidation of insolvency proceedings of group entities20, global attention for this issue was garnered after the collapse of corporate giants in recent times. Despite this, the enactment of statutory provisions within insolvency laws to deal with groups has only taken place in few jurisdictions. Therefore, precedent of statutory provisions in this area is limited and practice in this regard is still evolving across the world.

In order to promote harmonisation of laws on enterprise group insolvency on a global scale, the UNCITRAL recently adopted the MLEGI. This Committee considered whether the MLEGI should be adopted in India at this stage. Towards this end, the Committee studied the MLEGI and observed the following:

- The MLEGI is a flexible instrument that may be adopted by countries with requisite modifications to make it suitable to the jurisdiction’s domestic context. It builds on the recommendations contained in the UNCITRAL Legislative Guide, which was released in 2010. Whereas the UNCITRAL Legislative Guide concentrates on domestic group insolvency, the focus of the MLEGI is resolving the insolvency of multinational enterprise groups. Therefore, the provisions of the MLEGI chiefly deal with cross-border issues that may arise in the insolvency of such enterprise groups.

- The complexity of the issues involved in the insolvency of group enterprises is exacerbated when different entities belonging to the group are situated in different countries. In fact, cross-border insolvency raises questions that are often difficult to resolve even in single entity insolvency. Firstly, the substantive laws on insolvency in different countries are unharmonized.21 If the insolvency proceedings of group enterprises being conducted in different jurisdictions are to be coordinated or consolidated, it will often lead to a conflict concerning the appropriate applicable law. Further, the difference in the treatment of various stakeholders in different jurisdictions may also disincentivize cooperation among the countries involved with each other.22 Secondly, determining the appropriate jurisdictions where the debtor may be subject to insolvency proceedings is a critical issue in cross border insolvency cases. In a group insolvency scenario, the determination of the place where proceedings of group enterprises should be consolidated is often the most contentious issue and may be prone to long, costly litigation.23 Thirdly, procedures for recognition and enforcement of foreign court orders need to be established in the jurisdictions where insolvency proceedings of the group enterprises can take place.

- Determination of the above issues in a jurisdiction, in a predictable and consistent manner, can be challenging. The basis on which the above three issues are resolved is the choice that a jurisdiction makes between the approaches of territorialism, universalism and its hybrids forms.24 This requires an assessment of the policy approach towards insolvency proceedings in foreign jurisdictions. Given that currently India has not notified about half the provisions of the Code, the absence of a cross-border insolvency framework for single-entity insolvency and, the fact that the MLEGI itself is relatively nascent, the Committee felt that determining this policy approach for group insolvency of multinational firms may be premature.

- In a cross-border insolvency scenario, there are numerous ways in which groups can be structured across countries. Therefore, a law governing cross-border group insolvency will need to provide flexibility, and will inevitably involve discretion for courts and office holders, to account for various kinds of cases that may come up. Accordingly, effectively resolving the issues involved in cross-border group insolvency requires significant expertise and sophistication by officeholders, courts as well as other stakeholders in the insolvency ecosystem. Moreover, cross-border cooperation in insolvency involves communication between courts and office holders that are situated in different countries and thus, requires substantial infrastructural and administrative capacity.

- In addition to the above, the MLEGI was adopted by the UNCITRAL two years ago and has not been adopted by any country until now. Therefore, the degree of international consensus on the MLEGI and the expected modifications to it, on adoption in other jurisdictions, is yet unclear. It is important to note that model legislations that are based on universality principles may only be effective in harmonising laws if they are adopted by multiple countries.

Based on the above, the Committee agreed that the MLEGI may not be adopted in India at present. Instead, the Committee recommends that a framework only for domestic group insolvency should be provided in the Code. The provisions for group insolvency may be enacted and implemented in phases. In the first phase, the framework for group insolvency may only apply to domestic entities of corporate groups. Provisions on cross-border group insolvency may be enacted in the second phase, after practice and jurisprudence on single entity cross-border insolvency and domestic group insolvency has been established.

In order to nevertheless benefit from the insights provided in the MLEGI, the Committee has reviewed the framework suggested by the Working Group in light of the principles available for domestic group insolvency in the MLEGI and the UNCITRAL Legislative Guide. The recommendations of the Committee are discussed below.

Drafting Instructions (Box 1)

- The MLEGI may not be adopted by India at present.

- Adoption of the MLEGI may be considered after enactment of single entity cross border insolvency laws and based on learnings from its implementation.

- A group insolvency framework should be laid down under the Code that is voluntary, flexible and enabling in nature.

- The group insolvency framework may be introduced in phases. In the first phase, only provisions governing domestic group insolvency may be enacted.

3. Scope of Coordination under Draft Part ZA

There are broadly two kinds of coordination strategies that may be adopted in the insolvency of group companies. One, substantive consolidation is a mechanism whereby the assets and liabilities of different group companies are consolidated so that they are treated as part of a single insolvency estate for the purpose of reorganization or distribution in liquidation. On the other hand, procedural coordination may be undertaken to coordinate concurrent insolvency proceedings of group companies whereby the procedures of such proceedings are synchronised. Instead of pooling assets and liabilities of group entities, procedural coordination involves the synchronisation of various aspects of the manner in which the insolvency proceedings of group companies are administered.25

The Committee deliberated on the kinds of coordination that may be permitted under the group insolvency framework under the Code. Its deliberations regarding procedural coordination are provided in para 5. In order to understand the nuances of substantive consolidation, the Committee first undertook a review of international practice in this regard.

Globally, substantive consolidation of assets and liabilities of group members in insolvency is rare and is only utilised in limited circumstances. Since limited liability and entity separateness are one of the most fundamental principles of corporate law, disregarding them through substantive consolidation is perceived as a radical remedy. Nevertheless, the law or practice in many jurisdictions recognise that undertaking substantive consolidation may be beneficial in some scenarios. The UNCITRAL Legislative Guide on Insolvency Law lists down the following factors while determining the liability of related companies in a corporate group: –

(i) the degree to which the administration, management and finances of the companies are interlinked;

(ii) the conduct of the related company towards creditor of the insolvent company; and

(iii) whether creditors considered the two or more business entities as one economic unit and whether the actions of the related company have led to insolvency.

However, the UNCITRAL Legislative Guide Part III recommends limiting the use of substantive consolidation to two scenarios. First, if the court is satisfied that the assets or liabilities of the group members are intermingled in such a manner that it is difficult to identify the ownership of assets and liabilities without disproportionate expenses or delay. Second, if the court is satisfied that the entities of the same group are engaged in fraudulent activity, and if substantive consolidation is essential to rectify such activity. The MLEGI is silent on the issue of substantive consolidation.

The insolvency law in some jurisdictions allows courts to order substantive consolidation if certain pre-requisites are met. Jurisdictions such as Australia and New Zealand have enacted provisions to guide courts on the circumstances in which consolidation may be ordered. Section 271(1)(b) of the Companies Act, 1992 of New Zealand allows the court to order that liquidation of companies of a group may be undertaken as if they are one entity if the court thinks it is ‘just and equitable’ to do so. The court will rely on the following factors to conclude whether passing such order is just and equitable: –

“(a) the extent to which any of the companies took part in the management of any of the other companies:

(b) the conduct of any of the companies towards the creditors of any of the other companies:

(c) the extent to which the circumstances that gave rise to the liquidation of any of the companies are attributable to the actions of any of the other companies:

(d) the extent to which the businesses of the companies have been combined:

(e) such other matters as the court thinks fit.”26

Similarly, under Australian law, assets and liabilities of group companies may be pooled during liquidation proceedings. Such pooling takes places if the liquidator determines that it should take place and if unsecured creditors of each company approve this determination made by the liquidator.27 Creditor consent for consolidation of assets and liabilities of a parent and its subsidiary is also required in Japan.28

In the US, substantive consolidation has borne out of practice. The Committee was informed, during its consultations with international experts, that consolidation orders in the US are only provided in rare circumstances but are becoming more common in recent years. Experts suggested that different courts in the US adopt different factors for determining if pooling is necessary and beneficial. Some common factors relied on by most courts are the extent to which group entities are inter-linked; whether creditors treated the group as a single entity; common directors and officers; intercorporate financing and guarantees; degree of difficulty in separating mingled assets and liabilities; failure to observe corporate formalities; etc. The effect of consolidation on creditors is also a factor that courts consider in the US. In Auto-Train Corpn. Inc. v. Midland-Ross Corpn.29, the court laid down that to balance the interests of stakeholders “a court must conduct a searching inquiry to ensure that consolidation yields benefits offsetting the harm it inflicts on objecting parties.” Further, courts in the US may order consolidation to different degrees based on the facts of the case and may not order complete consolidation in all instances.

In respect of the UK, experts consulted by the Committee discussed that courts are more reluctant to order consolidation due to the focus on entity separateness. However, courts order asset pooling and adjustment of inter-company liabilities for companies belonging to the same group and substantive consolidation may also be effected under a scheme of arrangement.

The Committee took note of the above practices and discussed that different jurisdiction adopt different standards for the scenarios where consolidation may be appropriate and the suitable authority to make this decision. It is important to note that although the Code does not provide rules on substantive consolidation, Adjudicating Authorities have ordered consolidation in a number of instances. In State Bank of India & Anr. v. Videocon Industries Ltd. & Ors.,30 the insolvency proceedings of 13 out of 15 companies belonging to the same group were ordered to be consolidated based on the following set of factors: –

(i) common control;

(ii) common directors;

(iii) common assets;

(iv) common liabilities;

(v) inter-dependence of the companies;

(vi) interlacing of finance;

(vii) pooling of resources;

(viii) co-existence for survival

(ix) intricate links between companies;

(x) intertwined accounts;

(xi) inter-looping of debts;

(xii) singleness of economic of units;

(xiii) common financial creditors.

Due to the lacuna in the Code, the Adjudicating Authority relied on jurisprudence in jurisdictions like the US and UK. A resolution plan has been approved for these companies by the National Company Law Tribunal (Mumbai) (“NCLT”) vide a recent order dated 8 June 2021 (this has been stayed on appeal).31 In another recent case, the NCLT Mumbai consolidated insolvency proceedings of various group companies of Lavasa Group on the basis that the insolvency of the subsidiaries depended on the outcome of the insolvency of the parent company.32 Similarly, in the case of Edelweiss Asset Reconstruction Company Limited v Sachet Infrastructure Pvt Ltd.33, insolvencies of five group companies involved in developing a common township were consolidated by the National Company Law Appellate Tribunal (“NCLAT”), in the interests of homebuyers.

The Committee discussed that Adjudicating Authorities have been prompt in responding to economic realities of companies in insolvency proceedings even where the law does not so envisage, to enable value maximising outcomes for stakeholders. It is evident from the jurisprudence developing under the Code that Adjudicating Authorities have not just considered the economics of the companies undergoing insolvency but have also attempted to balance the interests of stakeholders and ensure that they are not prejudiced by consolidation. The Committee noted that designing rules for substantive consolidation may not be required when the jurisprudence in this regard is already evolving. A set of factors for determining the need for consolidation has been set out in case law and has been applied in subsequent cases. Even in other jurisdictions like the US and UK, the notion of substantive consolidation is created out of practice and not statute. This may be because the nature of substantive consolidation is such that the mix of factors and degree of consolidation applicable to a case will be significantly dependent on the facts and circumstances of the case and will vary from case-to-case. Thus, it may be suitable for the law on substantive consolidation to be guided by experience and learning from practice established under the Code in India. Moreover, the complexities involved in applying substantive consolidation require a deeper and thorough analysis to be translated into statutory norms.

Based on the above, the Committee agreed that it may be suitable to design legislative rules on substantive consolidation at a later stage. Such rules may be designed based on the learnings derived from practice and jurisprudence developed by Adjudicating Authorities under the Code. It was noted that NCLTs should continue to be prompt in considering if substantive consolidation is required following the practice set by the aforementioned decisions. However, NCLTs should be mindful that substantial consolidation is only a remedy for exceptional circumstances and should not be provided where effective outcomes can be achieved through procedural coordination.

Drafting Instructions (Box 2)

- Substantive consolidation involves the pooling of assets and liabilities of an insolvent group and is a rare remedy utilised in insolvency of group enterprises.

- Jurisprudence on substantive consolidation is already developing under the Code through case law.

- Provisions governing substantive consolidation may not be provided in the Code at present. The need for such provisions may be contemplated at a later stage, on the basis of practice and jurisprudence evolved in this regard.

4. Applicability of Draft Part ZA

4.1. Definition of ‘Group’

The manner of defining the term ‘group’ will play a key role in determining the applicability of the group insolvency framework. Table 1 gives an overview of the definition of a group prescribed by the UNCITRAL Legislative Guide, MLEGI and the Working Group.

Table 1: Overview of the Definition of ‘Group’

| MLEGI | UNCITRAL Legislative Guide |

Working Group |

| Applies to ‘enterprise groups’, which includes a broad set of organisations and not just corporations. | Applies to ‘enterprise groups’, which includes a broad set of organisations and not just corporations. | Applies to ‘corporate groups’, which only includes corporate debtors under the Code. |

| Enterprise group means two or more enterprises that are interconnected by control or significant ownership.Control is the capacity to determine, directly or indirectly, the operating and financial policies of an enterprise. |

Enterprise group means two or more enterprises that are interconnected by control or significant ownership.

Control is the capacity to determine, directly or indirectly, the operating |

Corporate group includes holding, subsidiary and associate companies as defined in the Companies Act, 2013. The Adjudicating Authority may include other companies under this definition if they “are so intrinsically linked as to form part of a ‘group’ in commercial understanding …

as long as it can be demonstrated that this will result in maximisation of value of the insolvent company without destroying the value of the company being included, so that there is overall value maximization.”34 |

Committee’s Deliberations

During the course of consultations with international experts, the Committee noted a view that the law should allow for a wider group of companies to be part of a group insolvency, as opposed to a narrower sub-set of a group. The procedural coordination framework envisaged in a group insolvency is largely facilitative, aimed at reducing administrative costs and aiding in the development of a unified resolution plan involving multiple group members on a consensual basis. Importantly, procedural coordination mechanisms respect the separate legal personalities of each participating member of a group and do not affect their respective assets and liabilities. Given this, it was suggested before the Committee that there may not be any harm in adopting an inclusive and wide definition of the term ‘corporate group’ as has been recommended by the UNCITRAL Legislative Guide. Instead, such a definition would allow a wide range of corporate groups to avail the benefits of procedural coordination.

In light of the above, the Committee noted that the definition proposed by the Working Group would be applicable only to domestic groups as the provisions of the Companies Act, 2013 apply only to companies and bodies corporate incorporated in India.35 On the other hand, the definitions recommended by the UNCITRAL Legislative Guide and the MLEGI, by virtue of being wider in nature, would equally apply to domestic and cross-border groups. Given this, the Committee discussed whether the Code should prescribe a single definition of ‘group’ for both the domestic and cross-border frameworks for group insolvency.

Pertinently, as noted above, the Committee recommends that the implementation of the group insolvency framework to multinational groups should be undertaken at a later stage. Thus, it is possible to presently recommend a definition of ‘group’, taking into consideration factors relevant only for the domestic group insolvency framework. However, if this approach is adopted, the definition of ‘group’ would require to be amended at the time of implementation of the cross-border framework for group insolvency. Alternatively, it may result in the development of two definitions of ‘group’- one for the domestic framework and another for the cross-border framework. The former would not be ideal, as it may reduce clarity or cause confusion regarding the applicability of the domestic framework to existing commercial transactions. On the other hand, the latter may result in the same group of debtors being treated as a ‘group’ under one framework while being excluded from the respective definition under the other framework. The Committee concluded that having a consistent definition for both – the domestic and cross-border group insolvency frameworks – would ensure certainty. Given this, cross-border considerations should be kept in mind while defining a ‘corporate debtor’ even if the same is applicable only to domestic groups in the first phase of implementation.

Formal vs. functional approach

The Committee noted that the definition of the term ‘group’ may either be based on –

- a formal approach, such as the existence of shareholding or voting rights of a specified threshold; or

- a ‘functional approach’ by focusing on the existence of ‘control’, which may be direct or indirect, actual or potential.36

Both these approaches offer certain benefits. If the former is adopted, it would ensure ex-ante certainty, as it would be based on objective thresholds. The Committee noted that this approach was advocated by the Working Group.37 Some members of the Committee were of the opinion that a similar approach should be adopted by this Committee as well, as the concepts of ‘holding company’, ‘subsidiary’ and ‘associate company’ are well established in practice and will ensure that creditors will have prior knowledge, at the time of sanctioning a loan, regarding whether they are interacting with a member of a group.

On the other hand, the latter approach, namely a functional approach, provides a broader and inclusive definition, which has the potential of ensuring that a wide variety of enterprise groups fall within its scope. In this regard, the Committee noted that, globally, the organizational structures of groups vary to a great extent. Groups may be structured on the basis of equity, wherein a group of entities are linked to each other by virtue of a common shareholder or set of shareholders (like a family). The simplest form of equity-based groups would involve a pyramidal structure, comprising one parent company and multiple wholly-owned subsidiaries. There may be other more complicated structures as well, comprising of multiple subsidiaries and sub-subsidiaries, involving “interlocking webs of majority and minority holdings”.38 Apart from equity, control within a group may be established by contractual arrangements and interlocking directorships, as well.39 Entities may also be linked to each other by way of joint ventures, strategic alliances, and other forms of contractual arrangements, including “franchisees, distributors, licensees, and other independent contractors.”40

Considering the wide variety of forms in which groups may exist in practice, the Committee is of the view that a prescriptive definition that is only based on objective thresholds, while ensuring certainty, may fail to include all kinds of enterprise groups.41 Such a definition may prevent courts from recognising the economic realities of such groups, and thus prove to be inadequate.42The Committee also noted that, insofar as procedural coordination is concerned, there is no potential harm in allowing a wide range of entities to be included within the definition of a ‘group’, as the same is a voluntary and enabling mechanism, aimed at reducing administrative costs and increasing efficiency, without affecting the assets and liabilities of each participating member.43 Given this, the Committee recommends that the Code should provide an inclusive definition of ‘group’ which may be based on the existence of control or significant ownership, similar to the ones recommended in the UNCITRAL Legislative Guide and the MLEGI. The Committee also discussed that the terms ‘control’ and ‘significant ownership’ should be defined in the Code to ensure that there is sufficient clarity in the applicability of the group insolvency framework.

In respect of the term ‘control’, it was noted that this term has been defined in various legislations while defining the meaning of a ‘group’. For instance, different definitions of ‘control’ are provided in the Companies Act, 2013, the Competition Act, 2002, the SEBI Takeover Regulations, etc. A definition for control has also been provided in the MLEGI. On studying these definitions, it was felt that there is benefit in utilising the jurisprudence under the Companies Act in this regard as it already applies to all companies in India. The Committee agreed that the definition of ‘control’ under the Companies Act, 2013 may be inserted in the Code. Suitable modifications may be made to this definition to account for control in limited liability partnerships.

In respect of ‘significant ownership’, the Committee noted that this term has not been defined in other Indian laws for the purposes of defining the meaning of a ‘group’. However, the ability to exercise 26% or more of voting power by one company in another is usually considered as a sufficient threshold for considering them to be part of a group. For instance, a 26% ownership criterion is used in the definitions of ‘group’ in Section 5 of the Competition Act, 2002, in Article 2.1.25 of FDI Policy 2020, etc. Given this, the Committee agreed that ‘significant ownership’ may be defined as the ability to exercise 26% or more voting power. The Committee also discussed that the definitions of control and significant ownership should be inclusive so as to provide flexibility to Adjudicating Authorities to apply the definition broadly.

The applicability of a principle-based definition, as recommended above, would be subject to factual determination by courts, on a case-to-case basis. While this will ensure that Adjudicating Authorities can recognize a wide variety of groups, it may also, at the initial stage, result in lack of clarity regarding its scope, owing to conflicting judicial interpretations. To prevent this, and to provide sufficient guidance to Adjudicating Authorities, the Committee recommends that an Explanation may be provided to this definition, to clarify that holding companies, subsidiaries and associate companies, as defined under the Companies Act, 2013, would fall under the definition of a ‘group’.

Inclusion of all ‘corporate debtors’

The Committee noted that groups typically involve a wide variety of entities, in addition to companies.44 However, the Working Group had recommended that the term ‘corporate group’ should only apply to companies and “not all corporate debtors”, as it was of the view that “more evidence may be required to build a case that group structures routinely include other forms of entities such as partnerships and trusts.”45 In this regard, the Committee noted that the term ‘corporate debtor’ has been defined as-

“a corporate person who owes a debt to any person”46 and the term ‘corporate person’ has been defined as “a company as defined in clause (20) of section 2 of the Companies Act, 2013 (18 of 2013), a limited liability partnership, as defined in clause (n) of sub-section (1) of section 2 of the Limited Liability Partnership Act, 2008 (6 of 2009), or any other person incorporated with limited liability under any law for the time being in force but shall not include any financial service provider”.47 (Emphasis Supplied)

As Part II of the Code applies “to matters relating to the insolvency and liquidation of corporate debtors”48, the provisions relating to the corporate insolvency resolution process (“CIRP”) and liquidation process apply equally to all kinds of entities covered under the definition of ‘corporate debtor’. As the group insolvency framework is intended to apply to insolvency proceedings provided under Part II of the Code, the Committee was of the view that the term ‘group’ should not be restricted solely to companies but apply to all kinds of corporate debtors, as defined under Section 3(8) of the Code.

However, the Committee did not envisage inclusion of financial service providers within this framework and considered it suitable to limit the applicability of the present framework to corporate debtors under Part II of the Code, excluding financial service providers notified under Section 227.

Drafting Instructions (Box 3)

- A broad and inclusive definition of ‘group’ should be provided in the Code so as to include a large number of corporate debtors within the ambit of the group insolvency framework.

- The definition of ‘group’ may be based on the criteria of control and significant ownership.

- This definition should be applicable to all entities that fall within the definition of a ‘corporate debtor’ under the Code, i.e., companies and LLPs. The group insolvency framework may not apply to financial service providers notified under Section 227 of the Code.

4.2. Solvent entities

The applicability of the Code is limited to debtors who have committed a default and insolvency proceedings cannot be commenced against debtors who have not committed a default. This is evident from the text of Section 4 which provides that provisions of Part II of the Code only apply to corporate debtors who have committed default of the amount prescribed therein.

The MLEGI does not specifically discuss the issue of inclusion of a solvent group member within frameworks for procedural coordination. Although it allows solvent group members to voluntarily participate in the insolvency proceedings of a group member, such participation is limited to any aid such member wants to voluntarily offer.49 Further, Article 1 of the MLEGI lays down its scope and provides that it “applies to enterprise groups where insolvency proceedings have commenced for one or more of its members, and addresses the conduct and administration of those insolvency proceedings and cross-border cooperation between those insolvency proceedings.”50 This indicates that the MLEGI comes into operation only when insolvency proceedings are initiated against one or more group members, and its scope is limited to addressing such insolvency proceedings.

The Committee took note of the above. During consultations with international experts on this subject, it was suggested that group insolvency frameworks are typically limited to entities of a group that are already insolvent and sometimes entities that may become insolvent soon. In the UK, for example, courts are generally reluctant to include a solvent entity in administration proceedings unless the entity is likely to be insolvent or such inclusion would lead to better returns for the creditors. In respect of the MLEGI, experts consulted by the Committee noted that the MLEGI permits voluntary participation of solvent entities in the insolvency proceedings of a group enterprise if it leads to benefits for the enterprise and leads to better outcomes. However, in line with the UNCITRAL Legislative Guide, it assumes that insolvency proceedings can only be opened for entities that meet the commencement standard and not for solvent entities of the group.

On the basis of the above, the Committee discussed if the group insolvency framework should apply to solvent entities. It noted that the scope of the Code is limited to scenarios of insolvency and liquidation and does not extend to pre-insolvency scenarios. Therefore, applying a group insolvency framework under the Code to pre-insolvency scenarios may not be suitable. Further, the Code adopts a simple default test for triggering insolvency, which is meant to simplify and enable timely initiation of insolvency proceedings. Since the Code is built with early detection of insolvency as an objective, creditors can easily initiate insolvency. Thus, judicial determination of whether a connected entity will become insolvent in the near future may be time-consuming and unnecessary. Given this, the Committee agreed that the framework for group insolvency shall not apply to solvent entities in a group.

Drafting Instructions (Box 4)

- The group insolvency framework under the Code should only apply to corporate debtors in respect of whom a corporate insolvency resolution process or liquidation process is ongoing. The law shall not apply to solvent members of the group.

5. Procedural Coordination

Procedural coordination is a way of coordinating concurrent insolvency proceedings of entities belonging to a group, by which the procedures of such proceedings are synchronised. This does not entail pooling of the assets of group entities, and therefore, does not alter substantive rights or liabilities of parties. Instead, such coordination is limited to synchronising various aspects of the manner in which the insolvency proceedings of group entities are administered.51 Thus, the individual group entities retain their separate identities, their separate insolvency estates, and their separate bodies of creditors even when their insolvency proceedings are being procedurally coordinated.52

Due to the varying nature of group structures and the need for coordination in their insolvencies, there is no single blueprint for the manner in which procedural coordination would be applied in every case. The popular approach that is followed by most jurisdictions, in this regard, is to create an enabling framework that permits numerous ways of coordinating insolvency proceedings of group entities. For instance, the insolvency law may permit that applications for initiation of insolvency against group members be filed jointly; the insolvency proceedings be conducted in a common forum; a common insolvency practitioner be appointed in such proceedings; notices of the proceedings be issued jointly; etc. Parties are then free to choose the appropriate coordination mechanism that suits the practical realities of their group structure, subject to supervision of courts.

The key benefits that procedural coordination mechanisms provide are reducing administrative costs of conducting the insolvency proceedings, preventing duplication of efforts of stakeholders, and enabling information sharing between creditors, insolvency professionals and courts.53 This may further aid in availing better value cumulatively from the insolvency proceedings of the group entities.54 In some cases, parties and courts may also come to the conclusion that procedural coordination is not necessary. For example, when there are no significant interlinkages between group entities that are undergoing insolvency proceedings, coordinating such proceedings may lead to no substantial benefit.

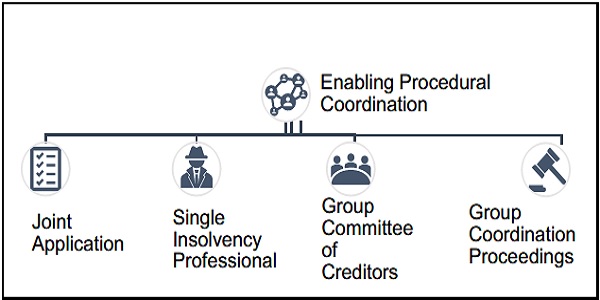

Figure 1: Enabling Procedural Coordination Mechanisms

Based on this approach, the Working Group recommended that a flexible and enabling framework of procedural coordination mechanisms may be provided in the Code, and noted that –

“a. The framework may have the following elements of procedural co-ordination:

i. Joint application

ii. Communication, cooperation and information sharing

iii. Single insolvency professional and single Adjudicating Authority

iv. Creation of a group creditors’ committee, and

v. Group coordination proceedings.

…b. While all other elements of procedural co-ordination may be voluntary, cooperation, communication and information sharing among insolvency professionals, CoC and Adjudicating Authorities may be mandatory for companies that have been admitted into CIRP.”55

The Committee reviewed the above recommendations of the Working Group in respect of the approach to providing procedural coordination mechanisms under the Code. It agreed that, as suggested by the Working Group, the framework for procedural coordination of insolvency proceedings of group companies under the Code should be enabling in nature and flexible enough to be adopted suitably to different kinds of cases. The Committee also agreed that this framework should not be too prescriptive, and should allow parties to negotiate among themselves to arrive at the most commercially viable manner of coordinating the proceedings.

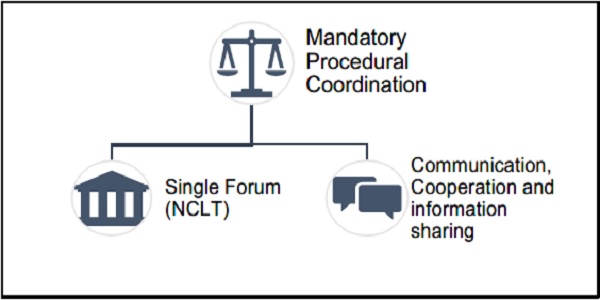

Figure 2: Mandatory Procedural Coordination Mechanisms

The Committee also discussed that the Working Group had rightly identified the appropriate mechanisms for effectively coordinating the administration of insolvency resolution and liquidation proceedings under the Code. Accordingly, the Committee agreed that the following procedural coordination mechanisms should be available to parties in respect of the corporate insolvency resolution and liquidation proceedings of corporate debtors belonging to the same group:

(a) filing of joint application for initiation of the corporate insolvency resolution process;

(b) conducting the proceedings in a common forum, i.e., having a single Adjudicating Authority;

(c) appointing a common insolvency professional;

(d) creating a group committee of creditors;

(e) undertaking communication, cooperation and information sharing; and

(f) holding group coordination proceedings.

Further, the Committee decided that whereas the mechanisms in points (a), (c)-(d) and (f) should be enabling and parties may voluntarily choose to opt for them, the mechanisms in points (b) and (e) should be mandatory. This has been depicted in figures 1 and 2 above, and elaborated on in the following paragraphs.

5.1. Joint application

One of the means of ensuring effective cooperation and coordination of insolvency proceedings of multiple group members is to allow filing of a joint or single application for commencing such proceedings. In this regard, the UNCITRAL Legislative Guide recommends that filing of joint applications should be permitted under the insolvency law, provided that each of the group members “satisfies the applicable commencement standard”.56 According to the UNCITRAL Legislative Guide, a joint application may be filed by two or more group members that meet the applicable commencement standard, or by a creditor of two or more such group members.57

Similarly, the Working Group had recommended that a joint application on behalf of multiple group members should be permitted and that such application may be filed by “financial creditors, operational creditors or the group companies themselves”.58 Further, in line with the recommendations of the UNCITRAL Legislative Guide, the Working Group had clarified that a joint application should only be filed in respect of group companies that have committed a default as per Section 4 of the Code.59 Thus, as a joint application is essentially a common application for initiating CIRP against two or more corporate debtors, the requirement for filing a stand-alone application against a single corporate debtor, namely the existence of default, should also apply for filing a joint application.

During the course of consultations with international experts, the Committee was informed that in the US, a joint application, involving all the members of a corporate group, is typically filed for commencing bankruptcy proceedings against a corporate group. Similarly, the Committee noted that in the UK, an application to commence an administration proceeding against a principal member of a group is typically accompanied by simultaneous applications on behalf of the other members of the same group. Such simultaneous applications are typically filed before the same court and are represented by the same counsel as well.

The Committee noted that there are several advantages in allowing filing of joint applications. It may help in improving efficiency and reducing costs by allowing courts to take a comprehensive and coordinated assessment regarding whether CIRP should be commenced against all the corporate debtors in respect of whom a joint application is filed.60 Further, it may also establish a common date of commencement for multiple group members and help the court to gather information regarding the entire group which may also help in determining whether insolvency proceedings ought to be commenced against the group members involved.61 However, the Committee noted that the UNCITRAL Legislative Guide distinguishes a joint application from other procedural coordination mechanisms: while a joint application helps in coordinating commencement of multiple proceedings and establishing common timelines, it is not intended to pre-determine whether and to what extent such proceedings should be coordinated.62 A joint application may, nevertheless, aid the court in determining whether procedural coordination would be appropriate in a given case.63

Given the advantages of enabling joint applications, and the prevalence of the same in other jurisdictions, the Committee agreed that the Code should permit filing of joint applications on behalf of multiple corporate debtors belonging to the same group, that have committed a default. In other words, joint applications may only be filed against corporate debtors belonging to the same group if each such application meets the requirements of Sections 7, 9 or 10, as may be applicable.

However, the bar against initiation of insolvency proceedings against solvent group members should not preclude such group members from voluntarily contributing towards the resolution of insolvency of other group members. Thus, if a solvent group member wishes to participate in the insolvency resolution of other group members, for helping in the resolution of such group members or to protect its own interests, such voluntary participation should not be restricted. For example, if the liquidation of any one group member may adversely impact the interests of other members of the same group, solvent group members should not be prevented from submitting resolution plans or extending interim finance, to other group members.64 The Committee noted that, internationally, such participation by solvent group members, on a voluntary basis, is “in fact, not unusual in practice”.65 However, as a solvent group member will not be subject to any insolvency proceeding, the decision to participate in the resolution of insolvency of other group members, would be an ordinary business decision of such group member.

The Committee noted that, in some cases, different Adjudicating Authorities may have jurisdiction over the registered offices of different group members, which may preclude the filing of a joint-application. To remove this difficulty, the Committee agreed that the Code should enable filing of a joint-application on behalf of two or more group members, before any Adjudicating Authority which has jurisdiction over any one such group member.

In the context of joint applications, the Committee considered whether the Code should prescribe filing of a combined application form or allow simultaneous filing of separate applications. In this regard, the Committee noted that if the latter approach is adopted, it would allow for the individual group members to separately file for withdrawal under Section 12A, independently appoint or replace resolution professionals, etc. Effectively, this would allow the insolvency proceedings to be conducted separately, with the option of subsequent procedural coordination. Given this, the Committee agreed that while the Code should allow for filing of joint applications on behalf of multiple group members, it should be in the form of separate applications being filed simultaneously on behalf of each such group member. Such simultaneous applications should be accompanied with a common form, which may be prescribed in subordinate legislation. This form should provide relevant details of the financial and operational linkages between the corporate debtors in respect of whom insolvency proceedings are proposed to be initiated. This will enable the Adjudicating Authority to determine whether the such corporate debtors form part of the same ‘group’. It will also facilitate a common listing of cases and a coordinated admission process.

Drafting Instructions (Box 5)

- Filing of joint applications for initiation of corporate insolvency resolution proceedings against multiple corporate debtors belonging to the same group may be permitted.

- Such applications may be filed with an Adjudicating Authority that has jurisdiction over any one of the corporate debtors in respect of whom such joint application is being filed.

- Although filing jointly may be permitted, the application form for each corporate debtor should be separate, but accompanied by a common form.

5.2. Common Forum

Although the question of jurisdiction is often considered relevant only in cross-border cases, conflicts over jurisdiction may also arise domestically. Multiple domestic courts may potentially have jurisdiction over different group companies if such companies are located in different places of the country.66 The question of allowing only a single authority to have jurisdiction over insolvency proceedings of group entities may arise at two stages- first, at the stage of filing application for commencement of insolvency proceedings; and second, at the time of administration of proceedings.

5.2.1. Forum for filing of application for commencement of CIRP