The Committee of Experts has submitted its report on Regulating audit firms and the Networks to the Government of India through the Secretary, Ministry of Corporate Affairs. The Committee was constituted on April 20, 2018 pursuant to the directions of the Hon’ble Supreme Court in the matter of S. Sukumar versus The Secretary, Institute of Chartered Accountants of India. The Committee consisted of Shri Anurag Agarwal, Joint Secretary, Ministry of Corporate Affairs, Shri Sudhanshu Pandey, Additional Secretary, Department of Commerce and Shri Ravinder, Joint Secretary, Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion.

The report addresses the issues raised by the Supreme Court with a focus to strengthen the legal regime of auditors and promote development of the audit profession in the country. The Committee scrutinised the networking arrangements adopted by the big four audit firms commonly referred as multi-national accounting firms to understand their legal structure and method of operation. The Committee also addressed serious concerns like conflict of interest and transparency arising out of non-audit services provided by auditors and their network, and suggested necessary checks and balances. Further, the report deals with the issue of concentration of market power which is another contemporary problem in the market for audit services.

The global trend indicates a clear shift from self-regulation to independent regulatory structure in the domain of audit regulation due to the failure of self-regulatory model in regulating the professionals. In light of these developments, the Committee found establishment of the National Financial Reporting Authority (NFRA) as a necessary institutional reform which would align the Indian audit landscape with the global position. The Committee also recommended measures to further strengthen the operation of NFRA to address contemporary challenges in relation to auditors, audit firms and networks operating in India.

Since it is important to facilitate a business friendly environment for corporate and professionals in India, Indian laws and regulations on professional services needs to keep pace with changing market dynamics. Taking note of this requirement, the report delves into critical issues like advertising, multi-disciplinary practice firms and branding and suggested measures to rationalise the existing laws. These measures are expected to not only enhance the standards of services offered to corporates, but also facilitate the audit firms to expand in size and operation to compete globally.

For arriving at the findings and recommendations, the Committee adopted a holistic methodology which included internal meetings, engagement with relevant stakeholders, examining past reports discussed in the Supreme Court’s judgment, global literature and best practices in the auditing landscape.

The Committee was ably supported by the research work of the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy.

—————————-

Full Text of the Report is as follows:-

Report

October 25, 2018

Constituted by

MINISTRY OF CORPORATE AFFAIRS, GOVERNMENT OF INDIA

COMMITTEE OF EXPERTS ON REGULATING AUDIT

FIRMS AND THE NETWORKS

New Delhi

October 25, 2018

The Secretary

Ministry of Corporate Affairs

Government of India

New Delhi 110001

Dear Sir,

The Committee of Experts to look into the regulating audit firms and the net-works presents its report to the government. The findings and recommendations aim to address the issues raised by the Hon’ble Supreme Court in its judgement in S. Sukumar versus The Secretary, Institute of Chartered Accountants of India (February 23, 2018) with a focus to strengthen the legal regime of auditors and promote development of the audit profession in the country.

Yours sincerely,

Contents

Executive Summary

1. Background

1.1. Methodology followed

1.2. Structure of report

2. Role of auditors and their regulation

2.1. The basic problem

2.2. Auditors resolve agency problems

2.3. Concerns about auditors

2.4. Rationale for regulation

3. Global developments and best practices

3.1. United States of America

3.2. United Kingdom

3.3. China

3.4. Indian developments

3.4.1. Enron fallout: 2002-2009

3.4.2. Post Satyam: 2009-2013

3.4.3. New Companies Act: 2013 – 2018

4. Issues, findings and recommendations

4. 1. Whether India has an appropriate mechanism for oversight of the audit profession?

4.2. What structures are used by networks operating in India?

4.3. Whether Indian network firms are governed or controlled from outside India?

4.4. Whether Indian network firms should be allowed to use the brand name of the network?

4.5. Should Chartered Accountants and firms be allowed to advertise?

4.6. Should auditors, firms and networks be prohibited from providing non-audit services to auditee companies?

4.7. Is the current Indian legal regime of liability of auditors, audit firms and the networks adequate?

4.8. Whether network firms violate section 25 of the Chartered Ac- countants Act, 1949?

4.9. Whether audit firms by being members of international net- works violate the reciprocity requirement under section 29 of the Chartered Accountants Act, 1949? 85

4.10. What measures could be taken to promote multi-disciplinary practice firms?

4.11. How should FEMA and its regulations be enforced on auditors, firms and networks?

Bibliography

Appendices

A. Annexure A – Supreme Court Judgment

B. Annexure B – Government order establishing the Committee of Experts

C. Annexure C – Dates of Committee of Experts Meeting

D. Annexure D – Stakeholders Questionnaire

E. Annexure E – List of Stakeholders

F. Annexure F – Supreme Court extension order

List of Tables

3.1. Important milestones in Indian auditing landscape

4.1. Comparison of prohibited non-audit services

4.3. Chartered Accountants Act 1949

4.4. Companies Act 2013

List of Figures

3.1. Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) and Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB)

3.2. United Kingdom: Financial Reporting Council

4.1. Type 1 Network

4.2. Type 2 Network

4.3. Type 3 Network

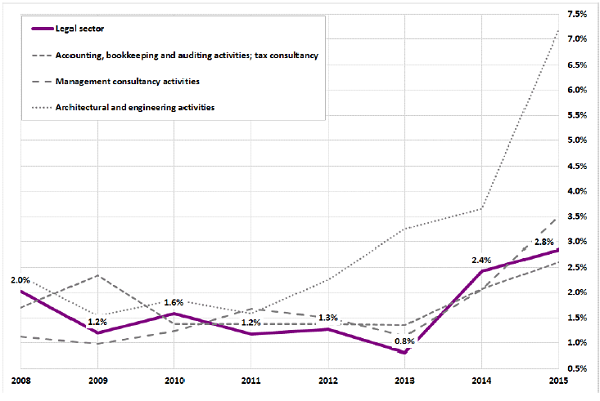

4.4. Total net capital expenditure as a percentage of annual turnover (ONS, UK Wide) for selected service industries (Source: Legal Services Board)

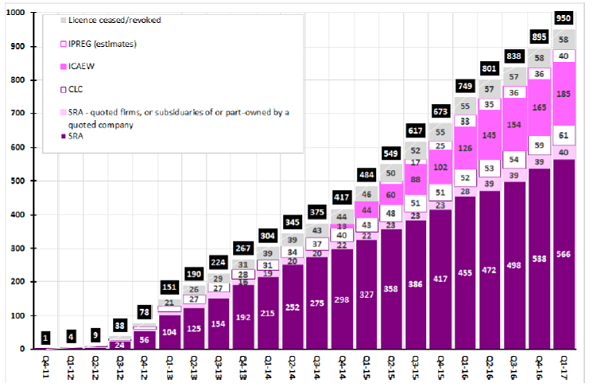

4.5. The growth in the number of ABS licences (Source: Legal Services Board)

Acknowledgement

I am grateful to members of the Committee of Experts (COE) Mr. Sudhanshu Pandey, Additional Secretary, Ministry of Commerce and Industry, and Mr. Ravinder, Joint Secretary, Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion, Ministry of Commerce and Industry for their sincere and valuable contribution. The task of putting together the key issues, suggesting policy options and developing the rationale for the final recommendations would not have been possible without them.

During the consultation meetings, the COE met several stakeholders comprising audit firms, individual chartered accountants, industry associations, professional institutes and experts from the industry. I am thankful to Mr. Yogesh Sharma and Mr. Rajan Vaidyan from MSKA & Associates, Mr. P. R. Ramesh and Mr. K Sai Ram from Deloitte Haskins & Sells LLP, Mr. Harinderjit Singh and Ms. Sharmila A. Karve from Price WaterHouse Chartered Accountants LLP, Mr. Raj Agarwal and Mr. Sudhir Soni from S.R. Batliboi & Co. LLP, Mr. Kaushal Kishore, Mr. Sanjiv Chaudhary and Mr. Ashish Bansal from BSR & Co. LLP, Ms. Pallavi Dinodia Gupta from S R Dinodia & Co Chartered Accountants, Ms. Abha Seth, Mr. Chandrapal and Mr. Mahesh from Federation of Indian chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI), Mr. Marut Sen Gupta and Mr. Vikkas Mohan from Confideration of Indian Industry (CII), Mr. Anil Khaitan from PHD Chambers of Commerce and Industry, Mr. Anil Bhardwaj from Federation of Indian Micro and Small and Medium Enterprises, Mr. Mritunjay Kapur and Mr. Narinder Wadhwa and Mr. Santosh Parashar from Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry of India (ASSOCHAM), Mr. Deepak Bhalla from Infosys, Mr. Manjeet Bijlani from Edelweiss, Mr. Barindra Sanyal from Tata Consultancy Services, Mr. Sanjay Mathur from Marut Suzuki, Mr. J K Jain, DCM Shriram Limited, Mr. Vinod Jain, Mr. Naresh Chand Maheshwari and Mr. Vaibhav Jain from All India Chartered Accountants Society, Mr. V. Sagar from Institute of Chartered Accountants of India (ICAI), Mr. L. Gurumurthy and Mr. S.L. Gupta and Ms. Indu Sharma from Institute of Cost Accountants of India (ICOAI), Mr. Dinesh C. Arora and Ms. Deepa Khatri from Institute of Company Secretaries of India (IC SI), Mr. Russell Guthrie from International Federation of Accountants (IFAC), Mr. Brian Hunt from International Forum of Independent Audit Regulators (IFIAR). They all have contributed valuable insights which translated into rich input for the COE.

The COE acknowledges the assistance received from Mr. G. Vaidheeswaran, Deputy Secretary and Mr. Rakesh Kumar, Under Secretary at the Ministry of Corporate Affairs (MCA).

The COE was ably supported by the research work of the team at National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP) comprising Mr. Pratik Datta, Mr. Sudipto Banerjee, Mr. Shubho Roy, Ms. Shefali Malhotra and Prof. Renuka Sane. I appreciate and acknowledge their contribution to this report.

October 25, 2018

Anurag Agarwal

Acronyms

AAPA American Association of Public Accountants.

ABS Alternative Business Structures.

ADR American Depository Receipt.

AICPA American Institute of Certified Public Accountant.

APESB Accounting Professional and Ethical Standards Board.

ASSUCHAM Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry of India.

BUD Board of Discipline.

CA Chartered Accountant.

CICPA Chinese Institute of Certified Public Accountants.

CII Confideration of Indian Industry.

CMA Competition and Markets Authority.

CUE Committee of Experts.

CPA Certified Public Accountant.

CSRC Chinese Securities Regulatory Commission.

DC Disciplinary Committee.

DD Director of Discipline.

FASB Financial Accounting Standards Board.

FDI Foreign Direct Investment.

FICCI Federation of Indian chambers of Commerce and Industry.

FRC Financial Reporting Council.

FTC Federal Trade Commission.

IBBI Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India.

ICA Italian Competition Authority.

ICAI Institute of Chartered Accountants of India.

ICUAI Institute of Cost Accountants of India.

ICSI Institute of Company Secretaries of India.

IESBA International Ethics Standards Board for Accountants.

IFAC International Federation of Accountants.

IFIAR International Forum of Independent Audit Regulators.

IFRS International Financial Reporting Standards.

IPA Insolvency Professional Agency.

IPO Intial Public Offering.

LLP Limited Liability Partnership.

LSB Legal Services Board.

MAF Multi-national Accounting Firm.

MCA Ministry of Corporate Affairs.

MDP Multi Disciplinary Practice.

MHA Ministry of Home Affairs.

MoU Memorandum of Understanding.

MRA Mutual Recognition Agreement.

NACAAS National Advisory Committee on Accounting and Auditing Standards.

NACAS National Advisory Committee on Accounting Standards.

NFRA National Financial Reporting Authority.

NIPFP National Institute of Public Finance and Policy.

PCAOB Public Company Accounting Oversight Board.

PIE Public Interest Entity.

PW Price Waterhouse.

QRB Quality Review Board.

RBI Reserve Bank of India.

RQB Recognised Qualification Body.

RSB Recognised Supervisory Body.

SEBI Securities and Exchange Board of India.

SEC Securities Exchange Commission.

SILF Society of Indian Law Firms.

SRO Self-Regulatory Organisation.

Executive Summary

Auditors are to resolve agency problems. Moreover, independent audits are fundamental to taking informed and correct investment decisions. Availability of trustworthy financial information on the performance of companies is important to proper functioning of market economy. Serious concerns arise if auditors’ independence is compromised or the trust reposed on them is betrayed.

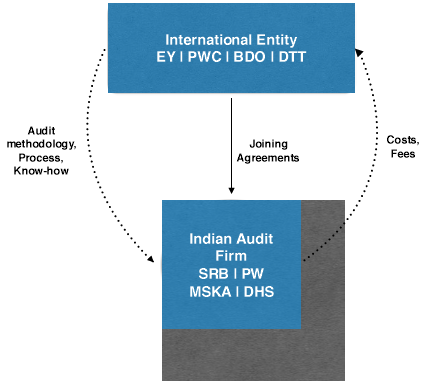

Determining whether an auditor is independent in fact as well as in appearance is complex. This is especially so because audit firms across jurisdictions often provide services as part of one common ‘network’. Consequently, separate firms belonging to the same network could provide audit as well as non-audit services to the same audit client or its holding company or subsidiaries across the same or different countries. This can give rise to the problem of conflict of interest where independence of the auditor may be compromised. Therefore, measures like sufficient disclosure on total fees, imposing cap on non-audit fees from the audit client, revisiting the scope of prohibited non-audit services are needed to address the issue of conflict of interest, especially at the network level.

These networking arrangements also create an impression that the Indian audit firms which are affiliated with these international networks constitute Multi-national Accounting Firms (MAFs). However, on closer scrutiny it turns out that these Indian audit firms are set up as partnerships or Limited Liability Partnerships (LLPs) under Indian laws and all their partners are members of the ICAI. Therefore, there is neither any violation of section 29 (reciprocity) nor any violation of section 25 (companies not to engage in accountancy) of the Chartered Accountants Act, 1949. Neither can such Indian audit firms be simply be equated to multi-national corporations. Consequently, the term ‘MAF’ is a misnomer.

However, such Indian audit firms admittedly follow various internal processes, policies and methodology adopted by their respective networks internationally. This is aimed at maintaining consistent standards in audit quality globally within a network. While such networks bring better business opportunities in a global economy, they should be subject to necessary checks and balances.

Legal measures need to be supplemented with adequate institutional reforms.

Time and again corporate scandals and accounting frauds have nudged insti-tutional reforms across jurisdictions. One such fundamental reform that has happened globally in the last two decades is a shift away from the Self-Regulatory Organisation (SRO) model towards an independent regulatory structure for the audit profession.

In the aftermath of Enron, the U.S. enacted the Sarbanes Oxley Act, 2002. The Supreme Court in its judgment dated February 23, 2018 has referred to this statute to examine the need of an oversight mechanism for the audit profession. This law inter alia provided for the setting up of the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) as an independent audit regulator to oversee the audits of public companies. Similarly, U.K., also has a two-tier structure, where the Financial Reporting Council (FRC) is the independent regulator for the audit profession.

In the Indian context, the Satyam incident has been a wake-up call for policy-makers. Pursuant to the global trend of shift from SRO model to an independent regulatory model for audit profession, the Companies Act, 2013 provided for the setting up of the National Financial Reporting Authority (NFRA).

However, the continued opposition to the establishment of NFRA has delayed the implementation of this critical reform. Consequently, although Companies Act, 2013 was enacted in August 2013, the section establishing NFRA was notified only on March 21, 2018 along with the NFRA Chairperson and Members Appointment Rules, 2018. Once NFRA becomes fully operational, it will be adequately equipped to handle the contemporary challenges in relation to auditors, audit firms and networks operating in India.

Finally, it is important to facilitate a business-friendly environment for corpo-rates as well as professionals in India. It is therefore vital that Indian laws and regulations on professional services keep pace with changing market dynamics. Opening up professional services to competition is necessary and therefore, audit firms should be allowed to advertise with some restrictions. Further, in a global economy use of international brand names for audit firms must be allowed. Laws must be rationalised to promote Multi Disciplinary Practices (MDPs) to allow firms to offer a bouquet of high quality professional services at par with international standards. The Advocates Act, 1961 needs to be rationalised to facilitate development of Indian law firms as well as Indian audit firms into MDPs. Adopting these three measures i.e., advertising, branding and MDPs will not only enhance the standards of services offered to corporates, but also facilitate the audit firms to expand in size/operation enabling them to compete internationally.

1 .Background

The Hon’ble Supreme Court of India vide its judgment dated February 23, 2018 in the matter of S. Sukumar v. The Secretary, Institute of Chartered Accountants of India & Ors. (Civil Appeal No. 2422 of 2018) issued the following direction to the Union of India:

The Union of India may constitute a three member Committee of experts to look into the question whether and to what extent the statutory framework to enforce the letter and spirit of Sections 25 and 29 of the CA Act and the statutory Code of Conduct for the CAs requires revisit so as to appropriately discipline and regulate MAFs.The Committee may also consider the need for an appropriate legislation on the pattern of Sarbanes Oxley Act, 2002 and Dodd Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, 2010 in US or any other appropriate mechanism for oversight of profession of the auditors. Question whether on account of conflict of interest of auditors with consultants, the auditors profession may need an exclusive oversight body may be examined. The Committee may examine the Study Group and the Expert Group Reports referred to above, apart from any other material. It may also consider steps for effective enforcement of the provisions of the FDI policy and the FEMA Regulations referred to above. It may identify the remedial measures which may then be considered by appropriate authorities. The Committee may call for suggestions from all concerned. Such Committee may be constituted within two months. Report of the Committee may be submitted within three months thereafter. The UOI may take further action after due consideration of such report.

The judgment is available at Annexure A. Pursuant to the aforesaid direc-tions, the Ministry of Corporate Affairs, Government of India, set up this Committee of Experts (‘the COE’) vide Office Memorandum dated April 20, 2018 comprising Mr. Anurag Agarwal, Joint Secretary, Ministry of Corporate Affairs (Chairperson); Mr. Sudhanshu Pandey, Additional Secretary, Ministry of Commerce and Industry (Member); and Mr. Ravinder, Joint Secretary, Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion, Ministry of Commerce and Industry (Member). A copy of the aforesaid Office Memorandum is annexed as Annex’ure B.

1.1. Methodology followed

The CUE adopted a holistic methodology including internal meetings, engage-ment with stakeholders, examining past reports discussed in the Supreme Court’s judgment, global literature and best practices in the auditing landscape.

The CUE met nine times including three stakeholder consultation meetings. The dates of these meetings are available at Annex’ure C. During these meetings, the CUE delineated policy issues arising out of the concerns raised by the Hon’ble Supreme Court and deliberated on the same. The deliberations of the CUE were informed by inputs from the stakeholders. The Committee provided a detailed questionnaire (Questionnaire) to stakeholders prior to each consultation meeting. The Questionnaire is available at Annex’ure D.

The CUE adopted the following strategy for stakeholder consultation:

- Meetings with stakeholders: Stakeholders were given an opportunity to give oral submission on the issues mentioned in the Questionnaire through formal presentation which was followed by detailed question and answer session for addressing any further clarification.

- Written s’ubmission: In addition to consultation meetings, stakeholders were also given an opportunity to provide detailed written submission to the Questionnaire within the stipulated time-line.

The CUE consulted relevant stakeholders which included sectoral regulators, audit firms, professional institutes, industry associations and representatives from the industry. The list of stakeholders who engaged with the CUE is available at Annex’ure E.

The CUE gave sufficient time to all relevant stakeholders in providing their inputs to ensure a meaningful consultation process. Since this was a time consuming exercise, the CUE had to seek an extension of another three months from the Supreme Court for submission of the report. The Supreme Court granted the said extension vide order dated July 27, 2018. The extension order is available at Annexure F.

The COE greatly benefited from the thinking of prior committee reports includ-ing the following:

- Report on Corporate Audit and Governance, 2002 (committee headed by Naresh Chandra)

- ICAI, Study Group Report, 2003

- Standing Committee on Finance 21st Report on The Companies Bill, 2009, 2010

- ICAI, Expert Group Report, 2011

- Report of MCA ’s Expert Group on Issues Related to Audit Firms, 2017 (committee headed by Mr. Ashok Chawla)

In addition to these reports, the COE also examined global literature and identified the best practices in the auditing landscape in several jurisdictions like United States, United Kingdom and China.

The deliberations of the COE were also informed by the research conducted by its research secretariat, NIPFP.

1.2. Structure of report

The report is structured as follows: Chapter 2 provides a theoretical framework used by the COE to understand the role of auditors and the rationale for their regulation. It explains the role of auditors in resolving agency problems that are inherent in a corporate structure. The appointment of auditors raises new agency problems, creating various conflicts of interests. Moreover, concentration of market power is also another contemporary issue in the market for audit services. Accordingly, this Chapter argues that regulation of auditors is motivated by these two potential market failures – agency problems and market power – in the market for audit services. It concludes by identifying the broad categories of legal tools that could be used to regulate auditors. Based on this theoretical framework, Chapter 3 analyses the development of the audit profession and corresponding regulations across US, UK and China. In the backdrop of these global developments, this Chapter contextualises the development of Indian auditing market and chronologically explains the evolution of the current Indian legal framework governing auditors. Finally, Chapter 4 delineates the relevant policy issues arising out of the concerns raised by the Hon’ble Supreme Court, provides the opinion of the COE on each of these issues, and gives a rationale that pursuaded the COE to come to that particular opinion on each of the issues.

2.Role of auditors and their regulation

2.1. The basic problem

The efficiency of securities market depends on the availability of trustworthy financial information on the performance of companies. The more quickly new information is gathered, processed, verified and distributed among informed traders, the more efficient is the securities market.1

A fundamental hurdle in creating an efficient market for corporate securities stems from the agency problems inherent in the corporate structure itself. Such agency problems emanate from three types of information asymmetry. First, due to the separation of ownership and control in the corporate structure, the corporate managers may have more information about the company than its shareholder-owners. Second, the owners of the company who possess majority or controlling interest may have more information than the minority or non-controlling owners. Third, the company may have more information about itself than outside stakeholders with whom it contracts, such as creditors, employees and customers.2

In all the three instances, the agent enjoys informational advantage and may act opportunistically. This is the source of the agency problems. For instance, companies may be tempted to misinform investors in order to inflate the market price at Intial Public Offering (IPO) stage because those in control are selling the securities. This is problematic for investors seeking to rely on the corporate disclosures. Investor’s mistrust may prompt them to discount the value of the company’s shares or even to decline from investing.3 Such agency problems inherent in the corporate structure hamper development of an efficient market in corporate securities.

2.2. Auditors resolve agency problems

Corporate law provides various tools to mitigate these agency problems. One such tool is the trusteeship strategy. This requires a neutral decision-maker to exercise good faith best judgment in making a corporate decision.4 Auditors play this role of a neutral decision-maker. They provide an independent check on the work of the agent and information provided by the agent. This helps the principal maintain confidence and trust on the agent.5 This reliance placed on auditors to approve financial statements and certain corporate transactions is an example of the trusteeship strategy.6

Auditors are also referred to as ‘reputation intermediaries’. The principal trusts the auditor over her own agent as long as the auditor has a clean track record. And the auditor in turn pledges her hard earned reputation, built up over time, to vouch for the agent (the company or its managers). The assumption here is that an auditor being a repeat player in the capital markets has lesser incentive to deceive the principal than the agent. Theoretically, when an auditor has reputational capital whose value exceeds the expected profit from individual client relationship, she should be faithful to the principal.7

Auditors often play the critical role of ‘gatekeepers’. The term ‘gatekeeper’ literally means someone that controls access to an activity, in this case the capital markets. For example, a company seeking to access the public capital markets in most countries has to make use of the services of an auditor.8 This makes the integrity of auditors all the more important.

Even the legal liability regime on auditors has implications on capital markets. Auditors’ legal liability for an audit failure is an implicit insurance to outside investors. This insurance provided by the auditors enables entrepreneurs to raise capital from investors at lower costs.9

Although the concept of auditors orignated to resolve the agency problem within the corporate structure, in a modern economy their role extends beyond this scope. Various primary and subordinate legislation require accounts to be audited for use by stakeholders outside the company itself, like, tax authorities, regulators etc. For instance, under the Income Tax Act, 1961 certain persons carrying out business or profession are required to get their accounts audited. 10

Therefore, the integrity of auditors is critical for the functioning of various other institutions over and above the securities market.

2.3. Concerns about auditors

Although the primary role of auditors is to resolve agency problems, their appointment leads to a new set of agency problems. These new problems arise because although the auditors are appointed by the shareholders, in practice the management plays a critical role in recommending who should be appointed as auditors.11 The auditors therefore look to the CEOs and CFOs of the auditee company to facilitate continued engagement.12 Moreover, the auditee company may engage the audit firm for additional non-audit consulting services. The risk of losing fees from a long-term audit engagement and additional non-audit services could align the incentives of the auditors with those of the company’s management, creating new agency problems (commonly referred to as conflict of interest problems).13 These conflicts of interest could compromise the independence of auditors, rendering them incapable of resolving the original agency problems discussed earlier.

The provision of both audit and non-audit services raises further complications. Audit firms across jurisdictions often provide services as part of one common ‘network’. A ‘network’ is a larger structure which is aimed at cooperation and is clearly aimed at profit or cost sharing or shares common ownership, control or management, common quality-control policies and procedures, a common business strategy, the use of a common brand-name or a significant part of professional resources.14 Consequently, separate firms belonging to the same network could provide audit as well as non-audit services to the same audit client or its holding company or subsidiaries across different countries. It is possible that such non-audit services provided by one network firm to a company compromise the independence of another network firm which is providing audit services to the same company or its holding or subsidiary companies.

Once auditors’ independence is compromised, allowing auditors to act as gate-keepers could give rise to a potential moral hazard problem. The existence of a legal mandate to use auditors as gatekeepers may lull other market participants into a false sense of security, causing them to rely on the auditors and seek out less information on their own. Consequently, there may be an expectation gap between what the auditors can actually achieve and what stakeholders think they can achieve.15

Another serious concern is the lack of competition in the audit profession. 16 In a concentrated market dominated by a handful of market players, there are risks of implicit collusions. Moreover, in such a market, consumers of audit services may not have the ability to exercise choice effectively. Consequently, reputation risk itself may not be enough to check the behaviour of the dominant audit firms. This concern is further corroborated by instances of reputation-depleting behaviour by some audit firms.17

2.4. Rationale for regulation

Regulation of a market is not an end in itself. It addresses market failures.18 Similarly, regulation on the market for audit services should also be targeted to address potential market failures. As is evident from the discussion above, the market for audit services needs to be regulated to address two potential market failures: first, the agency problems emanating due to the inherent nature of the auditors’ role and the resulting moral hazard problems; second, market power

in the hands of few players which raises the possibility of abuse of dominance. These two potential market failures form the primary rationale for regulation of the market for audit services.

Legal regimes across jurisdictions have developed a range of tools to address such market failures. These legal tools could be broadly classified under six categories:19

1. Qualification and disqualification requirements: The law could lay down specific qualification requirements for acting as a statutory auditor. It could also disqualify persons from acting as auditor of a particular company on grounds of conflict of interest. Such a policy may extend to preventing auditors from providing certain non-audit services to audit clients or requiring mandatory rotation of auditors.

2. Disclosure obligations: The law could impose various disclosure obli-gations on auditors. Such norms could help reveal the conflict of interest that the auditors may face, the sources of funds they receive, and the methodology behind their recommendations.

3. Management of conflict: The law could incorporate rules to mitigate the conflict of interest faced by auditors. For instance, since the board within the company has greatest interest in a lax audit, the law could increase the role of shareholders in relation to audit decisions. Even within the board, it is the executive directors who have the greatest interest in lax audit. Given that shareholders face collective action problems, the law could increase the role of non-executive directors in relation to audit One example of this is the use of audit committees comprising independent non-executive directors.

4. Regulatory oversight: The law could also enhance the regulatory oversight on auditors, making them more accountable to the principal – the shareholders – and other stakeholders of financial statements of the auditee company.

5. Auditors’ power: The law could increase the power that auditors wield against the audited company, thereby making audit decisions more independent. For instance, the law could restrict the maximum fees earned by an auditor from an audit client to ensure that no one audit client is of such substantial material importance to the auditor so as to bias its independence.

6. Liability risk: The law could increase the liability risk of auditors, over and above their reputation risk. This could be achieved by allowing parties who rely on the audited accounts and reports to impose civil liability (damages) on negligent auditors. For instance, the law could increase the litigation risk that auditors could face for negligence. Similarly, criminal liability could be imposed on auditors for false statements in audit reports.

The next chapter applies this theoretical framework to analyse the evolution of the laws and regulations on the market for audit services across some major jurisdictions as well as in India.

3.Global developments and best practices

The early origins of the audit profession can be traced back to medieval Europe.1 Since then the profession evolved organically out of the competitive dynamics of free markets. But it was the development of limited liability companies in nineteenth century England and America that created a demand for professional accountants and auditors. Prompted by insolvencies and scandals arising out of such limited liability companies,2 especially railway companies, the English Companies Act, 1845 for the first time required semi-annual audits of accounts of certain companies by an audit committee composed of shareholders. Although this audit requirement was removed subsequently, the English Companies Act, 1900 reintroduced compulsory audit for limited liability companies.3

The first English professional societies for accountants were set up in 1870. These professional societies established their brand-names by restricting entry of accountants through examinations, establishing standards of conduct, and by adopting the title of ‘chartered accountants’ for their members. The 1880 Charter of Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales listed the accountants’ functions as liquidators, receivers, trustees and auditors, in that order. By 1900, virtually all traded UK companies were audited by professional chartered accountants.4

The growth of bankruptcy and liquidation work for accountants that occured

in England during the nineteenth century did not occur in U.S.5 As a result, professional societies were established in U.S. later and were influenced by British accounting firms.6 For instance, the American Association of Public Accountants (AAPA) – the predecessor of the present American Institute of Certified Public Accountant (AICPA) – was set up in 1887, and the accreditation system began in 1896. By 1920s, most companies listed on New York Stock Exchange were being audited by professional auditors.7

It is evident from the above vignettes that the modern audit profession origi-nally evolved organically out of the competitive dynamics of free markets. The early professionals self-regulated themselves to differentiate themselves from lay accountants and to signal their quality and credibility to potential clients.8 How-ever, subsequent events prompted increased levels of state interventions, which have largely shaped the current regulatory architecture as well as regulations on the modern audit profession across major economies.

3.1. United States of America

Following the stock market crash of 1929, the Securities and Exchange Act, 1933 for the first time made it mandatory for U.S. publicly listed companies to have independent outside auditors certify the fairness of their financial reports.9 Many of the audits that immediately followed were not conducted independently and simply relied on information supplied by the management.10 This prompted

the AICPA to require auditors to inspect inventories and confirm receivables themselves rather than depend on information from their audit clients.11 Even the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), which initially administered the Securities and Exchange Act, specifically required ‘independent auditors’ not to have any direct or indirect interest in the client.12 Thus, from early on auditor independence became a critical issue in U.S.

In 1939, the SEC set up a private standard setting body – the Commission on Accounting Procedures, which subsequently became the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) – to establish accounting standards. However, SEC retained the authority to supercede any accounting standard adopted by FASB, if necessary. The accounting profession was left to regulate itself through its professional body, the AICPA. However, state authorities like SEC retained authority to set and enforce standards and discipline those practicing before it.13 As per Rule 102(e), the SEC can censure an auditor as well as audit firm or deny it, temporarily or permanently, the privilege of appearing or practicing before it for lack of qualification or unethical conduct.14

The SEC has always been concerned about the impact of non-audit services on auditor independence. In 1978, it promulgated the Accounting Series Release No. 250 requiring disclosure of non-audit services performed by independent auditors in terms of their percentage relationship to audit fees. It also issued Accounting Series Release No. 264 regarding the scope of non-audit services to enable companies and their auditors to determine whether any proposed management advisory service engagement should be offered or accepted. At that time, the SEC was not keen to prohibit any particular management advisory service. Instead, it expected the accountants to serve as front line guardians of their professional independence. 15

This self-regulation model had to be reviewed after the WorldCom and Enron scandals in early 2000s. To rebuild investor confidence in the public markets, the Congress enacted the Sarbanes Oxley Act, 2002. It marked the transition from a self-regulatory model to an independent oversight model of auditor supervision. It established PCAOB, a full-time, independent board to conduct

inspections of audits. The PCAOB has five members, who are appointed to staggered five-year terms by the SEC, after consultation with the Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, and the Secretary of the Treasury. The PCAOB establishes or adopts standards for auditing, quality control, ethics and independence, taking into account public comments, and subsequently conducts economic analysis of such changes. The PCAOB is further vested with investigation and disciplinary powers. It can also revoke registration and impose monetary penalties on auditors.16

The Sarbanes Oxley Act, 2002 makes it unlawful for any audit firm, that is not registered with PCAOB, to prepare or issue, or to participate in the preparation or issuance of, any audit report with respect to any issuer, broker, or dealer.17 The law imposes a legal obligation on PCAOB to conduct a continuing program of inspections to assess the degree of compliance of each registered audit firm with all applicable laws and professional standards in connection with its performance of audits, issuance of audit reports, and related matters involving issuers.18 Annual inspections are conducted for firms which provide audit reports for more than 100 clients and once every three years for firms providing audit reports for 100 or fewer issuers.19 The inspection results are published in the public domain if the audit deficiencies are not addressed by auditors within twelve months.20 This acts as a deterrent for audit firms because of the potential reputational damage for them.

The PCAOB also inspects those registered public accounting firms located in foreign jurisdictions that prepares or furnishes an audit report with respect to any issuer. Such inspection is carried out to assess those firms compliance with the Sarbanes Oxley Act, 2002, the rules of the PCAOB, and the SEC.21

The Sarbanes Oxley Act, 2002 also strengthened auditor independence by prohibiting auditors from providing certain non-audit services to their publicly traded audit clients.22 It also strengthened the role of the audit committee in public companies by requiring them to pre-approve all audit and non-audit services entrusted by the company to the auditor.23

The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, 2010 fur-ther empowered the PCAOB with expanded oversight of brokers and dealers registered with SEC. PCAOB now has registration, inspection, standard-setting, and disciplinary authority over the auditors of broker-dealers. When broker-dealers file their annual reports with the SEC, they are required to include their financial statements and supporting schedules, along with audit reports thereon prepared by PCAOB-registered public accounting firms. Broker-dealers also are required to file compliance or exemption reports, along with examination or review reports that are prepared by the same firms that prepared the audit reports. The audits, examinations, and reviews are required to be performed in accordance with PCAOB standards.24

The regulation of public accounting firms i.e., auditors of listed entities is done both by SEC and PCAOB. However, SEC is the oversight authority of PCAOB.25 SEC has the authority to take action against an auditor for professional misconduct or violating securities laws.26 As explained in Figure 3.1, the investigation is carried out by the Enforcement Division of SEC in-dependent from the Office of Administrative Law Judge which is responsible for disciplinary proceedings and issuing sanctions. Since investigations can be carried out by both SEC and PCAOB, such investigations are duly co-ordinated. Further, PCAOB can refer an ongoing investigation to SEC.27 The regulatory structure provides a clear separation of functions like inspection, investigation and adjudication, which are conducted by different divisions of PCAOB.28

3.2. United Kingdom

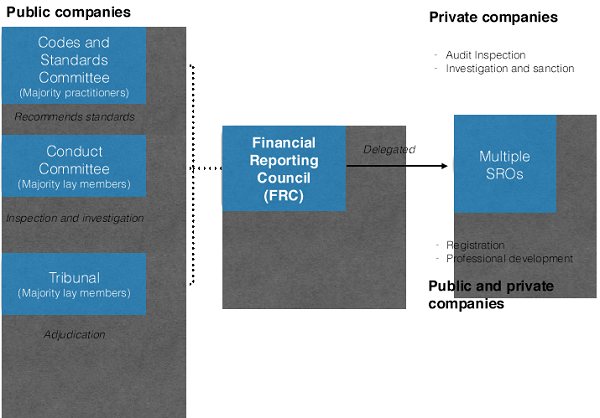

In 2002, immediately after the Enron debacle, the UK government undertook a review of the regulatory regime for auditors and accountants and the chal-lenges associated with the SRO regime. The principle recommendation of the review exercise was to enhance the monitoring of the listed entities through an independent audit regulator.29 While FRC existed at that time, but this review exercise lead to its integration. In April 2004, FRC became the UK’s unified independent regulator for corporate reporting and governance.30 Currently, FRC is the competent authority responsible for the public oversight of statutory auditors.31 It also assumed the responsibility for issuing accounting standards and dealing with their enforcement.

UK follows a two-tier structure which consists of an independent audit regulator and multiple front-line SROs. The critical regulatory activities concerning the auditors of public interest entities are vested with FRC, whereas some tasks have been delegated to the multiple SROs – Recognised Supervisory Bodies (RSBs) and Recognised Qualification Bodies (RQBs).32 RSBs supervise certain aspects of auditors, whereas RQBs award appropriate audit qualification. These SROs are recognised under the Companies Act, 2006 subject to certain eligibility conditions.33 These are not statutory bodies and can be de-recognised for breaching obligations.

The FRC has currently appointed four RSBs and five RQBs. Some of these are – Association of Chartered Certified Accountants, Chartered Accountants Ireland, Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales, Institute of Chartered Accountants of Scotland. Each individual RSB is responsible for maintaining its own standards that are overlooked by the FRC. The FRC can also impose financial penalty on RSBs for breaching its obligations and such enforcement measure is published in the public domain.34

The FRC functions through the help of various committees. For instance, it sets the accounting standards through the Code and Standards Committee which takes into account views of stakeholders. Since setting of accounting standards requires expertise, this committee consists of majority of practitioners. On the other hand, the Conduct Committee of FRC, which conducts inspection of audits and regulation of SROs, has a majority of lay members. Further, to ensure objectivity in its function, the Conduct Committee excludes current practising auditors and has no officers of the SROs it regulates.35

As Figure 3.2 shows, if the auditors dispute the findings of the investigation, then an independent disciplinary Tribunal is appointed.36 The Tribunal consists of majority of non-accountants and never has any employee from other division involved in investigation or prosecution. Therefore, the current structure of FRC separates the function of investigation from adjudication to ensure fairness and objectivity. In sum, all the committees in FRC have been composed in a manner to ensure optimum balance between independence and expertise.

The Companies Act, 2006 prohibits a person from acting as an auditor unless such person satisfies the independence requirements in the statute.37 Violation of

the independence requirements by an auditor could invite criminal sanctions.38 The APB Ethical Standard 5 places the task of identifying and managing threats to independence arising out of non-audit work primarily on auditors, but certain types of non-audit services are identified as particularly dangerous and should not be undertaken. These include non-audit services like internal audit, IT design of accounting systems, valuation, acturial services, certain tax services.39

The Companies Act, 2006 also empowers the Secretary of State to issue disclosure regulations to address potential conflict of interest arising out of non-audit services. The Secretary of State has issued regulations for disclosure of terms on which a company’s auditor is appointed, remunerated or performs his duties; the nature of any services provided for a company by the company’s auditor or by his associates; the amount of any remuneration received or receivable by a

Box 1: Sanction on Big Four

In 2017, an independent review was undertaken by a panel chaired by former Justice Sir Christopher Clarke.a The review while discussing sanctions, stated that smaller fines allowed the Big 4 to continue to conduct business by looking at sanctions as the ‘cost of doing business’. While larger fines would discourage smaller firms from conducting larger scale audits and can cause further segregation of the market. The report concluded by suggesting the Big 4 be treated as a separate category when dealing with sanctions. Justice Clarke further recommended an increase in fines to GBP 10 million or more for poor audit work from a Big 4 accounting firm. The FRC accepted the recommendations from the review. It also agreed to make greater use of non-financial penalties like excluding dishonest auditors from the accounting profession for atleast 10 years.

_________________________

a Clarke, Chambers, and Long, Independent Review of the Financial Reporting Council’s Enforcement Procedures Sanctions.

The civil liability of an auditor towards the audited entity for a negligent audit is well-established under English law. However, civil liability towards non-client claimants is limited. While in other jurisdictions there has been a move from joint and several liability for auditors to a proportionate liability regime, the Companies Act, 2006 provides for an alternative solution by recognising liability limitation agreements between a client company and its auditor.41

Additionally, the FRC has introduced its Audit Enforcement Procedure (‘AEP’), which has only been in operation since June 2016. The Sanctions Policy (Audit Enforcement Procedure) supports the AEP. The AEP is concerned with relevant breaches by Statutory Auditors and Statutory Audit Firms. For instance, it would cover a failure to comply with the standards of professional competence, due care and professional scepticism.42 As shown in Box 1, the effectiveness of this sanctioning regime on the Big 4 audit firms is questionable.

Concentration in the market for audit services has emerged as a serious concern for contemporary British policymakers. Following the collapse of the construc-tion company Carillion earlier in 2018, the Work and Pensions Committee reviewed the regulations on the audit profession in UK and expressed serious concerns. The Committee noted that in 2016, the Big Four audited 99% of the FTSE 100 and 97% of the FTSE 250 companies.43 In this oligopolistic market, Carillion through its employment of Deloitte (internal auditor), KPMG (external auditor), EY (financial advisor) and PWC (advisor on government contracts) created a situation wherein FRC was forced to appoint the least conflicted out of those firms to review the company’s audits. This allowed PwC to dictate its price thereby turning the oligopoly into a monopoly.

Accordingly, the Committee concluded that waiting for a more competitive market that promotes quality and trust in audits has failed. Instead, it recom-mended referring the statutory audit market to the UK anti-trust regulator, which should consider both breaking up the Big Four into more audit firms, and detaching audit arms from those providing other professional services.44 In October, 2018, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) issued a consultation document on the market study it plans to carry out to consider whether the market for the provision of statutory audit is working properly. This study aims to focus on three main issues i.e., improvement of incentives, separation of audit and non-audit services and reducing barrier to entry and expansion of non-big four audit firms.45

3.3. China

In 1949, the People Republic of China was founded, which lead the accountancy profession towards a development course based on the model of socialism. It was only in 1979, when economic reforms started, the existing structure of accountancy profession was revisited. In 1979, the Government promulgated laws on Chinese-foreign equity joint venture which required foreign entities both wholly owned and joint-venture to have their annual financial statements audited by Certified Public Accountants (CPAs). This lead to the growth of new accounting firms which provided services to foreign owned enterprises, because state owned enterprises was not required to be audited.46

In 1981, the Government allowed the entry of accounting firms which were part of the global network. The Big six firms opened their representatives offices in mainland China for liaison and consulting purposes because rules did not permit audit functions.47 In 1985, the Government approved the new accounting regulations for the Chinese and foreign joint ventures which took the accounting profession closer towards the global norms.

In 1988, the Chinese Institute of Certified Public Accountants (CICPA) was established under the supervision of the Ministry of Finance as a SRO.48 In 1992, the Ministry of Finance granted special approval to the Big six firms to form joint venture with the state controlled local accounting firms. This allowed these firms to enter into the domain of auditing, advisory, tax and other professional services in China.49

However, the joint venture structure did not turn out to be much successful for the Big six firms due to interference of the local partner. Therefore, they pushed for allowing the network membership route. In 1996, the Ministry of Finance allowed the international firms to identify members firms in China subject to certain conditions.50

The securities market had a significant impact on the accounting profession in China. The Chinese enterprises raised funds outside mainland China for which they were required to get financial statements prepared in accordance with the international accounting standards.51 In 2001, the Chinese Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) issued a regulation which mandated companies seeking listing of shares to get their financial statements audited by international accounting firms.52 The foreign invested enterprises also fuelled growth in the non-audit services which were rendered mostly by the member firms.53

The companies listed on different stock exchanges (Shanghai Stock Exchange, Shenzhen Stock Exchange, Hong Kong Stock Exchange) were required to follow different accounting standards and hence, there was no uniformity. Several developments took place in bringing the Chinese accounting standards at par with the international norms. In 2009, the Ministry of Finance converged the standards with the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS).54

Presently, the accounting profession in China is regulated by three authorities i.e., Ministry of Finance, CSRC and CICPA. Firms are licensed by the Ministry of Finance. The firms providing securities related services are jointly licensed by the Ministry of Finance and CSRC. The Ministry of Finance and CSRC also have powers to investigate and take disciplinary actions against auditors of listed entities. CICPA as a professional body, has oversight authority over the firms and the individual CPAs. The accounting standards are set by the Ministry of Finance; whereas CICPA sets the auditing standards but issued by the Ministry of Finance.55

The Law of the People Rep’ublic of China on Certified P’ublic Acco’untants, 1993 states that while CICPA is the national organisation of CPAs, there are local CPA institutes which represent CPAs operating in different provinces.56 Under this law, every CPA is required to join a local CPA institute in respective provinces. These local institutes are responsible for conducting annual examina-tion on professional qualification and annual practice inspection of CPAs.57 The local CPA institutes can revoke the registration of CPAs on grounds of profes-sional misconduct.58 The CICPA can take the following disciplinary measures i.e., reprimand, criticism by circulating notice and public condemnation for non-compliance by its members.59 The finance department of the government at the provincial level or above can issue disciplinary warnings to individual CPA or firm of CPAs for violations and award punishments like, suspending their operations or impose fines.60

Year Developments

2002 High Level Committee on Corporate Audit and Governance

2003 ICAI Study Group Report

2007 Constitution of Quality Review Board (QRB), changes in disciplinary proceedings

2009 Satyam financial fraud CII Task Force on Corporate Governance

2010 Parliamentary Standing Committee on Finance on Companies Bill, 2009

2011 ICAI Study Group Report on operations of MAF

2013 Notification of Companies Act, 2013

2016 Company Law Committee recommends constitution of NFRA

2017 Report of MCA’s Expert Group on Audit Firms

Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) passes order against 2018 Price Waterhouse (PW)

Supreme Court judgment in S.Sukumar v The Secretary, ICAI Cabinet approval on setting up NFRA

Table 3.1.: Important milestones in Indian auditing landscape

3.4. Indian developments

Although the collapse of Enron in 2001 and the demise of Aurther Andersen in 2002 were watershed moments for corporate governance globally, the initial stimulus of corporate governance reforms in India was generated by the Asian financial crisis in 1997-98. Two subsequent events – the Satyam scam and the enactment of the Companies Act, 2013 – further shaped the Indian corporate governance regime. Accordingly, this section will review the development of the Indian regulations on auditors and audit firms across three phases – from the Enron fallout in 2002 to the Satyam scam in 2009, from Satyam scam to the enactment of the Companies Act, 2013 and post the enactment of Companies Act, 2013 till now. Table 3.1 highlights the most critical developments over this period.

3.4.1. Enron fallout: 2002-2009

In the midst of the global churn in corporate governance reforms, the Indian government in 2002 appointed a High Level Committee on Corporate Audit and Governance chaired by Mr. Naresh Chandra to examine various corporate governance issues. This committee undertook a comprehensive examination of various aspects of corporate governance that arose in the context of the Enron failure. Closely on the footsteps of the Report on Corporate Audit and Governance, the ICAI in 2003 issued a Study Group Report which discussed the competition issues in the context of Indian audit firms and firms being members of the international network. In parallel, the Report of the Expert Committee on Company Law headed by Mr. J.J.Irani while suggesting reforms to the company law in 2005, made relevant recommendations pertaining to conflict of interest and liabilities on auditors.

Three major themes of policy reforms emerged from these developments: first, the need to move from the self-regulation model to an independent oversight model for the audit profession like the PCAOB; second, reducing conflict of interest arising out of non-audit services provided by statutory auditors; and third, the competition faced by Indian audit firms from their international counterparts.

First, on the issue of setting up a public oversight body, the Report on Corporate Audit and Governance examined the PCAOB structure. However, it accepted the arguments of ICAI that there was no need for a new regulator and, instead, the existing mechanism needs to be strengthened.61 As a middle path, it recommended setting up an independent QRB under the Chartered Accountants Act, 1949 to refine the quality of attestation of audits.62

Second, regarding conflict of interest arising out of non-audit services, both Report on Corporate Audit and Governance and Report of the Expert Committee on Company Law stated that there should not be a blanket ban on rendering non-audit services because it could make auditors more dependent on their audit clients for revenue. Instead, prohibition on certain types of non-audit services was recommended, as was the position under section 201 of Sarbanes Oxley Act, 2000. The Report on Corporate Audit and Governance was of the view that audit firms having affiliated and associated entities engaged in non-audit services like consultancy were necessary for better growth and knowledge development. To mitigate the potential conflict of interest issues arising out of such non-audit engagements, it recommended that no more than 25% of the revenues of the consolidated entity should come from a single corporate client with whom there is also an audit engagement.63On the other hand, the Report of the Expert Committee on Company Law highlighted the importance of the liabilities and duties of auditors in mitigating conflict of interest concerns and recommended that these should be put in the law itself instead of rules.64

Third, the competition faced by Indian audit firms from their international counterparts was a critical concern for policymakers in this phase. The Report on Corporate Audit and Governance noted that out of approximately 43,000 Indian audit firms, only 0.5% of the firms had more than 10 partners and more than three-fourth of the firms were self-proprietorship concerns. Given such chronically small size, the report was apprehensive that the Indian firms will not be able to compete with international firms in the lucrative consultancy and non-statutory work market. Therefore it was of the view that policymakers should facilitate consolidation of smaller Indian audit firms. It also recommended introduction of limited liability partnership firms to attract more talent to join the profession.65 The Study Group Report by ICAI also discussed the competition issues between Indian audit firms and firms part of the international network. It concluded that networking between Indian firms and international firms should be promoted.

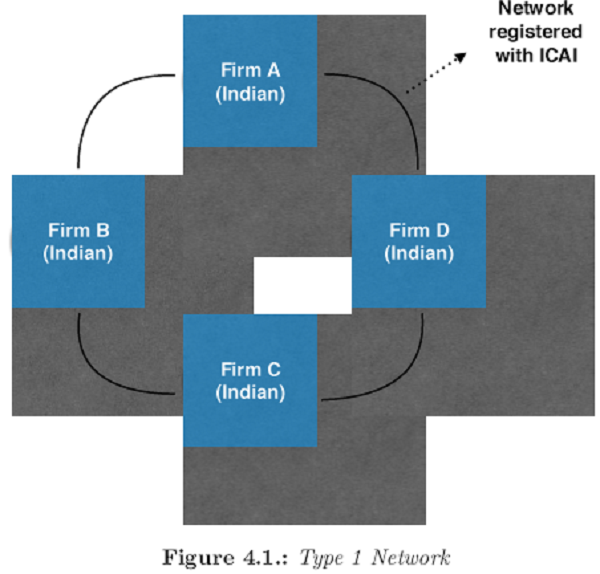

The policy deliberations in this phase led to four critical legal reforms from 2005 to 2008. First, the ICAI acted upon the recommendations of its Study Group Report and issued the rules of networking in 2005 allowing Indian firms registered with ICAI to network with MAFs subject to prescribed disclosures given in the rules.66

Second, the Chartered Accountants Act, 1949 was amended based on the recommendations of the High Level Committee on Corporate Audit and Governance (Naresh Chandra committee). The newly inserted section 28A of the Chartered Accountants Act, 1949 provided for the setting up of a QRB. Broadly inspired by the PCAOB, the QRB is supposed to review the quality of services provided by the members of ICAI.67 The QRB consists of 11 members. The chairperson and five members are nominated by the Central Government and the rest five are nominated by the council of ICAI.

Third, the 2006 amendment to the Chartered Accountants Act, 1949 also stream-lined the disciplinary mechanism within ICAI. Once a complaint is filed before the Director of Discipline (DD), it is required to formulate a prima facie opinion and then place it before the Board of Discipline (BOD) or Disciplinary Com-mittee (DC) depending on the nature of violation. Earlier, the final decision on punishment was taken by the council of ICAI, which is the highest decision making authority. Since the council consists of many members, the meetings were not frequently held which delayed the decision making process. After the amendment, the power to revoke the membership or impose monetary penalty has been vested with the BOD and DC.68

Fourth, the Limited Liability Partnership, 2008 was enacted. However, it was only in 2012 that the Chartered Accountants Act, 1949 was amended to allow chartered accountants to incorporate as LLPs, as was originally suggested by the Report on Corporate Audit and Governance.

Evidently, the transformation of the regulatory architecture of the Indian audit profession from a self-regulation model to an independent oversight model began in this phase with the establishment of the QRB. In parallel, reforms were also initiated to facilitate the development of Indian audit firms by formally providing a framework for international networking as well as enabling them to structure as LLPs.

3.4.2. Post Satyam: 2009-2013

The unravelling of the Satyam scandal from December 16, 2008 started ex-posing shortcomings in the extant Indian corporate governance regime. These developments prompted multiple studies of the corporate governance regime in India, that shaped the second phase of policy reforms in this space.

In February 2009, the CII constituted a task force on corporate governance under the chairmanship of Mr. Naresh Chandra. This task force made various recommendations to address the conflict of interests faced by auditors and audit firms. These recommendations fed into the Corporate Governance Voluntary Guidelines, 2009 issued by the MCA. Since the guidelines were voluntary in na-ture, they lacked enforcement capacity. Consequently, the Standing Committee on Finance reviewing the Companies Bill, 2009 recommended incorporating the substantive contents of the Corporate Governance Voluntary Guidelines, 2009 into the bill. The Standing Comittee on Finance also considered suggestions given by various stakeholders for setting up an independent oversight body for auditors and to bring auditing standards within the jurisdiction of company law. In January 2009, the ICAI also set up an expert group to study the functioning of audit firms in India and the different kinds of networks between Indian firms and international audit entities. However, in the absence of sufficient informa-tion, no conclusive position was arrived at. The Expert Group Report issued in 2011 recommended the council of ICAI to further examine the matter.69

Evidently, two major themes of policy reforms emerged during this phase, which ultimately influenced the Companies Act, 2013 : first, the need for an independent oversight body for auditors; second, the various legal strategies for addressing auditors’ conflict of interest.

First, section 210A of the Companies Act, 1956 provided for the National Advisory Committee on Accounting Standards (NACAS) which had the mandate to formulate accounting standards for adoption by companies. However, the power of setting auditing standards remained vested with ICAI. The Standing Committee proposed to change this by enhancing the role of NACAS to making recommendations on accounting and auditing standards.70 It was also proposed that the name of NACAS be changed to National Advisory Committee on Accounting and Auditing Standards (NACAAS). The standing committee further recommended that NACAAS should also act as as a quasi regulator to monitor the quality of audit undertaken across the corporate sector.71

Second, on the issue of conflict of interest, Corporate Governance Voluntary Guidelines 2009 recommended mandatory disclosure of network agreements and pecuniary interests between audit firms and their respective non-audit network entities. It also recommended a cap on fees earned by an audit firm and all its associated entities from a single audit client. It further suggested that auditors’ liability should not be limited to the signing partner but must be extended to the audit firm.72 The Corporate Governance Voluntary Guidelines, 2009 further recommended the presence of a majority of independent directors in the audit committee and need for certificate of independence by auditors to ensure an arms’ length relationship with the client. It also required the auditor to specifically state the impact of non-receipt of certain information from the management. On its part, the Standing Committee not only endorsed the negative list of non-audit services incorporated in the draft bill but also recommended expanding its scope to subsidiary companies of the audit client.73

Evidently, in this phase, the Satyam debacle prompted rethinking of the regula-tory architecture beyond the QRB under the aegis of ICAI, towards a PCAOB like regulatory body which will monitor the quality of audit undertaken by auditors and audit firms in India. Even the strategies that were proposed for addressing conflict of interest concerns during this phase were more sophisti-cated. For instance, a general consensus seemed to have emerged that conflict of interest could arise at the network level and not merely at the firm level. Further, if non-audit services are provided by the statutory auditors to the parent, subsidiary or any associate entity of the audited company, that could also create conflict of interest. These considerations that emerged during the policy deliberations at this stage, went on to inform the reforms in the next phase.

3.4.3. New Companies Act: 2013 – 2018

Three relevant developments stand out in this phase. The first was the enactment of the Companies Act, 2013. Second, the manifestation of the Satyam episode in this phase revealed critical limitations and ambiguities in the Chartered Accountants Act, 1949. Although some of them have been addressed in the Companies Act, 2013, certain other issues are still contested. Third, this phase

has also seen an active initiative being undertaken by sectoral regulators like Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and SEBI in improving professional accountability of auditors undertaking activities in their respective sectors. These three issues are not necessarily mutually exclusive and therefore, it is relevant to analyse them in detail to appreciate their implications.

First, the Companies Act, 2013 finally provided for establishment of an inde-pendent statutory regulator – the NFRA – for matters relating to accounting and auditing standards.74 In line with the powers vested with PCAOB under section 101 of Sarbanes Oxley Act, 2002, the Companies Act, 2013 empowered NFRA to:75

1. give recommendations to the Central Government on laying down account-ing and auditing standards;

2. monitor and enforce compliance of standards and oversee the quality of service of the profession and give recommendations;

3. investigate professional misconduct committed by the members of ICAI for prescribed class of body corporate or persons; and

4. issue order imposing monetary penalty as well as debarring an individ-ual member or firm registered with ICAI for 6 months to 10 years, for professional or any other misconduct.

Even after being accorded statutory status, the debate on the need for NFRA continued. In 2016, this issue was considered by the Companies Law Committee, which was constituted to suggest amendments to the Companies Act, 2013. At that time, ICAI had raised objections on the constitution of NFRA. The Companies Law Committee concluded that auditors play a critical role and due to serious lapses in the past, an independent body to oversee the profession was required. It also observed that major economies in the world have already established such regulatory bodies. The Companies Law Committee accordingly recommended that NFRA should be established at the earliest.76 Evidently, there is now wide consensus among experts and policymakers about the merit of an independent statutory regulator like NFRA for the Indian audit profession.

Moreover, adoption of NFRA will be in tune with the internationally accepted global best practices in this regard.

The continued debate about the need for NFRA has delayed the implementation of this critical reform. Consequently, although the Companies Act, 2013 was notified in August 2013, the section establishing NFRA was notified only on March 21, 2018 along with the NFRA Chairperson and Members Appointment Rules, 2018.77 Currently, the rules on the functioning of NFRA are in draft stage. Once these rules come into effect, NFRA will become fully operational.

The Companies Act, 2013 also addressed the issue of conflict of interest. Inspired by section 201 of the Sarbanes Oxley Act, 2002, section 144 of the Companies Act, 2013 explicitly prohibits provision of eight types of non-audit services by the statutory auditor. Based on the suggestions of previous committees, the prohibition has been extended to the subsidiary or holding company of the audit client. Further, the restriction is also applicable to associate entities of such auditor.78 The law has also introduced audit firm liability for violations under the Companies Act, 2013.79 Evidently, India has now adopted the current global best practice in this regard too.

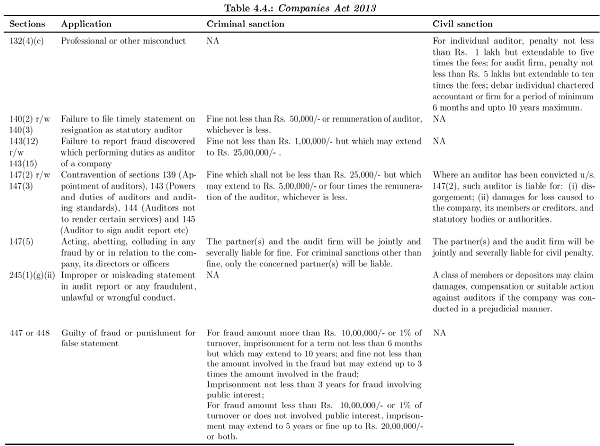

In spite of such major strides in legislative reforms through Companies Act, 2013, subsequent events in this phase following the unravelling of the Satyam scandal have led to the second development revealing some limitations and ambiguities in the Chartered Accountants Act, 1949. As is evident from Box 2, the most critical limitation under Chartered Accountants Act, 1949 has been the liability regime on auditors. While monetary liability on an individual auditor is capped at Rs. 5 lakhs, there is no monetary liability on audit firms at all.80

However, this loophole will soon be plugged once NFRA becomes fully opera-tional. In case of any professional or other misconduct, NFRA has statutory powers under Companies Act, 2013 to impose monetary penalty up to five times the fees received by an individual auditor or up to ten times of the fees received by an auditor firm. In addition, such individual auditor or the firm could also be debarred from practising for up to ten years by NFRA.81 Consequently, the limitations in the liability regime under the Chartered Accountants Act, 1949

Box 2: The Satyam case

After the fraud at Satyam Computers Services Ltd. (‘Satyam’) came to light, the PwC partners involved in the incident were stripped of their ICAI membership and were even imprisoned. Even SEBI has passed a disgorgement order of Rs. 3,09,01,664/- against one of the member firms of PwC network as well as the individual audit partners involved under section 11B of the Securities and Exchange Board of India Act.a However, disgorgement can only take away illegal gains made by the auditor but cannot indemnify investors for a fraudulent or failed audit. Consequently, investors in Satyam’s shares in India were never indemnified for the fraud played on them.

In contrast, since Satyam was listed on New York Stock Exchange, a civil money penalty of $7.5 million was imposed on PwC by the SEC and PCAOB in 2011.b Additionally, the investors in Satyam’s American Depository Receipts (ADRs) filed a Consolidated Class Action Complaint under Sections 10(b) and 20(a) of the Securities Exchange Act, 1934 against Satyam as well as the auditor PwC firms. The matter finally reached a settlement with Satyam and PwC agreeing to pay the ADR investors $25.5 million.c

________________________

a. Securities and Exchange Board of India, In respect of Price WaterHouse Co and Others, p. 107.

b. Securities and Exchange Commission, In the Matter of Lovelock & Lewes.

c. United States District Court, In re: Satyam Computer Services Ltd.

could be adequately addressed by NFRA under the Companies Act, 2013.

The Satyam episode also highlighted the role played by international networks, over and above audit firms. Questions were raised about the legality of op-erations of such networks under the Chartered Acco’untants Act, 1949. There were concerns that restrictive conditions imposed by foreign investors tilt in favour of larger audit firms affiliated with these international networks. In this backdrop, the MCA constituted an expert group chaired by Mr. Ashok Chawla in 2016 to look into the regulatory aspects of audit firms. In 2017, the expert group submitted its report which explicitly clarified that the so called MAFs are Indian audit firms with international affiliation but they are controlled and managed by Indian nationals. Further, the report stated that these Indian nationals are members of ICAI and all such network firms have firm registration number issued by ICAI.82

The Report of MCA ’s Expert Gro’up on Iss’ues Related to A’udit Firms observed that ‘merely being part of a network and sharing global costs does not make them MAFs as they are neither owned or controlled by the global parent’. Therefore,

it came to the conclusion that ‘it would not be appropriate to consider the so called MAFs as multinational entities’ since there is no foreign control either through ownership or management and the network partners are run, controlled and managed by Indian nationals.83 In spite of the clarifications in the Report of MCA ’s Expert Group on Issues Related to Audit Firms, questions about the legality of various operations of these networks still exist. This CUE seeks to clarify these issues in detail in the next chapter.

The third major development in this phase has been the initiatives taken by sectoral regulators like RBI and SEBI in improving professional accountability of auditors undertaking activities in their respective sectors. Towards the end of 2017, SEBI issued the Report of the Committee on Corporate Governance where it recommended that there should be adequate disclosure of total fee (audit and non-audit services) earned by the auditor and all entities on the network firms/network entity of which the auditor is a part of.84

In early 2018, SEBI penalised PW for its involvement in the Satyam case by prohibiting PW and all its network firms to undertake statutory audit of any listed entity for a period of two years.85 Thereafter, in the matter of operation of audit firms who are members of the international network, the Supreme Court delivered its judgment and instructed the Government to constitute a CUE to look into regulatory aspects of such audit firms.86

In July 2018, SEBI issued a consultation paper seeking comments on its proposal to amend several regulations related to the role of fiduciary under the securities laws. The proposed definition of fiduciary includes Chartered Accountant (CA) as well as statutory auditor.87 In parallel with SEBI, RBI has also racheted up

its supervision on auditors in the banking sector.88 In June 2018, RBI issued a graded enforcement action framework to enable appropriate action by the RBI in respect of the banks’s statutory auditors for any lapses observed in conducting a bank’s statutory audit.89

In 2018, MCA issued rules on appointment of members of NFRA.90. The year 2018 also witnessed the resignation of several statutory auditors of listed entities over a short period of time. MCA has already ordered investigation to ascertain the reasons behind these resignations.91

Evidently, in this third phase, India has experienced legislative reforms which have upgraded the regulatory structure on auditors and audit firms in tune with the current international best practice. The limitation on the auditor liability regime under the Chartered Accountants Act, 1949 has now been resolved by establishing and empowering NFRA under the new Companies Act, 2013. In parallel, this phase has also seen positive regulatory initiatives across sectors to provide an additional layer of transparency and accountability in the Indian audit profession over and above the statutory scheme under the Companies Act, 2013 and the Chartered Accountants Act, 1949. ilowever, as noted by this CUE, doubts persist as to the application of Chartered Accountants Act, 1949 on networks of audit firms, which will be analysed in the next chapter.

4.Issues, findings and

recommendations

4.1. Whether India has an appropriate mechanism for oversight of the audit profession?