Abstract

Climate change is one of the most compelling global challenges. Hence, there is a call for urgent climate actions. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Special Report (October 2018) informed that it is still possible to limit climate change to 1.5°C if—and only if—there are rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society. So, considering this warning, UN Secretary General has asked to ramp up climate actions worldwide.

India, like other developing countries, is suffering the brunt of climate change. This paper examines analytically India’s climate actions despite the economic imperatives. Also, the scope, scale and speed of international climate finance arena which are lagging behind considerably. India, despite accounting for 18 percent of world’s population, uses only around 6 percent of the world’s primary energy. Energy poverty has been more pervasive in India than income poverty: 53 percent of India’s population did not have access to clean cooking in 2017. India is prone to natural climate variabilities. India’s NDC was not based on any temperature goal but was on a “best effort” basis, keeping in mind the developmental imperatives of the country.

The commitments made by the developed countries for enhancement and support in relation to climate finance as mandated in the UNFCCC and its Paris Agreement are not clearly translated into reality. The means to achieve the climate goals is not commensurate to the urgency shown, nor there is any seriousness in the discourse on climate finance. The Summary Report of the Standing Committee on Finance of UNFCCC (2018) outlines a picture, where it was indicated that total climate specific finance flows from Annex II Parties in 2016, amounts to around US$ 38 billion, which is less than 40 percent of the US$ 100 billion per year target of climate finance. Clearly, the commitments and the ensuing actions over the years have not even attained a tangential relationship.

India, as a responsible nation, will endeavor to do its best for adaptation and mitigation actions, keeping in mind the imperatives of sustainable development and poverty eradication. But in order to respond to the worldwide call for stepping up climate actions, it will have to be matched with adequate provision of means of implementation to developing countries. Climate finance is a key pillar in enabling climate actions. Enhanced ambition and enhanced support should be at equal footing. So, a serious discourse on means of implementation is required to take climate actions effectively.

Foreword

Action towards climate change is an undeniable concern for humanity and it is our responsibility to address it by using all means and wherewithal at our disposal.

India has been taking several proactive climate actions to fulfill its obligations as per the principles of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities and equity. The Earth’s carbon system is one of the global commons, and any discussion on the use of the commons by a group or community is by definition a collective action issue. What one country does or has to do, depend not only on itself but also on the response of others. For India, like all other nations, carbon space is a strategic asset and getting its fair share of carbon space, while being a responsible global player, taking concerted action in protecting the planet, is an important goal. India is steadily pursuing the imperative of diversifying energy supply, substantially increasing the share of non-fossil fuel energy in the total energy mix and enhancing the use of energy conservation technologies and practices.

Amidst growing developmental challenges, India is sustainably managing its natural resources while adhering to the principle of sustainable production and consumption. India has proactively pursued mitigation and adaptation activities and achieved a reduction in emission intensity of GDP by 21 percent over the period 2005-2014.

In the background of the UN Secretary General’s call to ramp up climate actions worldwide, resonated with the release of the recent IPCC 1.5°C report, the attached Discussion Paper makes an analysis of post Paris Agreement developments and suggests that much more work needs to be done to meet its targets which are contingent on the momentum in international climate finance arena, enhanced new, additional and climate specific financial, technological and capacity building support and the scope, scale and speed of climate finance as they are lagging behind considerably.

The global action on climate change is subject to the delivery of timely and adequate finance. The worldwide call for stepping up climate actions will have to be matched with adequate provision of climate finance to developing countries. Global climate action rests on the shoulders of the means of implementation, especially on finance and technology and there is a need to solve this problem urgently. I hope that this Reflection paper will be of utility to stakeholders during deliberations in the UN Climate Action Summit which will be held on 23 September, 2019 in New York.

Secretary, Department of Economic Affairs

17 September, 2019

Climate Summit for Enhanced Action: A Financial Perspective from India

1. Introduction

On 23 September, 2019, the Secretary-General of the United Nations António Guterres will host the Climate Action Summit in New York. His precise call to all leaders of the world is to come to New York with concrete, realistic plans to enhance their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) by 2020, in line with reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 45 percent over the next decade to net zero emissions by 2050. His quote on record is that, “I want to hear about how we are going to stop the increase in emissions by 2020, and dramatically reduce emissions to reach net-zero emissions by mid-century”. His request, in essence, is to enhance emission reduction targets to what Nations have already agreed under the Paris Agreement in the form of NDCs.

1.2 Having the key focus on raising ambition and accelerate action to implement the Paris Agreement, the Climate Action Summit focuses on nine interdependent tracks, which are led by 19 countries in total and are supported by international organizations. The Summit is expected to bring together governments, the private sector, civil society, local authorities and other international organizations to develop ambitious solutions in actionable areas. The Secretary-General has also prioritized a number of action portfolios. The key areas identified are the following:

- Finance: mobilizing public and private sources of finance to drive decarbonization of all priority sectors and advance resilience;

- Energy Transition: accelerating the shift away from fossil fuels and towards renewable energy, as well as making significant gains in energy efficiency;

- Industry Transition: transforming industries such as oil and gas, steel, cement, chemicals and information technology;

- Nature-Based Solutions: reducing emissions, increasing sink capacity and enhancing resilience within and across forestry, agriculture, oceans and food systems, including through biodiversity conservation, leveraging supply chains and technology;

- Cities and Local Action: advancing mitigation and resilience at urban and local levels, with a focus on new commitments on low-emission buildings, mass transport and urban infrastructure; and resilience for the urban poor;

- Resilience and Adaptation: advancing global efforts to address and manage the impacts and risks of climate change, particularly in those communities and nations most vulnerable.

- Mitigation Strategy: to generate momentum for ambitious NDCs and long-term strategies to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement.

- Youth Engagement and Public Mobilization: to mobilize people worldwide to take action on climate change and ensure that young people are integrated and represented across all aspects of the Summit, including the six transformational areas.

- Social and Political Drivers: to advance commitments in areas that affect people’s well-being, such as reducing air pollution, generating decent jobs, and strengthening climate adaptation strategies and protect workers and vulnerable groups.

1.3 To the question on why this Summit will be held in September 2019, the answer from UN is, “The latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report tells us that it is still possible to limit climate change to 1.5°C if—and only if—there are rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society. According to the same report, time is short and ambitious action must be ramped up now if we are to reach the 1.5°C goal”. But greenhouse gas emissions are continuing to rise to unprecedented levels and the impact of climate change is being felt on all the continents. The Climate Action Summit will ask leaders to demonstrate their leadership and increase ambition.

1.4 The UN Secretary General (UNSG) expects that the Summit will result in commitments by all participants to address climate change, which will be captured in a summary by the Secretary-General at the end of the Summit, which in turn is expected to guide/feed into the negotiations at COP-25 at Santiago de Chile, from 2 to 13 December 2019.

1.5 A global preparatory meeting for the Climate Action Summit was also held on 30 June -1 July 2019 in Abu Dhabi. The need to ratchet up the targets for mitigation, adaptation and climate finance was raised in this meeting.

2. Finance in Climate Treaties and COP Decisions

2.1 From Rio to Cancun:

2.1.1 The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was adopted at the “Rio Earth Summit” in 1992. The UNFCCC mandates that Parties should protect the climate system for the benefit of present and future generations of humankind, on the basis of equity and in accordance with their common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities. Accordingly, the developed country Parties should take the lead in combating climate change and the adverse effects thereof. The Convention noted that the largest share of historical and current global emissions of greenhouse gases has originated in developed countries, that per capita emissions in developing countries are still relatively low and that the share of global emissions originating in developing countries will grow to meet their social and development needs. Specifically, Article 4.4 mandates that the developed country Parties and other developed Parties included in Annex II shall also assist the developing country Parties that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change in meeting costs of adaptation to those adverse effects. Further, Article 4.5 mandates the developed country Parties and other developed Parties included in Annex II to take all practicable steps to promote, facilitate and finance, as appropriate, the transfer of, or access to, environmentally sound technologies and know-how to other Parties, particularly developing country Parties, to enable them to implement the provisions of the Convention.

2.1.2 The Article 4.7 of the UNFCCC makes it very clear- “The extent to which developing country Parties will effectively implement their commitments under the Convention will depend on the effective implementation by developed country Parties of their commitments under the Convention related to financial resources and transfer of technology and will take fully into account that economic and social development and poverty eradication are the first and overriding priorities of the developing country Parties”. Any mitigation action by the developing countries must, therefore, be taken in the context of sustainable development along with their national priorities. The Convention has defined a financial mechanism under its Article 11, the provision of financial resources on a grant or concessional basis, including for the transfer of technology.

2.1.3 To further strengthen the global response to climate change, the Parties to the UNFCCC adopted the Kyoto Protocol in 1997 which entered into force on 16 February 2005. It commits developed country Parties by setting internationally binding emission reduction targets, thereby placing more responsibilities on the developed nations under the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities.” It also recognized that the developed country Parties and other developed Parties included in Annex II to the Convention shall provide new and additional financial resources to meet the agreed full costs incurred by developing country Parties in advancing the implementation of existing commitments.

2.1.4 Kyoto Protocol introduced market mechanisms where carbon credits can be traded and sold to meet a part of emission reduction targets by countries. The Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), a market mechanism, defined in Article 12 of the Kyoto Protocol, allows a country with an emission-reduction or emission-limitation commitment by implementing an emission-reduction project in developing countries. Such projects can earn saleable certified emission reduction (CER) credits, each equivalent to one tonne of CO2, which can be counted towards meeting Kyoto targets. The mechanism stimulates sustainable development and emission reductions in developing countries, while giving industrialized countries some flexibility in how they can meet their emission reduction or limitation targets.

2.1.5 At the 13th session of Conference of Parties (COP-13) to the UNFCCC in 2007, Bali Action Plan was launched which was a comprehensive process to enable the full, effective and sustained implementation of the Convention through long-term cooperative action. It categorically stated that nationally appropriate mitigation actions by developing country Parties be supported and enabled by technology, financing and capacity- building and improved access to adequate, predictable and sustainable financial resources and technical support and the provision of new and additional resources, including official and concessional funding for developing country Parties. Bali Action Plan also placed emphasis on supporting urgent implementation of adaptation actions, taking into account the urgent and immediate needs of developing countries that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change. Climate finance was a key pillar in Bali Action Plan, emphasizing enhanced action on the provision of financial resources and investment to support action on mitigation and adaptation and technology cooperation.

2.1.6 At Copenhagen in 2009 (COP-15), climate finance was quantified in order for developing countries to scale up their mitigation actions and a flow of US$ 100 billion a year by 2020 by the developed countries was mooted. In Copenhagen, developed countries also committed to US$ 30 billion fast start financing (2010-2012) for adaptation and mitigation in developing countries. Further, it was decided to set up a dedicated Green Climate Fund (GCF) to provide support to developing countries by assisting them in mitigating climate change and adapting to its impacts. The Cancun Agreements adopted in 2010 (COP-16) constituted a set of significant decisions which included finance as a key category and committed to mobilize and provide scaled-up funds in the short and long term to enable developing countries to take greater and effective action. It also formalized the setting up of the GCF. Cancun decisions resulted in Cancun pledges and many countries submitted their plans for controlling greenhouse gas emissions. While Industrialized countries presented their plans in the shape of economy-wide targets to reduce emissions, mainly up to 2020, developing nations proposed ways to limit their growth of emissions in the shape of plans of action with appropriate and adequate support from industrialized countries in the form of technology cooperation, finance and capacity building.

2.2 From Durban to Paris – Agreeing on post 2020 climate actions

2.2.1 The COP-17 at Durban in 2011 recognized the need for a comprehensive plan after 2020 towards achieving the ultimate objective of the Convention. COP-17 decided to launch a process to develop a protocol, another legal instrument or an agreed outcome with legal force under the Convention applicable to all Parties and complete this process by COP-21. The negotiations under the Durban platform also encompassed finance and technology to assist developing countries in their climate actions.

2.2.2 The process was concluded at COP-21 in Paris in December 2015 in which a new Agreement in the shape of a treaty was adopted under UNFCCC to enhance the implementation of the Convention, including its objective. The Paris Agreement, the treaty, brought all nations to undertake ambitious efforts to combat climate change and adapt to its effects in the context of sustainable development and efforts to eradicate poverty. The Paris Agreement’s central aim is to strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change by keeping the global temperature rise this century well below 2° Celsius above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase even further to 1.5o Celsius. It states that “The Agreement will be implemented to reflect equity and the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities, in the light of different national circumstances.” The Paris Agreement requires all Parties to put forward their best efforts through NDCs and to strengthen these efforts in the years ahead.

2.2.3 The Article 9 of the Paris Agreement pertaining to climate finance stipulates that developed countries shall provide financial resources to developing countries and as part of the global effort, developed country Parties should continue to take the lead in mobilizing climate finance and noted the significant role of public funds taking into account the needs and priorities of developing country Parties. In its Article 9 (para 5) the Agreement states that developed country Parties shall biennially communicate indicative quantitative and qualitative information related to projected levels of financial resources to be provided to developing country Parties. Also, Article 9 (para 7) stipulates that developed country Parties shall provide transparent and consistent information on support for developing country Parties provided and mobilized through public interventions biennially. The Agreement also provides for enhanced transparency of action and support through a transparency framework.

2.2.4 The adoption and subsequent entry into force of the historic Paris Agreement was hailed by many. However, all that agreed regarding climate finance, in the Paris decision text (decision 1/CP.21, paragraph 53) was that, developed countries continue their existing goal of US$ 100 billion annually through 2025 and a new collective quantified goal from a floor of US$ 100 billion per year be set in 2025 taking into account the needs and priorities of developing countries.

2.3 Katowice Outcomes – Paris Agreement Work Programme.

2.3.1 At Katowice (CoP-24), in December 2018, new rules of accounting and a framework for climate finance was agreed upon under the Paris Agreement Work Programme (PAWP). Katowice finance decision came out with rules governing climate finance – the identification of ex ante information to be provided by developed countries in accordance with Article 9 (para 5); ex post information on financial support provided and mobilized under Article 9 (para 7) of the Paris Agreement respectively. Major outcomes also included transparency framework, global stocktake and facilitating implementation and compliance mechanisms. Finance outcome stressed on greater granularity in reporting including type of sectors for which support is provided, type of financial instruments etc. However, it was just a step forward and in fact the outcome was effectively more in favour of developed countries with the wordings such as “as available”, “an indication” with regard to projected levels of financing and of new and additional resources respectively. Even financial instruments such as loans, equity can be counted as climate finance and they are asked to report the grant equivalence on a voluntary basis only.

2.3.2 As far as the new collective quantified goal on finance in the Katowice decision is concerned, Parties agreed to initiate in November 2020, “deliberations on setting a new collective quantified goal from a floor of US$ 100 billion per year, in the context of meaningful mitigation actions and transparency of implementation and taking into account the needs and priorities of developing countries”. In effect, Katowice decision did not launch a process on setting a new collective quantified goal on finance, that takes into account their needs and priorities from a floor of US$ 100 billion per year, instead it is just limited to initiating the deliberations.

2.3.3 Paris Agreement, in fact, had provided an opportunity to agree on new rules of accounting and reporting framework for climate finance. Katowice outcome was expected to improve the acceptability of the reported numbers. In contrast, the long-standing demand of developing countries for ensuring clarity in international climate finance flows through a definition of climate finance was not delivered in Katowice. International community must understand that international public finance flows have strong linkages with implementation of developing country NDCs.

2.3.4 While Paris Agreement established clear linkages of implementation of NDCs, enabled through means of implementation, Katowice outcomes has taken it forward with transparency framework and compliance mechanism instead of strong means of implementation linkages. The transparency framework requires uniform reporting requirements on developed and developing countries, which would kick-start in 2024. In short, Katowice outcome on finance is just a step forward.

2.4 Talanoa Dialogue

2.4.1 In Paris at COP-21, it was decided to convene a Facilitative Dialogue among Parties in 2018 to take stock of the collective efforts of Parties. The objective of the Dialogue was to take stock of the progress of climate action since the adoption of Paris Agreement and to inform the next round of NDCs with a view to raise climate ambition. The design of the Dialogue is known as Talanoa Dialogue, which is a pacific tradition of holding conversation in an inclusive and receptive way. The three guiding questions for the Talanoa Dialogue were: Where we are? Where do we want to go? How do we get there? At Katowice, the “Talanoa Call for Action” was adopted. It states that pre-2020 action is vital for putting the world on a path towards achieving the long-term goals of the Paris Agreement. It also called upon governments and international agencies to step up financial, technical and technological cooperation. Talanoa Call for Action concluded by calling upon everyone to act with urgency and recognize that we are in a race against time – we must act now to ensure sustainable development and the preservation of life on earth as we know it.

3. Climate Finance Delivery – A Reality Check

3.1 Under the UNFCCC, the intent and obligation of climate finance is unambiguous, that developed country Parties shall provide financial resources to developing countries. Climate finance should support both the adaptation and mitigation activities of developing countries in accordance with the country needs and priorities. The Paris Agreement also gives equal weightage to adaptation and mitigation. While the Convention laid out the responsibilities between developed and developing countries in regard to finance, it was not possible to indicate the size or quantum of finance at that stage. The magnitude and enormity of climate finance requirements, however, were recognized in various studies and has been an integral part of climate change discourse. This led to a decision in Copenhagen in 2009 which stated that “developed countries commit to a goal of mobilizing jointly US$ 100 billion a year by 2020 to address the needs of developing countries” and “a significant portion of such funding should flow through the Copenhagen Green Climate Fund.”

3.2 To get a sense of the actuals, Summary Report of the Standing Committee on Finance of UNFCCC (2018) outlines a picture, where it was indicated that total climate specific finance flows from Annex II Parties in 2016, amounts to around US$ 38 billion which is less than 40 percent of the US$ 100 billion target of climate finance. Out of the total finance flows, US$ 30 billion in 2015 and US$ 34 billion in 2016 were reported as climate-specific finance channeled through bilateral, regional and other channels; the remainder flowed through multilateral channels. The report also mentions aggregate flows for mitigation remains greater than support for adaptation across all sources. Adaptation received only 29 percent and 25 percent of the bilateral fund flows and multilateral fund flows respectively during 2015-16. It also stated that during same period, only 9 percent of adaptation finance flowing through multilateral development banks (MDBs) was grant based. The report confirms the level of climate finance is considerably below what one would expect given the opportunities and needs that have been identified. Clearly, the commitments and the ensuing actions over the years have not even attained a tangential relationship.

3.3 In contrast, the total pledges to the GCF, the largest dedicated climate fund as on July’ 2019 are a meagre US$ 10.3 billion. An analysis of the GCF Fund status, after its operationalization, shows that out of US$ 10.3 billion pledged, US$ 7.23 deposited, US$ 4.60 approved and amount disbursed is US$ 0.39 billion (Figure 1).

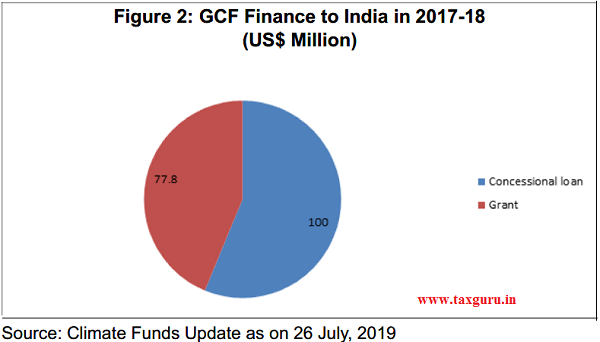

3.4 The GCF Finance to India as per the latest available information amounts to only US$ 177 million, out of which only US$ 77.8 million is grant based finance (Figure 2). For the developing countries, the estimated costs for implementing NDCs would be much over US$ 4 trillion. These funds would, if the current trend prevails, fall drastically short of developing countries’ requirements. Further, the GCF is now facing withdrawal of some earlier promised sums and replenishment discussions: that GCF is yet to reach a meaningful stage. The Global Environment Facility (GEF), another operating entity of financial mechanism of UNFCCC, financed about US$ 5.6 billion in last 27 years for mitigation. GEF funding has been decreasing as a share of climate change (Figure 3).

3.5 To answer the question of whether the speed of climate finance in the multilateral climate regime is sufficient, we need to know whether the developed countries have fulfilled their commitments and the progress of delivery of finance from developed to developing countries.

3.6 As per latest data available of Climate Funds Update, the actual pledges from developed to developing countries for climate finance is around only US$ 30 billion, whereas deposits and approval are around US$ 26 billion and US$ 19 billion respectively (Figure 4).

3.7 In 2015, developed countries published a roadmap to US$ 100 billion, which claimed that public climate finance levels had reached US$ 41 billion per year in 2013-14. However, these claims have been contested by many. Firstly, there are various issues in reporting i.e credibility, accuracy and fairness. A Government of India Discussion Paper in 2015 noted that only credible number is US$ 2.2 billion in 2013-14, if we restrict to country disbursements of actual climate finance on a concessional basis from 17 special climate change multilateral, bilateral and MDB funds created for the specific purpose. There were serious concerns raised in the methodologies of accounting especially the definitional requirements of “new and additional” and grant equivalent elements. This needs improvement. A road map to raise climate change finance is urgent and a must for implementing NDCs. Only then, climate justice, for poorer countries and future generations, can be delivered.

3.8 Oxfam (2018) provided an assessment of US$ 100 billion goal that states, the aggregated climate finance, estimated as net climate-specific assistance, is far lower than the reported climate finance and the new climate-specific assistance may be just US$ 16-21 billion. The value of loans is being over-reported. If the finance for development projects that only partially cover climate change were reported more accurately, annual bilateral flows of public climate finance could be between US$ 10 billion and US$ 15 billion lower than reported. Grant based assistance is low and is rising too slowly; only an estimated US$ 11-13 billion was given as grants per year, forming just 23-27 percent of the total, public climate finance amounted to 21 percent of total global official development assistance (ODA) budgets in 2015-16. The key takeaway here is that international community, unfortunately, will need to worry about the gross finance gap which exists for successful implementation of NDCs. Without sufficient finance, none of the other components of ambition which we hear in the discourse of climate change will fructify.

4. 3 Essential ‘S’s of Climate Finance- Scope, Scale and Speed

4.1 As argued in the above sections, availability of finance no doubt is the key pillar in enabling climate actions. This brings to the deliberations for understanding the 3 essential “S”s of Climate Finance – Scope, Scale and Speed for global cooperative action against climate change.

4.2 The UNFCCC and its Paris Agreement clearly mandates developed countries to provide financial resources to developing countries for taking climate actions. But what constitutes these financial resources for climate finance itself, its key elements, are only very broadly defined, which provides discretion to developed countries regarding climate finance accounting. Each developed country could decide what it counts as climate finance and why it is climate finance and whether it can be considered as “new and additional” (Romain Weikmans & J. Timmons Roberts, 2017).

4.3 The essential elements that need to be taken up as parameters for accounting climate finance are – public grants, unrequited equity and grant-equivalent values of loans and actual disbursements of such finance crossing borders in a particular year.

4.4 For developing countries with their myriad developmental challenges and scarce resources, climate change puts an additional burden, though their contribution to the cause of climate change is minimal. Even preliminary estimates by simply summing the finance needs in NDCs with a conditional component, comes to around US$ 4.4 trillion (Weischer et al., 2016). A recent report by Oxfam (2018) indicated, “People in poorer countries are on average five times more likely than people in rich countries to be displaced by extreme weather events. Adaptation costs in developing countries are expected to be US$ 140- 300 bn a year by 2025/ 30. By mid-century, the costs of climate change to developing countries are estimated to exceed US$ 1 trillion per year, even if global average temperature remains below 2°C.”

4.5 As regards finance needs in Indian NDC, it states, preliminary estimates indicate that India would need around US$ 206 billion (at 2014-15 prices) between 2015 and 2030 for implementing adaptation actions in key areas like agriculture, forestry, fisheries, infrastructure, water resources and ecosystems. Apart from this, there will be additional investments needed for strengthening resilience and disaster management. NDC further provides the preliminary total estimates for meeting India’s climate change actions between 2015 and 2030 which is at US$ 2.5 trillion (at 2014-15 prices). The International Finance Corporation in its 2017 report on “Climate Investment Opportunities in South Asia” estimates that a US$ 3.4 trillion climate investment opportunity will arise in South Asia in key sectors between 2018 and 2030, assuming that each country will fully meet its NDC. Of this, US$ 3.1 trillion worth of investment opportunity will be presented by India alone due to the scale of its economy and population.

4.6 Another reality of the climate finance pledges is the skewed preference towards mitigation projects than adaptation. It needs to be stressed that more focus is required to be given on adaptation actions by the developing countries and moreover, these need to be primarily financed by public resources. The primary imperative for developing countries is adaptation. Even the Adaptation Fund has pledged less than US$ 1 billion as of today, a reality which is no less than harsh truth.

4.7 It is evident from the above analysis that the recent estimates for taking climate actions are laying out a case for trillions and not billions, in new and additional financing. The Copenhagen goal of US$ 100 billion in climate change finance flows annually by 2020 will have to be fulfilled in concrete terms in a credible manner. The US$ 100 billion is a modest number in contrast to the actual requirements. Moreover, there will arise a need for more scrutiny of climate finance as more granularity in the data becomes available. This will also be helpful in global stocktake in 2023. The 3 Essential ‘S’s of climate finance are important inputs to be taken into account in the global stocktake. A roadmap to raise climate change finance from the floor of US$ 100 billion to match the three essential ‘S’s of climate finance- Scope, Scale and Speed is an urgent and a fair ask by developing countries to deliver climate justice.

5. India’s Climate Actions despite Economic Imperatives

5.1 Juxtaposed between the Himalayas and the India ocean, the sub-continent of India is subject to much higher climate variability, both spatial and temporal as compared to continental climates of North America and Europe. India’s climate ranges from extremes of heat to extremes of cold, from extreme aridity and negligible rainfall to excessive humidity and torrential rainfall. The rainfall in India shows great variation, unequal seasonal and geographical distribution and frequent departures from the normal. Temperature variations are also notable in the Indian sub-continent. Its annual mean, maximum and minimum temperatures during the period 1901-2010, show a significant increasing trend of 0.60°C, 1.0°C and 0.18°C per hundred years, respectively. Daily rainfall observations during the period 1901-2004 indicate that the frequency of extreme rainfall events (rain rate > 100 mm/day) has a significant positive trend of 6 percent per decade. Hence, India has recognized the global challenge of climate change and demonstrated its share of responsibility in terms of national policies and programmes and implementing climate actions through improving efficiency of the economy and its engines of growth.

5.2 Launched in 2008, India’s National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC) identifies a number of measures that simultaneously advance the country’s development and climate change related objectives of adaptation and mitigation. The implementation of NAPCC is designed to take place through focused National Missions, which form the core of the National Action Plan and incorporate multi-pronged, long-term and integrated strategies for achieving India’s key goals in the context of climate change. It was also meant to focus on key adaptation requirements and creation of scientific knowledge and preparedness for dealing with climate change. For the realization of these proposed actions at the sub national level, State Action Plans on Climate Change (SAPCC) consistent with strategies in the NAPCC were prepared. In 2009, in Copenhagen, India has promised to reduce its emission intensity of GDP by 20 to 25 percent from 2005 levels by the year 2020. The outcomes of these various initiatives resulted in reduction of India’s emission intensity of GDP by 21 percent between 2005 and 2014 and its achievement of climate goal for pre-2020 period is on track.

5.3 The broad policy framework of NAPCC and SAPCC, had their influences in preparing the NDC targets. NDC being the bedrock for climate actions addresses all aspects -Adaptation, Mitigation, Finance, Technology Transfer, Capacity Building and Transparency of Action and Support. In its NDC, India had promised to reduce its emissions intensity of GDP by 33 to 35 percent below 2005 levels by the year 2030. India also promised to ensure that 40 percent of cumulative electric power installed capacity would be from non-fossil fuel sources by 2030 and increase its forest cover and additional carbon sink equivalent to 2.5 to 3 billion tons of carbon dioxide by 2030. It is important to state that India’s NDC was not based on any temperature goal but was on a “best effort” basis, keeping in mind the developmental imperatives of the country. India’s NDC clearly states – “keeping in view its development agenda, particularly the eradication of poverty coupled with its commitment to following the low carbon path to progress and being sanguine about the unencumbered availability of clean technologies and financial resource from around the world, India communicates its Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC)”. It was developed envisaging the availability of international public finance for climate finance, based on the objectives of effective, cooperative and equitable global architecture based on climate justice and the principles of equity and common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities. It also recognizes that poverty eradication is the overriding priority for India. Hence, the implementation of the climate targets is not exclusive of the global and national economic scenario.

5.4 To achieve the objective of becoming a US$ 5 trillion economy by 2024-25, India needs to sustain a real GDP growth rate of 8 percent. International experience, suggest that such growth can only be sustained by a “virtuous cycle” of savings, investment and exports catalyzed and supported by a favorable demographic phase. Given India’s development agenda, the infrastructure deficit represented by different indicators, the pressures of urbanization and industrialization and the imperative of sustainable growth, India faces a formidable and complex challenge in working for economic progress towards achieving a secure future for its citizens.

5.5 India, very well understands that energy is vital for development and prosperity of any economy, however, it lags behind significantly in energy usage. Despite accounting for 18 percent of world’s population, India uses only around 6 percent of the world’s primary energy. India’s per capita energy consumption equals 0.6 tons of oil equivalent (toe) as compared to the global per capita average of 1.8 toe. India’s per capita primary energy consumption lags that of the upper-middle-income countries by a considerable margin (Figure 5). Energy poverty has been more pervasive in India than income poverty: 53 percent of population did not have access to clean cooking in 2017. Energy intensity of India’s GDP has been declining in the recent past, which is reflective of increase in the efficiency of energy use. To achieve per capita GDP comparable to that of the upper-middle-income countries, India requires greater energy resources and that too at a rapidly increasing rate. Only with an assured increase of per capita energy consumption by 2.5 times, India will be able to increase its real per capita GDP to US$ 5000 (in 2010 prices).

5.6 Access to energy is important not just in its own right but also due to its linkages with various social indicators. This is highlighted by the strong relationship between Human Development Index (HDI) and per capita energy consumption (Figure 6). At low levels of energy consumption, increases in per capita energy consumption leads to considerable increases in human development. The curve fitted to the data indicates that for countries in the sub 100 Gigajoules per capita energy consumption region, small increases in energy consumption correspond to large increases in HDI. A country with 100 Gigajoules of per capita energy consumption, on an average, has HDI of around 0.8 which is considered to be very high. India had a per capita energy consumption of 24 Gigajoules and HDI of 0.64 in 2017 i.e., medium human development. India would have to quadruple its per capita energy consumption to reach a HDI of 0.8 and enter the group of countries with high human development.

5.7 India has always strived to ensure that it follows a growth path that delivers sustainable development and protect the environment. The implementation of various energy efficiency programmes has witnessed exceptional performance in terms of reducing energy consumption thereby leading to lower greenhouse gas emissions. The overall electricity savings due to energy efficiency measures is 7.21 percent of the net electricity consumption in 2017-18, total thermal energy saved is 2.7 percent of the net thermal energy consumption and 2.0 percent of the net energy supply. It also contributed in reducing 108.28 million tons of CO2 emission.

5.8 Even as climate change becomes more palpable, India is fighting hard for achieving its goals under the Paris Agreement by investing in various schemes aligned with its NDC, like Clean India Mission, National Smart Grid Mission, Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation etc. Notwithstanding the economic actualities, India’s mitigation strategies have emphasized on clean and efficient energy system, enhanced energy efficiency in industries, resilient urban infrastructure as well as safe, smart and sustainable green transportation network. It has also laid importance to planned afforestation, as well as holistic participation across all the sectors. The year 2014-15 has seen a significant leap forward for renewable energy with India undertaking one of the world’s largest renewable energy expansion programmes in the world. The share of renewables (excluding hydro above 25 MW) in total generation was around 10 percent in the year 2018-19 as compared to around 6 percent in 2014-15. Now globally India stands 4th in wind power, 5th in solar power and 5th in renewable power installed capacity. The cumulative renewable power installed capacity (excluding hydro above 25 MW) has more than doubled from 35 GW on 31 March 2014 to 78 GW on 31 March 2019. In addition, around 27 GW renewable power capacity is under installation and over 38 GW under bidding. The target is to achieve an installed capacity of renewable based power of 175 GW by the year 2022.

5.9. Solar power installed capacity has increased around 1000 times from 25 MW as on 31 March, 2011 to 28.18 GW as on 31 March, 2019. Priority has been accorded to seamless integration of renewables into the grid and better grid stability. Achieving the National Solar Mission target of 1,00,000 MW by 2022 will require a total investment of around US$ 85.71 billion. Broad estimates suggest that an investment of around US$ 250 billion would be required for the period 2023-2030. Thus, on an annualized basis, investment opportunity for over US$ 30 billion per year is expected to come up for the next decade and beyond. To provide a fillip to the ambitious renewable energy targets, renewable purchase obligations have been imposed on Obligated Entities (DISCOMs, Open Access Consumers and Captive power producers) to purchase a minimum share of their electricity from renewable sources.

5.10 Under Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (launched on May 1, 2016) which aims to safeguard the health of women & children by providing them with a clean cooking fuel – LPG, more than 70 million connections have been given since its inception with the total reimbursement of about US$ 1.1 billion. In order to support poor families, Pradhan Mantri Sahaj Bijli Har Ghar Yojana – ‘Saubhagya’ was launched on 25 September, 2017 to provide free electricity connections to all the poor households. All villages, and almost 100 percent households across the country have been provided with electricity.

5.11 Coal is the most abundant fuel resource in India with a cumulative total reserve of nearly 307 billion tonnes. So, for making best use of coal, India has commenced the work on its first coal-gasification based fertilizer plant with pet coke blending in Talcher, Odisha with an estimated investment of about US$ 1.85 billion and is targeted to be commissioned by 2022. Further development and scaling up of these green technologies require more international cooperation and participation.

5.12 Considering the large consumer base, India also aims to leapfrog and envision as a global hub of manufacturing of Electric Vehicles. With this view, a “National Electric Mobility Mission Plan 2020 (NEMMP)” and “Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Electric vehicles (FAME)” schemes were lunched to augment the sales of Electric Vehicle. FAME India Phase II has also been launched, with effect from 1 April 2019, with a total outlay of about US$ 1.4 billion over a period of three years.

5.13 India has also set up the National Investment and Infrastructure Fund (NIIF) in 2015 with US$ 6 billion (approx.) to provide long term capital for infrastructure projects. This was introduced to maximize economic impact through infrastructure development in viable projects. Another important area where India has made remarkable progress is Information and Communication Technology (ICT) sector, which enables sustainable development. India is emerging as the hub for “Digital Skills”. The country spends around US$ 1.6 billion annually on training workforce in the sector.

5.14 While the means of implementation pledged from the global community is not witnessing any sufficient momentum, the domestic imperatives of sustainable macroeconomic development face continuous crossroads for channeling the valuable yet limited resources. Hence, the best effort basis of India’s NDC is inherently taking into account the economic development imperatives.

6. Emergence of New “Priorities”, “Ambitions” and “Externalities” – New Asks

6.1 The UN Secretary General’s Climate Action Summit has a number of “new asks”. The call is for ramping up of climate actions worldwide; reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 45 percent over the next decade, and to net zero emissions by 2050. The logic for these “new asks” is explained as climate change is disrupting national economies, costing us dearly today and even more tomorrow and that affordable, scalable solutions are available now that will enable all to leapfrog to cleaner, more resilient economies. One among the nine interdependent tracks is climate finance and carbon pricing, which focuses on initiatives showcasing that making public and private finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development is possible and irreversible, and on delivering on commitments of providing US$ 100 billion annually by 2020 for mitigation and adaptation.

6.2 The “new asks”, in particular, net zero emissions mean a sweeping change across the entire economy, doing away with emissions. This can be a global aspirational goal and developed countries must be on track to take measures and legislate for net zero emissions by 2050. But it cannot be a goal for developing countries as the technologies have not progressed and aren’t all available yet for developing countries. And the past performance on both finance and technology front is just not reassuring for them.

6.3 It is also a bit disturbing to observe that some of the recent initiatives and discourse tend to put private sector finance on a higher pedestal. In reality, private sector is likely to invest in areas where returns are high and risks are low. Precisely for this reason, Article 9.3 of the Paris Agreement clearly noted the significant role of public finance. It is therefore essential to explore and finalize innovative instruments to supplement public finance such as interest subsidies, sovereign guarantees, and credit enhancement mechanisms. In addition, a recently emerging theme is the incorporation of climate risk in financial decision making. But we need to ensure that risk perception of the developing countries is not adversely impacted by any incorporation of climate disclosures and climate variables in risk management frameworks.

6.4 A great deal of stress is also being laid upon the inter-generational equity in regard to the emerging climate actions proposed to be taken by the present generation. However, the imperatives of the intra-generational equity, i.e. eradication of poverty and equitable social and economic development cannot be brushed-aside. And for any kind of equity, availability of adequate climate finance to developing countries for their climate actions is essential.

6.5 Worldwide call for stepping up climate actions was resonated with the release of the IPCC 1.5°C report (2018), which called for unprecedented actions to address climate change. Simultaneously, the IPCC Report also pointed out sharply that, “Limiting global warming to 1.5°C in the context of sustainable development and poverty eradication requires a portfolio of mitigation and adaptation actions that work across sectors and scales.” These actions would face key barriers and should be enabled by changes such as finance and technology. Global investment needs for both adaptation and mitigation are higher in most 1.5°C-consistent pathways compared to today, with an additional 1.7 percent to 2.5 percent of annual economy-wide investment required from the present to 2035. The report also says, “International funding and technology transfer can support fast and profound local transformation when they consider the context-specific needs of recipients”.

6.6 The recent ‘Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse gas fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems’ (IPCC August 2019) calls for better land management to tackle climate change and talked about the urgent need for more collective action to ensure the world’s forests, farms, and other landscapes are protected and developed in a sustainable way. Climate change increases the frequency and intensity of droughts, flooding and heat waves, which can irreversibly destroy natural ecosystems and lead to food shortages. Actions can be taken in the near-term, based on existing knowledge, to address desertification, land degradation and food security while supporting longer-term responses that enable adaptation and mitigation to climate change. These include actions to build individual and institutional capacity, accelerate knowledge transfer, enhance technology transfer and deployment, enable financial mechanisms, implement early warning systems, undertake risk management and address gaps in implementation and upscaling- the Report states. It will be a key scientific input into forthcoming climate talks. However, the momentum we see in international climate finance arena and the scope, scale and speed of climate finance is lagging behind considerably. Any significant efforts on climate finance arena are yet to be seen in the mobilization and global action on climate change is contingent on the delivery of timely and adequate finance. Call for climate actions should set in motion a serious discourse on climate finance required to take climate actions effectively.

7. Indian Response to Climate Emergency: Some Considerations

7.1 In the light of the factual narration above in the context of multilateral treaty provisions, the three essential ‘S’s – Scope, Scale and Speed – of climate finance, India’s climate actions, the next question is what should be the considerations to finalize India’s response?

7.2 NDC is the bedrock of India’s climate actions post 2020, which was submitted on a “best effort” basis, keeping in mind the developmental imperatives of the country. While depositing the instrument of ratification, India stated that “The Government of India declares its understanding that, as per its national laws; keeping in view its development agenda, particularly the eradication of poverty and provision of basic needs for all its citizens, coupled with its commitment to following the low carbon path to progress, and on the assumption of unencumbered availability of cleaner sources of energy and technologies and financial resources from around the world; and based on a fair and ambitious assessment of global commitment to combating climate change, it is ratifying the Paris Agreement”.

7.3 India will endeavor to do its best for its climate actions. The national circumstances demand that the first priority for India is adaptation, being a country highly vulnerable to extreme weather events. Climate change impacts are expected to worsen with the passage of time because of the momentum due to present carbon stock continuing to raise the temperature. Hence, India’s adaptation needs will have to be intensified and so the adaptation costs will increase. In short, enhancement of climate actions in the Indian context means more adaptation actions which would further require more resources to enable these actions. India is doing adaptation in mission mode. As examined above, India is doing the promised mitigation actions also in mission mode. However, finance still remains the critical issue. Despite the various climate finance decisions, there are attempts by some developed country Parties to shrug off even their modest past responsibilities. We are very far from the climate finance goals promised under various COP decisions. Yes, for ambitions to be set high; finance should be an integral part of it. Only then, climate justice can be delivered to the poorer countries. Denying the developing countries, their fair share in the atmospheric resource goes against all tenets of equity and the well-established principle of common but differentiated responsibilities.

7.4 Provision of technology also needs to be addressed parallelly which would further augment the demand for financial resources. IPCC Special Report (2018) states that “the systems transitions consistent with adapting to and limiting global warming to 1.5°C include the widespread adoption of new and possibly disruptive technologies and practices and enhanced climate-driven innovation. These imply enhanced technological innovation capabilities, including in industry and finance. Innovation policies may be more effective when they combine public support for research and development with policy mixes that provide incentives for technology diffusion. International cooperation is a critical enabler for developing countries and vulnerable regions to strengthen their action for the implementation of 1.5°C consistent climate responses, including through enhancing access to finance and technology and enhancing domestic capacities”. However, at this juncture, India is not aware about the availability of technology and finance and thus, can only aspire to implement its already promised climate actions and do equally well or better in comparison to economies with similar levels of development.

7.5 India aims for a US$ 5 trillion economy by 2024. As Hon’ble Prime Minister Modi put it, “Earlier, India was walking, but New India will be running.” This means massive infrastructure development in the country. A year before 2024 is the time when the global community will do first global stocktake under the Paris Agreement. This is the time, when India will be better placed to consider a mid-term assessment of its actions and suitably recalibrate through reexamination and improvement. For the present, India may only be in a position to elaborate or clarify its post 2020 climate actions already pledged in its NDC.

8. Conclusion

8.1 The message is very clear- a call for urgent climate actions. But this worldwide call for stepping up climate actions will have to be matched with adequate provision of climate finance to developing countries. Climate finance is a key pillar in enabling climate actions. Enhanced ambition and enhanced support should be at equal footing. It should take into account meaningful translation of developing country NDCs to concrete actions. In essence, the same urgency will have to be seen in the scope, scale and speed of climate finance, without which the world cannot achieve the objectives of the Convention and Paris Agreement. Considering this, call for action should set in motion a serious discourse on climate finance required to take climate actions effectively. As narrated above, the grave concern is the trend of developing countries being denied their right to financial resources for climate actions.

8.2 India, as a responsible nation, will endeavor to do its best for adaptation and mitigation actions, keeping in mind the imperatives of sustainable development and poverty eradication. As examined above, India is doing the promised adaptation and mitigation actions in mission mode. However, finance still remains the critical issue as India is stepping up its targets majorly by relying on domestic budgetary resources. Given this, India will be better placed to consider a mid-term assessment of its actions and suitably recalibrate through reexamination and improvement when the global stocktake takes place in 2023. For the present, India may only be in a position to elaborate or clarify its post 2020 climate actions already pledged in its NDC.

8.3 India is very well aware of that world needs to do much more than what they are currently committed to because the current promises are not enough. So, it is an important urge that all the developed countries must fulfill their prior commitments. In this respect, developed countries should enhance their support to developing countries for actions related to adaptation and mitigation. This must be done through adequate provision of finance, technology transfer, and capacity building to facilitate the effective implementation of the Convention and its Paris Agreement.

8.4 There is no time to lose as implementation of NDCs will have to be rolled out from 1.1.2021 which is only a little more than a year away. However, the reality is that the implementation of NDCs of developing countries will apparently hit a roadblock in the face of an uncertain future in the provisioning of climate finance. Under these circumstances, effectively addressing 3 “S” s of climate finance- Scope, Scale and Speed is necessary for having a realistic hope of achieving the objectives of the Convention, including the temperature goal of the Paris Agreement.

References:·

- Business Standard, September 24, 2018, “GAIL (India) update on India’s firstcoal gasification-based fertilizer plant at Talcher”, https://www.business-standard.com/article/news-cm/gail-india-update-on-india-s-first-coal-gasification-based-fertilizer-plant-at-talcher-118092400251_1.html·

- Climate Funds Update, August 2019, https://climatefundsupdate.org/data-dashboard/#1541245664232-8e27b692-05c8·

- Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 2015, “Roadmap to US$100 Billion”,https://dfat.gov.au/international-relations/themes/climate-change/Documents/climate-finance-roadmap-to-us100-billion.pdf·

- Economic Survey 2017-18 https://mofapp.nic.in/economicsurvey/economicsurvey/index.html·

- Economic Survey, 2018-2019, https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/economicsurvey/·

- Export.gov, 2019, “India – Information and Communication Technology”, https://www.export.gov/article?id=India-Information-and-Communication-Technology·

- Global Environment Facility, 2018, “Initial Gef-7 Star Country Allocations”, https://www.thegef.org/sites/default/files/publications/GEF-C.55-Inf.03-GEF-7-STAR.pdf·

- Global Environment Facility, August 2018, https://www.thegef.org/about/funding·

- Green Climate Fund, August 2018, https://www.greenclimate.fund/countries/india·

- Green Climate Fund, December 2017, “GEF-7 Replenishment Gef-7policyAgenda: Analysis in Support Of The Proposed Gef-7 Policy Recommendations”,https://www.thegef.org/events/gef-7-replenishment·

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 2018, “Global Warming of1.5 ºC”, https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/·

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 2019, “Special Report onclimate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management,food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems (SR2)”, https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/07/sr2_background_report_final.pdf·

- International Finance Corporation, 2017, “Climate Investment Opportunities inSouth Asia”, https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/fa3bea68-20f1-4cb4-90b9-3e812d38067f/Climate+Investment+Opportunities+in+South+Asia+-+An+IFC+Analysis.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CVID=l.raVua·

- Invest India, 4th September. 2019, https://www.investindia.gov.in/sector/it-bpm

- Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, 2019, “BASIC countriesto play an important role in making Paris agreement accepted in letter andspirit by the World: Union Environment Minister,” http://pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare. aspx?PRID=1582241

- Ministry of Finance, 2015, “Climate Change Finance, Analysis of a RecentOECD Report: Some Credible Facts Needed”, https://dea.gov.in/sites/default/files/ClimateChangeOEFDReport_0.pdf

- Ministry of Finance, PIB 22 January 2018, “National Investment andInfrastructure Fund (NIIF) makes its First Investment; NIIF has partnered withDP World to create an investment platform for ports, terminals, transportationand logistics businesses in India” https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=175796

- Ministry of Finance, 2018, “3 Essential “S”s of Climate Finance – Scope, Scaleand Speed: A Reflection”, http://ies.gov.in/pdfs/final-print.pdf

- Ministry of New and Renewable Energy, PIB, 17-June-2015, “Revision ofcumulative targets under National Solar Mission from 20,000 MW by 2021-22to 1,00,000 MW “, https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=122567

- Ministry of Petroleum & Natural Gas, PIB, 24-June-2019, “7.23 CroreConnections released under Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana”, https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=190670

- Ministry of Petroleum & Natural Gas, PIB, 17-August-2016, “7 Pradhan MantriUjjwala Yojana: A Giant Step Towards Better Life For All”, https://pib.gov.in/newsite/printrelease.aspx?relid=148971

- Ministry of Power, PIB, 31-December-2018,”2.39 crore households connectedsince the launch of Saubhagya scheme” https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=186988

- NITI Aayog, Coal Gasification in India, “https://niti.gov.in/writereaddata/files/Coal-Gasification-in-India-1.pdf”

- Oxfam, 2018, “Climate Finance Shadow Report 2018”, https://d1tn3vj7xz9fdh.cloudfront.net/s3fs-public/file_attachments/bp-climate-finance-shadow-report-030518-en.pdf

- Rajasree Ray & J M Mauskar (2018), “Climate finance: Myth vs. reality. BusinessStandard, November 17, 2018,” http://ies.gov.in/pdfs/climate-finance-myths.pdf

- Rajasree Ray & J M Mauskar (2019), “How to ramp up global climate financeflows,” http://www.ies.gov.in/pdfs/climate-finance.pdf

- Romain Weikmans & J. Timmons Roberts, 2017, “The international climatefinance accounting muddle: is there hope on the horizon?” https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource The%20international%20climate%20finance%20acctg%20muddle.pdf

- UN Climate Action Summit, 2019 https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/un-climate-summit-2019.shtml

- UNFCC, 2018, “Achievements of The Clean Development MechanismHarnessing Incentive For Climate Action” https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/UNFCCC_CDM_report_2018.pdf

- UNFCCC, 2015, “India’s Intended Nationally Determined Contribution”, https://nmhs.org.in/pdf/INDIA%20INDC%20TO%20UNFCCC.pdf

- UNFCCC, 2018, “Summary Report of the Standing Committee on Finance ofUNFCCC (2018)”, https://unfccc.int/scf

- Union Budget 2019-20, https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/

- Weischer et al., 2016, “Investing in Ambition Analysis of the financial aspects in(Intended) Nationally Determined Contributions:, https://www.deutscheklimafinanzierung.de/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Germanwatch-INDCs-and-finance.pdf+

Source- https://dea.gov.in/sites/default/files/FINAL%2017%20SEPT%20VERSION%20Climate%20Summit%20for%20Enahnce%20Action%20A4%20size.pdf