The Convergence of Corporate Compliance and Fiscal Statute: A Comprehensive Analysis of Director Loans under the Companies Act, 2013 and the Income Tax Act, 1961

Executive Summary

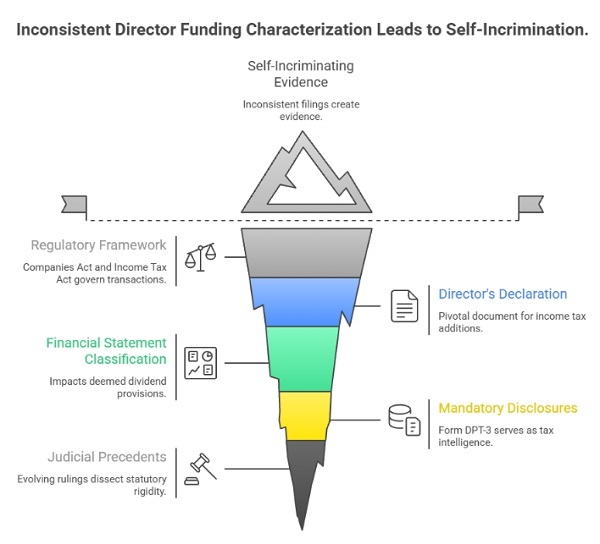

This Article proposes a Unified Compliance Theory, arguing that inconsistent characterisation of director funding across MCA filings, financial statements, and income-tax proceedings creates self-incriminating evidence. The solution lies in harmonised documentation, banking-channel discipline, and pre-acceptance creditworthiness vetting

The financial relationship between a director and their company represents one of the most complex intersections of corporate governance and fiscal administration in India. For closely held private limited companies, funds introduced by directors often serve as the immediate lifeblood of operations, bridging cash flow gaps and facilitating capital requirements without the procedural rigidities of external debt financing. However, this financial fluidity operates within a rigorous regulatory framework: the Companies Act, 2013, which regulates the authorization and nature of such transactions to protect stakeholders, and the Income Tax Act, 1961, which monitors these transactions to prevent the laundering of unaccounted wealth and the generation of black money.

This report provides an exhaustive analysis of the interplay between these two statutes. While previous analyses may have focused on the penal provisions of Section 269SS of the Income Tax Act in isolation, this document expands the horizon to the critical intersection where corporate law definitions determine tax liabilities. It explores how a “Director’s Declaration” under Rule 2(1)(c)(viii) of the Companies (Acceptance of Deposits) Rules, 2014, serves as a pivotal evidentiary document for additions under Section 68 of the Income Tax Act; how the classification of “Current Accounts” in financial statements impacts the applicability of Deemed Dividend provisions under Section 2(22)(e); and how the mandatory disclosures in Form DPT-3 serve as an intelligence mine for tax authorities.

The analysis is anchored in statutory provisions, evolving judicial precedents such as CIT v. Idhayam Publications, CIT v. Tarulata Shyam, and recent tribunal rulings like Thamira Green Farms, dissecting the friction between the commercial necessity of “survival funds” and the statutory rigidity of “loans and deposits.”

Chapter 1: The Statutory Architecture of Director Financing

To navigate the complex interplay between the Companies, Act and the Income Tax Act, one must first deconstruct the individual statutory frameworks that govern director loans. The treatment of a simple cash infusion differs radically depending on the lens through which it is viewed—whether as a “Deposit” under corporate law, a “Loan” under tax law, or a “Current Account” under commercial practice.

1.1 The Companies Act, 2013: Restriction and Regulation

The Companies Act, 2013 (hereinafter “the 2013 Act”) marked a paradigm shift from the 1956 regime, introducing stringent controls on insider lending to ensure that corporate funds are not siphoned off for personal benefit and that companies do not act as unregulated deposit-taking schemes.

1.1.1 Section 73 and The Definition of “Deposit”

The core regulation for loans received by a company lies in Sections 73 to 76 read with the Companies (Acceptance of Deposits) Rules, 2014. The Act defines “Deposit” broadly under Section 2(31) to include any receipt of money by way of deposit or loan or in any other form. If a receipt is classified as a “Deposit,” the company must comply with onerous conditions: creating a deposit repayment reserve, obtaining credit ratings, and issuing circulars. For a private limited company, complying with these public deposit norms is often impossible or impractical for routine funding from directors.

The “Exempt Deposit” Mechanism:

To facilitate internal funding, Rule 2(1)(c)(viii) of the Deposit Rules provides a critical exemption. Any amount received from a person who, at the time of the receipt of the amount, was a director of the company is not considered a deposit. This exclusion is vital for private companies as it removes the transaction from the purview of the strict deposit regulations.

The Condition Precedent: The “Owned Funds” Declaration

This exemption is not absolute. It is conditional upon the director furnishing a declaration in writing to the effect that the amount is not being given out of funds acquired by him by borrowing or accepting loans or deposits from others. This “Owned Funds” declaration is the fulcrum of the interplay with the Income Tax Act. It forces the director to certify the source of funds, creating a direct evidentiary link to their personal financial standing.

1.1.2 Section 185: The General Prohibition on Outbound Loans

While the user’s primary concern involves loans from directors, the interplay is incomplete without understanding Section 185, which governs loans to directors. Section 185 posits a general prohibition: “No company shall, directly or indirectly, advance any loan… to any of its directors”.

The 2017 amendments introduced crucial carve-outs:

1. Managing/Whole-time Directors:Loans are permitted if they form part of a service condition extended to all employees or are approved by a special resolution.

2. Special Resolution Route (Section 185(2)):A company may advance a loan to any person in whom a director is interested (e.g., a private company where the director is a member) provided a special resolution is passed and the funds are utilized for the principal business activities of the borrower.

1.2 The Income Tax Act, 1961: The Anti-Evasion Shield

While the Companies Act focuses on governance and stakeholder protection, the Income Tax Act (ITA) focuses on the source and mode of funds to prevent tax evasion and the circulation of black money.

1.2.1 Section 269SS: The Mode of Acceptance

Section 269SS prohibits any person from taking or accepting any loan or deposit or “specified sum” otherwise than by an account payee cheque, bank draft, or electronic clearing system, if the amount exceeds ₹20,000.

- Penalty: 100% of the loan amount under Section 271D.

- Definition: “Loan or deposit” means loan or deposit of money. The circularity of this definition allows courts to interpret the character of the transaction. A crucial line of defense, established in CIT v. Idhayam Publications Ltd., argues that current account transactions between a director and a company do not fit the definition of a “loan” or “deposit” intended by the legislature, particularly when funds are introduced for immediate business exigencies.

1.2.2 Section 269T: The Mode of Repayment

Mirroring Section 269SS, Section 269T mandates that repayment of any loan or deposit exceeding ₹20,000 must also be via banking channels.

- Penalty:100% of the repaid amount under Section 271E.

- Journal Entries:A critical area of conflict is whether squaring off a loan via journal entries constitutes a violation. While the Bombay High Court has taken a view that journal entries might violate the spirit of the section in certain contexts, other appellate authorities have distinguished genuine book adjustments from cash transactions.

1.2.3 Section 68: Unexplained Cash Credits

This is the most potent weapon in the tax authority’s arsenal. Where any sum is found credited in the books of an assessee, and the assessee offers no explanation about the nature and source thereof, or the explanation is not satisfactory, the sum is charged to income tax.

- The Three Ingredients: Identity, Creditworthiness, and Genuineness.

- The “Source of Source” (Finance Act 2022):The amendment to Section 68 explicitly requires that for loans and borrowings, the explanation is deemed unsatisfactory unless the person who lent the money (the director) also offers an explanation about the nature and source of the sum so credited. This directly links the company’s tax liability to the director’s personal financial history.

Chapter 2: The “Deposit” Dilemma – Interplay of Definitions and Classifications

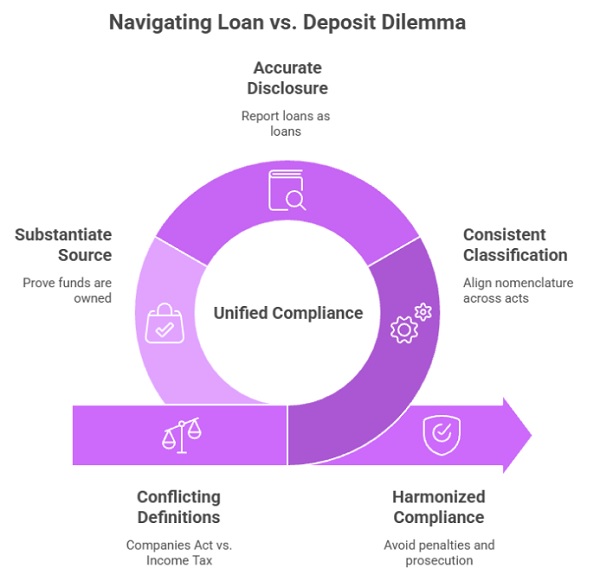

The first point of friction between the two Acts is the categorization of the transaction. Is it a “Loan,” a “Deposit,” or a “Current Account”? The nomenclature used in Companies Act compliance can have unintended and severe consequences in Income Tax proceedings.

2.1 The “Exempt Deposit” vs. “Loan” Paradox

Under the Companies Act, a receipt from a director is technically an “exempt deposit” if the declaration under Rule 2(1)(c)(viii) is furnished. It is not a deposit for the purpose of Chapter V of the Companies Act.

However, for the Income Tax Act, the definition of “loan or deposit” in the Explanation to Section 269SS is wider. It includes “loan or deposit of money.”

The Conflict:

Companies often argue before tax authorities that funds received from directors are “Current Account” transactions or “survival funds” and thus not “loans” or “deposits” to avoid Section 269SS penalties (relying on Idhayam Publications).

However, to satisfy the Registrar of Companies (RoC), the same company must classify these funds. If they are not “Deposits” (because private companies are generally prohibited from accepting deposits from the public), they must be classified as “Exempt Deposits” (i.e., Loans from Directors) in statutory filings like Form DPT-3.

The Interplay Insight:

If a company classifies a transaction as an “Exempt Deposit” (Loan from Director) in its Form DPT-3 filing to comply with the Companies Act, it effectively admits that the transaction is a “Loan.” This admission can be used by the Income Tax Department to rebut the argument that the transaction is merely a “Current Account” or “Trade Advance.”

- Evidentiary Value: The Idhayam Publications defense relies on the “nature” of the account being fluid and non-commercial. But Form DPT-3 requires categorical disclosure of “Loans from Directors.” An Assessing Officer (AO) can subpoena the DPT-3 filing to establish that the company itself treats the amount as a loan, thereby attracting Section 269SS.

2.2 The “Director’s Declaration” (Rule 2(1)(c)(viii)) as a Tax Trap

The Companies Act mandates that for a director’s loan to be exempt, the director must declare that the funds are “not borrowed”. This is a binary condition:

1. Funds are Owned: Exempt from Deposit Rules.

2. Funds are Borrowed: Treated as Public Deposit (Non-Compliant for Pvt Ltd to accept without strict compliance).

Tax Implication (Section 68):

When an AO scrutinizes a director’s loan under Section 68, they examine the source of funds.

- Scenario A:The director admits to the AO that they borrowed money from a relative or bank to lend to the company.

- Tax Consequence: The “Source of Source” is explained, potentially satisfying Section 68 (subject to the lender’s creditworthiness).

- Company Law Consequence: The declaration under Rule 2(1)(c)(viii) becomes false. The exemption is lost. The transaction becomes an “acceptance of deposit” in violation of Section 73/76 of the Companies Act. This triggers massive penalties (minimum ₹1 Crore) and potential prosecution for the company and officers.

- Scenario B:The director maintains the funds are “owned” to satisfy Company Law.

- Tax Consequence: The director must demonstrate sufficient disposable income or savings in their personal Income Tax Return (ITR) to justify the loan. If their ITR shows low income, the AO will treat the loan as unexplained cash credit under Section 68, taxing it at a flat 60% rate (plus surcharge).

Synthesis: The “Director’s Declaration” acts as a pincer. It forces the director to prove “owned funds” to avoid Company Law violation, thereby increasing the burden of proof for “Creditworthiness” under Income Tax Law.

2.3 The “Current Account” Defense Mechanics: Idhayam vs. Tarulata

The user’s initial analysis relied heavily on CIT v. Idhayam Publications Ltd. to argue that director funding for business exigencies is a “current account” and not a loan. This judgment distinguishes between a commercial loan and a running account used for operational sustenance.

However, contrasting jurisprudence exists. In Tarulata Shyam v. CIT, the Supreme Court dealt with the concept of deemed dividend under Section 2(22)(e). The Court held that even if a withdrawal is repaid, if it possesses the character of a loan or advance at the time of origination, the deeming fiction applies. While Tarulata Shyam focused on outbound loans (Company to Director), the principle regarding the characterization of funds is pivotal.

The Conflict for Inbound Loans:

If a company argues that inflows from a director are “Current Account” transactions to avoid Section 269SS (using Idhayam), they must ensure the substance matches.

- Companies Act Reality: The Companies Act, 2013 does not explicitly recognize “Director’s Current Account” as a category distinct from loans or deposits in the context of exemptions. Rule 2(1)(c) lists specific exemptions. “Current Account” is not one of them.

- Schedule III Disclosure: In the Balance Sheet prepared under Schedule III, valid heads are “Long Term Borrowings” or “Short Term Borrowings.” There is no specific head for “Current Account” that is not a borrowing.

- Risk: If the “Current Account” balance is treated as an “unsecured loan” in the Balance Sheet (to fit Schedule III), it falls under the “Exempt Deposit” category (Rule 2(1)(c)(viii)). If the company argues it is neither a loan nor a deposit, it risks falling into the residual category of “Deposit” under Section 2(31) of the Companies Act (“receipt of money… in any other form”), which would be a violation if not compliant with Section 73.

Conclusion: The “Current Account” defense is a robust Tax defense (specifically for 269SS penalties) but a perilous Corporate Law strategy. A company cannot claim it is a “Current Account” to the Taxman while reporting it as an “Exempt Loan” to the RoC. The inconsistency acts as a red flag for both regulators.

Chapter 3: Form DPT-3 – The Bridge of Transparency

Chapter 3: Form DPT-3 – The Bridge of Transparency

The introduction of Form DPT-3 (Return of Deposits) has fundamentally bridged the information gap between the Ministry of Corporate Affairs (MCA) and the Central Board of Direct Taxes (CBDT). This form serves as a critical compliance touchpoint where the Companies Act requirements directly feed into Income Tax scrutiny.

3.1 The Disclosure Mandate

Form DPT-3 requires companies to report:

1. Deposits: Amounts accepted that fall under the definition of Deposit.

2. Particulars of transactions not considered as deposits: This specifically includes the “exempt” director loans.

The form requires granular details:

- Amount outstanding.

- Date of receipt.

- Rate of interest.

- Particulars of the lender.

3.2 Data Mining and Section 68 Scrutiny

The CBDT and MCA have entered into a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) for data exchange. Form DPT-3 data is now accessible to Tax Officers.

- Automated Scrutiny: If a company reports a high quantum of “Loan from Directors” in Form DPT-3, but the director’s personal ITR reflects low income, the disparity triggers the “Risk Management Strategy” (RMS) of the Income Tax Department.

- Corroborating Evidence: In a Section 68 assessment, the AO can confront the assessee with their own DPT-3 filing. If the DPT-3 lists the amount as a “Loan,” the assessee is estopped from arguing it is a “trade advance” or “current account” to avoid Section 269SS penalties. The statutory filing serves as a admission / evidentiary disclosure of the transaction’s character.

3.3 The Auditor’s Certificate

Form DPT-3 mandates an Auditor’s Certificate for certain disclosures. This places the statutory auditor in a position of responsibility. If the auditor certifies a director’s loan as “exempt” based on a declaration, but the tax assessment later reveals the funds were borrowed (tracing source of source), the auditor could face professional negligence charges under Section 143(12) of the Companies Act (Fraud Reporting) or peer review sanctions.

3.4 Table: Impact of DPT-3 Classification on Tax Assessment

| Classification in DPT-3 | Companies Act Status | Income Tax Consequence |

| Exempt Deposit (Rule 2(1)(c)(viii)) | Compliant (if declaration exists). | Treated as Loan. Section 269SS/T applies. Section 68 scrutiny on source. |

| Advance for Goods/Services | Compliant (if < 365 days). | May escape Sec 269SS (as trade advance). Scrutiny on genuineness of trade. |

| Share Application Money | Compliant (if allotted in 60 days). | Section 68 scrutiny on creditworthiness. No 269SS if genuine equity. |

| Not Disclosed | Non-Compliant (Penalty/Prosecution). | Concealment penalty. Section 68 addition as unexplained credit. |

Chapter 4: Section 68 and the ‘Source of Source’ Conundrum

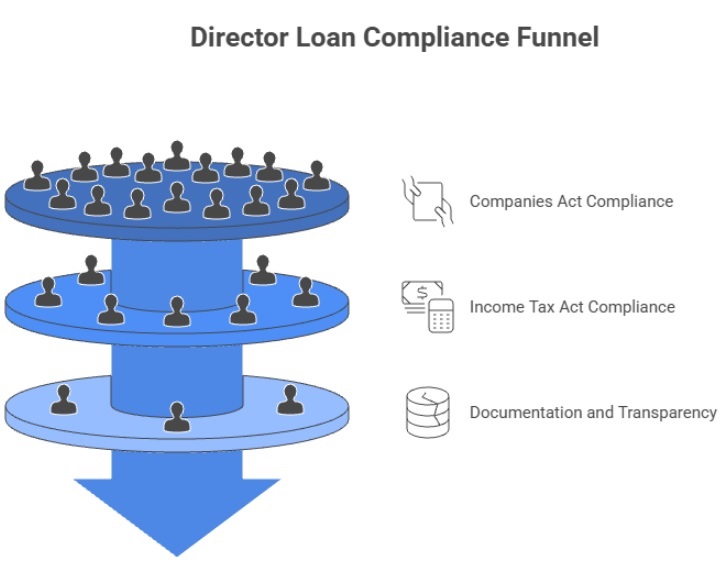

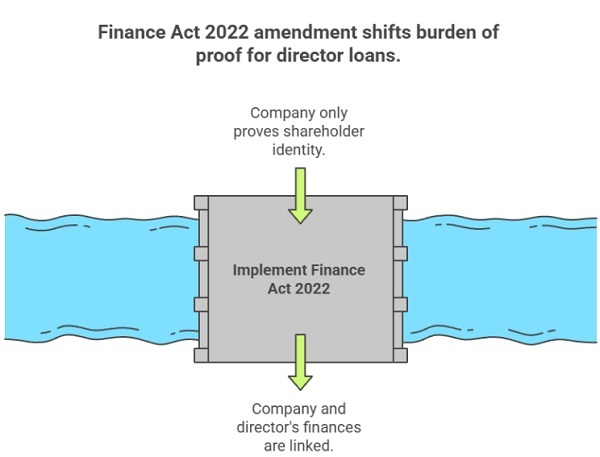

The most significant recent development affecting this interplay is the amendment to Section 68 of the Income Tax Act by the Finance Act, 2022 (effective April 1, 2023).

4.1 Evolution of the Burden of Proof

Prior to 2012, the judicial consensus, led by the Supreme Court in CIT v. Lovely Exports, was that for share capital, the company only needed to prove the identity of the shareholder. The source of the shareholder’s funds was not the company’s concern.

- Finance Act 2012:Added a proviso requiring closely held companies to explain the source of funds for share application money.

- Finance Act 2022:The amendment expanded this requirement to loans and borrowings.

4.2 The “Source of Source” Requirement (Post-2022)

The amended Section 68 states that for loans or borrowings, the explanation is deemed unsatisfactory unless the person who lent the money (the director) also offers an explanation about the nature and source of the sum so credited.

- Impact: The corporate veil is pierced. The company’s tax assessment is now inextricably linked to the director’s personal financial trail.

- Interplay with CA 2013:This statutory mandate compels the director to disclose the “source of source.” If that source is a “borrowing,” the company automatically defaults under Companies Act Rule 2(1)(c)(viii) (declaration of owned funds). The amendment effectively forces a disclosure that could incriminate the company under corporate law.

4.3 Case Law Analysis: Nicg Combines and Garv Associates

Recent jurisprudence highlights the tension in this area.

- In M/s. Nicg Combines P. Ltd., the tribunal analyzed Section 68 additions where loans were taken from directors/shareholders. The AO questioned the creditworthiness based on the low income returned by the lender. However, the tribunal ruled in Favor of the assessee because the lender’s balance sheet showed sufficient assets (loans and advances) to make the loan, establishing that creditworthiness is not solely defined by taxable income.

- In Garv Associates vs. ITO, the Delhi Tribunal reiterated that for assessment years prior to the 2022 amendment, the “source of source” need not be proved for unsecured loans. However, post-2023, the rigorous standard applies.

Implication for “Survival Funds”:

Directors injecting cash for “survival” often do so from personal savings or family pools. Post-2023, if they cannot document the specific origin of that cash (e.g., withdrawal slips, sale deeds), the company faces a Section 68 addition. The Idhayam Publications defense (business exigency) protects against 269SS penalty (mode of transfer) but not against Section 68 addition (source of funds).

Chapter 5: Deemed Dividends and Related Party Transactions

Chapter 5: Deemed Dividends and Related Party Transactions

While loans from directors are the primary focus, the interplay is equally critical when the flow reverses—loans to directors (or their substantial interest concerns).

5.1 The Provision: Section 2(22)(e)

Section 2(22)(e) of the ITA treats any payment by a closely held company to a shareholder holding more than 10% voting power (or to a concern in which they have substantial interest) as a deemed dividend, to the extent of accumulated profits.

5.2 The “Current Account” Defense in Reverse

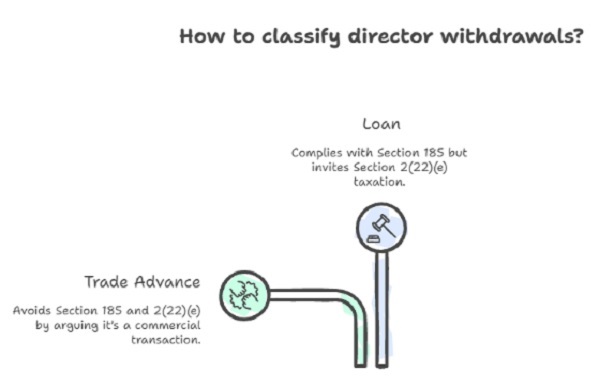

Directors often argue that withdrawals are not “loans” but “current account” transactions or “trade advances.”

- Judicial View: Courts have held that even “current account” debit balances can be deemed dividends if they bear the character of a loan. However, trade advances (commercial transactions) are exempt.

- Companies Act Conflict: Section 185 prohibits loans to directors. If a company classifies a withdrawal as a “Trade Advance” to avoid Section 185 (arguing it’s in the ordinary course of business), it helps the tax defense against 2(22)(e) (trade advances are not dividends). Conversely, if the company treats it as a “Loan” and complies with Section 185 (via special resolution), it invites Section 2(22)(e) taxation.

- Strategic Insight: Compliance with Section 185 (regularizing a loan) acts as evidence for the Revenue to invoke Section 2(22)(e). The company certifies it is a loan via the Special Resolution.

Chapter 6: Interest Payments – Section 40A (2) vs. Section 188

Chapter 6: Interest Payments – Section 40A (2) vs. Section 188

When a company pays interest on a director’s loan, two provisions intersect:

1. Section 188 (Companies Act):Related Party Transactions. The interest rate must be at arm’s length to avoid special resolution requirements. If not at arm’s length, it requires board/shareholder approval.

2. Section 40A(2) (Income Tax Act):The AO can disallow expenditure (interest) paid to relatives/directors if it is “excessive or unreasonable” having regard to the fair market value.

The Trap:

- A company might pay a high interest rate (say, 18%) to a director to reduce taxable profits (arbitrage between 25% corporate tax and director’s slab rate).

- Companies Act: Requires this to be approved. If approved by shareholders, it is valid under corporate law.

- Income Tax: The AO is not bound by the shareholder resolution. They can hold that 18% is excessive compared to the bank rate (say, 10%) and disallow the 8% excess under Section 40A(2).

- Case Law: Courts have generally held that if the Companies Act procedures (Section 188) are followed and the rate is comparable to unsecured market rates (which are higher than bank rates), Section 40A(2) disallowance can be challenged. The “unsecured” nature of director loans justifies a higher premium than secured bank loans.

Chapter 7: Documentation and Defense Strategy

Based on the detailed interplay, a robust defense strategy requires harmonizing documentation across both statutes.

7.1 The Golden Documents

1. The Director’s Declaration: Must be explicitly worded to satisfy Rule 2(1)(c)(viii). “I, [Name], declare that the amount of ₹X is extended out of my own funds and not from borrowed funds…” This document is the shield against Companies Act penalties and the sword for Income Tax scrutiny.

2. Board Resolution: Must reference the declaration and classify the receipt as an “Exempt Deposit” under the specific Rule. It should not use loose terms like “Temporary Adjustment.”

3. Loan Agreement: Essential for establishing the “tenure” and “interest.” Lack of an agreement allows the Taxman to treat it as a deposit (Section 269SS) or the RoC to treat it as a deposit payable on demand (which is restricted).

4. Form DPT-3: Must be filed on time (June 30). The figures must match the Audited Financials and the Tax Audit Report (Form 3CD, Clause 31).

7.2 Defending Cash Transactions (The Idhayam Strategy)

If a company is forced to rely on the Idhayam Publications “Current Account” defense for cash receipts:

- Constraint: Ensure Form DPT-3 does not classify it as a “Loan.” It should ideally be classified under other exempt categories, if possible (e.g., “Advance for supply of goods” if factual), or the company must be prepared to explain the DPT-3 classification in tax court.

- Argument: “The classification in DPT-3 is for the limited purpose of corporate reporting logic which groups all receipts from directors under one head. It does not alter the substance of the transaction which is a running account for business exigencies.”

- Case Law Support: Cite ITO v. Universal Associates regarding business exigency. The Tribunal ruled that “exigencies of business” constitute reasonable cause under Section 273B.

7.3 Managing Section 68 Risk

- Pre-emptive Audits: Before accepting a loan, the company should vet the director’s personal balance sheet. If the director has low reported income, the loan should be avoided, regardless of the Companies Act exemption.

- Linkage: Ensure the “Source of Source” is clean. If the director sold property to fund the company, keep the sale deed ready. The “Owned Funds” declaration under Companies Act must be substantiated by the asset side of the director’s personal balance sheet.

Conclusion: The Unified Compliance Theory

The era of siloed compliance is over. A transaction cannot be a “Current Account” for Income Tax, a “Loan” for Company Law, and a “Trade Advance” for GST. The interplay between the Companies Act, 2013 and the Income Tax Act, 1961 demands a Unified Compliance Theory where the characterization of a transaction is consistent across all statutory filings.

For the scenario of a director injecting funds for survival, the path of least resistance is:

1. Classify as Loan: Accept the reality. It is a loan.

2. Use Banking Channels: Avoid Section 269SS entirely. Cash is a liability.

3. If Cash is Unavoidable: Rely on “Reasonable Cause” (Business Exigency) under Section 273B, supported by the Idhayam judgment, but do not rely on the “Current Account” label to escape the definition of “Loan” if DPT-3 says otherwise.

4. Harmonize: Ensure the Director’s Declaration (for RoC) aligns with the Director’s ITR (for Tax).

This holistic approach minimizes the risk of regulatory arbitrage backfiring, where a defense in one court becomes a confession in another.

*******

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are the personal views of the author and are intended solely for informational and academic purposes. This article does not constitute professional advice, legal opinion, or a substitute for specific consultation. Readers are advised to evaluate the facts of their particular case independently and seek appropriate professional advice before acting on the basis of this article. The author and the firm shall not be responsible for any loss or consequences arising from reliance on the contents of this article.

Tarun Marimganti FCMA | Practicing Cost Accountant | Contact No-8328174243