Case Law Details

Sekeleti Doris Vs Customs (Delhi High Court)

Delhi High Court, in the case of smuggling of Methaqualone denied the bail application since threshold of Section 37 of Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985 [NDPS Act] not having been crossed.

Facts- This application has been filed by applicant under Section 439, Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 read with Section 37, Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985 seeking regular bail in case arising out of criminal complaint dated 09th June 2022 by Air Customs Officer, Terminal-3, Indira Gandhi International Airport, New Delhi. Said complaint was filed before the Special Judge (NDPS), Dwarka Court, New Delhi to take cognizance of offences allegedly committed by the applicant under Sections 21/23/29 of the NDPS Act.

Conclusion- In the present case, the seizure was done on 12 December 2021 when the applicant was apprehended at Terminal 3, Indira Gandhi International Airport, New Delhi. On interrogation, she denied carrying any contraband, however, a search of her baggage revealed about 1.873 kg Methaqualone valued at approximately Rupees 93.67 lacs. It is pertinent to note that the threshold for commercial quantity of Methaqualone is 500 grams.

Held that taking into consideration four times the commercial quantity of contraband seized from the instance of the applicant, there being no prejudicial infirmity in the process adopted by the respondent, rigours of Section 37, NDPS Act, and progressing trial, this Court is unable to reach a prima facie conclusion that applicant is not guilty of the offences and is unlikely to commit the same if enlarged on bail. The threshold of Section 37, NDPS Act not having been crossed, the application for bail cannot be granted.

FULL TEXT OF THE JUDGMENT/ORDER OF DELHI HIGH COURT

1. This application has been filed by applicant under Section 439, Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 [“CrPC”] read with Section 37, Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985 [“NDPS Act”] seeking regular bail in case arising out of criminal complaint dated 09th June 2022, bearing File No. VIII(AP) 1 0/P&I/3290-B/ARRIVAL/202 1, by Air Customs Officer, Terminal-3, Indira Gandhi International Airport, New Delhi. Said complaint was filed before the Special Judge (NDPS), Dwarka Court, New Delhi to take cognizance of offences allegedly committed by the applicant under Sections 2 1/23/29 of the NDPS Act.

Factual Background

2. As per the prosecution’s narrative, on 12th December 2021, information was received that applicant would be arriving from Addis Ababa, Ethiopia to Terminal-3, Indira Gandhi International Airport, New Delhi by Flight ET 688 and would be carrying narcotics, pursuant to which, two panch witnesses were called by the Customs Authorities. At about 12:20 hours, applicant was intercepted by matching her passport number and date of birth after she crossed the Green Channel and was asked, in the presence of the panch witnesses, whether she was carrying any narcotic substances on her person or in her baggage to which, she replied in the negative.

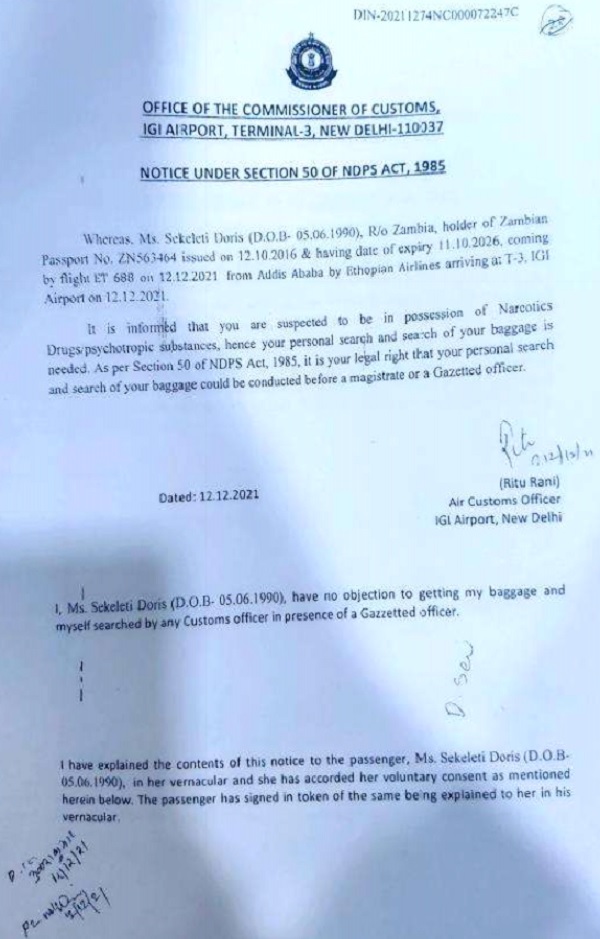

3. Thereafter, notice under Section 50, NDPS Act was issued as well as another notice under Section 102 of the Customs Act, 1962 [“Customs Act”] was served upon the applicant; she was apprised of the fact that her personal search as well as baggage search could be conducted in the presence of a Gazetted Officer or a Magistrate to which, applicant gave her consent to be searched by any lady Customs Officer, and her baggage can be searched by any Customs Officer.

4. The applicant was directed to the Customs Preventive Room and her personal search was done by the lady Customs Officer as well as search of her handbag was done which revealed three unsealed plastic bottles containing off-white thick liquid substances. A small quantity of the off-white-coloured thick liquid was taken from each bottle and tested with the help of Field Drug Test Kit. The samples from all three bottles tested positive for “Methaqualone”. The plastic bottles were each weighed with the help of weighing machine available in the Customs Preventive Room and the gross weight was found to be 958.55 grams, 634.69 grams, and 280.65 grams respectively. Combined gross weight of the off-white-coloured thick liquid was calculated and found to be 1,873.89 grams valued at approximately Rupees 93.67 lacs.

5. Recovered contraband was seized under Section 43(a), NDPS Act read with Section 110, Customs Act alleging violation of Sections 8/23, NDPS Act on the belief that the contraband has been illegally brought to India.

6. Subsequently, the applicant was arrested on the same day i.e. 12th December 2021 and was produced before the Court; applicant is in judicial custody ever since.

7. Applicant moved the Court of Special Judge, NDPS Act, Delhi [“Trial Court”] and vide order dated 28th April 2023, Trial Court dismissed the bail application noting that commercial quantity of contraband was seized and hence, embargo of Section 37, NDPS Act is triggered and as of that date, hurdle of Section 37, NDPS Act was not crossed by the applicant. Hence, applicant has moved the present bail application.

Submissions on behalf of Applicant

8. Planting of Drugs: Counsel for applicant contended that the statement of the recovery witness PW-2 Ms. Ritu Rani was recorded before the Trial Court on 09th April 2024 and 06th June 2024 and the pullandas were opened and after opening, it was found that colour of the thick liquid in the bottle was light brown instead of off-white, and thus, same were planted on the applicant in order to falsely implicate her.

9. Delay in filing Section 52A Application, NDPS Act: Further, it was contended that applicant was apprehended on 12th December 2021 and the application under Section 52A, NDPS Act was moved by the authorities on 24th December 2021 before the court for drawing samples. Thus, there was a delay of 12 days in moving said application; same is in contravention with the law which prescribes moving of the application under Section 52A, NDPS Act within 72 hours of recovery of contraband.

10. Proforma Notice under Section 50, NDPS Act: It was contended that a defective notice which was issued to the applicant under Section 50, NDPS Act as the same did not indicating any ‘receiving’ rendered by applicant prior to her search. Said notice served on the applicant is extracted as under:

11. Defective Notice under Section 102, Customs Act: It was also contended that the notice issued to the applicant under Section 102, Customs Act was defective, in that it did not indicate the applicant’s ‘receiving’ prior to her search. Said notice served on the applicant is extracted as under:

12. Delay in Trial: It was submitted that the applicant was arrested on 12th December 2021 and till date, only 2 witnesses out of 16 witnesses has been examined, in light of which, it is likely that the trial will take an excruciatingly long time during which, the applicant claiming innocence cannot be made to undergo prolonged incarceration.

13. In support of their arguments, counsel for applicant relied on the following judicial precedents:

a. Kashif v. Narcotics Control Bureau 2023 SCC OnLine Del 288;

b. Vinod Nagar v. Narcotics Control Bureau 2024:DHC:1244;

c. Mangilal v. State of Madhya Pradesh 2023 SCC OnLine SC 862;

d. Pankaj @Jatin v. State NCT of Delhi BAIL APPLN. 683/2024, order dated 10th April 2024;

e. Madhuri Chauhan v. State of NCT of Delhi 2024:DHC:5008; and

f. Chibuzo @Chibuzor Cristatus v. State (Govt. of NCT of Delhi) BAIL APPLN.2252/2023, order dated 09th July 2024;

g. Gurpreet Singh v. State of NCT of Delhi 2024:DHC:796;

h. Abdul Kadar Shaikh v. Union of India (Through Narcotic Control Bureau) 2024:BHC-AS:21218; and

i. Gopal Dangi v. State NCT of Delhi 2024:DHC:5175.

Submissions on behalf of Customs

14. Senior Standing Counsel appearing on behalf of Customs refuted the above contentions and submitted that due procedure was followed by the Customs Authorities and full compliance of Section 52A, NDPS Act as well as Section 102, Customs Act was made. Also, compliance of Standing Order [“SO”] Nos 1/88 [issued by the Narcotics Control Bureau] and 1/89 [applicable from 13th June 1989 issued by Government of India, Ministry of Finance] was duly made as well. In any case, these contentions may be raised at the stage of trial and have no bearing on grant/refusal of bail.

15. It was further submitted that since the contraband seized was of commercial quantity, rigours of Section 37, NDPS Act will be triggered. At this stage, the twin conditions imposed by Section 37, NDPS Act cannot be said to have been satisfied as there is abundant evidence to have hold a prima facie view which does not exonerate the applicant from guilt of committing the alleged offences.

16. In support of his arguments, SPP for Customs placed reliance upon the following decisions:

a. Quentin Decon v. Custom 2023:DHC:3897;

b. Umar Sebandeke v. Customs 2024:DHC:5 184;

c. Somdutt Singh @ Shivam v. NCB 2023:DHC:8550;

d. Surender Kumar v. Central Bureau of Narcotics (CBN) 2023:DHC:6309;

e. Mohit Yadav v. State of NCT, Delhi 2024:DHC:3 144;

f. State of Kerala v. Rajesh (2020) 12 SCC 122;

g. State of Gujrat v. Salimbhai Abdulgaffar Shaikh & Ors (2003) 8 SCC 50;

h. State v. Syed Amir Hasnain (2002) 10 SCC 88;

i. Narcotics Control Bureau, Chennai v. R. Paulsamy 2001 SCC (Crl.) 648 (SC);

j. Sanjeev Kumar v. NCB Crl Misc (M) No.3962/2002 decided on 17th February 2003;

k. State of M.P. v. Kajad (2001) 7 SCC 673;

l. Union of India v. Rattan Mallik, (2009) 2 SCC 624; and

m. Khet Singh v. Union of India (2002) 4 SCC 380.

Analysis

17. Heard counsel on behalf of parties and perused the material placed on At the outset, reference may be made to the substance that was seized from the instance of the applicant i.e. Methaqualone which is a psychotropic substance, as envisaged in the NDPS Act. Psychotropic substances are defined in Section 2(xxiii) of the NDPS Act and included in the Schedule to the NDPS Act:

“(xxiii) “Psychotropic substance”means any substance, natural or synthetic, or any natural

material or any salt or preparation of such substance or material included in the list of

psychotropic substances specified in the Schedule;”

18. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Manual on “Recommended Methods for the Identification and Analysis of Methaqualone/Mecloqualone”1 explains the substance Methaqualone as a quinazolone derivative first synthesized in 1951, and used medically as a hypnotic for the short-term treatment of insomnia. It is also rampantly used as a recreational drug as it acts as a central nervous system depressant in a manner not unlike barbiturates. It was commonly marketed as Quaaludes and Mandrax (containing Methaqualone base 250 mg, and dip henhydramine hydrochloride 25 mg) in the 1960s and 1970s; also, as Malsed, Malsedin, and Renoval in the United Kingdom. Due to abuse, addiction and a higher potential to create dependence than the barbiturates, Methaqualone is no longer prescribed in medicine and is widely under international control (Substances in Schedule II of the Convention on Psychotropic Substances 19712). The detrimental effects of hypnotic dependence on Methaqualone arise particularly from the persistence of effects such as ataxia, dysarthia, mental impairment, confusion and poor judgement. Side effects of treatment with Methaqualone or its hydrochloride in therapeutic doses include headaches, hangovers, dizziness, drowsiness, anorexia, nausea and gastrointestinal discomfort, dry mouth, restlessness and sweating. Skin reactions have also been reported. Methaqualone is now only largely illicitly produced in clandestine laboratories. Its main use is as a recreational drug taken orally as a tablet formulation and often smoked when mixed with cannabis (marijuana).

19. In the present case, the seizure was done on 12 December 2021 when the applicant was apprehended at Terminal 3, Indira Gandhi International Airport, New Delhi. On interrogation, she denied carrying any contraband, however, a search of her baggage revealed about 1.873 kg Methaqualone valued at approximately Rupees 93.67 lacs. It is pertinent to note that the threshold for commercial quantity of Methaqualone is 500 grams.

Alleged Planting of Drugs

20. Counsel for applicant has put forth a defence of planting of drugs while referring to the testimony of PW-2 and contended that the seized contraband was of a different colour than which was referred to by the said witness. However, this is an issue which will be decided post-trial, after all evidence has been led, and whether there is a colour change, is it a natural occurrence, specific to he chemical involved or whether the colour change denotes a defect/tampering in seizure or storage of the contraband. At this stage of bail, this issue cannot give any benefit of reasonable doubt to the applicant-

Delay in Filing Section 52A Application

21. The recovery of contraband at the instance of applicant was on 12th December 2021 and seizure was done on the same day in this case. However, applicant states that the application under Section 52A, NDPS Act was moved on 24th December 2021 i.e. after a delay of 12 days, way after 72 hours.

22. In respect of this objection, it is noted that SO 1/89 does not prescribe specific time-period for moving said application. SO 1/88 requires samples to be dispatched to the FSL not later than 72 hours.

23. The Apex Court in Tofan Singh v. State of Tamil Nadu (2021) 4 SCC 1 traversed the international background and need and necessity to enact the NDPS quite succinctly. For the sake of brevity, a short portion is being extracting to capture the essence of the discussion therein as follows:

“24. The NDPS Act has been enacted, inter alia, to implement International Conventions relating to narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances to which India has been a party and also to implement the Constitutional policy enshrined in Article 47 of the Constitution of India, which casts a duty upon the State to improve public health and also to prohibit consumption, except for medicinal purposes, of drugs which are injurious to health.”

(emphasis added)

24. The NDPS Act attempts to strike a balance between personal liberty, conduct of fair trial, and discharging the duty to curb the menace of drugs running rampant in this country. Deliberating upon the inclusion of Section 37 in the NDPS Act, the Apex Court in Union of India v. Ram Sam ujh (1999) 9 SCC 429 elaborated upon the legislative intent of the NDPS Act in the following manner:

“6. The aforesaid section is incorporated to achieve the object as mentioned in the Statement of Objects and Reasons for introducing Bill No. 125 of 1988 thus:

“Even though the major offences are non-bailable by virtue of the level of punishments, on technical grounds, drug offenders were being released on bail. In the light of certain difficulties faced in the enforcement of the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985, the need to amend the law to further strengthen it, has been felt.”

(emphasis supplied)

7. It is to be borne in mind that the aforesaid legislative mandate is required to be adhered to and followed. It should be borne in mind that in a murder case, the accused commits murder of one or two persons, while those persons who are dealing in narcotic drugs are instrumental in causing death or in inflicting death-blow to a number of innocent young victims, who are vulnerable; it causes deleterious effects and a deadly impact on the society; they are a hazard to the society; even if they are released temporarily, in all probability, they would continue their nefarious activities of trafficking and/or dealing in intoxicants clandestinely. Reason may be large stake and illegal profit involved.

…

8. To check the menace of dangerous drugs flooding the market, Parliament has provided that the person accused of offences under the NDPS Act should not be released on bail during trial unless the mandatory conditions provided in Section 37, namely,

(i) there are reasonable grounds for believing that the accused is not guilty of such offence; and

(ii) that he is not likely to commit any offence while on bail

are satisfied. The High Court has not given any justifiable reason for not abiding by the aforesaid mandate while ordering the release of the respondent-accused on bail. Instead of attempting to take a holistic view of the harmful socioeconomic consequences and health hazards which would accompany trafficking illegally in dangerous drugs, the court should implement the law in the spirit with which Parliament, after due deliberation, has amended.”

(emphasis added)

25. The Supreme Court in Ram Samujh (supra), while referring to punishment under the NDPS Act and adverse effects of these activities, also referred to the decision of the Apex Court in Durand Didier v. Chief Secy., Union Territory of Goa (1990) 1 SCC 95; relevant portions of Duran Didier (supra) are reproduced as under:

“24. With deep concern, we may point out that the organised activities of the underworld and the clandestine smuggling of narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances into this country and illegal trafficking in such drugs and substances have led to drug addiction among a sizeable section of the public, particularly the adolescents and students of both sexes and the menace has assumed serious and alarming proportions in the recent years. Therefore, in order to effectively control and eradicate this proliferating and booming devastating menace, causing deleterious effects and deadly impact on the society as a whole, the Parliament in its wisdom, has made effective provisions by introducing this Act 81 of 1985 specifying mandatory minimum imprisonment and fine. As we have now rejected the plea of the defence holding that the penal provisions of Section 2 7(a) has no role to play as the prohibited drugs and substances possessed by the appellant were far in excess of the quantity mentioned in column 3 of the table under the notification, the sentence of 10 years rigorous imprisonment and the fine of Rs 1,00,000 with the default clause as modified by the High Court does not call for interference.”

(emphasis added)

26. To grant bail under the regime of NDPS Act in situations of seizure of commercial quantity of contraband, rigours of Section 37, NDPS Act apply; bare text of the provision reads as under:

“37. Offences to be cognizable and non-bailable.

(1) Notwithstanding anything contained in the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (2 of 1974) (a) every offence punishable under this Act shall be cognizable; (b) no person accused of an offence punishable for offences under Section 19 or Section 24 or Section 27-A and also for offences involving commercial quantity shall be released on bail or on his own bond unless-

(i) the Public Prosecutor has been given an opportunity to oppose the application for such release, and

(ii) where the Public Prosecutor oppose the application, the court is satisfied that there are reasonable grounds for believing that he is not guilty of such offence and that he is not likely to commit any offence while on bail.

(2) The limitations on granting of bail specified in clause (b) of sub-section (1) are in addition to the limitations under the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (2 of 1974), or any other law for the time being in force, on granting of bail.”

(emphasis added)

27. Counsel for applicant relies upon Kashif (supra), a decision of a coordinate Bench of this Court, in order to contend that delay in filing Section 52A application ought to render the Court to afford benefit of doubt to the applicant. Relevant portions of Kashif (supra) are as under:

“24. Hence, I am of the view that non-compliance of section 52A within a reasonable time gives rise to the apprehension that sample could have been tampered with and in case of a wrongly drawn sample, the benefit of doubt has to accrue to the accused. The prosecuting agency has to prove at the time of trial that the sample was immune from tampering.

25. In the present case, the sample was kept in the custody of the prosecuting agency for more than one and a half month, thus, raising doubt with regards to tampering of the same.

26. Another reason which persuades me to take this view is that once the Apex Court has held in Mohanlal (supra) that the application under 52A has to be made without any undue delay, there should not be any reason for delaying the filing of application.

27. The application for sample collection under section 52A is not a technical application wherein elaborate reasons, principles of law or detailed facts are required. It is more of a clerical application and should mandatorily be made within a reasonable time under section 52A NDPS. The application has to be moved at the earliest and in case, the same has not been moved, the reasons for delay must be explained by the authorities.

Reasonable time under section 52A

28. What is reasonable time depends on the facts and circumstances of each case. However, it cannot be the intention of the legislature that an application for sample collection can be moved at the whims and fancies of the prosecuting agency. Therefore, taking cue from the Standing Order 1/88, it is desirable that the application under 52A should be made within 72 hours or near about the said time frame.”

(emphasis added)

28. Thereafter, another coordinate Bench of this Court in Somdutt Singh @ Shivam (supra) distinguished the judgment in the case of Kashif (supra) on the aspect that no recovery was effected from the possession or at the instance of the applicants therein and thus, embargo of Section 37 was not attracted. While dismissing the bail application, Court in Somdutt Singh @ Shivam (supra) observed as follows:

“16. Furthermore, recently a Co-ordinate Bench of this Court in Surender Kumar (supra) has observed that Section 52-A of the NDPS Act is directory in nature and non-compliance of the same, in itself, cannot render the investigation invalid. Accordingly, the bail application of an accused charged of illegally selling narcotic medicines was dismissed by taking into account that the case involved commercial quantity of such medicines.

17. It is clear from a reading of the aforesaid judgments that there is no mandatory time duration prescribed for compliance of Section 52- A of the NDPS Act. Though it is desirable that the procedure contemplated in Section 52-A of the NDPS Act be complied with at the earliest, mere delayed compliance of the same cannot be a ground for grant of bail. The applicant will have to show the prejudice caused on account of delayed compliance of Section 52-A of the NDPS Act.”

(emphasis added)

29. The decision in Somdutt Singh (supra) was challenged before the Apex Court in Special Leave Petition (Crl.) No. 415/2024. By order dated 16th May 2024, Court dismissed the said special leave petition.

30. In the present case, the application under Section 52A, NDPS Act was preferred 12 days after the seizure of the contraband from the applicant. The applicant may, in accordance with applicable law, contend prejudice caused on account of this delay, during trial. The judgement of a coordinate Bench in Sovraj v. State 2023:DHC:8550, on similar lines, had observed as under:

“57. It is pertinent to note that he Hon’ble Apex Court in the case of Union of India v. Mohanlal (supra) had specifically noted that while the process of sampling cannot be left to the whims of the prosecution and the application for sampling and certification ought to be made without undue delay, there was no room for prescribing or reading a time-frame into the provision. Though no timeframe has been incorporated in the provision, the application should be made without undue delay. The cause of delay, however, in the opinion of this Court, can be explained by the prosecution during the course of trial and is not fatal.

58. As long as the prosecution is able to justify the delay on its end, mere delay would not vitiate the evidence. To hold otherwise would lead to an odd situation where even a few hours post the threshold of 72 hours would nullify the evidence. The Court has to be cognizant of the ground realities where situations may arise where the sample was not sent to FSL on time or the application under Section 52A of the NDPS Act could not be preferred on time.”

(emphasis added)

31. Although in Sovraj (supra), this Court had enlarged the accused on bail, same was done inter alia on the issue of absence of independent witnesses and lack of photography or videography of the recovery. Same do not form basis of applicant’s contentions herein and thus, application of law in this case will have to be done in the facts and circumstances of this case. In the present matter, at this stage, this Court is of the opinion that the applicant has failed to overcome the threshold as prescribed by Section 37, NDPS Act. Defective Notice

32. As far as the issue of proforma notice is concerned, it may be noted that provision of Section 50, NDPS Act needs to be complied with only in cases of personal search and not of the person searched. In this regard reference is made to the decision of the Supreme Court in Ranjan Kumar Chadha v. State of Himachal Pradesh 2023 SCC OnLine SC 1262. Objections as regards defective notice under Section 50, NDPS Act or Section 102, Customs Act may not be finally relevant since nothing was revealed in a personal search of the accused. Provisions of Section 50, NDPS Act need to be complied with only in cases of personal search and not where it is of the bag of the person being searched. Relevant portions of Ranjan Kumar Chadha (supra) are extracted as under:

“93. Thus, in Pawn Kumar (supra) the larger Bench while answering the reference in no uncFrtain teLQ\ \tatted t VI Va D g, briefcase\e or any such article or container, etc. can, under no circumstances, be treated as body of a human being. They are given a separate name and are identifiable as such. They cannot even remotely be treated to be L Hot of the L1Sdy of a 1RL n b[ILIER

94. The Court reasoned that a person of varying capacity can carry different items on his or her body but that does not make those items as a part of body Th7 1-ILI t Rb\reverie , EVepUYdiGg upon the physical capacity of a person, he may carry any number of items like a bag, a briefcase, a suitcase, a tin box, a thaila, a jhola, a gathri, a holdall, a carton, etc. of varying size, dimension or weight. However, while carrying or moving along with them, some extra effort or energy would be required. They would have to be carried either by the hand or hung on the shoulder or back or placed on the head. In common parlance it would be said that a person is carrying a particular article, specifying the manner in which it was carried like hand, shoulder, back or head,

95. Therefore, Pawan Kumar (supra) concluded that an external article which does not form part of body is outside the ambit of the word “person” occurring in Section 50 of the NDPS Act.

96. What is most important to note in Pawan Kumar (supra) is that the search was not only of the bag, but also of the person of the accused, however, the contraband was recovered only from the bag and not from the person of the accused therein. What we are trying to highlight is that although in Pawan Kumar (supra) the search was of the accused as well as the bag, yet since the recovery of the contraband was only from the bag, this Court took the view that Section 50 would have no application.

…

103. Accordingly, Section 50 was read to be understood as applicable only to the personal search of a person and that would not extend to search of a vehicle or a container or a bag.”

(emphasis added)

33. As noted by the Supreme Court in State of Himachal Pradesh v Pawan Kumar 2005 4 SCC 350, the search was both of applicant as well as of the luggage she was carrying, but since nothing was recovered from her personal search, Section 50 would not apply.

34. However, a note of caution is to be made regarding these proforma notices as reproduced in paragraphs 10 and 11 above. Though the signatures of the accused are there of having “received” the notice, with the signatures of the witnesses as well, there is a pre-typed no objection for search to be conducted by a lady customs officer under which the sign is procured of the accused. This practice may not be totally correct considering that Section 50 requires options to be given to the person being searched; in fact an affirmative option is to be exercised for the search being conducted before the nearest Gazette Officer/Magistrate. Having provided a pre-typed preformat, with the less desirable option and getting it endorsed by the signatures of the person being searched, that too in the heat of the moment of the raid/seizure, is a practice which is to be deprecated. A preformat typed notice may ideally have both the options i.e. first that the person requires the personal search to be done before a Gazette Officer/Magistrate; and second that the person to be searched has no objection to being searched by an officer present (lady officer in case the person to be searched is female).

35. Customs is well-advised to alter their preformat notices to introduce the above options in consonance with requirements of Section 50 as sanctified by decisions of Supreme Court inter alia in Raman Kumar Chadha (supra). In this regard, following paragraphs of the said judgment have been reproduced below for reference:

“64. There is no requirement to conduct the search of the person, suspected to be in possession of a narcotic drug or a psychotropic substance, only in the presence of a Gazette Officer or Magistrate, if the person proposed to be searched, after being apprised by the empowered officer of his right under Section 50 of the NDPS Act to be searched before a Gazette Officer or Magistrate categorically waives such right by electing to be searched by the empowered officer. The words “if such person so requires” as used in Section 50(1) of the NDPS Act would be rendered otiose, if the person proposed to be searched would still be required to be searched only before a Gazetted Officer or Magistrate, despite have g expreswaived “ ch requisition” as me tioned in the opening sentence of sub-Section (2) of Section 50 of the NDPS Act. In other words, the person to be searched is mandatorily required to be taken by the empowered officer, for the conduct of the proposed search before a Gazette Officer or Magistrate, only “if he so requires” upon being informed of the existence of his right to be searched before a Gazette Officer or Magistrate and not if he waives his right to be so searched voluntarily, and chooses not to exercise the right provided to him under Section 50 of the NDPS Act.

65. However, we propose to put an end to all speculations and debate on this issue of the suspect being apprised by the empowered officer of his right under Section 50 of the NDPS Act to be searched before a Gazetted Officer or Magistrate. We are of the view that even in cases wherein the suspect waives such right by electing to be searched by the empowered officer, such waiver on the part of the suspect should be reduced into writing by the empowered officer. To put it in other words, even if the suspect says that he would not like to be searched before a Gazette Officer or Magistrate and he would be fine if his search is undertaken by the empowered officer, the matter should not rest with just an oral statement of the suspect. The suspect should be asked to give it in writing duly signed by him in presence of the empowered officer as well as the other officials of the squad that “I was apprised of my right to be searched before a Gazette Officer or Magistrate in accordance with Section 50 of the NDPS Act, however, I declare on my own free will and volition that I would not like to exercise my right of being searched before a Gazette Officer or Magistrate and I may be sear Rued [I the \ wk.-IL Wirier.” This Wild lend more credence to the compliance of Section 50 of the NDPS Act. In other words, it would impart authenticity, transparency and credit worthiness to the entire proceedings. We clarify that this compliance shall henceforth apply prospectively.

66. (iv) While informing the right, only two options of either being searched in presence of a Gazette Officer or Magistrate must be given, who also must be independent and in no way connected to the raiding party.”

(emphasis added)

Delay in Trial/Prolonged Incarceration

36. The plea of delay in trial and prolonged incarceration, though being recognized by the Supreme Court as an inalienable right under Article 21 of the Constitution of India cannot have a formulaic application. There have been various decisions of the Supreme Court on the aspect of delay in trial, the relevant paragraphs of the same have been extracted as under:

i. Rabi Prakash v State of Odisha 2023 SCC OnLine SC 1109 where a recovery of 247 kgs of ganja was made and the petitioner had been in custody for more than three and a half years, with no criminal antecedents, the Court held as under:

“4. As regard to the twin conditions contained in Section 37 of the NDPS Act, learned counsel for the respondent – State has been duly heard. Thus, the 1st condition stands complied with. So far as the 2nd condition re: formation of opinion as to whether there are reasonable grounds to believe that the petitioner is not guilty, the same may not be formed at this stage when he has already spent more than three and a half years in custody. The prolonged incarceration, generally militates against the most precious fundamental right guaranteed under Article 21 of the Constitution and in such a situation, the conditional liberty must override the statutory embargo created under Section 37(1) (b) (ii) of the NDPS Act.”

ii. Dheeraj Kumar Shukla v State of U.P. 2023 SCC OnLine SC 918 where there was a seizure of about 65 kgs of ganja and the petitioner was in custody for about two and a half years, the Supreme Court while granting bail, stated as under:

“3. It appears that some of the occupants of the +oL1QaGDitLI’GLW1GiL1 luDiL1LGL1aFeeL1GLQu1LIa GUD G Puneet Maurya have since been released on regular bail. It is true that the quantity recovered from the petitioner is commercial in nature and the provisions of Section 37 of the Act may ordinarily be attracted. However, in the absence of criminal antecedents and the fact that the petitioner is in custody for the last two and a half years, we are satisfied that the conditions of Section 37 of the Act can be dispensed with at this stage, more so when the trial is yet to commence though the charges have been framed.”

iii. In Man Mandal & Anr. v State of West Bengal 2023 SCC OnLine SC 1868 where the seizure was commercial in nature and the petitioner had been incarcerated for about two years and there was no hope of the trial concluding soon, the Supreme Court while granting bail stated as under:

“6. Taking into consideration the fact that the petitioners have been incarcerated for a period of almost two years and the trial is not likely to be taken up for hearing in the immediate near future, we are inclined to grant bail to the petitioners.”

iv. In Badsha Sk. v State of West Bengal 2023 SCC OnLine SC 1867 where the seizure was of 100 bottles of Phensedyl Cough Syrup (100 ml. each), containing Codeine Phosphate, the petitioner had been in custody for about 2 years 4 months and the trial was yet to commence, the Supreme Court while granting bail noted as under:

“5. The above would show that the trial is yet to commence in the matter(s) and in the meantime, petitioners have been in custody for long. The State counsel submits that there are no known criminal antecedents against the two accused.”

37. Assessment of these decisions of the Supreme Court cited above shows that bail has been granted in cases having differing facts, some with incarceration of more than 3 years, and some in cases of seizure of ganja. The assessment, therefore, on prolonged custody and delay in trial will depend of facts and circumstances of the case. Whether 2 or 3 years or more, or any other time period is “prolonged”, is clearly left to the assessment of the Court.

38. In this case, the petitioner has undergone almost 3 years of custody and the trial is progressing. An attempt may be made by the Trial Court to expedite the trial. In the event, that the trial does not proceed ahead expeditiously, needless to state that the applicant will have the right to approach the Court at a subsequent stage.

39. In this regard, it is to be noted that in the decision of the Supreme Court in Supreme Court Legal Aid Committee (Representing Undertrial Prisoners) v. Union of India (1994) 6 SCC 731 in context of incarceration as an undertrial and delay in disposal of cases it was stated inter alia that when an undertrial is charged with offences with minimum imprisonment of 10 years, and if he has been in jail for not less than 5 years, he may be released on bail upon furnishing bail bond in the sum of Rupees one lakh with two sureties for like amount. This view has been endorsed in Thana Singh v. Central Bureau of Narcotics (2013) 2 SCC 603 as under:

“4. Time and again, this Court has emphasised the need for speedy trial, particularly when the release of an undertrial on bail is restricted under the provisions of the statute, like in the present case under Section 37 of the NDPS Act. While considering the question of grant of bail to an accused facing trial under the NDPS Act in Supreme Court Legal Aid Committee (Representing Undertrial Prisoners) v. Union of India [(1994) 6 SCC 731 : 1995 SCC (Cri) 39] this Court had observed that though some amount of deprivation of personal liberty cannot be avoided in such cases, but if the period of deprivation pending trial becomes unduly long, the fairness assured by Article 21 of the Constitution would receive a jolt. It was further observed that after the accused person has suffered imprisonment, which is half of the maximum punishment provided for the offence, any further deprivation of personal liberty would be violative of the fundamental right visualised by Article 21. We regret to note that despite it all, there has not been visible improvement on this front.”

(emphasis added)

40. In light of the above discussion, taking into consideration four times the commercial quantity of contraband seized from the instance of the applicant, there being no prejudicial infirmity in the process adopted by the respondent, rigours of Section 37, NDPS Act, and progressing trial, this Court is unable to reach a prima facie conclusion that applicant is not guilty of the offences and is unlikely to commit the same if enlarged on bail. The threshold of Section 37, NDPS Act not having been crossed, the application for bail cannot be granted.

41. Bail application stands dismissed.

42. Needless to state that any observations made herein are only for the purpose of deciding the present bail application and should not be read as a comment upon the merits of the case.

43. Judgment be uploaded on the website of this Court.

Notes:

1 United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2010) Recommended methods for the identification and analysis of methaqualone/mecloqualone. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. https://syntheticdrugs.unodc.org/uploads/syntheticdrugs/res/library/forensics html/Recommended Methods for the identification and analysis of Methaqualone Mecloqualone ST-NAR-15 and Rev.1.pdf (accessed October 16 2024).

2 UN General Assembly, 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances, A/RES/3443, UN General Assembly, 9 December 1975, https://www.refworld.org/legal/resolution/unga/1975/en/9579 [accessed 16 October 2024].