Summary- State has a duty to collect the taxes from the citizen and use it for their welfare. It is a part of the statecraft. This fact has been given due importance in various historical as well as religious texts. In the modern time, welfare states have overcome the religious dictates and laws/rules etc. have been framed following secular ways.

The modern form of governance was started in India with the Crown taking over the governance from East India Company. The process of prior estimates, budgeting and final reconciliation was started. Use and analysis of relevant statistics has gained momentum, though it is surprising that Kautilya had emphasized it in his celebrated manuscript- ‘The Arthashashtra’. In the federal structure, it was felt that financial resources must be delegated to the provinces for the developmental works. The author has explained the position of revenue sharing between the union and the provinces starting from 1773 and effect of the current issues like introduction of GST. Emphasis has been placed on the reforms started after 1860, often progressing in the trial-and-error methods.

The Government of India Act, 1935 has been a landmark legislation in this direction. After independence, such reforms gathered pace and the process still continues. It should very interesting for every revenue officer to go through the historical developments of the sharing of revenue between the federal and the provincial governments.

Note- The views expressed by the author in the article are his personal views and should not be held as the Official views.

All [state] activities depend first on the Treasury. Therefore, a King shall devote his best attention to it. ” Kautilya’s Arthashastra {2.8.1,2}

Collection of tax is the primary duty of every state. A large state must be divided into several smaller units for administrative convenience, requiring transfer of funds, for conducting welfare activities. A proper administration of tax collection and revenue distribution among the units is a complex and contentious age-old issue. It is being discussed in the background of medieval and modern Indian financial history.

THE FINANCIAL SYSTEM DURING THE COMPANY RULE (1773-1833)

East India Company was granted a Royal Charter by Queen Elizabeth in 1600, conferring the company with the exclusive right of trading in India. In a big move, East India Company obtained the Diwani (rights over revenue and civil justice) of Bengal, Bihar and Odisha, and transformed into a territorial power in 1765. It shared its sovereignty with the Crown and was answerable to the British government as well as its shareholders. The relation between the Crown and the Company was not well defined. The Crown desired the benefits of the venture but did not want to get directly involved in warfare and unethical methods adopted by the merchants. The Company had its own charter, which went on from earning profit to acquiring territories. Slowly, warfare became expensive, and shareholders the poor return on their capital left them dissatisfied. Company’s servants were amassing personal wealth and stories of their oppressions were reaching London. The Company was now required to maintain ‘Territorial Accounts’ and ‘Commercial Accounts’ separately in each Presidency. However no uniform system prevailed.

In the acquired areas. East India Company was taking care of external threats, internal peace and currency related issues. Expenses on sanitation, education, and transport facilities were limited to urban pockets only. Company was generating almost half the revenue by the sale of opium. A Select Committee of Parliament was set up in 1772 to inquire into the financial matters of the Company. Based upon the findings of this inquiry, the ‘Regulating Act’ was passed in 1773. Constitution of the Company, as well as its administration in India were modified accordingly. The Governor in Council of Bengal was now made the ‘Governor General in Council’, empowered to supervise the work of other two presidencies. A Board of Control was formed to oversee the Indian Policy through Pitt’s India Act of 1784. In 1793, a covenanted civil service was introduced. The process of centralization was further reinforced by the Acts of 1793. 1813 and the Charter Act of 1833. It established an Imperial system of governance, depriving the governors of Madras and Bombay of their legislative powers, and the Governor-General of Bengal became the Governor-General of India. The Act[1] of 1833 created a real ‘Central’ Government of India, having authority over the entire territory possessed by the British in India.

FLAWS IN THE FINANCIAL SYSTEM

The commercial accounts of East India Company were separated from the political account by the Charter Act of 1813. The East India Company, thereafter, functioned more as an administrative body rather than a trading concern. Bengal Presidency was revenue surplus, but other two Presidencies continued to incur losses. Around 1834, there were three types of taxes prevailing in India, namely central, provincial and local taxes. The tax collection methods of each of the Presidencies were different. Continuous deficits plagued the system, requiring frequent attention of the British Parliament. Efforts to restrict expenditure with improvement in the system of audit & accounts were undertaken. It was evident that the taxation system was illogical, outdated, and unable to meet the cost of administration. Absence of a centralized and an appropriation budget to exercise overall control were badly felt. Unmonitored expenditure, dependence on land revenue and absence of systematic financial management worsened the scene. Till 1833, the Presidency Governments of Bengal, Madras and Bombay had the power to frame Regulation, having the force of a law.

After 1833, there was a continuous growth in the powers of the Government of India. Core functions were embodied in the ‘Supreme’ Government at Calcutta. The entire administration of India, general and financial, became centralized at Calcutta and the other Presidency governments were reduced to subordinate administrative units. Finance and commerce were separated to streamline the financial administration. Still the finances were held under the ‘Home department’. Though inconvenient, yet the revenues were required to be paid into the treasuries all over the country to the credit of the Governor-General in Council. The provincial governments assisted only as agents of the Supreme Government, entirely dependent for allotment of sums for their recurring and capital expenditure. To streamline the fiscal policies, in 1843, a separate office of Financial Secretary to the Government of India was created in London.

EAST INDIA COMPANY LOSING ITS GRIP (1852-1858)

The supreme Government in the Bengal Presidency lacked the resources and administrative machinery to supervise the vast country like India. The Council at Calcutta did not have representatives from the other Presidencies. The Governor General’s instructions were seen as interference, causing distress. The irregular exchange of accounts reflected neither economy nor efficiency. The supremacy of Bengal was due to the larger revenue and its surplus. The central Government was accused of treating the provinces unequally. A Select Committee was formed by the British House in 1852 to review the administration of the British territories in India. A scheme of decentralization was suggested by the Committee to remedy the situation by assigning a certain sum towards public work expenses. The House however supported a supreme Legislative Council at Calcutta with the representatives from other Presidencies. The Great Mutiny of 1857 is a landmark in the history of India. It passed over the Northern India like a thunder, causing a war like destruction. It also blew away archaic systems and institutions. The administration of the Company was serving only its commercial needs so far. As the commerce receded, the old system could no longer be followed. A proper budgeting of income and expenditure was need of the hour. The accounts were in mess and the financial machinery broke down under the strain of the Mutiny.

The British Parliament had no control over the Indian revenues so far, except that no money could be spent on military expenditure, outside British India without the consent of the Parliament. The British army stationed in India and the Indian army were a charge on the Indian revenue. The Act of 1858 laid down that the expenditure of the revenues of India shall be subject to the control of the Secretary of the State in council and no grant or appropriation of any part of these revenues shall be made without concurrence of a majority of votes at the meeting of the Council.

Under the East India Company’s administration, taxation was never based on any financial or ethical principle. Till a levy did not create a revolt like situation or was financially unviable, it was treated as an eligible tax. Heavy burden was placed on the poor and the helpless, while the earning of company’s servants and the Indian elites was untaxed. At the time of takeover in 1858 by the Crown, nothing like a ‘budget’ existed. The Company’s double entry system was found to be unsuitable for administrative purposes. No unified Finance Department was in existence linking the Union and the Provincial revenue with the corresponding expenditure. Immediately after the takeover, significant financial reforms were enforced. The Government of India Act, 1858 passed by the British House provided for a strong centralized Government. The Queen appointed Lord Canning as the Viceroy of British India.

The office of President of Board of Control was replaced by the fifth Secretary of State by the Government of India Act 1858. The expenditure of the public revenues, as well as the appropriation of funds were controlled by the Secretary of State. Annual statement of Revenue and Expenditure of British India was to be laid before the House annually. The home charges on account of military and equipment, stores and pension and allowances were controlled accordingly. To provide independent scrutiny, the Act ruled that an auditor of Indian Accounts should be appointed. The budget was not subject to debate, as the House was merely informed of the accounts of the last completed year and revised estimates of the current year. However, the House had an opportunity to review every aspect of Indian affairs. Even the salary of the Secretary was a charge on India. A financial statement commonly known as the Indian Budget, was placed before the house, followed by a formal resolution. Discussions on financial matters were not encouraged. The friction between the centre and the provinces continued. The revenue was pooled to a common fund. Centralization of finances thus burdened the Finance Department to raise the revenues for the self, as well as for the provinces, which showed no interest in economizing their ballooning expenditures.

1860- A LANDMARK YEAR IN INDIAN FINANCIAL HISTORY

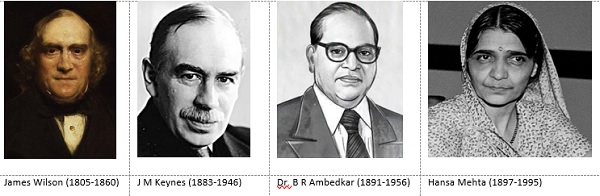

The aim of the Government of India at absolute control of the financial administration was assisted by faster transport and upgraded post & telegraph facilities. Indian Finance Department was reorganized by appointing a Finance Member to the Governor-General’s Council. The modern financial system of budgeting and accounting were thrust upon. Improvement in the currency system and fresh load of taxation followed. It was accepted without much protest. James Wilson (3rd June 1805 – 11th August 1860), was a Scottish banker, economist, and a politician. He is considered as the Father of Indian Budget System. He had also founded ‘the Economist’ a weekly news journal, in 1843 and the Chartered Bank of India, Australia, and China’ in 1854. Wilson is credited with the introduction of Income Tax, Paper Currency, and remodelling of Indian financial system. Wilson believed that the Government had overborrowed in the past and increase in taxation coupled with a reduction in expenditure could alone lead to financial equilibrium. On the 18th February 1860, James Wilson presented the First Indian Budget[2]. He held that in a vast country like India with multiple provincial governments, framing the estimates of income and expenditure before the commencement of the year would be advantageous. The process of ascertaining real statistics was a challenging work. In Wilson’s budget proposals, a separate account was to be kept for the one percent duty, which was to be applied for the local purposes by the Provincial Governments. He called upon all classes to contribute to the Exchequer. Indian budget for the ensuing year was formulated before the close of the financial year without considering the results of the completed year. After it, normally three Statements were required in the Indian budget –Budget Estimate for the ensuing year, Revised Estimate of the expiring year and the Actuals of the previous year.

The Income Tax Act 1860 provided that a Separate account to be kept for 1 percent duty, under its sections CXCI to CXCIV. It was the first step towards the fiscal federalism. Yet, it was not the first time, when the legislation contained the provisions for appropriation. An amendment dated 8th February 1860 to the Act 111 of 1857, related to the Trespasses by Cattle provided for the appropriation of surplus fines etc. to be used by the local Government.

Charles Trevelyan, the Governor of Madras, at that time, was a senior Civil servant and a seasoned administrator. He opposed imposition of new taxes and refused to collect them in Madras. He wrote[3]– “. . . of the manner in which these tremendous taxes are proposed to be applied to all the various peoples, nations and languages, composing the British Empire in India, that there are no data upon which any reliable calculation can be made of their results. .”. Secretary of State for India took strong exception to his observations, particularly, his action in publishing the correspondence on the subject. Matters escalated so far that Charles was recalled from the Governorship of Madras. It is said that Charles Dickens likely based ‘Tite Barnacle’, a character in his novel Little Dorrit, on Trevelyan. He was sent to India again in 1862-65 as Member Finance to Viceroy’s Cabinet.

EXPERIMENTAL YEARS- (1861-1870)

Though James Wilson had drawn up a scheme for enlarging the powers of the provincial government, he did not live to see it through. As a part of the ongoing reforms, the Indian Council Act 1861 was passed. The Act restored the legislative powers of the provincial governments, earlier curtailed by the Charter Act of 1833. Wilson’s successor Samuel Laing insisted on the devolution of powers to the provincial governments. In his budget speech[4] of 1862, he described Income tax as a failure and asserted[5] – ‘I am as strong as ever in favour of the principle of local taxation for local objects’. He suggested that the provinces may raise revenues through fresh taxation for meeting provincial needs, laying the foundation of the provincial budgets and more taxes, but the proposals failed to take shape. His successor, Charles Trevelyan did not repeat his earlier mistake to even think of scrapping the Income tax but allowed it to lapse in 1865. William Massey, next Member Finance, also found it was difficult for the Imperial Government to manage the whole of the finances of India[6]. Due to unsatisfactory financial position, Massey put forward the scheme of decentralization in January 1867. The details of the plan were worked out by Richard Strachey, who looked after finances in absence of Richard Temple. He was an ardent advocate of decentralization. Strachey’s note of 17th August 1867 gave the description of the scheme. He wrote- “the distribution of the public income degenerated into something like a scramble, in which the most violent had the advantage, with very little attention to reason; as local economy brought no local advantage, the stimulus to avoid waste was reduced to a minimum and as no local growth of the income led to local means of improvement, the interest in developing the public revenues was also brought down to the lowest level.”

In 1867, Lord Mayo decided that some financial responsibility had to be delegated to the provincial governments. At first, a fixed sum was given to each, and thus increased expenditure could be met either by more careful management or by local taxation. Sir Richard Strachey’s scheme for decentralising the financial administration of India formed the basis of the policy afterwards. It was carried into effect by his brother Sir John Strachey under Lord Mayo and Lord Lytton. Sir John Strachey a member of the governor-general’s council in 1868, wrote- “The result was a complete absence of real financial control frequent wrangling between the supreme and the provincial governments, and the interference from the former, not only in financial but in administrative details, with which the local authorities alone were competent to deal.” Some ten years later, Lord Lytton, acting on the advice of Sir John Strachey, substituted fixed grant with a share in the revenue. So many members of the ‘Strachey’ family were occupying influential posts in India that sarcastically, it was called a ‘Strachey’ government of India.

A division of items and revenue was made between imperial and the provincial governments under the heads- imperial, provincial and divided. Salt, opium, customs, and tribute were wholly imperial. Land revenues, stamp, excise and assessed taxes were divided between imperial and provincial governments. The provincial governments took all the receipts under registration. In 1868, Lord Napier, Governor of Madras, made a deep analysis of the merits and demerits of federalism for India, favouring federal system. He had no faith in half-measures and therefore opposed the Massey scheme. The finances showed no improvement due to excessive centralization. Budgets which had estimated huge surpluses closed with deficits. However, the dreams of Laing and Massey were realized by new Viceroy of India, Lord Mayo, in 1870. Due to the seriousness of the matter, he resorted to downscaling expenses and imposed additional taxation. Soon after, he initiated the first successful measure of decentralization with transfer of certain administrative work to the provinces. The provinces were to be allotted fixed assignments to meet these charges.

BUDGETS BY ASSIGNMENTS (1870-92)

On 14th December 1870, the Government of India published a resolution which conveyed the details of the proposed system which was based on provincial assignments and to allow the provincial government to levy taxes. The Resolution proposed that the Governor-General in Council would maintain fixed assignments or “Provincial Services”, which could not be altered without prior consultation. The latter, in turn, had to frame local budgets based on these assignments and to allocate these assignments among various services. This system commenced the system of Provincial Budgets. Deficits, if any, were to be met through additional assignments from the imperial treasury. This scheme came to be known as the ‘Budget by Assignments[7]’. The Assignments made to the Provincial Governments for the services that were incorporated[8] into their budget, published in the Gazette. A separate budget was formulated for each province, leaving the services at their choices.

Mayo’s Scheme of 1870 also was subject to harsh criticism, alleging that it would diminish the powers of the Centre and would encourage extravagance in the local Governments. Nevertheless, the scheme rescued the finances from a state of chronic deficit and brought some equilibrium. Decentralization of finance brought some harmony between the central Government and the provinces. Lord Mayo succeeded to reform the system in his brief tenure of three years. Further enlarging the financial Power of Provinces In 1872, Sir John Strachey suggested[9] that some heads of receipts be transferred to the provincial governments to meet the charges transferred to them. Strachey wrote, “Real financial responsibility in the provinces needs that they should be given a stimulus for administering revenue collection properly”. He suggested that additional items be incorporated in the provincial budgets along with handing them some expanding revenues to meet the growing charges. However, it appeared to be premature, creating misgivings, and in 1873 the Provincial Budgets were appended to the Imperial Budget. Sir Richard Temple’s detailed examination of the budgets from 1861-72 revealed that a series of six years constituted a cycle in Indian Finance. However, the subsequent events did not conform to such frequency.

The system of budget by assignments was rigid. Sir Strachey held the view that as long as the provinces collected revenues for the Government of India, they would not care to its check evasion. Lord Lytton supported the proposals of Strachey in his speech before the Legislative Council in 1877. Subsequently, the system of budget by assignments was changed to a system of Budget by Assigned Revenues[10]. More departments were transferred to the provincial management; and certain minor heads of revenues were also transferred to meet the expenditure. Since the receipts did not meet the whole expenditure, the old system of assignments co-existed. They had no share in the land revenue, which was the largest source of revenue in India. It was held that Provinces be given some share in it, so that they make effort to increase it. The remedy was devised by Sir John Strachey, but the practical application was made by Lord Ripon and his financial Member Major Evelyn Baring. Sources of revenue were classified as Provincial, Imperial and Divided. The revenues from the ‘Divided’ heads were to be shared between the imperial and provincial governments in a certain ratio. This system came to be known as the system of Budget by Shared Revenues.

Due to this, there was an increase in the revenues of the provinces in 1891-92 as compared with the estimates for the contracts of 1887-88 to 1891-92. Nevertheless, pains in adjustment of the budgets continued, as the expenditure outstripped the revenues assigned to provinces. It was proposed that instead of fixed assignments, a fixed percentage of land revenue be given to the provinces. Thus, the provincial governments were involved in the collection under the ‘divided heads’ in their jurisdictions, in addition to the sources of revenue. The settlement brought about the integration of the financial interests, both central and provincial. Now, they shared not just the revenue receipts but also the expenditure on certain heads. Such revisions under Lord Ripon’s scheme were to be made after the expiry of five years, called the quinquennial settlements. Lord Ripon’s scheme was a historical landmark in decentralization of finances. The concept of resources sharing under different heads incorporated in the present Constitution of India can be attributed to Ripon’s Scheme.

Subsequently, the Indian Councils Act 1892 was passed to widen and expand the functions of the Government of India and to give to the Indians a greater role. The Act, for the first time, enabled the Legislative Councils to discuss the Annual financial Statement in the Centre as well as the provinces, without granting them any control over the budgets. The Act of 1892 made significant advances over the Act of 1861. Still, the expansion seemed illusionary, belying hopes of financial autonomy.

During the period 1892-93 to 1896-97, the government again briefly reverted to the system of budget by fixed assignments. Furthermore, the spread of plague, famine and financial depression led to the revised settlements of 1896-97. It increased the share of the provinces. The provincial governments grumbled at the greed of the central exchequer, resorting to periodical resumptions of provincial balances to the central treasury. This demoralized the financial administration of the provincial governments. The provinces could not benefit from their efforts in fostering and economizing the revenues. Demands for doing away with the ‘divided’ heads, with a clear division between central and provincial revenues were raised. However, this scheme had to wait for twenty more years before it could be implemented. Thus, the limited power delegated by the Indian Council Act of 1861 to provinces, was effected only in 1892.

PERIOD OF REFORMS- SHARING OF REVENUE (1904-1919)

The quinquennial settlements encouraged thrift in the initial years and extravagance in the later part of the five-year period. To resolve such defects, Lord Curzon proposed a scheme of Quasi-Permanent Settlements. Central Government’s improved revenues in 1904, made it possible to enter contracts with Provinces on a more stable footing. Henceforth, the contracts were to remain unaltered, except when it was found that it was unfair to a Province, or to Government of India. Owing to this proviso, their settlements were termed as quasi-permanent. The deficit in the provincial account was to be made good by a fixed assignment from Land Revenues.

The Quasi-Permanent Settlement gave the provinces a more independent position and a more enduring interest in the management of their resources, eliminating the risk and uncertainties of an unfavourable settlement at the end of every five years. After Lord Curzon left India, the tension between the central Government and the provinces escalated again. Viceroy Lord Minto appointed a departmental committee to enquire into provincial Governments’ administrative and financial relations with the Government of India. The commission recommended relaxation of control exercised by the higher authorities and the simplification of administrative methods, while stating that they were ‘generally satisfied’ with the present financial relations. A gradual abolition of ‘divided’ heads of revenue and enlarging the powers of the provincial sphere was also recommended.

Morley-Minto Reforms increased the powers of legislatures by enlarging, both central and provincial. They could now pass resolutions (which may not be accepted), ask questions and supplementary, vote separate items in the budget, but the budget could not be voted upon. One Indian, Satyendra Sinha was appointed to the Viceroy’s Executive Council in 1909, but the control of the centre was not relaxed. In a dispatch to the Secretary of State, the Governor-General in Council expressed his anxiety over the bickering between the central and provincial governments. Anxious to improve the situation, the Government of India asserted that advancing greater permanency to the settlements was the only way forward. The Budget of Government of India for 1910-11 portrayed the compositional changes in the Imperial Budget, into ‘wholly provincial’, ‘wholly imperial’ and ‘divided’ heads, as introduced in 1882.

The expenditure was divided under home charges, payment of interest on debts and the maintenance of forces. The central administration and the foreign affairs were wholly Imperial, including departments like post and telegraph, mint, and the railways. Irrigation was divided between two accounts. The provincial governments attended to the education, police, health, and sanitation. Provincial governments had a larger power and responsibilities, but they were merely the delegates of the government of India and worked under its approval and control. They had no borrowing powers, and their budgets were subject to prior sanctions.

British economist John Maynard Keynes, well known for his theory on employment, was in India office, London from 1906-08. In May 1913, he wrote his first book- ‘Indian Finance and Currency’. Chamberlain, the Chairman of the Royal Commission had suggested his name as a member to this committee on Indian Currency and Finance. On the 5thMay, 1913, first meeting of Commission was held, and final report was submitted on the 9th June 1914. Keynes has given valuable suggestions on Indian currency and gold exchange standard. Keynes was again appointed Vice-Chairman of the Indian Fiscal Commission on tariff policy in 1921 and authored its report. Chairman of this Commission, Ibrahim Rahimtoolah had fought a hard battle with active support of Gopal Krishna Gokhale[11] and Madan Mohan Malviya over the previous decade to get the government support for Indian industrialization. A Tariff board was constituted in 1923, as per Committee’s recommendations. Keynes was critical of the Indian habit of accumulation of gold and advised the Government to impose high import duties and to discourage this tendency by all possible means.

A proposal for provincial taxation, had to be referred for sanction to the Government of India and to the Secretary of State. Chelmsford and Montague found that system of strict control was preventing the provincial development, requiring changes. By the Government of India Act 1919, a provincial government was now permitted to raise loans on the security of revenue allocated to it. As per the Montague-Chelmsford Reforms Report (1918) the ‘Diarchy’ system was implemented, paving the way for the foundation of a Federal system in India. It required the separation of the functions and finances of the provinces and the Central Government. The functions of provincial government were split into the Executive, responsible to the Governor, and the other under the Ministers responsible to the Legislature, corresponding to the Reserved and Transferred subjects. The Reserved subjects were administered by the Governor through his bureaucrats. The Transferred Subjects were to be administered by the Ministers responsible to the Legislative Council. The Secretary of State and Governor General had more control of Reserved Subjects than the Transferred Subjects. Thus, day-to-day control over Provincial expenditure by the Central Government was relaxed to a great extent empowering the Provincial legislatures to enact their budgets.

A Finance Department was set up in every province. The Act also bestowed on the provinces the right of taxation and granted borrowing on security of their revenues. The prior approval of the Governing-Council and Secretary of State was required for raising loans in India and abroad respectively. Owing to these difficulties the Provincial Governments were dependent on the Central Government for audit, accounts, and borrowings. So, it was halfway between control and autonomy. The 1919 Act gave the provinces considerable latitude in matters of financial administration, as there was no separation of cash balances of the Centre and the provinces. There was a single ‘public account’ on which both operated. The provinces were given unlimited right to overdraw their accounts, but they had to reimburse the amount withdrawn, before the close of the financial year. The provision of ‘Ways and Means’ continued to be a central responsibility.

Chelmsford and Montague condemned the divided head. It was resolved that each government will raise its own revenue and the divided head will be abolished. As recommended by the Decentralization Committee, Lord Hardinge converted the ‘Quasi-Permanent’ settlement to ‘Permanent-Settlement’. The principles of allocation of resources remained unchanged, except that the fixed assignments were reduced. The provinces had now larger shares in the sources of revenue. This permanent settlement existed till reforms of 1919. It also proposed the setting up of a Public Service Commission. Subsequently, the Central Public Service Commission was established in 1926, known as Union Public Service Commission after independence.

CONSOLIDATION OF THE PROCESS OF DEVOLUTION (1920-35)

A scheme of division of revenues contained in the Government of India Act, 1919, was expected to upset the budget of the central Government. Initially it was suggested in the Joint Report (1918) that such deficits would be made up by drawing from the surpluses accrued to the provinces. However, this proposal drew strong opposition from the Provincial Governments. The whole of Income tax was to be handed over to the Government of India, which was disputed by Bombay. The difficult situation thus entailed the creation of this Special Committee to inquire into the financial relations between the provincial and central Governments. The Meston committee recognised that the claim of Provincial Governments cannot be excluded from the direct taxes, yet it advised against the division of income tax. Division based on domicile was also difficult, as the taxpayers were free to do business in one province and pay tax in another. After pondering through the taxable capacities and the economic position in detail, the committee recommended a fixed ratio of contributions to be put into effect after an interval of time. These contributions, called the Meston Award, were to be abolished when the financial health of the central Government improved.

The Joint Select Committee of Parliament on Draft Rules made under the GOI Act 1919 suggested that Provinces should receive 3 pies in each rupee by which assessed income of any year exceeded of the year 2021. It was embodied in Devolution Rule 14 and 15. It did not garner any significant revenues for the provinces but marked as the beginning of use of income tax as a balancing factor. The classification of subjects into ‘provincial’ and ‘central’ was also made in the next budget. Besides, the annual contribution of the provincial governments to the central Government as per the Meston Award was also clearly delineated. The budget also suggested that the single cash balances to be maintained by the Government of India. The exorbitant war finance led to deficiency in resources. Provincial budgets ran into deficits straining its performance. The Government of India resorted to fresh taxation. Income Tax was allotted to the Central Government. In the budget for the year 1924-25, a clean separation of revenues was made between the Central Government and the Provinces. Land revenue and irrigation receipts were delegated to provincial heads. The entire revenue of India was divided between the Central Government and the Provinces, dispensing with the ‘Divided head’. Poor railway earnings caused anxiety. Acworth Committee reported that inclusion of irregular railway earnings made the Central budget unpredictable. In September 1924, the railway finances were separated, receiving fixed annual contributions and paved way for a separate Railway Budget.

An Enquiry Committee was set up for determining the allocation of the share of the Income Tax between the Imperial and Provincial Governments under Rule 15 of the Devolution Rules in 1925. The Committee was directed to make a general enquiry into Indian Taxation, division of sources of revenue and the structure of the financial relations between the Centre and the Provinces. It was also given mandate to report on the suitability of alternative sources of taxation.

The whole gamut of taxation was visited by the Enquiry Committee. It received reports and recommendations from all major provinces in respect of various types of taxes. It also studied the methodology adopted in other countries in this regard and suggestions of all major economist and administrators of taxes. The report, compiled in several volumes, recommended that if sizable addition is to be made to public revenues, a part of it must come from the masses through taxes having a wide base. It was felt that existing tax structure and rate did not fully tap the taxable resources. The Commission also considered other taxation, such as a low rate of wealth tax. The Commission suggested some reduction in tax tagged with reliefs for savings and investment. An increase in excise taxes and non-tax revenue, moderate land revenue surcharges, agricultural income-tax, property taxation and taxes on transfer of property by local bodies and widening of the sales tax were also suggested to. Stamp and restrictive duties were proposed to be kept with Centre. The whole of land revenue, taxes on irrigation and excise on country liquor were offered to the provinces.

Dr. B R Ambedkar reviewed[12] the report of this Taxation Enquiry Committee, which makes an interesting article to read. He observed– “I do not at all wish to be unfair to the Committee. But I am bound to say that in this respect the Report of the Committee is a most disappointing document. The Committee has devoted a great deal of space to the detailed history of the various sources of taxation in India. So far so good. But it would have been far better if the Committee had devoted half of that space in discussing the incidence of each tax separately. But this the Committee has entirely omitted to do. If that was done, the Committee would have been in a better position to deal with the question of the distribution of the burden of taxation and of the elimination of the iniquitous taxes. That it has not been able to do as well as was to be expected from a Committee which has cost the country nearly Rs. 4.5 lacs exclusive of printing is due to the fact that it forgot to consider the question of incidence, which, after all, was the most important part of its enquiry”.

After some improvement in economic conditions, Basil Blackett, in budget statement for 1928-29, abolished the Meston Award. In 1930, Indian Statutory Commission submitted its report, endorsing the general principles of division of resources by Lord Layton. It accepted the revenue sharing proposed by the Taxation Enquiry Committee allowing half of the income tax be assigned to the provinces and suggested that proceeds of agricultural income tax be allowed to provinces.

In the same year, another committee named, Indian States Enquiry Committee was set up, as recommended by the Round Table Conference. The Committee was to determine how far and in what respects the federal finance would be contributed on a uniform basis by the federal units, how it was affected by the ascertained existing rights of certain States, and contributions of a special character. However, the Committee restricted itself to the receipts from ceded and acquired areas and financial adjustment between some States and British India on their entry into Federation. It has no relevance today, except its observation that the committee viewed interstate tributes as anti-federal and hoped that they would disappear.

The first Peel Committee of 1931 suggested that income tax be transferred to provinces, keeping the machinery of collection with Centre, and all the indirect taxes. Percy Committee 1932 was set up to determine the sharing ratio of direct taxes with provinces. It suggested the residential status as a sound basis, as such the corporation tax, tax paid by residents in federally administered areas and tax on federal government employees’ salaries be retained by the Central Government. A fair level of estimation was permitted for ascertaining the divisible shares. It also suggested that share should not be revised every year for the sake of stability, the Centre may impose surcharge and the population be made a basis for grants to provinces. The second Peel Committee in 1932 suggested that apart from the above Percy formula, the Central Government should retain a block amount of the provincial share of income tax. Power to levy surcharge on income tax for the benefit of provinces was also suggested. Amendment to grant Bengal a share from the tax on jute was also proposed. A Joint Parliamentary Committee in 1933-34 agreed with the proposal of fifty percent income tax sharing but did not favour surcharge sharing.

PREPARING FOR FINANCIAL AUTONOMY (1935-1950)

The Government of India Act, 1935, established a clear federal system with provinces and Indian states as two distinct units. Under the Act, legislative powers were distributed under three lists: the Federal list, the Provincial list, and the Concurrent list. The revenues of India were thus classified as – a) Taxes levied, collected and retained by provinces b) Taxes levied, collected and retained by central Government c) Taxes levied and collected by central Government but assigned to provinces (with power to the centre to impose a surcharge) d) Taxes levied and collected by central Government with a power to assign a share to the units e) Taxes levied and collected by central Government and partly shared with provinces.

This Act made the revenues and finances of the provincial government distinct from those of the federal government. The act also provided for the collection and retention of levies by the federal government and spelt out details for the distribution of financial resources and grants-in-aid to provinces. As per the act, to be charged on the revenues of the federation. The Government of India Act, 1935 established the basic structure of fiscal federalism in India, one that survives today. Otto Niemeyer Committee determined the share of provinces in 1936 by fixing the scales of distribution of income tax partly based on population and partly on the place of payment. Bombay and Bengal received the highest percentage (20%) with varying percentage of grants fixed for different provinces.

The Constituent Assembly was constituted in 1946. The federal framework had evolved over a period. However, the nature of the relationship between the proposed federal government and the provinces of British India and Princely states could be resolved only after independence. A Fiscal Committee set up in 1948, gave various suggestions to protect industries and renaming the Tariff Board as the Indian Tariff Commission. Excise on liquor was a much-debated subject by the framers of the Constitution. Hansa Mehta, a member of the Constitution committee, took a balanced stand on Prohibition. Instead of advocating a blanket ban or complete freedom, she believed the State shouldn’t manufacture neither sell liquor and nor police it. Clarifying Mahatma Gandhi’s stance on Prohibition, she said[13]– “But, what Gandhiji desired was that the State should not manufacture liquor, nor should the State sell it and that public bars should also be closed so that there may be no temptation for those who are susceptible to drinking. But, I do not think that Gandhiji ever desired that we should raise an army of police. Gandhiji never desired that we should spend good money on police. We are prepared to forego the tainted income; but is there any reason why lakhs and lakhs of good money should be spent on excise police? It will only add one more source of corruption, and we have enough of corruption in this country. Another thing, it will perpetuate the sales tax and people who are already burdened with taxes are groaning under the sales tax”.

The scheme of division of resources adopted in the Indian Constitution follows broadly the financial provisions of the Government of India Act 1935. The Indian Constitution chose to divide the sources of revenue on the principle of efficiency and to avoid double taxation and duplication of tax machinery. Draft Article 94 (later Article 114), debated on 10th June 1949, laid the procedure for the Appropriation Bills. The Indian Finance Enquiry Committee was set up under Chairmanship of Shri T T Krishnamachari in 1948 to consider the financial integration of States. Scope of Committee was limited to Part B states, including merger of Baroda and Bombay. In absence of a regular Finance Commission, as mandated by Articles 273 and 275 of the Constitution, Deshmukh Award Committee was set up. Some states had objected to allocation of proceeds from the income tax and jute export duty. However, the Committee was restricted to reallocation of the funds of divided states like Bengal, Punjab and Assam and to reallocate the funds meant for Sind, NWFP to Part A states.

The Constitutional provisions to Centre about taxation, unlimited borrowing powers and currency printing placed it in a commanding position. Recognising the fact that the financial resources of the States may prove inadequate, Constitution premeditated the flow of funds from the Centre to the States, through three main channels-Statutory transfers through the Finance Commission, planned transfers through the Planning Commission (now abolished), and discretionary transfers for Centrally Sponsored Schemes. Apart from direct transfers, resources flow to the States indirectly through the channels like establishment/expansion of Central public sector enterprises, subsidised lending by banking/financial institutions and subsidised borrowing by the States from the Central Government and the banking system. A provision for annual grants-in-aid of revenues under Article 275(1) is also provided for. Provision of Grants-in-aid to the States for the welfare of Scheduled Tribes and for raising the level of administration in Scheduled Areas and separately for Assam has also been prescribed, indicating flexibility of India’s Constitution for the distribution of financial resources between the Centre and the States.

FINANCE COMMISSIONS

The Finance Commission, a constitutional body, was formulated under Article 280. It is constituted every five years by the President of India to review the state of finances of the Union and the States and suggest measures for maintaining a stable and sustainable fiscal environment. It also makes recommendations regarding the devolution of taxes between the Centre and the States from the divisible pool which includes all Central taxes (excluding surcharges and cesses) and grants-in-aid of revenues of the States. The Committee can suggest allowances for any contributions of special value which the States in question might have made. Though the taxes levied by the Centre and the States are mutually exclusive, yet all the taxes and duties levied by the Centre are not meant entirely for the Centre. In fact, revenues from certain taxes and duties leviable by the Centre are totally assigned to or shared with the States in accordance with their needs. The first Finance Commission was appointed in November 1951. So far 15 Finance Commissions have been established.

After independence, several committees and commissions were set up time to time, to improve the working and collection of the Direct taxes. Some of which are- Taxation of Income (Investigation Commission) 1947 (declared ultra-vires by Hon’ Supreme Court in 1956), Vardhachari Commission (1951), John Mathai Commission (1954), Direct Taxes Administration Enquiry Committee 1959 & 1961, Law Commission Report, Bhoothlingam Committee (1968), Direct Taxes Enquiry Committee (1971), Choksi Committee (1971), L K Jha Committee (1987), Kelkar Committee (2002) and Tax Administrative Reforms Commission etc. Such efforts improved the structure and collections of taxes, as well as made them less cumbersome.

Article 280(3) requires the Finance Commission to make recommendations to the President, though not binding upon the Government of India. However, to safeguard the interests of the States in the Union taxes, the Constitution provides (Article 274) that no bill or amendment which (i) varies the rate of tax in which the States are interested; (ii) affects the principles on which moneys are distributable or (iii) imposes any surcharge on any such tax for the purpose of the Union, shall be introduced or moved in the Parliament except on the recommendation of the President. The Centre has generally accepted the major recommendations of the Finance Commissions though some were partially accepted. Article 268 to 293 under Part XII deal with the provisions of financial relations between Centre and States.

GOODS AND SERVICES TAX- THE GAME CHANGER

The introduction GST is unarguably the most important structural reform in the field of indirect taxation. GST is a consumption-based value-added tax on goods and services with dual levy by both the Union and the States. By amalgamating a large number of Union and State taxes into a single tax, GST is expected to remove the ill effects of cascading of taxes, facilitating better business environment. Both the Union and the States have concurrent powers to levy tax on a common base. States levy and collect State GST (SGST) and the Union levies and collects the Central GST (CGST). An integrated GST (IGST) is applied on inter-state movement of goods and services, kept in a separate account, and distributed between the two. Finally, taxation from the ‘origin’ to ‘destination’ principle on goods/services has been adopted.

With many taxes subsumed under it, GST now accounts for 35 per cent of the gross tax revenue of the Union and around 44 percent of the States. GST has become a critical factor in Indian federal finance. This transformation has also made substantial enhancement of the share of the States in the divisible pool of taxes (42 per cent by the FC-XIV). The GST law has guaranteed State Governments revenue growth of at least 14 per cent over the 2015-16 collection of subsumed taxes for a period of five years. Any shortfall in this growth is being transferred by the Union Government from a separate cess being collected for the purpose. States’ revenue on account of SGST is thus protected from 1 July 2017 to 30 June 2022. From the consumer’s point of view, the biggest advantage would be in terms of an estimated reduction in the overall tax burden. The assignment of concurrent jurisdiction to the Union and the State for such levy is being taken care of by the GST Council, serving as one of the pillars of fiscal federalism. State Governments accepted a significant reduction in their fiscal autonomy for implementing GST. In a significant recent verdict[14], the Hon’ Supreme Court held that the recommendations of the GST council are not binding on the Union and the State Governments. Hon’ Supreme Court observed that the Parliament intended that the recommendations of the GST Council will have persuasive value and both the Parliament, and the State Legislatures can equally legislate on GST. (Civil Appeal No. 1390 of 2022 dated 19/05/2022)

The Fifteenth Finance Commission[15] (XVFC) led by Chairman Shri N K Singh, recently submitted its Report for the period 2021-22 to 2025-26 to President of India. The share of states in the central taxes for the 2021-26 period is recommended at 41 percent. The adjustment of 1% is to provide for the newly formed union territories of J&K and Ladakh from the resources of the centre. The 15th FC has taken into account- income distance, area, population in 1971 & 2011, demographic performance, forest cover and ecology, tax and fiscal effort (to reward states with higher tax collection efficiency). One significant issue flagged by the XVFC is that salary income accounted for about 59 per cent of the declared incomes in the personal income tax segment, while only 27 per cent was business income (p-134).

The Union government generally collects 60-68% of combined revenue receipts due to buoyant and broad-based taxes assigned to it and the states together collect the balance. The revenue expenditure of the states, on the other hand, has been in the range 50-60% of the combined revenue expenditure[16]. This report[17] has also observed that the balance in Indian fiscal system has steadily but significantly shifted in favour of states over the years. Attempts should be made in future to examine questions regarding relative efficiency in delivery of public services amongst states. (p-98)

The financial supremacy allowed to the Centre may not be unreasonable. The favourable position given to the Centre regarding financial resources reflects the strong-centre theme running through the Constitution and many feel that this has been an important factor in keeping the country united[18].

[Note- The views/opinion expressed in the article are the personal opinion of the author and it should not be taken as the official view].

(CHANDRA PRAKASH BHATIA),

Additional Commissioner of Income Tax, Kolkata.

[1] P. J. Thomas, the Growth of Federal Finance in India: Being a Survey of India’s Public Finances from 1833 to 1839. London: Humphrey Milford, Oxford University Press, 1939, p. 12)

[2] India’s First Budget and the Birth of Income Tax- by the author, Renaissance Pub, Kolkata, 2015

[3] Speeches, Papers, &c. Connected with the Proposed Income- Tax, and The Recall of Sir Charles Edward Trevelyan, by William Thomas, Madras, 1860, p-62

[4] India’s Financial Statements 1860-61 to 1873-74

[5] 80 Years of Odisha Budget-A Commemorative Volume, Published by Government of Odisha

[6] India’s Financial Statements 1860-61 to 1873-74

[7] The Evolution of Provincial Finance in India- B R Ambedkar, P S King & Sons, Westminster, 1923

[8] Financial Resolution No. 3334 dated 14th December 1870

[9] Strachey, Sir John & Lt. Gen Richard, Finances and Public Works of India, Kegan, Paul, Trench & Co. (1882)

[10] The Evolution of Provincial Finance in India- B R Ambedkar, P S King & Sons, Westminster, 1923

[11] Indian Provincial Finance, 1919-39, By B R Misra, Humphry Milford, Oxford University Press, London, 1942

[12] The Servant of India. Vol IX, No. 13, April 29, 1926 pp. 163-64)

[13] Constituent Assembly Debates (Proceedings), Dated 22nd Nov 1949 – Vol- XI

[14] <http://scourtapp.nic.in/supremecourt/2020/23083/23083_2020_4_1501_35969_Judgement_19-May-2022.pdf>

[15] <https://fincomindia.nic.in/WriteReadData/html_en_files/fincom15/Reports/XVFC%20VOL%20I%20Main%20Report.pdf>

[16] <https://fincomindia.nic.in/writereaddata/html_en_files/fincom15/StudyReports/Resource%20sharing%20between%20Centre%20and%20States%20and%20allocation%20across%20States.pdf>

[17] <https://fincomindia.nic.in/writereaddata/html_en_files/fincom15/StudyReports/Resource%20sharing%20between%20Centre%20and%20States%20and%20allocation%20across%20States.pdf>

[18] Administrative Reforms Commission, 1968, p.15).