CCI releases key findings and observations on Market Study on Pharmaceuticals Sector in India

The Competition Commission of India (CCI) has released here today a report titled ‘Market Study on the Pharmaceutical Sector in India: Key Findings and Observations’ (`the study’).

The report may be accessed at:

http://cci.gov.in/sites/default/files/whats_newdocument/Market-Study-on-the–Pharmaceutical–Sector-in-India.pdf

With the overarching objective of understanding the factors that influence price competition in the pharmaceutical sector, the study focused on the specific realms of pharmaceutical distribution and the role of trade associations therein, trade margins, online pharmacies and the prevalence of branded generic drugs in India and its implications for competition. Since the pharmaceutical sector is a regulated sector, the study also attempted to explore the areas of interface between regulation and competition with a view to ascertain the CCI’s advocacy priorities.

The report summarises the main findings and the CCI’s observations based on the study. It is expected that the insights gained from the market study will inform and contribute significantly to the design of the pharma market in India to help attain the objective of affordable medicines for all.

*****

MARKET STUDY ON THE PHARMACEUTICAL

SECTOR IN INDIA

Key Findings and Observations

18-11-2021

Competition Commission of India

10th Floor, Office Block – 1, Kidwai Nagar (East),

New Delhi – 110023, India

Disclaimer

This market study report on the pharmaceutical sector in India and the information contained herein is for general purposes only and is based on broad trends and views that have emerged in the study. This report is not intended to be exhaustive, and does not provide a complete summary of any issue(s) pertaining to the pharmaceutical sector in India and is not a legal document, which may be used for the purposes of any proceedings, legal or otherwise.

The report relies on focus group discussions, one-on-one meetings with stakeholders and workshop deliberations. It is assumed that the information provided during the course of the market study is not incorrect or misleading. The pharmaceutical sector data presented in the report has been provided by the Public Health Foundation of India (PHFI) and has been used as received. The Competition Commission of India assumes no responsibility or legal liability concerning the data’s accuracy, reliability or completeness.

This report is an exclusive property of the Competition Commission of India and shall not be used, either wholly or in part, without due acknowledgement.

Any comments/ feedback should be addressed to pharmastudy@cci.gov.in

| AIOCD | All India Organization of Chemists and Druggists |

| CCI | Competition Commission of India |

| CDAG | Chemists and Druggists Association, Goa |

| CDSCO | Central Drugs Standard Control Organization |

| C&F | Clearing-and-Forwarding |

| CGHS | Central Government Health Scheme |

| CIF | Cost, Insurance and Freight |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease |

| CVD | Cardiovascular Diseases |

| DPCO | Drug Price Control Order |

| ESI | Employees’ State Insurance |

| FGD | Focus Group Discussion |

| FY | Financial Year |

| GDP | Good Distribution Practices |

| GMP | Good Manufacturing Practices |

| GST | Goods and Services Tax |

| LMICs | Low-and-Middle-Income Countries |

| MAPE | Maximum Allowable Post-Manufacturing Expenses |

| MAT | Moving Annual Total |

| MBP | Market-based Pricing |

| MNC | Multinational Company |

| MoU | Memorandum of Understanding |

| MRP | Maximum Retail Price |

| NCD | Non-Communicable Diseases |

| NOC | No-Objection Certificate |

| NPPA | National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority |

| NSQ | Not-Of-Standard Quality |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| OOPE | Out-of-Pocket-Expenditure |

| PAP | Patient Assistance Program |

| PHFI | Public Health Foundation of India |

| PIS | Product Information Services |

| PMBJP | Pradhan Mantri Bhartiya Janaushadhi Pariyojana |

| PTR | Price-to-Retailer |

| PTS | Price-to-Stockist |

| R&D | Research and Development |

| RMSC | Rajasthan Medical Services Corporation |

| SU | Standard Unit |

| TNMSC | Tamil Nadu Medical Services Corporation |

| US FDA | United States Food and Drug Administration |

| WHO-GMP | World Health Organization – Good Manufacturing Practices |

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

1. The Competition Commission of India (CCI/ Commission) conducts market studies to better understand sectors, markets, or business practices through proactive engagement with stakeholders. These studies offer an opportunity to assess competition and competition barriers beyond individual firm behaviour and complement the Commission’s enforcement and advocacy work. Given the information asymmetry and agency problems that characterise the pharmaceutical sector, market systems do not self-organise using the force of free markets.1 Hence, any market system design must be mindful of these inherent characteristics.

2. In the past twelve years of the antitrust enforcement regime in India, the Commission has received 432 cases from the pharmaceutical sector, pertaining mostly to the pharmaceutical distribution segment. The sector’s distinctive features with their attenuating effects on competition and the multitude of cases raising antitrust concerns prompted the Commission to take a closer look at the sector from a competition standpoint.

3. The first step in this endeavour was a workshop organised in 2018, which brought together representatives of all relevant stakeholders on a platform to deliberate over issues that may warrant attention for competition regulation purposes. The issues and recommendations that emerged from the discussions at the workshop were documented in a policy note.3

4. The instant market study, initiated in October 2020, was an attempt to delve deeper into a sub-set of issues that found mention in the policy note.4 With the overarching objective of understanding the factors that influence price competition in the pharmaceutical sector, the study focused on the specific realms of pharmaceutical distribution and the role of trade associations therein, trade margins and drug pricing, and the prevalence of branded generic drugs in India and its implications for competition. Since the pharmaceutical sector is a regulated sector, the study also attempted to explore the areas of interface between regulation and competition with a view to ascertain the Commission’s advocacy priorities.

5. The study comprised i) primary (qualitative) research/stakeholder consultation conducted through one-on-one meetings and focus group discussions (FGDs) with representatives of pharmaceutical companies, stockists, pharmacists, e-pharmacies, trade associations, sector experts, doctors, and regulators; and ii) secondary (quantitative) research consisting of empirical analysis of pharmaceutical sector data. Ninety-nine market participants and experts individually shared their views/perspectives, while a large number of market participants were represented through their associations in the FGDs. A public notice was also issued to encourage wider stakeholder participation. While the study participants’ views were sought on research questions pertaining to the sector as a whole, the secondary research/ data analysis focused on drugs belonging to the six therapeutic categories of pain/ analgesics, anti-diabetes, cardiovascular diseases (CVD), anti-cancer, anti-biotics, and vitamins/minerals. The Public Health Foundation of India (PHFI) was the implementation partner for the study.

6. The focus areas of the study were taken up for deliberation in a multi-stakeholder workshop titled ‘Competition Issues in the Pharmaceutical Sector in India’ held on August 27, 2021. The workshop brought together representatives of different stakeholders and helped gather additional insights from different perspectives on the issues being studied.

7. This report summarises the main findings of the study and is structured as follows. The study findings with respect to generic drugs competition are summarised in Chapter 2. This chapter focuses on the prevalence of branded generics in India and its implications for generic competition and drug prices. Chapter 3 presents a summary of the findings with respect to the pharmaceutical distribution landscape, divided into three subthemes, viz. i) drug distribution and trade association practices ii) trade margins and iii) online pharmacies. The observations of the Commission, based on the study findings, are presented in Chapter 4.

CHAPTER 2

STUDY FINDINGS: BRANDED GENERIC DRUGS AND COMPETITION

8. Pharmaceuticals contribute 43.2% to the total out-of-pocket expenditure (OOPE) on health in India.5 This makes it the single largest contributor to OOPE, which accounts for an estimated 62.7% of total health spending in the country.6 Thus, prices of pharmaceuticals have a significant bearing on access to healthcare. While around 17.7% of the pharmaceuticals market in India (in terms of value) is under price regulation,7 competition is expected to be the key source of price discipline for the rest of the market.

9. Patented/originator drugs8 are insulated from competition for the life of the patent, in order to yield an assured return on R&D investments. After the expiry of patent protection, price competition from generic substitutes can generate significant cost savings for consumers. Generic drugs (‘generics’) play an important part in creating the competitive pressures that enable keeping prescription drug prices low, thereby reducing healthcare costs and improving access. By definition, generics9 have active ingredients that are identical to the patented/originator drug and are low cost, functionally undifferentiated products, which make generic markets structurally highly competitive.

10. India has a dynamic generic drugs industry, which is the largest supplier of generic drugs globally.10 The pharmaceutical market within India predominantly comprises generics, which account for around 97% of drug consumption in the country in terms of value. However, only about 10% of the drugs in the domestic market are unbranded/generic generics, marketed with just their chemical names as commodity generics; these drugs are largely procured and dispensed in public health facilities. 87% of drugs dispensed in India are so-called branded generics, i.e., generic drugs sold with brand names.11 The market for ‘branded generics’ is a phenomenon almost unique to India.

11. The market study intended to gauge the implications of the prevalence of branded generics for competition and pharmaceutical prices in India. The purpose was to gain an understanding of competition dimensions in the generics market with a view to identify potential areas for promoting effective price competition in generics that can benefit consumers and improve access to affordable healthcare. The main findings, based on empirical analysis/ secondary research and stakeholder consultation, are summarised in this chapter.

PHARMACEUTICAL SECTOR IN INDIA

12. India’s pharmaceutical growth trajectory has been spectacular in the last few decades. From being a net importer of drugs in the 1970s to becoming one of the major exporters of drugs and vaccines, India now ranks third and thirteenth globally in terms of volume and value,12 respectively. From a turnover of INR 1,750 crores in 1990, the drug industry’s turnover witnessed tremendous rise to INR 2.89 lakh crores in 2019–20, of which exports accounted for half the turnover.13 Rapid and significant improvement in manufacturing processes to enhance drug quality has resulted in a scenario where, currently, the largest number of US FDA-approved facilities worldwide are in India, totalling about 665,14 in addition to 1,400 WHO GMP-approved plants, and about 253 European Directorate of Quality Medicines-approved production plants.15

13. Table 1 highlights the combined retail market in India consisting of both branded generics and patented medicines. By value, retail sales worked out to INR 141,102 crores for the 12-month period of August 2019–July 2020, in which both cardiac and anti-infective segments accounted for 13% each, followed by gastro-intestinal (11%), anti-diabetic (10%), vitamins/minerals (9%) and the rest (44%). In terms of volume, cardiac accounted for the highest share (17%), followed by gastro-intestinal (16%), pain/analgesics (10%), hormones (9%), anti-diabetic (9%), vitamins/ minerals (9%) and the rest (30%).

Table 1: Sales Value and Volume of Medicines, India, July 2020

| THERAPY | VALUE | VOLUME | ||

| AREA | In Crores | In Percent | In SUs | In Percent |

| CARDIAC | 18877.12 | 13.38 | 33738.91 | 17.19 |

| ANTI-INFECTIVES | 18755.47 | 13.29 | 13151.77 | 6.70 |

| GASTRO INTESTINAL | 15576.46 | 11.04 | 32050.51 | 16.33 |

| ANTI DIABETIC | 14355.33 | 10.17 | 17313.04 | 8.82 |

| VITAMINS / MINERALS / NUTRIENTS |

12172.79 | 8.63 | 17227.07 | 8.79 |

| RESPIRATORY | 11001.27 | 7.80 | 16246.96 | 8.28 |

| DERMATOLOGIC | 9469.98 | 6.71 | 2128.16 | 1.08 |

| PAIN / ANALGESICS | 9426.01 | 6.68 | 19035.37 | 9.69 |

| NEURO / CNS | 8715.51 | 6.18 | 15583.31 | 7.94 |

| GYNAECOLOGICAL | 5517.47 | 3.91 | 3429.43 | 1.74 |

| ANTI-NEOPLASTICS | 2860.66 | 2.027 | 434.64 | 0.22 |

| HORMONES | 2639.77 | 1.87 | 17834.97 | 9.08 |

| OPHTHAL / OTOLOGICALS | 2424.73 | 1.72 | 530.99 | 0.27 |

| VACCINES | 2233.38 | 1.58 | 117.69 | 0.05 |

| UROLOGY | 1968.81 | 1.39 | 1758.04 | 0.89 |

| BLOOD RELATED | 1663.45 | 1.18 | 1403.97 | 0.71 |

| STOMATOLOGICALS | 777.80 | 0.55 | 135.38 | 0.06 |

| SEX STIMULANTS / REJUVENATORS |

739.63 | 0.52 | 551.09 | 0.28 |

| ANTI MALARIALS | 587.68 | 0.42 | 815.10 | 0.41 |

| OTHERS | 1338.24 | 0.95 | 2755.46 | 1.40 |

| Total Market | 141101.56 | 100 | 196241.88 | 100 |

Source: PHFI estimation from PharmaTrac Database, July 2020

Note: SUs indicate Standard Units, each SU denoting one unit of tablet, capsule, ampule, etc.

PREVALENCE OF BRANDED GENERICS

14. There were 47,478 brands associated with 2,871 formulations in the pharmaceuticals market in India during August 2019–July 2020, implying the presence of 17 brands on an average for every formulation. The number of formulations, brands, and manufacturers vary across therapeutic categories. A relatively larger number of brands are typically present in markets with a larger number of formulations. In some therapy areas, the number of brands created are disproportionately larger than the number of formulations. In niche areas, there are fewer brands in proportion to their formulation numbers. Vitamins/minerals and sex stimulants display higher brand creation, with the former standing out with 37 brands per formulation and, the latter with 19 brands on an average for each formulation. Vaccines and anti-neoplastic medication markets exhibit less brand creation, with five and seven brands per formulation respectively.

Table 2: Number of Formulations, Brands, and Brands per

Formulation, July 2020, India

| THERAPY AREAS | No. of Formulations | No. of Brands |

No. of Brands Per Formulation |

| GASTRO INTESTINAL | 305 | 5551 | 18 |

| ANTI-INFECTIVES | 290 | 5349 | 18 |

| CARDIAC | 283 | 3668 | 13 |

| DERMATOLOGIC | 281 | 4227 | 15 |

| PAIN / ANALGESICS | 275 | 4508 | 16 |

| RESPIRATORY | 271 | 3788 | 14 |

| NEURO / CNS | 216 | 3518 | 16 |

| OPHTHAL / OTOLOGICALS | 187 | 1666 | 9 |

| VITAMINS / MINERALS / NUTRIENTS |

141 | 5236 | 37 |

| ANTI-NEOPLASTICS | 130 | 895 | 7 |

| GYNAECOLOGICAL | 122 | 1808 | 15 |

| ANTI DIABETIC | 91 | 1661 | 18 |

| BLOOD RELATED | 66 | 613 | 9 |

| HORMONES | 40 | 528 | 13 |

| UROLOGY | 35 | 472 | 13 |

| VACCINES | 34 | 155 | 5 |

| ANTI MALARIALS | 19 | 208 | 11 |

| STOMATOLOGICALS | 19 | 320 | 17 |

| SEX STIMULANTS / REJUVENATORS |

9 | 174 | 19 |

| OTHERS | 57 | 3133 | 55 |

| TOTAL MARKET | 2871 | 47478 | 17 |

Source: PHFI estimation from PharmaTrac Database, July 2020

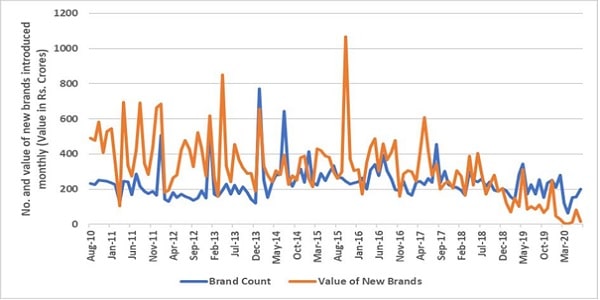

15. On an average, in the past one decade, about 235 drug brands have been introduced monthly, with a value of Rs. 318 crores. Annually, this translates into an average of 2,827 brands with a value totalling Rs. 3,810 crores.

Chart 1: Number and Value of New Brands Introduced Monthly,

India, 2010–20

Source: PHFI estimation from PharmaTrac Database, respective years

16. The average number of brands per formulation across therapy areas hides the stark variation observed within each formulation. In fact, the number of brands varies considerably even between different strengths and doses. In the anti-diabetes category, for instance, one of the popular combination drugs, namely glimepiride + metformin (Tablet, 500 mg), remains the top pick in the industry, with about 137 brands of 120 companies present in the market. Rosuvastatin (Tablet, 10 mg), a cholesterol–lowering agent, is marketed through 127 brands by 105 companies.

17. The data also corroborates brand proliferation by pharmaceutical companies, i.e. companies offering a portfolio of different brands of the same formulation with identical dose and strength. For instance, 15 companies were found to produce two different brands of glimepiride + metformin (Tablet, 500 mg). In rosuvastatin (Tablet, 10 mg), three brands of the same formulation are marketed by four companies. In other mature markets, such as amoxicillin & clavulanic acid, a combination antibiotic, there are multiple instances of five to six brands being supplied by the same company for the same formulation of same dose and strength. In multivitamin & minerals tablet, as many as 46 companies have two brands each, while 15 others were found to have three brands each. In this category too, multiple instances of the same company having five to six brands were observed. Thus, in the pharmaceutical market in India, as the data corroborates, product differentiation is introduced through brand differentiation even in generics, which are ostensibly homogeneous commodities and functionally interchangeable.

PRICING OF BRANDED GENERICS

18. To ascertain the effect of brand differentiation on the pricing of branded generics, price dispersion across brands of different companies and price discrimination across brands of same molecules marketed by same companies was examined.

19. A considerable price difference was observed between brands of a particular generic formulation marketed by different firms. To illustrate, one of the top selling formulations in the antibiotic category, namely, amoxicillin + clavulanic acid (Tablet, 125/500 mg), is currently sold by 217 companies under 292 brands. Substantial price variation was observed between companies selling different brands, ranging from Rs. 40 to Rs. 336 for a pack of six tablets.

20. Notable variations in price were also observed between brands marketed by the same company. For instance, the prices of glimepiride + metformin charged by a company for its two brands were Rs. 1 and Rs. 6 per tablet (Rs. 10 and Rs. 60 per pack of 10). One company which manufactures amoxicillin + clavulanic acid (125/500 mg, tablet), prices of two brands marketed by it stood at Rs. 18.27 and Rs. 73.17, resulting in a price variation of 120%.16

21. The price range across brands was examined for 54 formulations.17 23 formulations witnessed a price difference in the range of 150–200% across brands, while among 11 formulations the price difference varied between 100– 150%. The number of formulations in which price variation across brands ranged between 50–100% was about 12, followed by six formulations whose price variation was 10–50% and the remaining two medicines witnessed a price variation of 1–7%. For instance, paracetamol (150 mg) injection is sold at as low as Rs. 3.70 against a high of Rs. 124 per injection. Metformin, an anti-diabetes drug, is pitched at a price of Rs. 28 on the higher side against Rs. 1.30 per tablet in the same private retail segment. The highest-priced brand of atorvastatin (10 mg) is sold at Rs. 7.4 per tablet whereas the same is also sold at Rs. 2 per tablet. The lowest-priced amoxicillin (250 mg), an antibiotic, is priced at Rs. 0.40, while the highest-priced brand is sold at Rs. 8.20 per tablet. As far as therapeutic categories are concerned, price difference between the lowest-to-highest priced brands within a molecule ranged between 7–154% for anti-cancer, among analgesics within a range of 83– 199%, among anti-diabetes 150–183%, among cardiovascular drugs 1–200%, across antibiotics 31–192% and across vitamins/minerals 17–196%.

Price and Market Share

22. Market leaders in the pharmaceutical sector, even in the presence of a large number of firms and brands, charge prices that are relatively higher than other market participants, especially those with lower market share. One of the top selling anti-diabetic drugs, glimepiride + metformin (2/1000 mg) tablet, is sold by the market leader (firm with the highest market share in the formulation, measured by sales value) at Rs. 9.97 per tablet, while the market laggard (firm with the least market share in the formulation, measured by sales value) prices it at Rs. 1.53 per tablet, yielding a price difference of 147%. Human premix insulin, another anti-diabetic medicine, is sold by the market laggard at Rs. 15.42 per cartridge against the market leader’s price of Rs. 96.67 per cartridge, resulting in a price difference of 145%. Diclofenac (100 mg), an analgesic, recorded a price variation of 172%, with the market leader and laggard prices at Rs. 10.87 and Rs. 0.83 per tablet respectively. The price difference in amikacin antibiotic injection (500 mg) was reported to be 125%, underscoring significant price variation between the market leader price at Rs. 46 against the market laggard price of Rs. 10.62 per injection. The evidence suggests that the price charged by the market leader, measured by sales value, remains highest or among the highest, whereas the prices of lowest selling drug remain the least, or among the least.

Table 3: Market Leader and Market Laggard Prices, Value by Moving

Annual Total (MAT), July 2020, India

S.

|

SUBGROUP |

Drug Type |

Strength |

Market Leader

|

Market Laggard

|

||

Value July 2020 |

MRP Per

|

Value July 2020 |

MRP Per

|

||||

1 |

GLIMEPIRIDE + METFORMIN |

TABLET |

2/1000 MG |

456336770 |

9.97 |

852.5 |

1.53 |

2 |

HUMAN PREMIX INSULIN |

CARTRIDG E |

100 IU |

1804440320 |

96.67 |

830829.6 |

15.42 |

3 |

GLARGINE |

CARTRIDG E |

100 IU |

4029480200 |

240.85 |

22181719.0 |

198.27 |

4 |

SITAGLIPTIN |

TABLET |

100 MG |

1202422700 |

45.00 |

193941240.0 |

44.95 |

5 |

VILDAGLIPTIN + METFORMIN |

TABLET |

50/1000 MG |

921623730 |

21.20 |

5747.0 |

8.45 |

6 |

VOGLIBOSE |

TABLET |

0.3 MG |

397985970 |

12.50 |

63 |

2.63 |

7 |

ATORVASTATIN + ASPIRIN |

CAPSULE |

10/75 MG |

1370826000 |

3.34 |

45009.0 |

2.25 |

8 |

CLOPIDOGREL |

TABLET |

75 MG |

528096510 |

7.75 |

49.6 |

6.25 |

9 |

ROSUVASTATIN |

TABLET |

10 MG |

1214848300 |

16.35 |

156 |

4.88 |

10 |

TELMISARTAN |

TABLET |

40 MG |

1693869200 |

7.22 |

32.5 |

5.80 |

11 |

TICAGRELOR |

TABLET |

90 MG |

1244669700 |

30.00 |

55000.0 |

25.00 |

12 |

ACECLOFENAC + PARACETAMOL +SERRATIOPEPTI DASE |

TABLET |

100/325/15 MG |

2092835900 |

9.30 |

92.9 |

6.50 |

13 |

DICLOFENAC |

INJECTION |

75 MG |

1042783700 |

30.42 |

1712.0 |

5.77 |

14 |

DICLOFENAC |

TABLET SR |

100 MG |

893125230 |

10.87 |

19.9 |

0.83 |

15 |

IBUPROFEN + PARACETAMOL |

TABLET |

400/325 MG |

1657991600 |

1.73 |

10.6 |

1.32 |

16 |

PIROXICAM |

TABLET DT |

20 MG |

1044462900 |

11.89 |

3384.7 |

5.50 |

17 |

THIOCOLCHICOS IDE +ACECLOFENAC |

TABLET |

4/100 MG |

438111840 |

18.15 |

1066.5 |

14.81 |

18 |

AMIKACIN |

INJECTION |

500 MG |

1525060800 |

46.00 |

8.5 |

10.62 |

19 |

AMOXYCILLIN + CLAVULANIC ACID |

INJECTION |

1000/200MG |

316293450 |

68.82 |

3 |

16.00 |

20 |

AMOXYCILLIN |

CAPSULE |

500 MG |

740305690 |

7.08 |

83.7 |

3.49 |

21 |

CEFUROXIME |

TABLET |

500 MG |

1222536900 |

107.75 |

138.7 |

47.50 |

22 |

MEROPENEM |

INJECTION |

1000 MG |

1062786600 |

2979.00 |

1694 |

2117.50 |

23 |

CALCIUM + CHOLECALCIFER OL |

TABLET |

500MG/250I U |

2171785900 |

6.59 |

29.4 |

4.98 |

24 |

GINSENG PRODUCTS |

CAPSULE |

788621940 |

10.00 |

27.6 |

8.50 |

|

25 |

PROTEIN SUPPLEMENTS |

POWDER |

472420110 |

1.33 |

54.7 |

0.50 |

|

26 |

VITAMIN B COMPLEX WITH VITAMIN C ONLY |

CAPSULE |

3047938000 |

2.08 |

40.6 |

1.02 |

|

27 |

VITAMIN D + METHYLCOBALA MIN COMBINATIONS |

TABLET |

489541180 |

14.64 |

229459.0 |

13.90 |

|

28 |

VITAMIN E |

CAPSULE |

400 MG |

824910380 |

2.97 |

161 |

1.32 |

Source: PHFI estimation from PharmaTrac Database, July 2020

PRICE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN BRANDED GENERICS IN PRIVATE RETAIL MARKET AND PURE GENERICS IN PUBLIC PROCUREMENT MARKET

23. Price comparisons were made for the same 54 molecules spread across six therapeutic categories between branded generics in the private retail market and pure/unbranded generics in the public procurement market. Price data for the latter was obtained from two major public drug procurers [Tamil Nadu Medical Service Corporation (TNMSC) and Rajasthan Medical Service Corporation (RMSC)], while the former price was drawn from PharmaTrac dataset. Given the large price variation between different brands of the same molecule in the retail segment, the mean price in each formulation was taken into account for the purpose of price comparison. In percentage terms, the price variation between pure generics in public procurement and branded generics in the retail market across 54 molecules ranged from 8% to 190%, with the price difference for 45 molecules being more than 100%. Atorvastatin (10 mg tablet), a cholesterol–reducing agent, is procured by the procurement agency at Rs. 0.21 (21 paise) while the same is sold at Rs. 5.1 in the private retail segment, resulting in a 184% price difference. The manufacturer sells this product to stockists at a mean price of Rs. 3.43. Dobutamine HCL, an injection (250 mg) used in the treatment of cardiogenic shock and severe heart failure, is sold in the retail market at Rs. 286 against Rs. 14.28 paid by the procurement agency, whereas the manufacturer sells it to stockists at a mean price of Rs. 94. Significant price variation was observed across all categories of drugs. Price difference in the molecules considered in the analgesics category ranges between 61–167%. Anti-diabetics is one category where price difference was relatively high among the four molecules (glimepiride, gliben clamide, glipizide, metformin), with the difference ranging between 141–185%. The price difference for antibiotics was in the range of 82–193% whereas for vitamins/minerals, it was in the range of 160–190%.

24. Comparisons were also made between procurement price and price of lowest/highest–priced brands of generics available in the private retail market. Among 54 molecules under consideration, 20 belong to the category where price variation between the lowest priced brand and the generic molecule procured by public procurement agencies remains in the range of 101–180%. For instance, the price of the lowest–priced brand of zinc tablet (10 mg) in the retail segment is Rs. 3 per tablet against the procurement price of Rs. 0.16 (16 paise) per tablet, yielding a price difference of 180%. Price variation among 19 molecules is in the range of 50–100%. For instance, ampicillin (500 mg) injection, an antibiotic, is sold in the retail segment at Rs. 8 per vial (lowest–priced brand) against the procurement price of Rs.4.80 per vial. Among nine molecules, the price variation was observed to be in the range of 5–39%.

25. In the comparison between the highest–priced brand and procurement price, 46 out of 54 drugs demonstrate a price difference ranging from 107–197%. The highest–priced brand of metformin (500) tablet is sold in the retail market at Rs. 28 per tablet against Rs. 0.23 (23 paise) per tablet paid by the procurement agency. Similarly, paracetamol injection (150 mg) is procured by the procurement agency at Rs. 1.52 per injection whereas the highest–priced brand is pitched at Rs. 124 per injection. One of the narrowest price differences, 43%, was observed in the vincristine sulphate (1 mg) injection, administered to stop the growth and multiplication of cancer cells, where the highest–priced brand is sold at Rs. 54 per injection against the procurement price of Rs. 34.8 per injection. Further, it may be noted that only in six out of 54 drugs price difference between these two segments was in the range of 43– 99%, underlining the considerable price premium that the highest–priced brands are able to command in the market.

26. As evidenced by the data, despite the seemingly strong generic competition, gauged in terms of the number of players present in each therapeutic area and at the level of formulations/molecules, consumers in India ostensibly pay a premium for brands. Brand competition in the case of originator/patented drugs is based on relative quality and the value that a new drug creates for consumers. In that case, brand name is a means for product identification and awareness creation on the therapeutic merits that a drug offers above and beyond that of the other existing drugs in the same category. However, the same cannot plausibly hold true for generic drugs which, regardless of their brand names, possess the same active pharmaceutical ingredients as the originator medicine and are therefore expected to be interchangeable or identical in terms of non-price parameters such as safety and efficacy.

27. The secondary research findings were supplemented with primary research through stakeholder interviews to obtain greater clarity on factors driving brand competition in generic drugs in India. Stakeholders’ views were sought, inter alia, on i) why brand competition, which is premised on product differentiation, governs the market of generics that are supposed to be bio-equivalents to the originator/patented drugs and are thus considered homogeneous, ii) what explains the price dispersion observed across brands in the market of same generic molecules and the significant price difference that exists between unbranded/generic generics and branded generics and iii) how price competition can be promoted in the market for generic drugs in India.

ROLE OF QUALITY IN BRAND COMPETITION

28. The feedback received, in large part, centred on the aspect of alleged heterogeneous quality of drugs in terms of their safety and efficacy profile. However, respondents were divided in their opinion of whether heterogeneity in drug quality was actual and significant, which justified quality signaling through brand names, or only perceived, which was reinforced through the drug companies’ marketing strategies to command brand premium on prices. On the one hand was a section of respondents who were of the view that brands simply enabled niche markets to be created by pharmaceutical companies to retain and exercise pricing power, which would otherwise be constrained by the homogenous commodity nature of generics. According to them, a perception of higher quality of certain brands and that of a price– quality correlation is fostered by pharmaceutical companies through their brand promotion measures, with no real quality differential between different branded generic versions or between unbranded generic and branded generic versions of the same molecule. They attributed the primacy of brand competition in generics to the three key underlying factors, viz., information asymmetry regarding drugs vis-à-vis consumers of drugs, unobservable quality of drugs and prescription of drugs by brand names rather than by generic names. As consumers are not in a position to make an informed choice and the quality/efficacy of drugs is intrinsically unobservable, they follow doctors’ brand prescriptions, which are often influenced by aggressive brand promotion by pharmaceutical companies. This, according to them, reduces the price elasticity of demand, deters price competition, and allows setting high prices, price discrimination and extraction of consumer surplus.

29. These respondents refuted the contention that heterogeneous quality of drugs was a significant enough issue in India as to warrant and justify quality signaling through brand names and prices. Neither did they concur with the proposition that brand names were reliable proxies for drug quality and that higher prices signaled better quality. The statutory requirements, inspections and approvals relating to drug quality remain identical in the country, with the requirement that drug makers must be conforming to Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP). Thus, it was argued that there was no reason to believe that quality/efficacy of approved unbranded/generic generics would be inferior to that of their branded counterparts or that drug quality/efficacy could indeed vary significantly across brands of the same generic molecule. According to them, the trend of multiple brands of the same molecule being marketed by the same company at different price points runs counter to the proclaimed brand name-quality correlation. They added that brand names of generic drugs can hardly signal quality, as several prominent players who market these brands often get their products manufactured through third–party or contract manufacturing, and the same third-party manufacturer accepts orders from multiple pharma companies. They further felt that the perception regarding pure generics sold without brand names being of low quality was also unfounded; often, the same companies produce unbranded as well as branded versions of the same generic drugs at the same plant. Generic versions, without brand names, are marketed in countries with strict regulatory standards. Thus, branding, according to this set of respondents, is merely a way for pharmaceutical companies to create artificial product differentiation and niches even in off-patent drugs to be able to command brand premium on prices and still sustain high shares in the domestic market.

30. On the other hand, another set of respondents was of the view that quality did vary across drugs; not all branded versions of the same generic molecules available in the market were equally safe and efficacious. According to them, while price competition and access to affordable drugs is important, it has to be seen in conjunction with the quality of drugs, which is essential to achieve the desired treatment outcomes. Branding of generics is viewed as a necessary evil by this set of respondents. They believe that because pharmaceutical safety and efficacy are unobservable, prescription patterns reflect a preference for brands with known clinical experience of physicians. Further, they stated that, while prescriptions generated with brand names indeed help create brand stickiness with its attendant price fallouts, prescription by generic chemical names could lead to the consumption of less efficacious or low–quality brands, denying the patients effective therapy. As per extant legal provisions, substitution by retailers/chemists is unlawful in India and retailers are not allowed to substitute a prescribed brand with another brand containing the same substance.18 However, prescription by generic chemical names shifts the agency to retailers/chemists, enabling them to choose and dispense from available brands that which offers them the highest margin, regardless and unaware of its efficacy. In a scenario where quality is homogenised across brands, retailers’ discretion in dispensing drugs should not raise concern from the standpoint of therapeutic benefits. However, this set of stakeholders, including some of the medical practitioners who participated in the study, did not attest to the homogeneity of drugs available in the market in terms of their safety and efficacy. Representatives of the manufacturing industry underlined the branding of generic drugs as reflective of quality competition and as a means to highlight actual product differentiation for addressing the entrenched concerns around the quality of drugs. They further claimed that the branded generics market was not impervious to price competition, and that similarly placed companies in terms of their product portfolio and brand image did compete on price.

31. In view of the varied responses received on the quality aspect, government data [Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO)] Drug Alerts, monthly data, March 2019 to April 2021, on ‘not of standard quality drugs’ was referred to. Irrespective of whether a drug is branded or not, any pharmaceutical product which does not meet the specifications of pharmacopoeia, including quality parameters, is considered ‘not of standard quality’ (NSQ). The NSQ or sub-standard drugs fail to meet the desired levels of standards for several reasons: assay, disintegration, delayed dissolution, contamination, presence of foreign matter, fungus growth, non-dispersible lump formation, addition of non-permissible colours, toxicity, sterility, etc. On an average, the share of drugs failing to meet the standards of pharmacopoeia, was approximately 3% during March 2019 – April 2021. This data pertains to drugs sold in the retail market comprising largely branded generics.

32. A more comprehensive evidence comes from a national survey conducted by the Government of India during 2014–16, drawing a sample of 47,954 drugs involving retail chemists and government pharmacies.19 About 72% of the samples were drawn from private retail outlets, about 18% from government distribution points (State Government Medical Store Depots, Civil/District Hospital Stores, CGHS dispensaries, and ESI dispensaries), while the remaining 10% was sourced from ports (imported drugs). One of the key objectives of this survey was to investigate the magnitude of NSQs and spurious drugs in the country. On an average, approximately 3% of all sampled branded generics turned out to be sub-standard, and roughly 0.003% spurious. The key reasons for test failure were dissolution (25%), followed by assay (23%) and description issues (12%). State-wise NSQ magnitude ranged between 0–9%, with an average of 3% for branded generics. As per the survey, the presence of NSQs in unbranded/generic generics was higher. Approximately 10% of all samples tested for NSQ in government sources failed, indicating a higher share of medicines failing quality test. The key reasons contributing to NSQ test failure in the government facilities were assay (24%), dissolution (22%), related substances (14%), etc. Here, too, the extent varied across states, ranging up to 12% in some states. In states, that follow pooled procurement systems, the relative share of substandard drugs was found to be lower in comparison. Some experts and stakeholders however pointed to the limitations of such sample surveys for quality assessment mainly on account of small sample size and the inability of the tested samples to represent variability across batches and thus cautioned against drawing generalised conclusions from one-off surveys for policy purposes.

33. The quality variance in drugs was attributed by stakeholders largely to the non-uniform enforcement of quality standards across states. According to them, generic competition in the market can be steered from non-price to price dimension only when all generic drugs available in the markets across the country, with or without brand names, are perceived to be of comparable efficacy. Medical practitioners who participated in the study urged for stringent and uniform regulatory evaluation of all drugs before they are marketed. They further suggested the introduction of an institutional quality signaling mechanism, such as standard-compliance marks, to provide them with the necessary confidence for making prescriptions by generic names as well as improve public perception of generic drugs as a whole.

ROLE OF TRADE GENERICS

34. The stakeholder interviews revealed that what is generally understood as generic drugs in the retail trade is a sub-set of branded generics, referred to by most retailers interchangeably as ‘generics’ or ‘trade generics’. Branded generics and trade generics are not distinguishable on the basis of any objective criteria, both being generic versions of off-patent originator drugs, carrying brand names, nor are these drugs identified or captured as a distinct category in the available pharmaceutical sector databases. Those interviewed for the study clarified that the difference was in terms of marketing channels or business models employed by drug makers for these two categories of drugs. Generic drugs that are marketed using the route of brand promotion through the field force of medical representatives (who engage with the medical community to apprise them on the therapeutic attributes of brands/ drugs) are referred to as branded (generic) drugs in trade parlance. These drugs are prescribed by doctors and distributed through the conventional distribution channel comprising C&F agents, super stockists/ stockists, sub-stockists and retailers/chemists. On the other hand, trade generics, commonly referred to as generics, are known to be drugs which entail considerably higher retail margin and are supplied by pharmaceutical companies directly to chemists, hospital–managed pharmacies, and doctor–run pharmacies. As suggested by feedback from stakeholders, trade generics are not a source of price competition in the branded generics market, since the price paid by consumers, i.e., the MRP of trade generics, are not lower than branded generics; rather, these are reportedly often pitched at higher price points to enhance retailers’ margins and incentivise sale. The issue of trade margin and its implications for drug pricing are discussed in detail in Chapter 3.

AVAILABILITY OF UNBRANDED/ GENERIC GENERICS

35. Interaction with stakeholders confirmed the secondary research finding with regard to the unavailability of unbranded/generic generics in the private retail market in India. Prescription practices largely by brand names lead to low demand for unbranded generic drugs in the domestic retail market, which explains the supply side response from manufacturers in making such drugs available only to public health facilities. Most government drug procurement agencies such as the Tamil Nadu Medical Services Corporation, Rajasthan Medical Services Corporation, Kerala Medical Services Corporation, Central Government Health Scheme, and Employees State Health Insurance, buy drugs that are primarily generic-generics, if generic equivalents are available. With an objective of making quality generic medicines available at affordable prices to all, the Pradhan Mantri Bhartiya Janaushadhi Pariyojana (PMBJP) was launched by the Department of Pharmaceuticals, Ministry of Chemicals & Fertilisers, Government of India, in November 2008. Under the scheme, dedicated outlets known as Janaushadhi Kendras were opened to provide generic medicines at affordable prices. As of 06.08.2021, 8,012 Janaushadhi Kendras are functional across the country, with their product basket comprising 1,451 drugs and 240 surgical items. The scheme is implemented by the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Bureau of India.20

36. A near-consensus emerged from the study regarding the significant role that Janaushadhi Kendras can play in enhancing competition and improving the availability and awareness of affordable generic drugs in the market. The respondents also highlighted how government endorsement of the Janaushadhi Kendras contributes to confidence building and acceptability of unbranded generic drugs, both in urban and rural areas. However, it was also pointed out by certain private retailers who participated in the study that some Janaushadhi Kendras stocked and sold branded generic drugs alongside pure generics to make their business viable. Shortage of stock at the Janaushadhi Kendras was cited as an issue that affected the smooth operation and reliability of these stores. Besides strengthening the supply chain management,21 most respondents pointed to the need for increased visibility and, wider network of these Janaushadhi Kendras, backed by large-scale measures to improve public perception of generic drugs. Some suggested opening these stores alongside regular retail pharmacies near corporate hospitals and in commercial areas where private retail chemists operate. Some respondent retailers also urged allowing the shop-in-shop model, wherein private retailers would provide dedicated selling space for the sale of unbranded generic drugs under the Janaushadhi scheme.

37. The Janaushadhi model has led to the launch of generic-only private retail chains in the country. These chains reportedly procure/contract manufacture generic medicines and sell them unbranded through retail outlets at price points relatively lower than branded generic medicines. Still in its nascence, if this trend gathers momentum, it has the potential to complement Janaushadhi in improving the uptake of unbranded generics in the country, subject to compliance of quality checks, as done for drugs sold at Janaushadhi Kendras. Among the pre-requisites for this model to be viable and scalable, the suggestions made by stakeholders included mention of generic names of molecules in doctors’ prescriptions and large-scale government efforts for building public trust in unbranded generics.

CHAPTER 3

STUDY FINDINGS: DRUG DISTRIBUTION AND COMPETITION

38. Distribution network plays a critical role in making pharmaceutical products available to consumers. Drug supply chain involves a number of stakeholders from manufacturers who produce drugs to intermediaries at wholesale and retail levels. Competitive markets at every stage of the pharmaceutical supply chain, i.e., manufacturing, wholesale, and retail, can contribute effectively and significantly to the public policy goal of making drugs affordable and accessible. Likewise, competition distortions at any stage of the supply chain can act as a major hindrance in this pursuit.

39. The Commission, over the past years, has received and adjudicated cases relating to alleged anti-competitive practices in the distribution segment, pursued by the industry/trade associations. Contravention of the provisions of the Competition Act, 2002 (the Act) was established in cases where trade associations were found to mute competition by exercising collective control over entry, supply, and competition. Specifically, the practices found to have the effect of limiting competition included i) mandatory requirement of no-objection certificate (NOC) from the associations for the appointment of stockists by manufacturers, which had the effect of limiting stockists/wholesalers in a given geographical area and ii) mandatory Product Information Service (PIS) charges levied by associations for the introduction of new drugs in a particular geographical territory. The other issues that attracted antitrust scrutiny relate to collective determination of trade margin by associations and associations’ control over discounts offered at wholesale and retail levels of sale.

40. In this background, the study intended to gather feedback from industry participants on the current state of affairs vis-à-vis these practices, particularly in light of the contravention decisions issued by the Commission. Further, as documented in the policy note,22 stakeholders present at the 2018 workshop raised a concern regarding high trade margins in India contributing to high drug prices. An attempt was made in the study to examine the range of margins at the wholesale and retail levels that prevail in the industry for drugs belonging to the identified therapeutic categories as well as to elicit stakeholder views on the issue of trade margins. Online pharmacies were the other focus area of the study to understand the emerging competition landscape in pharmaceutical distribution in view of the increasingly important role that these e-commerce entities are likely to play. A brief description of the distribution/supply chain for pharmaceutical products in India, followed by the key findings on these three sub-themes are presented in this chapter.

41. In India, there are about 3,000 pharmaceutical companies, whose products are manufactured in over 10,563 industrial units23, supplied through 65,000 stockists, with a strong penetration of private retail chemists numbered about 9 lakhs. Given the country’s size in terms of geography and population as well as a fragmented and vast private health sector, the task of the pharmaceutical supply chain is onerous. The supply chain function includes distribution tasks that range from consignee agent for pharmaceutical companies, setting up and maintaining warehousing and cold chain management, transportation, debtors’ management, and reverse logistics and waste management.24 Once the consignment leaves manufacturers, in most cases, the first channel is Clearing and Forwarding Agents (C&F Agents), whose role is of a super distributor with functions such as i) providing storage facility; ii) executing supply order & maintenance of receivables from the stockist; iii) facilitating the company in providing sales record and sales tax details to government departments; and iv) providing the company with market information. For imported medicines, the CIF (cost, insurance, and freight) agents are the first level of contact from importers. Companies, particularly MNCs and large domestic companies, appoint C&F agents; C&F are de facto employed by the company to act on their behalf. Smaller companies use independent distributors/stockists to manage their supply chain. The super-stockists are generally vested with the responsibility of a large geographical region (one or few states depending upon size) with the core functions of inventory management. They are the authorized distributors to stockists and their functions include: i) to maintain adequate stocks; ii) to maintain a database with respect to sale and stock scenarios; iii) to provide details to the company about outstanding and receivables in respect of every stockist; iv) to facilitate reimbursement of credit note with respect to expiry and stock return; and v) to help gather market information that facilitates companies’ strategy and its competitors. On the other hand, stockists who are at the third level of distribution channel but confine their operations to district/taluka levels, sell the stocks to retailers and health institutions. Their functions are closely aligned to super-stockists with the difference that they are functional over a relatively smaller region. The role of a sub-stockist is confined to an even smaller area/region and acts as an intermediary between stockists and chemists. Finally, retailers provide last mile connectivity in the pharmaceutical supply chain who also serve as a face of the supply chain with the patients/customers. The core functions of a retailer

23 Government of India (2020), Invest India, National Investment Promotion and Facilitation Agency, Pharmaceuticals Sector. Accessed at http//investindia.gov.in/sector/pharmaceuticals are largely to do with providing the logistics of making medicines available to patients in the correct dosage and in time. Online pharmacies are fast emerging as a distribution channel for drugs, operating under different models, which are discussed later in the chapter. Large hospital chains and corporate institutions in the health space typically procure medicines directly from the manufacturer. Government procurement is also largely channeled through this route, wherein public procurers are able to negotiate directly with producers through public procurement mechanisms.

TRADE ASSOCIATION PRACTICES

42. As mentioned earlier, trade association practices, viz., mandatory requirement of NOC for appointment of stockists and mandatory payment of PIS charges for introduction of new drugs by pharmaceutical companies, have been held to be anti-competitive by the Commission in several cases pertaining to different states/districts of India. Most of the interventions of the Commission have been directed at the All India Organization of Chemists and Druggists (AIOCD) and its various member associations at the state and district levels. These cases before the Commission have shown that the entire supply chain of drugs is ‘self-regulated’ by the trade associations, resulting in market distortions. With the purported goal of self-regulation, the apex association and its local affiliates were found to essentially play a gatekeeper role at various levels of the distribution chain, making pharmaceutical markets impervious to the incentives of competition. In addition to enforcing the provisions of the Act, the Commission has also engaged in targeted advocacy and issued public notices highlighting the importance of fair and competitive conduct.25 The study intended to gauge the effect of these measures on the practices of associations through extensive interviews and discussions with all relevant stakeholders.

43. On the issue of NOC requirement for appointment of stockists, a majority of the respondents representing the direct stakeholders, viz., drug producers, stockists, chemists/retailers, and associations, informed that the mandatory requirement of obtaining NOCs from trade associations for the appointment of stockists/chemists no longer exists. About 78% of those who responded on this issue denied the requirement of NOC from trade associations. The rest, representing some pharmaceutical companies and individual stockists, maintained that the practice continued, with a majority of these respondents having specified the requirement of NOC to continue to be mandatory. On the issue of levying PIS charges for the introduction of new drugs, 70% of the respondents informed that the practice no longer continues. A majority of those who reported that the PIS charges continued to be levied maintained that these charges were now voluntary and not a mandatory imposition by the associations.

44. The association representatives, while confirming compliance with CCI orders, put forth their views in favour of these practices. These practices, according to them, were an offshoot of recommendations made by an expert committee set up by the government (Mashelkar Committee26), which required trade bodies to act as a “watchdog” against the supply of sub-standard and spurious drugs to the market. On PIS charges, their arguments centred on the benefits that the product information system delivers for both retailers and pharmaceutical companies by creating awareness among stakeholders about newly introduced drugs. They also referred to the statutory requirement of dissemination of product and price information by pharmaceutical companies and maintained that the PIS bulletin brought out by associations was a way to facilitate the same. They stated that, but for the PIS system, manufacturers would be required to reach out to all individual retailers, which would add significantly to their transaction cost. In this context, some also referred to the concurrence of pharmaceutical companies to this system which, according to them, was run with mutually agreed-upon ‘nominal’ charges paid by pharmaceutical companies. However, this view on PIS was refuted by some participant companies who considered the PIS charge as a sort of ‘market access’ fee imposed by associations. Some participant stockists found the charges to serve the mere purpose of revenue generation for associations as the stated purpose of information dissemination was taken care of by the field force, i.e., through medical representatives of pharmaceutical companies.

45. Overall, the stakeholder feedback received in the study suggests a significant positive impact of the Commission’s orders and advocacy initiatives, in terms of discontinuation of the NOC and mandatory PIS norms. Inputs received from a minority of participants averring continuation of the practices indicate that the practices may still be in force in some form in pockets.

TRADE MARGIN

46. One of the highly contested terrains underlying medicine prices and price regulation is the role of intermediaries in the supply chain and the associated mark-ups. Mark-up (or trade margin) is computed as the difference between the retail price of medicines and cost price of manufacturers (ex-factory price).

Thus, mark-up (trade margin) signifies costs in the supply chain including transport, storage, overhead costs, and a profit associated with each intermediary (wholesalers, stockists, sub-stockists and retailers). Margins attributed to the intermediaries at the wholesale and retail level contribute to the final price paid by consumers. In India, scheduled drugs (under Drugs Price Control Order, DPCO) attract a statutory trade margin of 24% – 16% for retailers and 8% for wholesalers. However, the DPCO does not specify the same for non-scheduled drugs, which account for around 82.3% of the medicines sold in the market27. Reportedly, companies generally follow a margin structure of 10% and 20% for wholesalers and retailers respectively for non-scheduled drugs while fixing/printing the MRP.

47. An independent analysis of price data for five therapeutic categories (excluding anti-cancer) was conducted as part of the study to ascertain the extent of trade margin in pharmaceuticals.28 From each of the five identified therapeutic classes, the top 30 formulations by value were taken to conduct this analysis. Considering all the brands in these 30 formulations, a total of 5,976 total unique strength and dosage forms were obtained – anti-diabetes (461), CVD (1,154), antibiotics (1,229), vitamins/minerals/nutrients (1,638), and pain/analgesics (1,494). By value, this worked out to about 41% of CVD market (Rs. 189 crores), 50% vitamins and minerals (Rs. 94 crores), 50% antibiotics (Rs. 122 crores), 57% analgesics (Rs. 149 crores), and 62% anti-diabetes (Rs. 144 crores). Brands with 1% and above market share were considered. The price points considered in the analysis were: manufacturers’ price, C&F (CIF) margin, wholesale margin, retail margin, and taxes. In the absence of manufacturers’ price in the PharmaTrac database from which data for this analysis was drawn, manufacturers’ price was obtained as a residual estimate, after all four price points ex–post were deducted from 100. C&F margins were taken to be 2% basis the responses received from interviews with stakeholders. Stockists’ margin was obtained after deducting PTS (Price-to-Stockist) from PTR (Price-to-Retailer), and retailers’ margin was estimated by deducting PTR (Price-to-Retailer) from MRP. Tax (GST) was taken to be 12% of the consumer price. 29 All margins are expressed in percentage terms, i.e., as percentage to final price (MRP). The time period of the analysis is August 2019 – July 2020.

Table 4: Sales Volume and Value of Top 30 Formulations, India, 2020

| THERA-PEUTIC CATEGORY |

NUMBER OF FORMU-LATIONS | UNIQUE STRENGTH & DOSAGE FORM |

SALES VOLUME |

SALES VALUE |

||

| Billion SUs | Share (%) | Billion INR | Share (%) | |||

| Anti-diabetic | 30 | 461 | 17.31 | 52.09 | 143.55 | 62.28 |

| Cardiovascular | 30 | 1154 | 33.74 | 40.56 | 188.77 | 41.56 |

| Analgesics | 30 | 1229 | 10.13 | 47.28 | 149.31 | 56.55 |

| Antibiotics | 30 | 1638 | 17.23 | 64.02 | 121.73 | 49.53 |

| Vitamins &Minerals |

30 | 1494 | 19.04 | 61.73 | 94.26 | 49.51 |

| Total | 180 | 5,976 | 97.45 | 697.62 |

Source: PHFI estimation from PharmaTrac Database, August 2019 to July 2020

48. At the aggregate level, ex-factory price in relation to customer price was found to account for the largest share, at about 49%. If C&F costs were added to manufacturer price, this would work out to about 51%. The median wholesale margin and retail margin were estimated to be around 9% and 28% of customer price respectively, taking taxes (GST) at 12% of customer price. In the anti-diabetes category, the margins were found to vary by injectables and solids, with the former attracting lower median retail margin of about 20% and the latter attracting 28.6% margin except three formulations. These three formulations attract 25% median retail margin. With respect to median wholesale margin, injectables and solids attracted approximately 6% and 7%, respectively. In the CVD medicines market, injectables attracted lesser median retail margin (23.8%, with a range between 18.9% and 55.6%) compared to 28.6% on all solids, with a range between 23% and 70.7%. The median wholesale margin for injectable CVD drugs remains high, at 37.9% for one formulation and 33.8% for the other, lying in the range of 3.6% to 46.7%. In case of solid CVD drugs, the median wholesale margin is 7.1%, with a range between 5.7% and 13.6%. As far as the category of analgesics is concerned, the median margin for retailers is 28.6% across injectables and solids, varying from 20% to 88.4% across formulations. In the category of antibiotics, median retail margin was found to be about 28.6% across injectables and solids, except for two single molecule antibiotics attracting 23.8%. The median retail margin varies from 15.5% to 79.2% across formulations in this category. The median margin for wholesalers stands at 7.1% for most antibiotic formulations except a few outliers in case of injectables. In vitamins and minerals, the median retail margin is 28.8%, varying from 17.5% to 32.2% across formulations. The median wholesale margin for this segment is approximately 7%, varying across individual formulations ranging from 4.5% to 21.4%.

49. Estimates from this exercise reveal that the median retail margin is significantly higher than the regulatory cap of 16% applicable to scheduled drugs. The data further corroborates that the median retail margin is even higher than 20%, which is often reported as the margin commonly set by manufacturers for non-scheduled drugs. The sample included both scheduled and non-scheduled drugs. The number of scheduled drugs included (in the sample comprising the top 30 formulations in each therapeutic category) was four in anti-diabetics, six in CVD, three in analgesics, ten in antibiotics, one in vitamins/minerals, and five in anti-cancer drugs.

50. Inputs received from parties interviewed for the study indicate that one of the key ways in which manufacturers compete to have their products stocked and sold by pharmacies is by offering them high margins. Despite the statutory restriction on brand substitution by retailers, they reportedly play a key role in influencing drug purchase owing to lax enforcement of the norm. High retail margins are set by manufacturers as financial incentives for chemists to stock and dispense their brands in the presence of multiple branded generic drugs available in the market for each molecule. Given their space constraint and/or the need to minimise cost, retailers/chemists cannot typically stock all brands available for a formulation. They have an interest in stocking brands that offer them the highest margins. For non-scheduled drugs outside the scope of price regulation, high retail margins can simply be ensured through higher MRPs. Thus, competition between manufacturers on retail margins does not imply competitive prices for consumers. Rather, this creates a systemic upward pricing pressure, eroding the benefits of generic competition at the manufacturing level and any cost savings that may accrue at the manufacturers’ end owing, inter alia, to increased productivity.

51. Trade generics, as discussed in the previous chapter, were pointed out by respondents as drugs that particularly entailed disproportionately high retail margins. While retail margin as an incentive mechanism may allow new manufacturers or manufacturers with limited product portfolios to enter and expand their market shares against incumbents with established brand image and wider product portfolios, competition on margins does not translate into competitive outcome for consumers in terms of lower price. Thus, sector experts who were interviewed for the study were of the view that competition focused on chemists and pursued through the trade generic versions of molecules should not be viewed as genuine competition aligned with consumer welfare. Hospital pharmacies and doctor-run pharmacies, as informed by a majority of the study participants, are a key route for the supply of these high margin, high MRP drugs. It was averred that, for in-patients, purchase of prescribed drugs from hospital pharmacies is often mandatory, which insulates hospital pharmacies from retail competition. Competition on margins between manufacturers without any competition at the retail end makes this structure impervious to any incentive to compete on the final price paid by consumers. They opined that particularly in such therapeutic categories for which hospital pharmacies are the key dispensers of drugs, and such medications which can be offered only in a hospital setting, margin competition leads to higher price of drugs. The doctor-run pharmacies, on the other hand, reportedly dispense brands prescribed by the owner-doctors, which too, entail higher retail margins. Thus, in these set ups, high margins create perverse incentives that influence prescription patterns as well.

TRADE MARGIN RATIONALISATION

52. Several regulatory measures have been implemented globally to control markups. This has taken the form of setting i) a fixed percentage mark-up, ii) a maximum mark-up, or iii) a regressive mark-up.30 A fixed percentage markup is reported to result in reduced prices of specific drugs but is likely to push up higher-priced medicines’ sales even when lower-priced generics are available. On the other hand, a regressive mark-up intends to dis–incentivise retailers from pushing higher-priced medicines by simply imposing lower mark-ups on them.31,32 A past study of 27 OECD nations suggested that all of them regulated pharmacy margins, while in 21 countries, wholesale margins were controlled. The capped mark-ups ranged between 2–21% for wholesalers and 4–50% for retailers. Substantial mark-up variation was observed in low-and-middle income countries (LMICs) ranging from 10–35% and 0–76% for wholesalers and retailers respectively.33 Such variations can be explained by differences between the public and private sector supply chain, differences arising from class or type of medicines under policy interventions.

53. Countries that implemented differential mark-up on a select group of medicines are limited and India is one among them.34,35 Medicine price capping in India since the 1970s distinguished between scheduled and non-scheduled drugs, in which only the former attracted margin capping, as per Drug Price Control Orders (DPCO). Previous price-capping mechanism followed Maximum Allowable Post-Manufacturing Expenses (MAPE), which included transport, storage, and mark-ups for wholesalers and retailers. The MAPE computation allowed for a capping of 16% and 8% for retailers and wholesalers. Although the DPCO 2013 shifted the mechanism of price capping from cost-plus based pricing to market-based pricing (MBP) mechanism, the underlying percentage mark-up for wholesalers and retailers remained the same.

54. In 2019, the National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority (NPPA), India’s drug price regulator, invoked Para 19 of the Drugs Prices Control Order, 2013 to rationalise trade margins in select anti-cancer drugs. Besides 59 anti-cancer medicines under price control as part of DPCO-scheduled formulations, 42 anticancer medicines (non-scheduled formulations) were brought under the ambit of trade margin rationalisation.36 In effect, this would cover about 72 formulations and 355 brands of oncology medicines. Under this price capping mechanism, trade margin was restricted to a maximum of 30%. This exercise of trade margin capping on oncology medicines was undertaken as a pilot for ‘Proof of Concept’ before further extension into other therapeutic segments.

55. Table 5 highlights the number of oncology formulations that are under trade margin rationalisation and the price effects. The data shows the magnitude of price decline ranging from no reduction to 70% and above. In terms of decline in average MRP (i.e., the end-user price at which consumer buys medicines from retail market), the largest decline is observed among nine formulations with reduction ranging from 10–20%. Seven formulations witnessed 1–5% and 5–10% fall in average MRP each. No reduction in price, because of trade margin ceiling, is witnessed among six molecules. One formulation is reported to have sustained more than 70% reduction in average MRP. In seven formulations, an increase in average MRP is observed. Significant number of molecules (10 each) experienced a fall in Price to Retailer (PTR) in the range of 1–5% and 10–20%. It is likely that when margin ceilings are specified, the largest influence is expected to be on PTR, given that retailers are reportedly receiving a margin (prior to ceiling regulation), which is many times that of stockists/wholesalers. Reduction in PTR to the extent of 20–30% and 30–40% was witnessed in six and eight formulations respectively. With respect to Price to Stockists (PTS), no reduction was witnessed in about nine formulations while nine molecules saw 1–5% fall in PTS.

Table 5: Price Effects of Trade Margin Regulation, India

| RANGE OF PERCENTAGE CHANGE | MEDICINES UNDER TRADE MARGIN REGULATION |

||

| No. of Formulation(MRP) |

No. of Formulation(PTR) |

No. of Formulation(PTS) |

|

| No Reduction (0%) | 6 | 7 | 9 |

| </=1% | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| >1 and </=5% | 7 | 10 | 9 |

| >5 and </=10% | 7 | 3 | 5 |

| >10 and </=20% | 9 | 10 | 7 |

| >20 and </=30% | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| >30 and </=40% | 5 | 8 | 8 |

| >40 and </=50% | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| >50 and </=60% | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| >60 and </=70% | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| >70 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Price Increase | 7 | 1 | 2 |

| N/A | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| Total | 67 | 67 | 67 |

Source: PHFI estimation

56. Stakeholders shared their views on trade margin rationalisation and its effectiveness as a regulatory instrument in addressing the high trade margin issue and its effect on generic drug prices. The trade association representatives, in their submissions, highlighted the need for balancing the two aspects of affordability and availability of drugs in formulating any policy on trade margins. In view of the uniqueness of drugs as a product and the costs associated with its proper storage and transportation in compliance of the statutory provisions, they urge for floor rates for trade margins that make the business of stockists and chemists viable. It is pertinent to mention here that many respondents attributed the industry standard of 30% margin (wholesale and retail together) for non-scheduled drugs to an agreement/understanding between the AIOCD and the manufacturers’ associations, which dates back to 1982. Collective determination of trade margins by associations has been held to be anti-competitive by the Commission in the past. For instance, in the case of Varca Druggists and Chemists & Ors. v. Chemist & Druggist Association, Goa (CDAG),37 the Commission termed the imposition of guidelines by CDAG that laid down the margins for wholesalers and retailers as anti-competitive and against the interests of consumers. As part of these guidelines, CDAG had also prescribed a cap on the discount a wholesaler could give the retailer and prohibited the retailers from giving any discounts to consumers. CCI had directed CDAG to remove the clauses in the Circulars, MoU, and Guidelines and file an undertaking to this effect in its order.

57. On the issue of margin capping, the representatives of AIOCD welcomed the pilot exercise undertaken by the NPPA for select anti-cancer drugs. The representatives of a pharmaceutical manufacturers’ association shared their concerns, inter alia, with respect to the margin-capping formula used by NPPA. As per their submission, the PTS used for margin capping is not the actual PTS but a derived figure that is computed by dividing the sum of net sales realisation of the product by the manufacturer as the case may be for sales during June 2018 by the total quantity of product sold in June 2018. This, according to them, artificially deflates the price, as the quantity includes products that involved no trade channels and where no trade margins were paid i.e., free products under Patient Assistance Program (PAP) and Government Procurement through tender process. They mentioned that the actual PTS data is available with manufacturers, which is verifiable from government databases, for the calculation of retail prices under trade margin rationalisation. Sector experts who participated in the study pointed out certain limitations of margin rationalisation in bringing down drug prices, such as, i) substitution of drugs under margin control with those out of its ambit when all molecules in a therapeutic class are not covered under the rationalisation scheme, and ii) the likelihood of increase in the sale of higher-priced drugs owing to the retailers’ or hospitals’ interest in selling drugs which fetch them maximum financial incentive in absolute value.

ONLINE PHARMACIES

58. Digital technology has created new opportunities in the healthcare space. Digitalisation of healthcare infrastructure is expected to expand reach, improve effectiveness of delivery, and enhance supply chain efficiency. The retail pharmaceutical market is undergoing a palpable change with the entry of e-pharmacy.38 While the share of e-pharmacy in the overall pharmaceutical retail market is still miniscule, estimated at around 2.8% in 2018, its growth has been noteworthy. The pandemic has provided further impetus, with over 8.8 million households of around 300 million households having accessed the online pharmacy market during the COVID-19 lockdown period compared to 3.5 million in the pre-COVID-19 phase.39 This uptrend is likely to continue, given the huge untapped potential. As per RedSeer Consulting’s revised estimates, e-pharmacy in India will be able to tap ~70 million households by FY 2025.40 The e-pharmacy space in the country is also witnessing entry and consolidation via major mergers and acquisitions. For instance, e-commerce major Amazon has entered the segment this year, while Reliance Retail has acquired a majority stake in Netmeds, PharmEasy acquired Medlife41,42,43, and Tata Group acquired a 65% stake in 1mg.

59. E-pharmacy functions under two major models in India — inventory-based model and marketplace-based model, with some online pharmacies being run as part of larger multi-product e-commerce platforms. A significant part of online pharmacy business in India is conducted under the marketplace-based model, wherein online pharmacies play the role of an intermediary technology platform, connecting buyers and sellers. The aggregator links registered pharmacies for delivery of medicines to consumers, directly through licensed chemists. The inventory-based model is premised on the principle of ownership of inventory of medicines. Under this model, online pharmacies integrate their warehousing functions with carry and forwarding agents, who are the immediate front line for drug companies. The stocks that online pharma companies procure from manufacturers are delivered to consumers directly. The advantage of this model is a truncated supply chain with fewer intermediaries, allowing for higher margin and higher consumer discounts.

60. Online players are also driving offline pharmacies to an ‘omnichannel experience’ where they are offering doorstep delivery to customers. Omnichannel refers to an engagement that integrates various events and channels (offline and online model) relating to buying medicines by customers. A decentralised online model is also expanding quickly, where local offline pharmacies are simultaneously offering online services in an effort to retain and grow their customer base. Smaller online players, typically extensions of existing offline pharmacy shops, use an inventory-based model to directly connect with the customer through use of mobile applications or phone-delivery. These are hyper-local models with limited geographical coverage. Many Tier 2 and Tier 3 towns have seen a proliferation of these online pharmacies.

61. Stakeholder consultation with respect to online pharmacies focused, inter alia, on i) whether and how online distribution was impacting or was likely to impact the distribution landscape of drugs, hitherto predominantly operated through brick and mortar channels, ii) whether online pharmacies have stimulated competition in the retail market on price and non-price dimensions, and iii) what opportunities and challenges do online pharmacies face for emerging as a credible competitive force in the pharmaceutical retail market in India.