Dr. Rajiv Mani*

‘We are happy to note that in the working of the Code, the flow of financial resource to the commercial sector in India has increased exponentially as a result of financial debts being repaid……………….. The defaulter’s paradise is lost. In its place, the economy’s rightful position has been regained.’

Epilogue, Swiss Ribbons Pvt. Ltd. & Anr. v. Union of India & Ors. 1

The above observations of the Supreme Court succinctly sum up the gains from the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (Code). They bear witness to the well-known adage that efficient and predictable insolvency and debt resolution frameworks are key drivers to increased access to credit, reduction of the cost of credit and efficient allocation of scarce capital resources of an economy.

While this modern legislation is working towards bringing a paradigm shift in the manner of resolution of distressed firms in the country, it is important to note that the practice of recovery of debt from the person of the debtor has been a common practice since the inception of insolvency law. Though the law in every region has had its own mode of evolution, this practice of recovery can be found in most of the depicts of law. It was a debtor himself and his family members (and not a debtor’s property) that formed a debt insurance guarantee.

We dwell here on some interesting aspects of the ‘law of debt’, as was in ancient India.

The Dharamashastras are the collection of important Smiriti texts. Smritis were authored by the sages in ancient times and are a repository of the body of rules which gave form and steps to the Hindu Law-a law that catered to the needs of the multitudinous population of the sub-continent from ancient times till the statutory laws amended them.

The concept of debt and its repayment had been a major area wherein, Smritikars had commented upon this obligation and its discharge. It is needless to say that the modern laws and the present judicial system have equally maintained the importance of this area in the administration of justice and the Code is a manifest example of the same.

Law of debt is a very important branch of ancient Hindu Law. It has been emphasized that is the legal as well as the moral duty of a person to pay his debts. The Dharmashatras go to the extent that the non-payment of debt is a positive sin. Therefore, if a person dies indebted to any person, the rewards of the good deeds of the former are transferred to the latter. The concept was that the unpaid debt will have to be paid in the next life by serving the creditor as slave or as a beast and this will have to be done life after life, until the debt is fully discharged. A person cannot get salvation unless the debt incurred by him is repaid by himself or some other person on his behalf.

In addition to the borrower, the following other persons are liable to pay his debts : (i) Heirs, (ii) Coparceners, (iii) Principal, and (iv) Son.

Dharamshastras also provided that the person taking the estate of the deceased is liable to pay his debts. Similarly, a debt contracted by a coparcener shall be repaid by other coparceners and further the debts incurred by an agent or representative of family for family purposes is to be paid by family members.

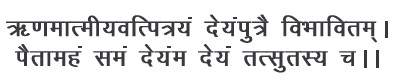

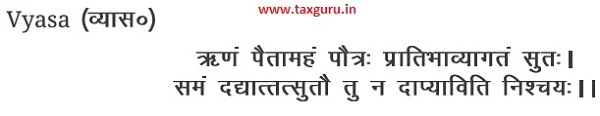

Lastly a son under Hindu law is under obligation to repay his father’s debts. This obligation is irrespective of his inheriting any property from the deceased father. This is known as the ‘pious obligation’ of the son. This provision has been made so that father may not go to ‘narak‘ (hell) for non-payment of his debt. The term ‘son’ included grandson and great grandson also. As regards the possibility the father’s debt is to be paid before one’s own debt and great grandfather’s debt before either of these. A son is liable to pay the debt of his father like his own debt. The grandson is to pay the debt of his grandfather without interest but the grandson shall not be compelled to discharge the debt of his great grandfather unless he is an heir and has assets. There is no obligation to repay that ancestral debt which is unconscionable or avyavaharika (immoral).

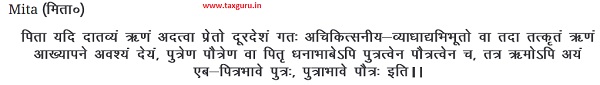

The obligation of discharging the debt generally arises on the death of the debtor ancestor, but in certain circumstances, it arises even during his life time i.e. when the father goes to distant place, or is afflicted with an incurable disease etc. However, as stated earlier debt incurred for immoral purpose or avyavaharika debts are not payable. Thus avyavaharika debt is that debt, the recovery of which could not be enforced through law.

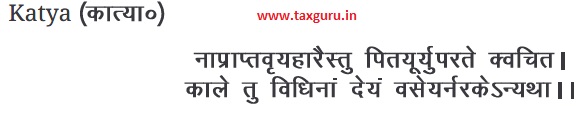

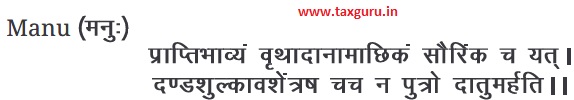

Also, the money due on account of ‘surety ship’, or lost at play, or due to for spirituous liquor, or promise made without any consideration, or under the influence of lust, or of wrath or for purpose repugnant to good moral, unpaid fine, tax or duty, and also the debts which are avyavaharika are not to be paid by the son.

The Concept of Surety

‘Surety ship’ is of four kinds: for appearance, for honesty, for payment, and for delivering the assets of the debtors.

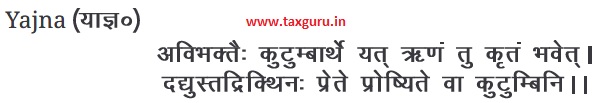

The son is under no duty to discharge the obligation(s) arising from the first two kinds of surety ships, but the obligation incurred by the last two kinds binds the son also. Agreements entered into or transaction(s) made by an intoxicated, insane, wholly dependent infant or a very aged person or which are contrary to law or settled usage or are fraudulent or caused by force were treated invalid. A wife and husband and mother and son were not mutually liable for the debt of each other unless it is contracted on account of family. A father is not liable for the debt of his son, unless it is incurred for family purposes or is contracted in time of distress. Given the concept of debt and the importance attached to its repayment in the Dharmashastras, it is relevant to highlight the texts of the Smritikars who have commented upon the subject. Some of the important learnings from the Smritikars are encapsulated here2

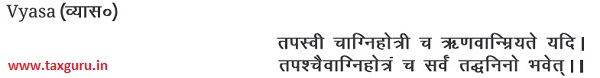

When a person, being either an ascetic, or keeper of a perpetual fire, dies indebted to any one, the future rewards of the austerities of the one, and the sacred duties of the other, shall all be transferred to the account of the account of the creditor. (quoted in Smriti Chandrika 161)

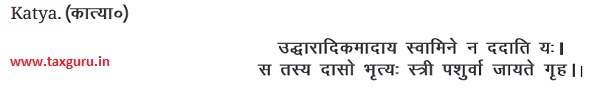

He who shall not pay to his creditor what he has received from him in loan (uddhara) or other way, shall most certainly be born again, either as his slave, servant, wife, or beast of burden.

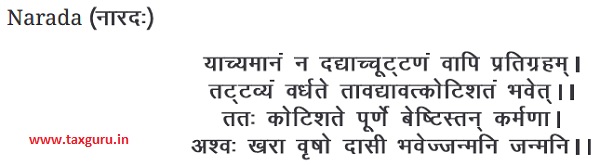

If a man does not repay what he has borrowed for use, and a debt, as well as what he has promised, that sum may be increased, even to ten million times its original amount. And after that, if it be allowed to increase still more, until by its own accumulation it has amounted to a hundred (times) ten million, it must then stop, the debtor shall become, in each successive birth, a horse, an ass, a bullock, and a slave. (IV.7-8)

Persons Taking the Estate of Deceased to Pay his Debts

They who share the inheritance must pay the debts (XXIX.7)

He who takes the estate of one whether leaving a son or no male issue must pay his debts. (VI.’9)

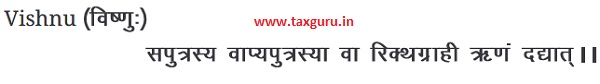

He who has received the estate, must pay the debts of it, and in like manner, he who takes the wife (of the deceased), or the son, whose (father’s) assets are not held by another (ananyashrita), but of one having no son, the other heirs (rikthinahi), must pay the debts; or may levy them (II.51)

Coparceners to Pay the Debt of a Deceased Coparcener

A debt contracted by coparceners shall be paid by any one of them who is present (VI.34)

The debt that has been contracted by unseparated members of the family, for purposes of the family, shall be paid by the coparceners, when the head of the family is dead or gone abroad (II.45).

Debts Incurred by an Agent or Representative of Family for Family Purposes to be Paid

And (so must be (the householder) pay that debt) which was contracted by and person for the behalf of the family. (VI.39)

And (so must be (the householder) pay that debt) which was contracted by and person for the behalf of the family. (VI.39)

If the debtor be dead and (the money borrowed) was expended for the family, it must be paid by the relatives out of their own estate even if they are divided. (VIII.166)

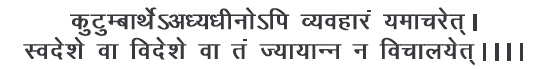

A transaction for the benefit of family, even though effected by a servant, should not be repudiated by the master, whether in his own country or abroad. (VIII. 167)

Debts incurred for domestic uses, by the salve, wife, mother, or disciple, of one gone to a far country, or deceased, and also by his son, must be paid so says Bhrigu. (See Aprarka, II. 46)

Pious Obligation to Pay Debts Insured by One’s Ancestors

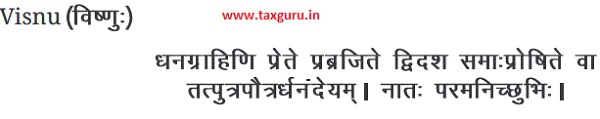

If he who contracted the debt should die, or become a religious ascetic, or remain abroad for twenty years, that debt shall be discharged by his sons or grandsons. But not by remote descendants against their will. (VI. 27-28)

And so shall the debt of the father (be paid) by (any one of ) the brothers (or of their sons) before partition.

But after partition they shall severally pay according to their shares of the inheritance. (VI. 35-36)

The father being dead, or gone abroad, or laid up with an incurable disease, the debt, proved in case of denial, is to be paid by the sons and grandsons. (II. 50)

Therefore by a son born, in disregard of this personal interest, is the father to be diligently liberated from debt, so that he (the father) may not go to ‘naraka‘ (hell). (II. 6)

The father being, dead, his sons, whether after partition or before it, shall discharge his debt in proportion to their shares; or that son alone who has taken the burden upon himself. (I. 14)

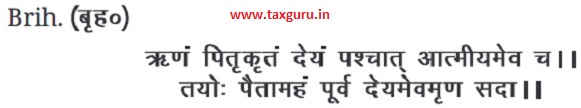

Father’s debt is to be paid (first), one’s own afterwards, but the debt of the paternal grandfather must even be paid before either of those. (quoted in Aprarka, II.50)

The sons must pay the debt of their father, when proved, as it were their own (that is, with interest) the son’s son must pay the debt of his grandfather (but) without interest; and his son (that is, the great-grandsons) shall not be compelled to discharge it (unless he be heir, and have assets). (quoted in Mita. 11.50)

If any debt exists against the father, his son shall not take possession of his effects. They must be given to his creditors, and if he dies without wealth, still his son must pay his debts. (quoted in Smriti Chandrika 169)

The son of a son shall (in general) pay the debt of his grandfather, but the son (only) shall pay the debt of his father incurred by his becoming a surety, (and both of them) without interest; but is clearly settled, that their sons (the great-grandson and grandson respectively) are not (normally) bound to pay. (quoted in Sen P. N. General Principles of Hindu jurisprudence p. 323).

If the father, without having paid the debt which he is liable to pay, has gone to a distant place, or is affected with an incurable disease etc., then the debt contracted by him must be paid by the son or the grandson, even if there is no property of the father (in their possession). They must pay because they are son or grandson. And this is the order (of the liability)-son has to pay in the absence of the father, and the grandson in the absence of the son. (11.50)

The Obligation to be Enforced when Son becomes Major

The duty to pay off the father’s debt does not create an enforceable obligation until the son attains majority, and so the creditor’s right to sue him is till then postponed. (quoted in Aprarka, 11.50)

Immoral Debts of the Father not to be Paid by the Son

But money due by a surety, or idly promised, or lost at play, or due for spirituous liquor, or what remains unpaid of a fine and a tax or duty, the son (of the party owing it) shall not be obliged to pay. (V11.159)

Debt contracted by the father for purposes of spirituous liquors, prostitution, and gambling unpaid fines and tolls, as also debt for promises without consideration-these the son may not pay. (11.47)

Notes:-

1(2019) 4 SCC 17

2 Compiled from: Mani B. N. (1989). Laws of Dharmashastras. South Asia Books.

Source- https://ibbi.gov.in/uploads/whatsnew/2456194a119394217a926e595b537437.pdf

*(Dr. Rajiv Mani is a Joint Secretary and Legal Adviser, Department of Legal Affairs, Ministry of Law and Justice, Government of India and an ex-officio Member of IBBI.)