Rajnish Kumar, Chairman, State Bank of India

The Government of India introduced the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (Code) in May 2016 as a consolidated legal framework for time-bound resolution of insolvency and reorganisation of corporate persons, partnership firms and individual firms with the objectives of maximisation of value of assets, promoting entrepreneurship, availability of credit and balancing the interests of all stakeholders.

The Code is one of the most crucial reforms initiated in recent years that represents a paradigm shift for insolvency resolution in India. The Code is a game-changer in the sense that it motivates the management and promoters of firms to avoid default as their inefficiencies to operate above the optimum level may lead to shift in control and management of the firm away from existing promoters and managers. Since the enactment of Code, 2162 cases have been admitted into corporate insolvency resolution process (CIRP). A need has been felt to assess the effectiveness of the Code vis-a-vis other erstwhile legislations. According to data published by Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (IBBI) up to June, 2019, 870 CIRP cases stand closed, out of which 174 were closed on appeal or review or settled, 101 withdrawn, 475 ended in liquidation and 120 concluded with an approved resolution plans. 1292 CIRP cases are still ongoing out of which more than 33 per cent have exceeded the 270 day timeline. This article, undertakes an impact assessment of effectiveness of the Code as a potent tool for resolution. For such an assessment, its performance vis-à-vis other available resolution options can be tested based on parameters such as transparency and protection of creditor rights; improved handling of conflict among stakeholders; changing borrower behaviour; achieving time bound resolution; preservation and maximisation of value of a corporate debtor (CD), recovery vis-à-vis other mechanism; drawing distinction between malfeasance and genuine business failure and predictable and clear allocation of losses.

TRANSPARENCY AND PROTECTION OF CREDITOR RIGHTS

Transparency

CIRP under the Code is a non-adversarial resolution process where the defaulting CD cedes control to a court appointed Resolution Professional (RP). While the RP is responsible for managing the affairs of the firm as a going concern and preservation of its value, the committee of creditors (CoC) is responsible for supervising actions of RPs, take critical decisions in the interest of CD and its early resolution after assessing feasibility and viability of a resolution plan. While deliberations and decisions of CoC are made available to all members of CoC and to some extent other creditors, generally all major actions under the insolvency process such as its initiation, appointment of RP, invitation for resolution plan through expression of interests and approval of resolution plans etc. are available in public domain.

Further proof of transparency under the Code is the day to day reporting of developments in most large insolvency cases in national dailies. Even a common man can access insolvency court orders online. The bidding for assets of a CD are through open market bidding and hence any eligible person can bid as resolution applicant. The number of bids received, and haircuts suffered by creditors under resolution are also available in public domain. Hence, on the test of transparency, the Code outclasses all other options for recovery.

Protection of Creditor’s Rights

Protection of creditor’s rights is a fundamental requirement of credit markets in a market economy and as a rule, the security interest and other real creditor rights created prior to the insolvency proceedings must remain unaffected by the insolvency or liquidation proceedings. The Recovery of Debts Due to Banks and Financial Institutions Act, 1993 (RDDBFI) and the Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Securities Interest Act, 2002 (SARFAESI) regimes protect the rights of only financial creditors (FCs). However, the rights of operational creditors (OCs) other than workmen and employees are generally ignored. The effectiveness of these regimes has been compromised due to multiple litigations by aggrieved creditors/CD and consequent delays.

Inter-Creditor Arrangement (ICA) is another resolution mechanism introduced recently to arrange out of court resolution of insolvency but includes only banks and financial institutions as participants while leaving out other FCs and OCs. It is still too early to judge its effectiveness in protection of creditor rights.

The Code, on the other hand, has brought about fundamental change in the priority ranking of creditors rights by placing sovereign debt and statutory dues at a rank lower than FCs. The Code has also expressly delineated the ranking of creditor rights under a liquidation waterfall (section 53). The Code was however silent on priority ranking of creditors for distribution under a resolution plan. The author is of the opinion that this was deliberately left open to allow normal market practises of distribution waterfall as well as to the commercial judgement of CoC so as to provide greater flexibility for bargaining an optimum sharing arrangement acceptable to majority of creditors and hence approval of plan. However, distribution of resolution amount under various resolution plans were challenged by OCs and unsecured FCs. The insolvency courts misinterpreted the silence of Code to infer that it is an issue left to them to decide by exercising judicial discretion. This resulted in a major interference in creditor rights when National Companies Law Appellate Tribunal (NCLAT) in its judgement in Standard Chartered Bank v. Satish Kr. Gupta, IP Essar Steel, declared that the Code does not discriminate between secured and unsecured creditors in a resolution and also that OCs be treated equal to FCs in the interest of fair and equitable distribution.

This created a situation whereby denial of secured creditor’s real rights in the insolvency process, the court used the very event of insolvency against which security interests were designed as a protection, as a ground for its destruction. Had this interpretation persisted, a major disruption was expected in credit markets. Through a quick amendment to the Code, the Parliament re-established the sanctity of priority ranking of creditor rights by giving a clarification that waterfall provided in section 53 of the Code shall also apply to ranking of distribution under a resolution plan. While this is a welcome step towards protection of rights of secured creditors vis-a-vis unsecured creditor, it still leaves some scope of potential conflict among secured creditors as different types of security rights have to be treated differently. It is envisaged that this will put to rest most disputes arising from unsecured and operational creditors regarding distribution under resolution.

Hence, it may be concluded that while the Code has been very successful in bringing transparency to the resolution process, it achieved only partial success in securing creditor rights.

IMPROVED HANDLING OF CONFLICT BETWEEN STAKEHOLDERS

The Code has improved the scope of managing conflict between creditors and debtors and among the various class of creditors due to its very design. Due to the provision of a calm period (moratorium) immediately on commencement, the Code restrains any individual creditor from taking precipitative action. Through collective CoC mechanism for exploring resolution, the Code has assigned a major fiduciary duty to the CoC to cooperate and follow the prescribed resolution process for seeking a time bound resolution which is equitable and fair to all.

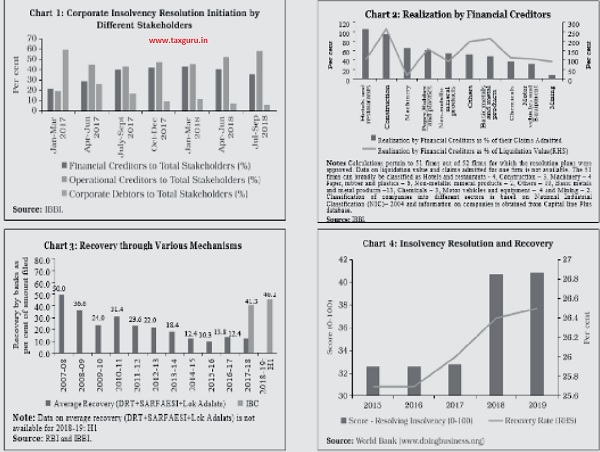

As per data published by IBBI, more than 50 per cent of the CIRP cases were initiated by OCs, around 40 per cent by FCs and only 10 per cent by CDs themselves. It has been observed that in most of the cases settled out of Court, before admission of a CIRP under the Code, an out of court settlement had been reached between the CDs and the OCs and FCs which led to the subsequent withdrawal of the cases.

Thus, it can be inferred that the Code has been effective in improving the bargaining power of both OCs and FCs vis-à-vis the debtor and is becoming the preferred mode of resolution for them.

The author observes that while there have been petitions made by OCs before insolvency courts that their interests were overlooked in the resolution plans, the actual data indicates otherwise. As per IBBI data, the recovery rate of OCs in 97 resolved CIRP cases was approximately 42 per cent of their claims. Part of this may be because workmen are treated at par with secured FCs and employees next in distribution priority. However, going by the number of cases resolved amicably before admission of CIRP or cases withdrawn under section 12A of the Code post-admission on account of out of court resolution, it may reasonably be concluded that the Code has been much more effective than other regimes in resolution of conflicts between the stakeholders.

CHANGING THE BORROWER BEHAVIOUR

Recovery acts such as RDDBFI, SARFAESI and the Sick Industrial Companies (Special Provisions) Act, 1985 (SICA) did not deliver encouraging results and had limited impact on borrower behaviour. Due to inordinate delays at Debt Recovery Tribunals (DRTs), the borrowers became rather comfortable in bank initiating DRT proceedings as they did not have to bother about bank loan till proceedings continued. SARFAESI was successful to some extent in influencing customer behaviour but proved effective only in smaller debts. Due to its provisions of unlimited moratorium, Board for Financial Reconstruction (BIFR) under SICA was used as a legal shelter by defaulting borrowers to stall recovery proceedings while they continued to maintain control over assets. Hence, the best available options for banks before the advent of the Code were either to enter into a compromise with borrower or sell the asset to an Asset Reconstruction Company (ARC) at high discount on deferred payment terms. Even in compromise proposal, the borrowers had upper hand in negotiations due to time involved in recovery under other alternatives.

Post introduction of the Code, a perceptible change in borrower behaviour has been observed. Now many borrowers are approaching the banks with reasonable settlement offers. Some of them come forward due to fear of losing control of their business. This is also reflected in the better recovery rates of most of the banks. In the case of State Bank of India (SBI), the recovery during FY2019 was more than double the recovery during FY2018. The contribution of the Code in this recovery was 37 per cent and compromise settlements at approximately 16 per cent. Hence, based on the experience of better recovery during last two years, the Code has proved to be very effective in bringing about a positive change in borrower behaviour.

Source: RBI Report on Trends and Progress of Banking, 2017-18

ACHIEVING TIME BOUND RESOLUTION

Under the Code, a defaulting firm has 180 days extendable to maximum 270 days from date of admission to resolve its default. Within such time, if the CoC does not agree to a resolution plan or no resolution plan is received, the company goes into compulsory liquidation. This deadline was meant to be sacrosanct given that it is specified in Code and time-bound resolution mentioned as one of the primary objective in the preamble. The Code also stipulated time-bound admission within 14 days from the filing of a CIRP application.

But this objective has often remained unmet. IBBI data shows that 445 pending cases have crossed the 270-day deadline. Of the 12 large accounts referred to insolvency by banks, under directions of the Reserve Bank of India in June 2017, resolutions have been approved in only six cases so far. These are high-value cases, adding up to an outstanding claim of Rs 3.45 lakh crore, and yet they have been dragging. As an example, Essar Steel Ltd. has now been in the insolvency process for close to 700 days and Bhushan Power & Steel Ltd. for over 650. Among the six cases that have been resolved, many have still exceeded the 270 day deadline. There have been numerous cases filed with NCLTs which are yet to be admitted. For example, SBI has 123 cases where CIRP has not been admitted even after three months after filing. Out of these 123 cases, 3 cases have been pending for admission for more than 18 months; and in 25 cases, anywhere between 12-18 months.

Many cases are pending for approval of resolution plans with NCLTs. SBI has around 38 cases where approval of resolution plans is pending for approval and another 55 cases where liquidation orders are awaited. One reason for this delay is that insolvency courts entertaining multiple interim applications on petty issues and devoting multiple hearings to such matters. However, the insolvency courts appear to be adopting processes similar to Civil Procedure Code, 1908. The Code is designed on the principle that CIRP is not against the CD and there are no defendants or plaintiffs. It is a collective mechanism where financial creditors, through the institution of CoC apply their technical expertise to work out a viable and feasible resolution. CoC is also the forum for resolving inter-creditor conflicts. However, insolvency courts, by giving multiple hearings to arguments, seem to have failed to maintain the spirit of time bound and collective resolution inherent in the Code. Such delays result in many uncertainties and higher risk, specifically for buyers of stressed assets and lead to substantial erosion in the value of assets. During the insolvency, the industry itself can undergo a change and it has corresponding impact on valuation of the CD. The steel industry, for example, is not in as robust condition today as it was one year ago and such delays may lead to the bidder losing interest in resolution or having second thoughts about the value of its investment.

It needs to be appreciated that the Code is a new law and it takes time for jurisprudence to develop. The delay in some large cases can be attributed to various legal questions and principles being settled before courts and tribunals. However, the jurisprudence around Code has developed at a rather fast pace with Hon’ble Supreme Court providing very frequent and valuable clarifications on different aspects of Code. Accordingly, with availability of greater clarity on various provisions of Code, combined with proactive stance of Government and IBBI in quickly tackling issues arising out of ongoing cases, there is confidence among the stakeholders that the CIRP will become more efficient and will close much before the given timelines in future cases.

PRESERVATION/MAXIMISATION OF VALUE

While the SICA was not able to achieve preservation of value during resolution, the RDDBFI and SARFAESI, by their very nature of being recovery acts, were expected to only maximise recovery and not value of the enterprise. The Code, on the other hand, was drafted with the objective of preservation or maximisation of value of CD during CIRP. In some large cases like Bhushan Steel, Essar Steel etc., there was an improvement in the turnover and EBITDA (Earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation) during CIRP leading to enhancement of value. But in most of the other cases, the value of assets has deteriorated on account of delays by the NCLTs in admission of CIRP, in approving resolution plans or even in ordering liquidations.

Approximately 80 per cent of CIRP cases have ended in liquidation and recovery through liquidation so far is insignificant with many liquidation cases still under process. With recent amendment to IBBI( Liquidation Process) Regulations, 2016 reducing process time to one year, it is hoped that the liquidation process will yield better value and in shorter time. Cost of CIRP or liquidation process are also considerably higher than other recovery mechanisms. However, if we compare it with erosion of values due to inordinate delays under RDDBFI and SARFAESI, and better recovery rates under the Code, the same can be justified. Overall, the impact of the Code in preservation and maximisation of value may be considered partially effective.

Recovery visa vis other Mechanisms

While recovery is not the objective of the Code, it remains one of the relevant factors for the FCs while deliberating a resolution plan. As may be seen from chart 3, the average recovery through the Code during 2017-18 was 41.3 per cent and HY2018-19 was 46.1 per cent. This is much higher than the average recovery of 12.4 per cent achieved through the DRT process, SARFAESI and Lok Adalats during 2017-18. It is also apparent that recovery through other mechanisms is a case of diminishing returns with recoveries coming down every year. If the average time of resolution under the Code, which is around 300 days vis a vis 2-3 years under SARFAESI and 7-9 years under DRT process is taken into consideration, as has been mentioned in the section above, it is possible to conclude that the Code has been very effective in achieving better recoveries in shorter time compared to other options

DRAWING A LINE BETWEEN MALFEASANCE AND GENUINE BUSINESS FAILURE

Under RDDBFI and SARFAESI, the focus is on recovery and there are no provisions for any enquiry into fraud/malfeasance by the promoters leading to insolvency. Hence, it is always difficult to decide whether insolvency was due to some genuine business failure or due to any fraudulent dealings/transactions. However, the Code provides (sections 43, 45, 49, 50) for examination of any such avoidance during the look back period of 1-2 years. Further fraudulent transaction or wrongful trading does not have any limitation of look back period. Thus, the Code provides a well-defined mechanism to bring such unscrupulous promoters who came under the purview of these provisions to enforce recovery for such amounts from their personal assets and also impose criminal penalties. This unique feature of the Code makes it a potent and an effective law. Hence, the Code has been effective in providing a mechanism where the genuine defaulters get another chance and unscrupulous promoters are kept out of credit markets.

Predictable and clear allocation of losses

A limited company is an organisation wherein the liability of the company is limited by its equity and losses higher than equity value are borne by the creditors. Hence, to maintain confidence in credit markets, any insolvency law must provide clear guidance for allocation of losses. In other recovery options under RDDBFI and SARFAESI, any liability over and above the liquidation value of assets is covered through enforcing collaterals securities and guarantees. However, since the entire value is captured by FCs, maximum losses are allocated to OCs and then FCs by way of haircuts. The Code has provided a clear and predictable waterfall arrangement for allocation of losses. As per the experience of law two and half years, the Code has been very effective in allocation of losses as per liquidation waterfall. However, allocation of losses in resolution plans was challenged by OCs and NCLAT also upheld their stance. But the Government has put to rest all such doubts by providing clarification on intent of the Code through a third amendment to the Code. Hence, in providing predictable and clear allocation of losses, the Code has been highly effective.

CONCLUSION

It can be concluded that the Code has delivered a potent tool in the hands of creditors for quick and flexible resolution and despite several issues faced in its implementation due to novelty of the law, infrastructural weakness, underdeveloped ecosystem and slowdown in the economy, the Code has performed beyond expectations of the stakeholders. Being a new and dynamic law, it will continue to evolve and litigated, but has proved its worth as an effective mechanism for resolution of insolvent businesses.

Notes:-

1Company Appeal (AT) (Ins.) No. 242 of 2019

Source- https://ibbi.gov.in/uploads/whatsnew/2456194a119394217a926e595b537437.pdf