Mr. Shreshth Tayal, IRS (IT: 2018)

Assistant Commissioner of Income-Tax, Delhi

shreshth.tayal@incometax.gov.in

Mr. Shreshth Tayal is an Assistant Commissioner of Income Tax currently posted in New Delhi. He is a Chartered Accountant and Company Secretary by qualification. Before joining the IRS, he worked in the International Tax team of one of the Big Four tax consulting firms for three and a half years.

Executive Summary

This article introduces a fresh perspective to the taxation of offshore indirect transfer of immovable property. It argues that such offshore indirect transfer can be taxed under the specific anti-abuse provisions of Section 2(47)(vi) of the Income-tax Act 1961 as they stood prior to the retrospective amendments brought into the Act through the Finance Act 2012. The article further discusses the possible need to amend the Act to cover similar indirect transfer of movable property under Section 2(47) as well as the need to bring amendments to Article 13 of the Double Taxation Avoidance Agreements to cover indirect transfer of certain movable properties.

INTRODUCTION

The applicability of Capital Gains on Indirect Transfer arrangements made headlines in 2012 after the landmark ruling of the Hon’ble Supreme Court in the Vodafone case1 and the consequent clarificatory retrospective amendments brought out in the Income-tax Act 1961 (‘Act’) through the Finance Act 2012. The Indirect Transfer provisions have since been discussed and deliberated upon extensively both domestically and internationally.

However, there is a particular provision in the Income-tax Act which deals with indirect transfer of immovable property which, in the opinion of the author, has not been studied adequately in the tax literature. Clause (47) of Section 2 of the Act deals with the definition of ‘transfer’ in relation to a capital asset. As per Sub-clause (vi) of Section 2(47), any transaction which has the effect of transferring, or enabling the enjoyment of, any immovable property is covered in the definition of ‘transfer’. This paper aims to discuss the applicability of this provision in case of indirect transfer of immovable property, especially in case of non-residents; the possible need for expansion of the existing provisions in the Act; and the corresponding provisions on indirect transfer of immovable and movable properties in the tax treaties.

SECTION 2(47)(VI)

The relevant extracts of Section 2 are produced below for ready reference:

Definitions

2. In this Act, unless the context otherwise requires,-

(47) ‘transfer’, in relation to a capital asset, includes, –

(vi) any transaction (whether by way of becoming a member of, or acquiring shares in, a co-operative society, company or other association of persons or by way of any agreement or any arrangement or in any other manner whatsoever) which has the effect of transferring, or enabling the enjoyment of, any immovable property.

Explanation 1.—For the purposes of Sub-clauses (v) and (vi), ‘immovable property’ shall have the same meaning as in Clause (d) of Section 269UA.’

Sub-clause (vi) was inserted in Section 2(47) vide Finance Act 1987 with effect from AY 1988-89. This provision specifically brings into the ambit of the term ‘transfer’ any transaction by way of any agreement, or arrangement, or in any other manner which has the effect of transferring, or enabling the enjoyment of, any immovable property. The term ‘immovable property’ has been defined in Clause (d) of Section 269UA as under:

‘(d) ‘immovable property’ means –

(iv) any land or any building or part of a building, and includes, where any land or any building or part of a building is to be transferred together with any machinery, plant, furniture, fittings or other things, such machinery, plant, furniture, fittings or other things also.

Explanation — For the purposes of this sub-clause, ‘land, building, part of a building, machinery, plant, furniture, fittings and other things’ include any rights therein;

(ii) any rights in or with respect to any land or any building or a part of a building (whether or not including any machinery, plant, furniture, fittings or other things therein) which has been constructed or which is to be constructed, accruing or arising from any transaction (whether by way of becoming a member of, or acquiring shares in, a co-operative society, company or other association of persons or by way of any agreement or any arrangement of whatever nature), not being a transaction by way of sale, exchange or lease of such land, building or part of a building;’

[Emphasis supplied]

Therefore, the term ‘immovable property’ is defined in a very wide manner and is harmonious to the definition of ‘transfer’ given in Section 2(47).

SCOPE OF TAXATION IN CASE OF NON-RESIDENTS

The scope of taxation in case of Non-Residents is provided for by Section 5 of the Act. The relevant portion of Section 5 is produced below:

Scope of Total Income

5. (1) …….

(2) Subject to the provisions of this Act, the total income of any previous year of a person who is a non-resident includes all income from whatever source derived which—

(a) is received or is deemed to be received in India in such year by or on behalf of such person; or

(b) accrues or arises or is deemed to accrue or arise to him in India during such year.’

In other words, any income which is received or is deemed to be received in India or which accrues or arises or is deemed to accrue or arise in India to a non-resident is taxable in his hands in India during the relevant previous year. What constitutes income that is deemed to accrue or arise in India is provided for in Section 9 of the Act. The portion of Section 9 that is relevant for the topic under discussion is given below:

‘Income deemed to accrue or arise in India.

9. (1) The following incomes shall be deemed to accrue or arise in India:

(i) all income accruing or arising, whether directly or indirectly, through or from any business connection in India, or through or from any property in India, or through or from any asset or source of income in India, or through the transfer of a capital asset situate in India.’

[Emphasis supplied]

Section 9(1)(i) provides that any income accruing or arising, whether directly or indirectly, through the transfer of a capital asset situated in India shall be deemed to accrue in India. Therefore, the provision provides for source based taxation of capital gains arising from the transfer of capital assets situated in India.

INDIRECT TRANSFER OF IMMOVABLE PROPERTY SITUATED IN INDIA

The indirect transfer of immovable property has always been a contentious issue in taxation, internationally. There are divergent provisions to tax indirect transfers of immovable property in the domestic laws of different countries. Even in the tax treaties, the provision for taxation of transfer of immovable property through offshore indirect transfers is found only in around 35% of all Double Taxation Avoidance Agreements (‘DTAA’) globally.2

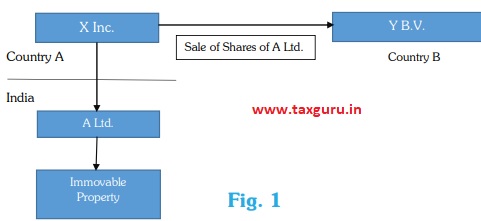

Before proceeding further, we need to understand the meaning of the term ‘indirect transfer of immovable property’. Suppose, a person (X Inc.), resident of Country A holds certain immovable property in India which it desires to sell to another non-resident company in Country B (Y B.V.). If X Inc. directly sells its immovable property in India, the capital gains arising on such transfer shall be deemed to accrue or arise in India by virtue of applicability of Section 9(1)(i) quoted above.

In order to avoid the above tax liability in India, X Inc. may opt to hold the immovable property in India through a subsidiary entity and sell the shares or interest in that entity to Y B.V. Two cases may arise in such indirect transfers which are discussed below.

In the case described above, X Inc. sells the shares of its subsidiary in India, A Ltd., which in turn holds the immovable property in India. The immovable property is sold to Y B.V. indirectly through the shares of A Ltd. However, this arrangement may not succeed in avoiding tax liability as the shares of A Ltd. constitute a capital asset situated in India and the capital gains arising to X Inc. on sale of such shares is deemed to accrue or arise in India under the domestic provisions. Such a transaction will also be taxed in India under Article 13(5) of most of the Indian DTAAs.

A different tax planning would be to hold the rights in the immovable property in India through a subsidiary entity located in a low or no tax jurisdiction. The scenario is described below.

In the above case, X Inc. sells shares of A Ltd. to Y B.V. which, in effect, transfers the immovable property in India to Y B.V. This is a classic example of an offshore indirect transfer of immovable property in India. This case will be examined in extensive detail in the paragraphs below.

Taxation of Offshore Indirect

Transfers of Immovable Property under the Income–tax Act 1961

Sometimes, it is alleged that the provisions to tax offshore indirect transfers were brought into the Act for the first time only in 2012, vide the retrospective amendments brought in by the Finance Act 2012, through the insertion of Explanation 5 to Section 9(1)(i) and other corresponding amendments.3 However, the indirect transfer of immovable property as described in the aforesaid cases has always been covered under the ambit of the Income-tax Act, 1961 since AY 1988-89. This is where Section 9(1)(i) read with Section 2(47)(vi) comes into play.

As discussed above, Section 9(1)(i) deems any income accruing or arising, directly or indirectly, through the transfer of a capital asset situated in India as income accruing or arising in India. Therefore, for income to be deemed to accrue or arise in India, the following conditions need to be satisfied:

1. There should be a ‘transfer’.

2. The transfer should be of a capital asset.

3. The capital asset should be situated in India.

All the above conditions are satisfied in the offshore indirect transfer case described above. The term ‘capital asset’ is defined under Section 2(14) in a very wide manner and the immovable property in India that has been transferred in the aforesaid case qualifies as a capital asset under Section 2(14)4. Since the immovable property is located in India, it qualifies the third condition of capital asset being situated in India.

With regards to transfer of the capital asset in question through the shares of company located in Country C (A Ltd.), it qualifies as ‘transfer’ by virtue of Section 2(47)(vi) which includes in the definition of ‘transfer’ any transaction by way of acquiring shares in a company or by way of any agreement or any arrangement or in any other manner whatsoever, which has the effect of transferring or enabling the enjoyment of, any immovable property. Since the immovable property in India gets transferred to the company in Country B (Y B.V.) by virtue of acquiring shares of A Ltd., the said arrangement qualifies the definition of transfer as given in Section 2(47)(vi).

In view of the above, India has the authority to tax such offshore indirect transfers of immovable property by virtue of Section 9(1)(i) read with Section 2(47)(vi).

The various arguments that can be raised against the above taxability of the offshore indirect transfer of immovable property have been discussed and dealt with in the subsequent paragraphs.

1. The Capital Asset being transferred in the above transaction are the shares of A Ltd. and such shares are not situated in India

It may be argued by the taxpayers that what is being transferred in the given transaction are the shares of A Ltd. and not the immovable property located in India. Therefore, the capital asset in question is not situated in India and the transaction does not qualify the third condition specified above for applicability of Section 9(1)(i).

However, it seems that this argument will not stand the test of judicial scrutiny. Section 2(47) (vi) is a specific anti-abuse rule against such very transactions that involve the transfer or enjoyment of immovable property by way of acquiring shares in a company or becoming a member of a cooperative society or any other agreement or arrangement. Section 2(47) (vi) specifically provides for a ‘look through’ approach and allows for taxation of transfer of an immovable property done by means of arrangements mentioned above. Section 2(47) (vi) has been worded in a very wide manner. This can be seen from the use of the expressions ‘any transaction (whether by way of becoming a member of, or acquiring shares in, a co-operative society, company or other association of persons or by way of any agreement or any arrangement or in any other manner whatsoever) which has the effect of transferring, or enabling the enjoyment of, any immovable property.’ In other words, any agreement or an arrangement which has the effect of transferring an immovable property in India qualifies the definition of ‘transfer’ and therefore qualifies as income deemed to accrue or arise in India in the hands of the non-resident under Section 9(1)(i).

2. The Intention of Introducing Sub-clause (vi) to Section 2(47) was Very Narrow

It may be argued by the taxpayers that the application of Section 2(47)(vi) to indirect transfer of immovable property may be not be permissible within the scope of the provisions of the section and that the intention of the provision was never to bring indirect transfers into the tax net. The scope and intention of Sub-clause (vi) can be understood from the CBDT Circular No. 495 dated September 22, 1987. The relevant portion of the Circular is produced below:

‘Definition of “transfer” widened to include certain transactions

11.1 The existing definition of the word ‘transfer’ in Section 2(47) does not include transfer of certain rights accruing to a purchaser, by way of becoming a member of or acquiring shares in a co-operative society, company, or association of persons or by way of any agreement or any arrangement whereby such person acquires any right in any building which is either being constructed or which is to be constructed. Transactions of the nature referred to above are not required to be registered under the Registration Act, 1908. Such arrangements confer the privileges of ownership without transfer of title in the building and are a common mode of acquiring flats particularly in multistoreyed constructions in big cities. The definition also does not cover cases where possession is allowed to be taken or retained in part performance of a contract, of the nature referred to in Section 53A of the Transfer of Property Act 1882. New Sub-clauses (v) and (vi) have been inserted in Section 2(47) to prevent avoidance of capital gains liability by recourse to transfer of rights in the manner referred to above.

11.2 The newly inserted Sub-clause (vi) of Section 2(47) has brought into the ambit of ‘transfer’, the practice of enjoyment of property rights through what is commonly known as Power of Attorney arrangements. The practice in such cases is adopted normally where transfer of ownership is legally not permitted. A person holding the power of attorney is authorised the powers of owner, including that of making construction. The legal ownership in such cases continues to be with the transferor.

11.3 These amendments shall come into force with effect from 01.04.1988 and will accordingly apply to the assessment year 1988-89 and subsequent years.

[Section 3(g) of the Finance Act]”

[Emphasis supplied]

It may be argued that the intention of introducing Sub-clause (vi) is clearly provided in the above Circular which aims at covering transactions (like flats in building by co-operative societies or enjoyment of property through power of attorney arrangements) which were otherwise not covered in the ambit of the term ‘transfer’. The Memorandum explaining the Finance Bill, 1987 also uses similar language. The situation of an indirect transfer of immovable property through shares of a foreign company was not envisaged while introducing Sub-clause (vi) in the Act.

Even if it is accepted that the intention of introducing Sub-clause (vi) to Section 2(47) was only to deal with situations mentioned in the Circular above, that does not restrict the quasi-judicial powers of the tax authorities to deal with transfer of immovable property through arrangements that are covered by the express language of the provisions of Section 2(47)(vi). Recourse to the Memorandum explaining the Finance Bill and the departmental circular needs to be taken only when there is any ambiguity regarding the interpretation of any statutory provision. Where a particular transaction is clearly covered by the wordings of a provision, the intention behind introducing the particular provision need not be ascertained.

Reliance in this regard can be placed on the cardinal rule of interpretation of statute, i.e. the literal rule of interpretation. It is a settled principle that it is when the language is vague that the Legislature’s intention is to be taken into consideration. The Hon’ble Supreme Court in the case of Pandian Chemicals Ltd.5 while interpreting the provisions of Section 80HH of the Act, observed as under:

‘8. The learned counsel for the appellant then contended that having regard to the object with which Section 80HH was introduced in the statute book, this Court should give a liberal interpretation to the words in a manner so as to allow such object to be fulfilled. The rules of interpretation would come into play only if there is any doubt with regard to the express language used. Where the words are unequivocal, there is no scope for importing any rule of interpretation as submitted by the appellant.’

[Emphasis supplied]

Further reliance can be placed on the decision of the Hon’ble Apex Court in the case of Bhaiji vs. Sub-Divisional Officer, Thandla6 where the Court was dealing with the amendments brought out in the M.P. Land Revenue Code 1959. The Court observed as under:

‘Reference to the Statement of Objects and Reasons is permissible for understanding the background, the antecedent state of affairs, the surrounding circumstances in relation to the statute, and the evil which the statute sought to remedy. The weight of judicial authority leans in favour of the view that Statement of Objects and Reasons cannot be utilized for the purpose of restricting and controlling the plain meaning of the language employed by the Legislature in drafting statute and excluding from its operation such transactions which it plainly covers. (See Principles of Statutory Interpretation by Justice G.P. Singh, Eighth Edition 2001, pp.206-209).’

[Emphasis supplied]

Thus, it can be said that the Memorandum and the Circular only describe the loopholes at that point of time which were being fixed by introducing this provision. Nowhere does it stop the tax authorities from applying the provision to other situations where it can be applied. The Legislature cannot be expected to foresee all possible situations where there may be transfer of immovable property indirectly and mention them in the Memorandum. By wording the provision in the widest manner possible, the Legislature has expressed its intent to tax all agreements or arrangements which have the effect of transfer of immovable property in India.

3. Application of Section 2(47)(vi) to indirect transfer of immovable property is akin to lifting of corporate veil in all cases

It may be argued on behalf of the taxpayers that the use of Section 2(47)(vi) read with Section 9(1)(i) to tax indirect transfer of immovable property in India would mean that the corporate veil of the intermediary company is being lifted in all cases. The corporate veil of an entity should be lifted only when it is specifically provided for by the Statute itself or where, due to glaring facts established on record, it is found that a complex web has been created only with a view to defraud the revenue interest of the State. Further, there are no safeguards that have been provided in Section 2(47)(vi) as have been provided in Explanation 6 to Section 9(1) in case of transfer of shares or interest in a company or entity registered or incorporated outside India. Explanation 6 provides that value of the assets located in India should exceed the amount of ten crore rupees and they should represent at least 50 per cent of the value of all the assets owned by the company or entity.

At the cost of repetition, it is imperative to mention that Section 2(47)(vi) is a specific anti-abuse rule that aims to tax capital gains arising from transfer of immovable property situated in India. The provision clearly enables the tax authorities to lift the corporate veil of the intermediary companies to tax the gains arising from transfer of immovable property located in India. The provision is similar to Article 13(4) of the Model Tax Conventions issued by OECD and UN which provide that gains derived by a resident of one Contracting State from the alienation of shares or comparable interests may be taxed in the other Contracting State if, at any time during the 365 days preceding the alienation, these shares or comparable interests derived more than 50 per cent of their value directly or indirectly from immovable property, situated in the other State.7 While the Model Conventions provide for a 50 per cent condition in determining the taxability of the transfer of the shares or interests in the country where the immovable property is located, the domestic law of India provides for such taxation in India in all cases, irrespective of the proportion the value of the immovable property bears to the total value of the shares being transferred. India believes that there should be no difference in the taxation on transfer of immovable property if it is done directly (taxed fully in India) or if it is done indirectly, even if such property accounts for say just 30% of the value of the shares of the foreign company. The proportionate gain arising from such transfer should be taxed in India by virtue of the source (to the extent of the immovable property) being situated in India. What is being taxed is the transfer of the immovable property situated in India by whatever agreement or arrangement.

This can be explained with the help of an illustration. Suppose the entire shares of F Co. are sold outside India for a value of Rs. 300 Crores, of which a proportion in value (say 30%) is derived from the immovable property located in India, then the gain arising on the transfer value (Rs. 90 Crores) of the immovable property located in India shall be taxable in India under the provisions of Section 9(1)(i) read with Section 2(47)(vi).

Therefore, in view of the above discussion it can be said that Section 2(47)(vi) is a very relevant provision in the taxation of non-residents and an offshore indirect transfer of immovable property in India can be brought to tax in India by virtue of Section 9(1)(i) read with Section 2(47)(vi).

APPLICABILITY OF SECTION 2(47)(VI) TO THE CAIRN TAX DISPUTE

At this juncture, it may be relevant to refer to the case of Cairn UK Holdings Ltd.8 wherein a UK company (CUHL) sold the entire shareholding of its subsidiary company in Jersey (CIHL) to an Indian Company (CIL). The shares of the Jersey Company (CIHL) derived their value from India since CIHL was the holding company of 9 subsidiary companies in India which were engaged in the business of oil and gas sector in India. The Ld. Assessing Officer taxed such transfer in the hands of CUHL in India after applying Section 9(1)(i) read with Explanation

5. The Hon’ble Delhi ITAT decided the case in favour of the Department9,10.

From the provisions and the facts of the case, it appears that the provisions of Section 2(47)(vi) also seem to be applicable in the instant case. CUHL indirectly held various oil and gas blocks in India through its Indian subsidiaries and these subsidiaries where indirectly transferred to CIL through the transfer of the entire shareholding of CIHL. The essence of the arrangement was to transfer the immovable property in India (oil and gas blocks) to CIL through the transfer of shares of CIHL. It is a classic case of indirect transfer of immovable property in India and should be covered by the provisions of Section 2(47)(vi).11

The assessee in the Cairn case had also challenged legal validity of the retrospective application of Explanation 5 to Section 9(1)(i) before the Hon’ble ITAT. The ITAT has held that it is not the appropriate forum to rule on the constitutional validity of the retrospective application of the indirect tax provisions. However, the Hon’ble ITAT, by holding that the assessee cannot be burdened with the levy of interest where it could not have visualized its tax liability at the time of the transaction, has tacitly lent credence to the view that the indirect transfer provisions were a new levy which had not existed previously. It seems that this contention could not have been raised by the assessee against the applicability of Section 2(47)(vi) to tax the indirect transfer of immovable property in the case. The indirect transfer of immovable property in India is taxable in India since the introduction of Section 2(47) thereby making Cairn liable to tax in India with applicable interest.

NEED FOR EXPANSION OF THE PROVISIONS OF SECTION 2(47)(VI)

While the indirect transfer of immovable property in India is taxable under the provisions of Section 9(1)(i) read with Section 2(47)(vi) as discussed above, there seems to be no parallel provision in the Act for the taxation of indirect transfer of movable property situated in India. The only provision that attempts to tax such indirect transfers is given in Explanation 5 to Section 9(1)(i), which was introduced through the Finance Act 2012. The Explanation is produced below for ready reference:

“Explanation 5 – For the removal of doubts, it is hereby clarified that an asset or a capital asset being any share or interest in a company or entity registered or incorporated outside India shall be deemed to be and shall always be deemed to have been situated in India, if the share or interest derives, directly or indirectly, its value substantially from the assets located in India:”

In simple words, the Explanation provides that the shares of a foreign company shall be deemed to be a capital asset situated in India if they derive their value substantially from the assets located in India. The income from the transfer of such a capital asset in India shall be deemed to accrue or arise in India under the provisions of Section 9(1)(i). Thus, the Explanation explicitly taxes the indirect transfer of assets located in India through the transfer of shares of a foreign company. The procedural aspects for the taxation of such indirect transfers are provided in Explanation 6, Explanation 7 and the provisos to Explanation 5 to Section 9(1)(i).

We know that the taxability of a non-resident is governed by the provisions of the domestic law as well as the provisions of the applicable Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement (‘DTAA’). By virtue of Section 90(2), the provisions of the Act or the DTAA, whichever are more beneficial to the assessee are applicable to a non-resident in India. The provisions of the DTAA which are relevant to the discussion in this paper are given in paras 4 and 5 of Article 13 (Capital Gains) of the UN Model Convention. The provisions are produced below for ready reference:

‘4. Gains derived by a resident of a Contracting State from the alienation of shares or comparable interests, such as interests in a partnership or trust, may be taxed in the other Contracting State if, at any time during the 365 days preceding the alienation, these shares or comparable interests derived more than 50 per cent of their value directly or indirectly from immovable property, as defined in Article 6, situated in that other State.

5. Gains, other than those to which paragraph 4 applies, derived by a resident of a Contracting State from the alienation of shares of a company, or comparable interests, such as interests in a partnership or trust, which is a resident of the other Contracting State, may be taxed in that other State if the alienator, at any time during the 365 days preceding such alienation, held directly or indirectly at least—per cent (the percentage is to be established through bilateral negotiations) of the capital of that company.’

Since Article 13(4) deals with the indirect transfer of immovable property, it seems to be more or less similar to the domestic law provisions given in Section 9(1)(i) read with Section 2(47)(vi) discussed in the preceding paragraphs. On the other hand, Article 13(5) only deals with a situation where the shares of a company located in a Contracting State (say, India) are transferred by a person from another Contracting State (say, UK). It does not deal with a situation where the UK resident sells the assets located in India indirectly through the shares of a foreign company (say, a company located in France which derives its value substantially from the assets located in India). Therefore, it can be seen that there is no parallel provision to Explanation 5 of Section 9(1)(i) in the DTAAs to tax indirect transfer of property in India (except to the extent of immovable property covered by Article 13(4)). Such a situation makes the provisions of Explanation 5 otiose in many cases as the taxpayer is governed by the beneficial provisions under the applicable DTAA.

Further, Section 9(1)(i) read with Explanation 5 deems the shares of the foreign company to be a capital asset situated in India and requires the gains from the transfer of such shares to be taxed in proportion to the value attributable to the assets located in India. As the high number of litigations and the frequent amendments to the provisions show, the application of these provisions has proved to be cumbersome and contentious.

From the above discussion, it appears that the complexities involved in the taxation of indirect transfers may be avoided if, instead of deeming the shares of the foreign company to be a capital asset situated in India (as has been done by Explanation 5 to Section 9(1)(i)), there is a provision which directly considers such indirect transfers of the assets located in India to be a ‘transfer’ of a capital asset situated in India. This objective can be achieved by either expanding the existing provisions of Section 2(47)(vi) to cover transfer of movable property as well or by inserting a new Sub-clause (vii) to Section 2(47) for indirect transfer of movable property and is worded on the same lines as Sub-clause (vi) on immovable property.

Such a combined applicability of Sub-clauses and (vii) to Section 2(47) would lead to the taxation of the indirect transfer of any capital asset located in India (movable or immovable) through the transfer of shares or interests in a company or entity registered or incorporated outside India or through any agreement or arrangement or in any other manner whatsoever.

In this regard, it is also imperative to mention that there will be a need to prescribe clarity on the computation mechanism for the capital gain computation for such indirect transfer and also bring clarity on the interplay of the amended provisions with the existing indirect transfer provisions in Explanation 5, 6 and 7 to Section 9(1)(i). However, in the opinion of the author, such an introduction of Sub-clause to Section 2(47) would make the taxation of indirect transfer of capital assets situated in India simpler and less litigative.

NEED FOR AMENDMENTS IN THE TREATY PROVISIONS

As has been stated above, the taxation of a non-resident is determined by the domestic law provisions as well as the provisions of the applicable DTAA. Article 13(4) (identical in the 2017 updates of the UN and the OECD Model Conventions) deals with the indirect transfer of immovable property and grants the Source State the right to tax such capital gains in case the shares of the foreign company derive more than 50 per cent of their value from immovable property located in the Source State.

On the other hand, Article 13(5) of the UN Model Convention taxes the gains from the alienation of the shares of a company or comparable interests (say, located in India) in the Source State (India) if the alienator (say, in UK) holds directly or indirectly a specified percentage of the capital of the company. Such a provision is absent in the OECD Model Convention.

Article 13(6) of the UN Model Convention (and Article 13(5) of the OECD Model Convention) provide for a residuary clause which states that gains derived from alienation of property not covered by any of the preceding paragraphs of Article 13 are taxable in the State where the alienator is resident. Therefore, residence based taxation is applied under this paragraph.

From the combined reading of all the above provisions, it can be seen that in the case of immovable property located in the Source State, while the direct transfer is taxed in the Source State under Article 13(1), the indirect transfer is taxed in the Source State under Article 13(4), provided the prescribed conditions are met. However, there are no such similar provisions to tax the indirect transfer of movable properties referred to in Article 13(5) of the UN Model (i.e. shares or comparable interests in an entity located in the Source State) where the direct transfer of the same properties is taxable in the Source State under paragraph 5 of Article 13. The indirect transfers of such shares or comparable interests are covered by the residuary clause under Article 13(6) giving the entire taxing rights to the Residence State.

To elucidate this point in detail, let us take the following example. A Ltd. (resident in Belgium) holds 30% shares in B Ltd. (resident in India). As per Article 13(5) of the India-Belgium treaty, the gains from the sale of shares of B Ltd. by A Ltd. shall be taxable in the Source State (India) since A Ltd. holds at least 10% in the capital stock of B Ltd. Therefore, Article 13(5) provides for source based taxation in case of such direct transfers of movable property in the nature of shares. However, in case A Ltd. resorts to indirect transfer of such shares through an intermediary (say, a subsidiary C Ltd. in Mauritius which holds these 30% shares in B Ltd.), such transfer would be outside the ambit of Article 13(5) preventing India to tax such gains.

It is a widely accepted fact that income should be taxed in the jurisdiction where the economic value is created. When the impact of a direct as well as an indirect transfer is the same, there should be no difference in the taxing rights of such transfers. There needs to be tax neutrality between direct and indirect transfer of assets. Keeping this in mind, there may be a need to introduce adequate provisions in the Model Conventions to provide the taxing rights over such indirect transfers of movable property (in the nature of shares or comparable interests) to the Source State bringing them in line with the taxing rights over the direct transfer of these assets. This will prevent any abusive transactions that may be undertaken to avoid tax under Article 13(5). Such a provision can be introduced by appropriately amending the provisions of Article 13(5) or by expanding the provisions of Article 13(4) to cover the movable properties mentioned in Article 13(5).

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, it can be said that Section 2(47) is a very wide and powerful section that can be effectively applied to tax the indirect transfer of immovable properties situated in India. It effectively provides for the ‘look through’ approach in such indirect transfers and can be applied without taking assistance of any of the retrospective amendments brought in by the Finance Act 2012.

As discussed in the preceding paragraphs, there may be a need to expand the provisions of Section 2(47)(vi) to cover such indirect transfers of movable properties as well, to enable the taxman to prevent abuse of indirect transfer arrangements in a simple and unambiguous manner. Further, India needs to continue to strive to amend the provisions of Article 13 (Capital Gains) in the Model Conventions to provide for taxing rights to the Source State in the case of indirect transfers of movable properties that are in the nature of shares or comparable interests.

Notes:-

1Vodafone International Holdings B.V. vs. Union of India (341 ITR 1) (SC)

2Draft Version 2 of The Taxation of Offshore Indirect Transfers–A Toolkit by the Platform for Collaboration on Tax.

3The scope of Explanation 5 is discussed later in this paper.

4However, the immovable property in question should not be a rural agricultural land.

5Pandian Chemicals Ltd. vs. CIT [2003] 129 Taxman 539 (SC)

6Bhaiji vs. Sub-Divisional Officer, Thandla 2003(1) SCC 692

7Article 13(4) of the Model Conventions is discussed in greater detail later in this paper

8Cairn UK Holdings Ltd. vs. DCIT [2017] 185 TTJ 593 (Delhi – Trib.)

9The Court however ruled against the Department on the issue of levy of interest under Sections 234A and 234B

10The case was challenged for international arbitration by Cairn under the UK-India Bilateral Investment Treaty. While the main court hearings were completed in the case in August 2018, the arbitral award is expected to be issued not before mid-2020 as per the latest updates. However, the arbitral award will have no bearing on the sovereign right of India to tax income sourced in India. The arbitration has been undertaken under the Bilateral Investment Treaty and not under any tax treaty.

11The issue regarding whether oil and gas blocks constitute ‘immovable property’ in India has not been dealt with in this paper and for the sake of brevity, it has been assumed that extraction in the oil and gas blocks will be covered by the term ‘any rights therein’ used in the definition of ‘immovable property’ in Section 269UA.

Source- Taxalogue 3- April to June 2020