Case Law Details

Ananthamurthy & Anr. Vs J. Manjula ETC (Supreme Court of India)

Key Legal Issues- The Supreme Court examined the following legal questions:

1. Does a General Power of Attorney (GPA) confer ownership rights upon the holder

2. What is the legal effect of an unregistered Agreement to Sell

3. Can a GPA holder execute a sale deed after the death of the principal

4. Whether a suit for permanent injunction is maintainable without a declaratory relief regarding title

Supreme Court’s Observations and Ruling:

The Supreme Court reaffirmed the legal principles established in Suraj Lamp & Industries Pvt. Ltd. v. State of Haryana [(2012) stating:

“A General Power of Attorney is fundamentally an instrument of agency and ceases to exist upon the death of the principal. Transactions based on such an instrument after the principal’s death are legally void.”

Immovable property can be legally and lawfully transferred/conveyed only by a registered deed of conveyance. Transactions of the nature of “GPA sales” or “SA/GPA/will transfers” do not convey title and do not amount to transfer, nor can they be recognised or valid mode of transfer of immovable property. The courts will not treat such transactions as completed or concluded transfers or as conveyances as they neither convey title nor create any interest in an immovable property. They cannot be recognised as deeds of title, except to the limited extent of Section 53-A of the TP Act. Such transactions cannot be relied upon or made the basis for mutations in municipal or revenue records. What is stated above will apply not only to deeds of conveyance in regard to freehold property but also to transfer of leasehold property. A lease can be validly transferred only under a registered assignment of lease. It is time that an end is put to the pernicious practice of SA/GPA/will transactions known as GPA sales.”

Regarding the unregistered Agreement to Sell, the court emphasized: “An unregistered sale agreement does not convey ownership. Under the Transfer of Property Act, 1882, and the Registration Act, 1908, a registered conveyance deed is mandatory for the legal transfer of ownership rights.”

“An agent or power of attorney holder derives authority strictly from the instrument of agency. Once the principal dies, the agent’s authority ends unless it is explicitly coupled with an interest that survives beyond the principal’s lifetime.”

“A claim to ownership of immovable property must be pursued within the statutorily prescribed period. The appellants failed to act within the legal timeframe, rendering their claim unsustainable.”

Registration provides safety and security to transactions relating to immovable property, even if the document is lost or destroyed. It gives publicity and public exposure to documents thereby preventing forgeries and frauds in regard to transactions and execution of documents. Registration provides information to people who may deal with a property, as to the nature and extent of the rights which persons may have, affecting that property. In other words, it enables people to find out whether any particular property with which they are concerned, has been subjected to any legal obligation or liability and who is or are the person(s) presently having right, title, and interest in the property. It gives solemnity of form and perpetuate documents which are of legal importance or relevance by recording them, where people may see the record and enquire and ascertain what the particulars are and as far as land is concerned what obligations exist with regard to them. It ensures that every person dealing with immovable property can rely with confidence upon the statements contained in the registers (maintained under the said Act) as a full and complete account of all transactions by which the title to the property may be affected and secure extracts/copies duly certified.”

Registration of documents makes the process of verification and certification of title easier and simpler. It reduces disputes and litigations to a large extent.”

FULL TEXT OF THE SUPREME COURT JUDGMENT/ORDER

1. Leave granted.

2. Since the issues raised in both the captioned appeals are the same, the parties are also same and the challenge is also the self-same, hence those were taken up analogously and are being disposed of by this common judgment and order.

3. These appeals have been filed before this Court from the judgment and order passed by the High Court of Karnataka at Bengaluru dated 16.10.2019 in R.F.A. No. 1318/2014 c/w R.F.A. No. 1317/2014 (“impugned judgment”) whereby the High Court dismissed the appeals and affirmed the common judgment and decree dated 21.06.2014 passed in O.S. No. 133/2007 and O.S. No. 4045/2008 by the Court of VIII Additional City Civil & Sessions Judge at Bengaluru City.

A. FACTUAL MATRIX

4. The description of the parties before this Court, the High Court and before the Trial Court is tabulated as follows:-

| BEFORE THIS COURT |

BEFORE THE HIGH COURT |

BEFORE THE TRIAL COURT | REMARKS |

| Muniyappa | – | – | Original Owner |

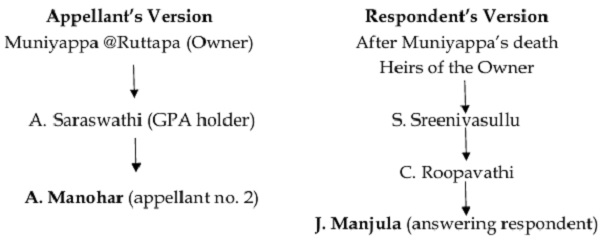

| A. Saraswathi | – | – | Holder of POA |

| Appellants | Petitioners | Plaintiff in O.S. No. 4045/2008 |

Defendant in suit instituted by the respondent no. 9 |

| Respondent Nos. 1-6 | Respondent Nos. 1-6 | Defendant Nos. 1-6 |

Legal heirs of original owner |

| Respondent No. 7 | Respondent No. 7 | Defendant No. 7 | Purchaser |

| Respondent No. 8 | Respondent Nos. 8-10 | Defendant No.

8 |

Purchaser |

| Respondent No. 9/Answering Respondent |

Respondent No. 11 | Plaintiff in O.S. No. 133/2007 |

Defendant no. 9 in suit instituted by the appellants/Gift Deed Holder |

Appellant no. 2 was represented by his general power of attorney holder i.e., appellant no. 1, for the purposes of the appeal before the High Court and this Court.

5. The dispute arises from a common claim put forward by the appellants and the answering respondent on property bearing Site No. 10, out of Sy. No. 55/1, situated at Chunchaghatta Village, Uttarahalli Hobli, Bangalore South Taluk (hereinafter referred to as “Suit Property”). The Suit Property originally formed part of 1 acre 8 guntas of land situated in Chunchaghatta Village, Uttarahalli Hobli, Bangalore South Taluka within the revenue limits of Konanakunte Gram Panchayat owned by late Muniyappa @ Ruttappa (hereinafter referred to as “original owner”). The original owner developed the said land in the form of individual plots and sold those plots for consideration to various person. The Suit Property is one of those plots.

6. It is the case of the appellants that on 04.04.1986, the Suit Property was sold by the original owner one A. Saraswathi (hereinafter referred to as “holder”) for total sale consideration of Rs.10, 250/- by executing an irrevocable power of attorney (hereinafter referred to as “POA”) and an unregistered agreement to sell. The contents of the said POA and agreement to sell are extracted hereinbelow:-

“GENERAL POWER OF ATTORNEY

KNOW ALL MEN BY THESE PRESENTS THAT, I, Muniyappa urf Ruttappa Son of Ragallappa, Major, residing at Vajarahalli village, Uttarahalli Hobli, Bangalore South Taluk do hereby appoint, nominate and constitute Smt. A. Saraswathi W/O M. S. Anantha Murthy, residing at No. 155, 5th Cross, Wilsongarden, Bangalore – 560 027 as my General Power of Attorney holder to do the following acts, deeds and things on my behalf that is to say:

1) To look after, maintain, manage the Schedule Property in the best manner as my attorney deems fit.

2) To enter into any type of agreements in respect of the Schedule property with any person for any amount, receive advance amount, issue proper receipts, apply to the competent authority seeking permission to execute any type of deeds, in favour of any persons, and to execute such deeds in favour of such persons, receive full consideration amount, issue proper discharge thereof, sign all deeds, forms etc., etc.,

3) To apply for transfer of Khata and to pay all future taxes and to receive proper receipts.

4) To apply for sanctioned plan for construction of any type of building on the property and to construct such building, utilise the same as my attorney deems fit and to get all profits therefrom.

5) To represent me in respect of the Schedule property in all Government offices, BDA, BWSSB, KEB, Corporation etc., etc., apply for any type of documents, receive the same, and approach BDA for reconvey of Schedule property, to pay all betterment charges and to do all connected things.

6) In case of complications to sue such matters in proper courts, of law by engaging the service of advocates or advocate, sign all forms, vakalath, suits, petitions, etc, produce any documents in court, take any documents from the court, give evidence, obtain decree, execute the sale or enter into compromise.

7) The Schedule property is in my peaceful possession and enjoyment thereof as absolute owner thereof.

8) My Attorney is ge11erally entitled to do all such acts, deeds and things, in respect of the Schedule property, which are not specifically written hereunder and I do hereby agree to ratify confirm all such acts, deeds and things done by my attorney as the acts, deeds and things done by me in person and this G.P.A. is irrevocable in nature.

SCHEDULE

Site No. 10, out of Sy. No. 55/1, situated at Chunchaghatta Village, Uttarahalli Hobli, Bangalore South Taluk, measuring East to West 30 feet and North to South (40-6” + 42-3”)/2 feet and bounded as follows:-

East by: Property No. 11

West by: Property No. 9

North by: Road &

South by: Private Property

In witnesses whereof I the executant above named signed this General Power of Attorney on this 4th day of April 1986 at Bangalore.

Identified by me

Executant

Execution admitted before me

S.B. Chandrasekhar

Bangalore Metropolitan Area

Notary

Bangalore

Date: 4-4-1986

SALE AGREEMENT

This Deed of Sale Agreement is made on this 4th day of April, 1986 at Bangalore and executed by Sri. Muniyappa urf Ruttappa, Son of Ragallappa, residing at Chunchaghatta village, Uttarahalli Hobli, Bangalore South Taluk hereinafter called the “VENDOR” (which term shall mean and include all his heirs, executors, administrators and assignees) of the one part and in favour of Srimathi. A. Saraswathi W/O, Ananthamurthy, residing at No. 155, 5th Cross, Wilson Garden, Bangalore-560 027 hereinafter called the “PURCHASER” (which term shall mean and include all heirs, executors, administrators and assignees) of the other part witnesseth as follows:~

WHEREAS the Vendor is the absolute owner in peaceful possession and enjoyment of the Schedule Property more fully described in the Schedule hereunder.

And whereas the Vendor is in need of funds for the maintenance of his family and other legal necessities he desired to sell the Schedule Property in favour of the purchaser for a sum of Rs 10,250/-(Rs. Ten thousand two hundred fifty only) to which the Purchaser duly agreed to purchase the same for the said sum of Rs. 10,250/- only. In pursuance of this Sale agreement the purchaser paid a sum of Rs. 5,000/- on 20-5-1985 through a Cheque No. 0861556 of Syndicate Bank, Wilsongarden Branch, Bangalore and a sum of Rs. 5,250/- only Cheque No. 039 529/243 dated 3.4.86 of Syndicate Bank Wilson Garden, Bangalore total the Vendor received the full sale consideration of Rs.10,250/- only. This day the Vendor handed over the vacant possession of the Schedule property to the purchaser to have and to hold the same as absolute owner. As there is a prohibition of selling the revenue sites by the Government of Karnataka the Vendor could not execute the sale deed. As and when the Government of Karnataka revokes the fragmentation act the Vendor execute the sale deed.

This day the Vendor handed over the vacant possession of the Schedule property to the purchaser, the Vendor have no objection to construct a dwelling house on the Schedule property the Vendor have no objection to transfer the Khata of the Schedule Property to the name of the purchaser.

The Vendor assures the purchaser that the schedule property is free from all kinds of encumbrances and it is free from all taxes.

SCHEDULE:- Site No. 10, out of Sy. No. 55/1, situated at Chunchaghatta Village, Uttarahalli Hobli, Bangalore South Taluk, measuring East to West 30 feet and North to South (40-6” + 42-3”)/2 feet and bounded as follows:-

East by: Property No. 11

West by: Property No. 9

North by: Road &

South by: Private Property

In witnesses whereof both the parties have affixed their signatures to this sale agreement on the day, month and the year above first written.

WITNESSES:

1.

2.

3.

VENDOR

PURCHASER”

7. On the same day, the said POA was duly notarized. On 30.01.1997, the original owner, executant of the POA died. On 01.04.1998, the holder of POA executed a registered sale deed with respect to the Suit Property in favour of her son, i.e., the appellant no. 2, in exchange of sale consideration of Rs. 84,000/-.

8. On the other hand, several years after the death of the original owner, his legal heirs through a registered sale deed dated 21.03.2003 sold the same Suit Property to the respondent no. 7 for total sale consideration of Rs. 76,000/-. Subsequently, respondent no. 7 sold the Suit Property to the respondent no. 8 vide another registered sale deed dated 29.09.2003 for total sale consideration of Rs. 90,000/-. Then, on 06.12.2004, the respondent no. 8 executed a registered gift deed in favour of her daughter, i.e., the answering respondent.

9. It is the case of the appellants that after a long period of time, the father of appellant no. 2, i.e., the appellant no. 1 herein, visited the Suit Property on 02.01.2007. To his shock and surprise, he found strangers in possession of the Suit Property. He, accordingly, lodged a police complaint with the concerned police station. The occupants as well as the answering respondent were called by the police to the police station. However, the police closed the matter saying that the dispute was civil in nature.

10. Later, the answering respondent filed O.S. No. 133/2007 for permanent injunction against the appellant no. 2 or anyone else acting under him from interfering with the peaceful possession and enjoyment of the Suit Property.

Following this, the appellant no. 2 also filed O.S. No. 4045/2008 against the legal heirs of the original owner, the subsequent purchasers and the answering respondent respectively for declaration of sale deeds executed on 21.03.2003 and 29.09.2003 respectively, and the gift deed executed on 06.12.2004 as null and void. He sought further declaration of absolute ownership and direction to handover vacant physical possession of the Suit Property. Both the suits were consolidated and tried together by way of recording common evidence.

11. Upon appreciation of the oral as well as documentary evidence on record, the Trial Court vide its common judgment and order dated 21.06.2014 decreed the O.S. No. 133/2007 filed by the answering respondent by granting a decree of permanent injunction in her favour and dismissed the O.S. No. 4045/2008 filed by the appellant no. 2 herein.

12. The findings recorded by the Trial Court in its judgment and order can be better understood in four parts:-

(i) First, on the issue of possession the Trial Court recorded that it was an admitted position that the answering respondent was in possession of the Suit Property. Further, the registered sale deed dated 29.09.2003 reflected that the respondent no. 8 had purchased the Suit Property from the respondent no. 7 for total sale consideration of Rs. 90,000/- and then respondent no. 8 gifted the property to the answering respondent vide the registered gift deed dated 06.12.2004. While, evaluating the evidence adduced by the appellants (defendants therein) the Trial Court from the cross-examination of appellant no. 1 recorded that two days prior to 01.04.1998, he had visited the Office of Sub-Registrar and found that the revenue site was being registered. Further, it was an admitted position that, though allegedly, a general power of attorney (“GPA”) and agreement to sell were executed by the original owner in favour of the holder in the year 1986, yet the appellant no. 2 was not in possession of the Suit Property as on the date of the institution of the suit. The Trial Court held that the answering respondent is the donee of the Suit Property and is in lawful possession and that the appellant no. 2 is not entitled to seek recovery of possession.

(ii) Secondly, on the issue of legality of registered sale deed dated 21.03.2003 that was executed by the respondent nos. 1-6 in favour of the respondent no. 7, the Trial Court proceeded with the premise that it was an admitted position that as on the date of institution of suit, the appellants were not in possession of the Suit Property. It held that though, the original owner had executed the GPA and the agreement to sell, yet the holder of POA failed to get it registered in time. The contention of the appellants that the GPA and the agreement to sell respectively were not registered in 1986 due to a prohibition on the registration of revenue lands was rejected. It was held by the Trial Court that for transfer of ownership in immovable property, whose value is more than Rs. 100/-, the conveyance has to be mandatorily registered as per Section 17 of the Registration Act, 1908 (for short, “Registration Act”) and sale by GPA is not recognized by law. By placing reliance on Suraj Lamp & Industries Pvt. Ltd. v. State of Haryana, reported in (2012) 1 SCC 656, the Trial Court held that the sale deed dated 01.04.1998 executed by the holder of POA in favour of the appellant no. 2 was invalid along with the admitted position that it was executed after the death of the original owner. Thus, it was held that the registered sale deed dated 21.03.2003 executed in favour of the respondent no. 7 was legal.

(iii) Thirdly, on the issue of legality of registered sale deed dated 29.09.2003 which was executed by the respondent no. 7 in favour of the respondent no. 8, and the registered gift deed dated 06.12.2004 which was executed by the respondent no. 8 in favour of the answering respondent, the Trial Court held that the appellants failed to prove that the above-mentioned sale deed and gift deed were illegal, null and void. At the same time, it held that the respondent no. 8 had a valid title over the Suit Property so as to execute the gift deed in favour of the answering respondent.

(iv) Lastly, on the issue of maintainability of the suit instituted by the appellants, the Trial Court held that the suit instituted by the appellants was barred by limitation. It held that as per Article 58 of the Limitation Act, 1963 (for short, “Act of 1963”), for the purpose of challenging the sale deeds dated 21.03.2003 and 29.09.2003 respectively and the gift deed dated 06.12.2004, he should have presented the suit within three years from the date of the alleged sale deed or agreement to sell as he had come to know about the sale transactions in the year 2003 itself.

B. IMPUGNED JUDGMENT

13. Being aggrieved by the order of the Trial Court, the appellants/judgment debtor, preferred First Appeal. The High Court framed the following points for determination:-

“14. In the light of the above, the points that arise U for my consideration in this appeal are:-

1] Whether the appellant herein (plaintiff in O.S.No.4045/2008) proves that he is the absolute owner of the suit schedule property?

2] Whether the registered Sale Deed dated 01-04-1998 in favour of the plaintiff in O.S.No.4045/2008 executed by Smt. A. Saraswathi as a General Power of Attorney holder would convey a valid title in favour of the plaintiff?

3) Whether the plaintiff in O.S.No.133/2007 would prove that she is in lawful possession of the property as on the date of the institution of the suit?

4] Whether the plaintiff ln O.S.No.133/2007 has proved that there was an interference in her lawful possession of the suit schedule property by the defendants?

5) Whether the common judgment and the decrees under appeals deserve interference at the hands of this Court?”

14. The High Court dismissed both the appeals and thereby affirmed the judgment and decree passed by the Trial Court. The High Court dismissed the appeals on four grounds:-

(i) First, the High Court held that the appellants had not denied or disputed the existence of the two registered sale deeds dated 21.03.2003 and 29.09.2003 respectively and the gift deed dated 06.12.2004 in the suit preferred by the answering respondent. The said documents made it amply clear that the Suit Property was sold by the legal representatives of the original owner in favour of the respondent no. 7, who in turn vide a registered sale deed then sold the same Suit Property to the respondent no. 8. The respondent no. 8 thereafter gifted the Suit Property to her daughter, i.e., the answering respondent by way of a registered gift deed dated 06.12.2004. Accordingly, answering respondent is the lawful owner in possession of the Suit Property.

The relevant observations read as under:-

“22. As already observed above, the plaintiff in O.S.No. 4045/2008 has not denied or disputed the documents at Exs. P-1, P-2, P-3 which are two registered Sale Deeds and a Gift deed respectively. By virtue of the said documents, it goes to show that the suit schedule property was sold by the legal representatives of the deceased Muniyappa @ Ruttappa in favour of one Sri. S. Sreenivasulu on 21-032003 which Sreenivasulu in turn sold the very same suit scheduled property to one Smt. C. Roopavathi (the mother of the plaintiff in O.S.No.133/2007) under a registered Sale Deed dated 29-09-2003. The said Smt. C. Roopavathi, in turn, has gifted the said property to her daughter – Smt.J. Manjula (plaintiff in O.S.NO.133/2007) under a registered Gift Deed dated 06-12-2004. It is based upon these documents and the subsequent documents like tax paid receipts, self-declaration of property tax and the water bill and water tax receipt which have all been produced as exhibits in ‘P’ series as observed above, the learned counsel for the plaintiff in O.S.No.133/2007 (Respondent in R.F.A.No.1318/2014) contends that, it is Smt. J. Manjula – the plaintiff in O.S.No.133/2007 has been in lawful possession of the suit schedule property in her capacity as the owner of the suit schedule property.”

(ii) Secondly, the High Court observed that the appellant no. 1 in his cross-examination had admitted that the original owner-executant of POA, died on 30.01.1997. It is further an admitted position that the registered sale deed in favour of the appellant no. 2 was executed on 01.04.1998 i.e., after the death of the executant. The said sale deed was executed by the holder of POA in her capacity as a GPA holder of the original owner. Therefore, the execution of sale deed dated 01.04.1998 was after the death of the executant of GPA. The appellants submitted that since the holder had an interest in the POA, it should be read along with the agreement to sell which was executed pursuant to sale consideration. The High Court while addressing the aforesaid submissions of the appellants held that though the GPA and the agreement to sell were executed by the same executant on the same day in favour of the same holder yet they cannot be treated as a single transaction. The detailed and comprehensive reading of the GPA and the agreement to sell would indicate that the contents of the GPA do not mention anything about the execution or purpose of executing the agreement to sell or vice versa. The relevant observations read as under:-

“…Even though it is observed that Exs.D-4 and D-5 were contemporaneous documents executed by Sri. Muniyappa @ Ruttappa in favour of Smt. A. Saraswathi, by that itself, it cannot be concluded that, the said Smt. A. Saraswathi had any interest in the Power of Attorney at Ex.D-4. It is for the reason that the said document at Ex.D-4 nowhere expressly mentions as to for what reason the executant was made to execute the said document and more particularly, the executant has nowhere whispered in it that the attorney has acquired any interest in the property mentioned in the said Power of Attorney. However, the said Power of Attorney – Smt. A. Saraswathi whether is having any interest under the said irrevocable Power of Attorney has to be gathered from the circumstance of the case and the position of law. If it can be concluded that she had acquired interest by virtue of Exs.D-4 and D-5, then probably, Section 202 of the Contract Act may come into picture. Otherwise, it would be Section 201 of the Contract Act that may come into operation.”

(iii) Thirdly, the principal contention of the appellants was that since the holder of POA had an interest in the property which is the subject-matter of the POA, the POA would not come to an end on the death of the executant by virtue of Section 202 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872 (for short, “the Contract Act”). The High Court held that executing a POA, including an irrevocable one or an agreement to sell for immovable property, does not automatically transfer any right or interest to the beneficiary, such as the attorney or agreement holder. By referring to the decisions of the High Court of Rajasthan in Prahlad & Ors. v. Laddevi & Ors., reported in 2007 SCC OnLine Raj 19 and the High Court of Karnataka in Wajid Pasha v. The Chairman, Bangalore Development Authority, reported in 2013 SCC OnLine Kar 10135, the High Court held that the purpose for which the GPA was executed had not been stated either in the GPA or the agreement to sell. It was observed that indisputably, the holder of POA did not enforce the agreement to sell against the legal representatives of the executant of the POA. After the death of the executant, the holder of POA transferred the Suit Property to her son i.e., the appellant no. 2, for a sale consideration of Rs. 84,000/- which was considerably higher than the amount she paid for the Suit Property to the original owner. Thus, the High Court held that the case of the appellants would not be covered by Section 202 of the Contract Act and that the POA did not create any right or interest in the favour of the holder of the POA. The relevant observations read as under:-

“38. Illustration (a) to Section 202 of the Contract Act is clear and applicable to those cases where the very purpose or execution of the Power of Attorney is to enable the Power of Attorney to get his/her entitlement paid to him/her. It is in that case, the attorney holder can be called as having interest in the General Power of Attorney executed in his/her favour, whereas, in the case on hand, as already observed above, the purpose for which the General Power of Attorney was executed by Sri. Muniyappa @ Ruttappa is nowhere made clear either in Ex.D-4 or Ex.D-5. Merely because they are contemporaneous documents, it cannot be inferred that the holder of the said agreement would get an interest under the General Power of Attorney so as to over come Section 201 of the Contract Act and fall within the scope of Section 202 of the same Act. This is clear in all the three judgments referred above which were relied upon by the learned counsel for the respondents. Rather in those situations, where the sale agreement holder though was put in possession and had already parted with some consideration, the remedy available to such agreement holder would be for enforcing the contract, specifically either as against the executant or his/her legal representatives.”

(iv) Fourthly, the High Court noted that the answering respondent not only established her lawful possession over the Suit Property as on the date of the institution of the suit but was also able to establish that there was interference with her peaceful possession by the appellants herein. The High Court held that the suit was not barred by limitation. It held that the Trial Court erred in holding so, as the suit was one for declaration and possession of the property. Therefore, as per Article 65 of the Act of 1963, the period of limitation would be twelve years.

15. In such circumstances, referred to above, the appellants are here before this Court with the present appeals.

C. SUBMISSIONS ON BEHALF OF THE APPELLANT(S)

16. Ms. Farhat Jahan Rehmani, the learned counsel appearing for the appellants submitted that the present case relates to the scope, interpretation and construction of the POA and the agreement to sell dated 04.04.1986 executed by the original owner in favour of holder. Hence, the limited question for our determination is whether the POA, which was coupled with interest is irrevocable as per Section 202 of the Contract Act or it stood terminated upon the death of the original owner as per Section 201 of the Contract Act?

17. Ms. Rehmani submitted that the fact of execution of the POA and the agreement to sell in favour of the holder by the original owner in exchange of sale consideration is not disputed. Since both the POA and the agreement to sell are in favour of the same person, they should be read together and construed harmoniously. The holder of POA executed the registered sale deed dated 01.04.1998 in favour of the appellant no. 2. Further, there is no challenge to the validity of the GPA and agreement to sell dated 04.04.1986 and the registered sale deed dated 01.04.1998. The GPA specifies that it had been executed for the purpose of the Suit Property. It specifically mentions that it is ‘irrevocable’ and the schedule to the GPA references the particulars of the Suit Property. The GPA read with the agreement to sell would indicate that it had been executed for a valid sale consideration, and possession of the Suit Property was also delivered to the holder of POA. Thus, she had an interest in the subject-matter of the agency being irrevocable. By placing reliance on Section 202 of the Contract Act, he submitted that where the agent himself has interest in the property which forms a subject-matter of the agency, the agency cannot be terminated to the prejudice of such interest of the agent. In the facts of the case, Section 202 of the Contract Act is applicable and not Section 201.

18. It was further submitted that the High Court erred in holding that the purpose for which the GPA and the agreement to sell was executed was not mentioned in either of the documents and therefore, even though the two documents are contemporaneous yet it cannot be inferred that the holder of the two documents would derive an interest in the subject-matter of the GPA. Ms. Rehmani asserted that it has to be inferred that the original owner executed the agreement to sell as a consequence of executing the GPA in favour of the holder, hence, the said POA is not irrevocable merely for the reason that in the said documents the purpose for executing the GPA and agreement to sell has not been mentioned.

19. While drawing the Court’s attention to para 26 of Suraj Lamp (supra), she submitted that the case of Suraj Lamp (supra) will not be applicable to the facts of the present case as in the present case the holder of GPA executed the registered sale deed on 01.04.1988 which was much prior in time. She further distinguished the decision in Prahlad (supra) and Wajid Pasha (supra) referred to and relied upon by the High Court on facts. Ms. Rehmani submitted that the High Court failed to consider that there was no challenge to the validity of the GPA, and the registered sale deed executed in favour of appellant no. 2. In such circumstances, a suit for injunction simpliciter filed by the answering respondent would not be maintainable. Further, the respondent no. 7 had no title in the Suit Property as the title had already been conveyed under the registered sale deed and there was no challenge to the same. The suit O.S. No. 4045/2008 filed by the appellants for declaration and possession ought to have been decreed.

20. In view of the aforesaid submissions, the counsel prayed that the impugned judgment passed by the High Court be set aside and appellants be declared to be the true owner of the Suit Property and grant possession thereof.

D. SUBMISSIONS OF BEHALF OF THE RESPONDENT(S)

21. Mr. Mahesh Thakur, the learned counsel appearing for the answering respondent submitted that an agreement of sale creates an interest against the vendor or his legal representatives and to enforce that interest the intended buyer is required to file a suit for specific performance by virtue of Section 40 of the Transfer of Property Act, 1882 (for short, “the TPA”). In view of Section 17 of the Registration Act, a property worth Rs. 100 or more cannot be transferred without registration. In the present case, the value of property is more than Rs. 100, therefore, the original owner could not have transferred the property merely by an agreement to sell or GPA or by executing both.

22. To buttress his aforesaid submission that such documents cannot pass on title, Mr. Thakur relied on the decision in Suraj Lamp (supra) to submit that by virtue of Section 54 of the TPA, an agreement to sell does not create any interest in or charge on such property. Further, a POA is not an instrument of transfer qua any right, title or interest in any immovable property. A sale by an agreement to sell or GPA will neither convey any title nor create any interest in an immoveable property. He relied on Wajid Pasha (supra) to submit that the contract of agency gets automatically terminated by death of either of the parties. As soon as the executant of POA dies, the right given to the agent comes to an end. Once the agency is terminated, the agent cannot act on the basis of the power granted to him under the GPA. He also placed reliance on Prahlad (supra) to submit that a POA granted by the donor to the donee is operative and effective only during the lifetime of the donor. Since the donor and done are in a relationship of master-agent a POA cannot stand after the death of the donor. He asserted that the principle of nemo dat quod non habet would apply meaning thereby that the holder of POA could not have passed a title that she did not possess.

23. Mr. Thakur further submitted that even if for the sake of argument, it is presumed that the GPA was coupled with interest and Section 202 of the Contract Act comes into operation, still it can apply only to an extent that the buyer can enforce the agreement against the vendor or his legal representatives for specific performance or for return of the sale consideration paid. Lastly, he submitted that it is not the case of the appellants that legal representatives of the original owner were aware about the transaction between their father and the holder of POA. Answering respondent now holds the position of a bona fide purchaser for valuable consideration.

24. In such circumstances referred to above, the counsel prayed that there being no merit in the present appeals, those may be dismissed.

E. ISSUES FOR CONSIDERATION

25. Having heard the learned counsel appearing for the parties and having gone through the materials on record, the following questions fall for our consideration:

a. Whether the agent, A. Saraswathi, by virtue of being a holder of the General Power of Attorney along with Agreement to Sell had any right, title or interest in the subject-matter of the agency, to execute the registered sale deed dated 01.04.1998 in favour of her son i.e., the appellant no. 2, after the death of the principal, on 30.01.1997?

b. Whether it was obligatory for the answering respondent to challenge the execution and validity of the General Power of Attorney and the Agreement to Sell dated 04.04.1986 and a further prayer to declare that the registered sale deed dated 01.04.1998 is invalid, non-est or illegal in O.S. 133/2007?

F. ANALYSIS

26. At the cost of repetition, we deem it necessary to state how the property exchanged hands on both sides. It is the case of the appellants that the original owner executed a GPA and agreement to sell in favour of the holder. Thereafter, the holder in her capacity as a holder of POA vide a registered sale deed sold the Suit Property to her son, appellant no. 2. On the other hand, it is the case of the respondents that after the death of the original owner, his heirs (respondent no. 1-6) sold the Suit Property to S. Sreenivasullu (respondent no. 7) vide a registered sale deed, thereafter, S. Sreenivasullu sold the Suit Property to C. Roopavathi (respondent no. 8) vide another registered sale deed. Lastly, C. Roopavathi vide a registered gift deed gifted the Suit Property to her daughter, J. Manjula (answering respondent).

i. Relationship between the Executant and Holder of General Power of Attorney

27. A power of attorney derives its basic principles from Chapter X of the Contract Act which provides for “Agency” along with Sections 1A and 2 respectively of the Powers of Attorney Act, 1882. Agency is a fiduciary relationship between two persons, where one explicitly or implicitly agrees that the other will act on their behalf to influence their legal relations with third parties, and the other similarly agrees to act in this capacity or does so based on an agreement. The relationship between the executant of a general power of attorney and the holder of the power is one of principal and agent. A principal is bound by the acts done by an agent or the contracts made by him on behalf of the principal. Likewise, power of attorney in the nature of contract of agency authorizes the holder to do acts specified by the executant, or represent the executant in dealings with third persons.

28. In the case of Syed Abdul Khader v. Rami Reddy & Ors., reported in (1979) 2 SCC 601, this Court held that the relation between the donor of the power and the donee of the power is one of the principal and agent having its genesis in a contract. It further observed that the term “agency” refers to the relationship in which one person has the authority or ability to establish legal relations between a principal and third parties. This relationship arises when a person, known as the agent, has the authority to act on behalf of another, called the principal, and agrees to do so. The relevant observations are reproduced hereinbelow:-

“10. The first contention of the appellant is that it was impermissible in law for three persons to jointly grant a power of attorney in favour of Defendant 34. Barring the ipse dixit of the learned counsel nothing was shown to us to make such a joint power impermissible in law. The relation between the donor of the power and the donee of the power is one of the principal and agent and the expression “agency” is used to connote the relation which exists where one person has an authority or capacity to create legal relations between a person occupying the position of principal and third parties. The relation of agency arises whenever one person called the agent has authority to act on behalf of another called the principal and consents so to act. The relationship has its genesis in a contract. If agency is the outcome of a contract between the principal and the agent, in order to show that three principals jointly constituting an agent by a deed called “Power of Attorney” was impermissible, provisions of Contract Act or the general law of contract should have been shown as having been violated by such a contract.

Nothing of the kind was pointed out to us. On the contrary, in Halsbury’s Laws of England, Vol. I, 4th Edn., para 726, the following proposition has been stated:

“Co-principals may jointly appoint an agent to act for them and in such case become jointly liable to him and may jointly issue him.”

We are in agreement with this view and, therefore, three principals could jointly appoint an agent.”

(Emphasis supplied)

29. In State of Rajasthan v. Basant Nahata, reported in (2005) 12 SCC 77, while dealing with the challenge to the constitutional validity of Section 22A of the Registration Act, it was held that a deed of power of attorney is a document of convenience empowering the agent to act for the principal or manage the affairs of the principal. The relevant observations are reproduced hereinbelow:

“Power of attorney

13. A grant of power of attorney is essentially governed by Chapter X of the Contract Act. By reason of a deed of power of attorney, an agent is formally appointed to act for the principal in one transaction or a series of transactions or to manage the affairs of the principal generally conferring necessary authority upon another person. A deed of power of attorney is executed by the principal in favour of the agent. The agent derives a right to use his name and all acts, deeds and things done by him and subject to the limitations contained in the said deed, the same shall be read as if done by the donor. A power of attorney is, as is well known, a document of convenience.

14. Besides the Contract Act, the Powers-of-Attorney Act, 1882 deals with the subject. Section 1-A of the Powers-of-Attorney Act defines power of attorney to include any instruments empowering a specified person to act for and in the name of the person executing it. Section 2 of the said Act reads, thus:

“2. Execution under power of attorney.—The donee of a power of attorney may, if he thinks fit, execute or do any instrument or thing in and with his own name and signature, and his own seal, where sealing is required, by the authority of the donor of the power; and every instrument and thing so executed and done, shall be as effectual in law as if it had been executed or done by the donee of the power in the name, and with the signature and seal, of the donor thereof.

This section applies to powers of attorney created by instruments executed either before or after this Act comes into force.”

Execution of a deed of power of attorney, therefore, is valid in law and subject to the provisions of the Act is not compulsorily registerable.”

(Emphasis supplied)

30. From the above exposition of law, it is settled that power of attorney is a creation of an agency by which the grantor/donor/executant authorizes the grantee/donee/holder/attorney to do the acts specified on his behalf, which will be binding on the executant as if the acts were done by him.

31. In the present case, the original owner, executant of the POA, holds the position of a principal. Whereas, the holder of the POA is an agent. There is no gainsaying in the fact that the original owner by executing the POA dated 04.04.1986 in favour of the holder entered into a principal-agent relationship with each other. We shall now proceed with an independent as well as combined reading of the GPA and the agreement to sell.

ii. Independent Reading of the General Power of Attorney and the Agreement to Sell

a. ‘Interest’ in Power of Attorney

32. It was submitted on behalf of the appellants that the GPA read with the agreement to sell categorically states that POA was executed for a consideration, and the possession of the Suit Property was delivered to the holder. It was further submitted that since both the documents were executed on the same day, in favour of the same person, they should be read together and construed harmoniously. It is because of this reason that POA holder (agent) has an interest in the subject-matter of the agency and the POA is coupled with interest which makes the agency irrevocable by virtue of Section 202 of the Contract Act.

33. Section 201 of the Contract Act prescribes various ways of revocation of authority given by the principal to his agent. A principal can terminate the contract of agency unless such revocation is precluded by Section 202 of the Contract Act. Section 202 of the Contract Act, as an exception to the general rule under Section 201, prescribes that where an agent has himself an interest in the property which forms the subject-matter of the agency, the agency cannot be terminated to the prejudice of such interest unless there is an express stipulation to the contrary.

34. Illustration (a) to Section 202 of the Contract Act states that A (principal) has given authority to B (agent) to sell A’s land, and to pay himself i.e., the agent, from the proceeds the debt which is due to him from A. Illustration (b) states that A (principal) has consigned 1,000 bales of cotton to B (agent), who has given an advance on the bales of cotton. Now, A wishes B to sell the cotton and recover his advance from the sale proceeds. In both the cases, A can neither revoke the authority nor agency will be terminated by his insanity or death. It is important to take a note that in both the cases, the agent has an interest vested in the subject-matter of the agency. The factum of interest or security of the agent, in both cases, does not imply that the agent’s right to remuneration constitutes an interest in the subject matter of the agency; rather, it extends beyond the mere advancement of remuneration or commission. Where POA is coupled with an interest, it metamorphosizes to an irrevocable agency unless expressly stated otherwise.

There an agent’s right to remuneration is not an interest in the subject-matter of the agency.

35. Therefore, the essentials of Section 202 of the Contract Act are, first, there shall be a relationship in the capacity of ‘principal and agent’ between the parties and secondly, there shall be agent’s interest in the subject-matter of the agency. If both the conditions are fulfilled the agency becomes irrevocable and cannot be terminated unilaterally at the behest of the principal. As the first condition is satisfied in the present case, we shall now proceed to examine whether from the reading of the GPA, the holder of POA had an interest in the subject matter of the agency, namely, the Suit Property.

36. We may quote an extract from Bowstead on Agency, 14th Edition, page 423 it stated as under:-

“(i) Where the authority of an agent is given by deed or for valuable consideration, for the purpose of effectuating any security, or of protecting or securing any interest of the agent, it is irrevocable during the subsistence of such security or interest. But it is not irrevocable merely because the agent has an interest in the exercise of it or has a special property in, or lien for advances upon, the subject matter of it, the authority not being given expressly for the purpose of securing such interest or advances;

(ii) Where a power of attorney, whenever created is expressed to be irrevocable and is given to secure a proprietary interest of the donee of the power, or the performance of an obligation owed to the donee, then, so long as the donee has that interest, or the obligation remains undischarged, the power is irrevocable;

(iii) Authority expressed by this article to be irrevocable is not determined by the death, insanity or bankruptcy of the principal, nor….. where the principal is an incorporated company, but its winding up or dissolution, and cannot be revoked by the principal without the consent of the agent.”

37. As far back as 1931, in Dalchand v. Seth Hazarimal & Ors., reported in 1931 SCC OnLine MP 57, the defendant-agent claimed that he had an interest in the cloth supplied to him by the plaintiff-principal for sale because according to the agent he was entitled to keep for himself any amount obtained by him as per the assigned rates. The court held that the agent had no interest in the property being sold or in the proceeds of sale until sale is complete. The relevant observations are reproduced hereinbelow:-

“5. For the plaintiff, Vishnucharya v. Ramchandra [[1881] 5 Bom. 253.], has been cited, in which it has been held that an agent for the collection of rents cannot be regarded as having an interest in the property merely because he is authorized to take his salary out of the rents. It is objected on behalf of the defendants that this decision runs directly contrary to Illus. (a), S. 202. But I find that a similar view has been taken in Lakhmiohand v. Chotooram [[1900] 24 Bom. 403.], in which the facts more closely resemble those of the present case and it was held that the interest which an agent has in effecting a sale and the prospect of remuneration to arise therefrom is not such an interest as would prevent the termination of the agency.

6. I am in respectful agreement with the decisions in these two Bombay cases. They and the case before me are clearly distinguishable from the case stated in Illus. (a), Section 202 of the Contract Act. In the illustration, the principal was under a liability to the agent quite apart from the contract of agency, and the authority given to him to sell the principal’s land was by way of security for the discharge of that liability. In the present case, the agent had no interest in the property to be sold or in the sale proceeds thereof until a sale had been actually effected, and revocation of the agency, before sale had been effected, deprived him of nothing that had accrued to him.”

(Emphasis supplied)

38. In the case of Palani Vannan v. Krishnaswami Konar, reported in 1945 SCC OnLine Mad 119, the decree-holder had executed a POA authorizing the holder to execute the decree. Later, the executant revoked the POA through a notice. The question before the court was whether the notice revoking the authority was valid in law or not. The court held that the POA was not coupled with interest as the object of the POA was not securing any interest of the agent. It held that the primary object of the POA was to recover the fruits of the decree on behalf of the principal despite the fact that the agent’s remuneration was fixed to be drawn from the proceeds of the decree. The relevant observations are reproduced hereinbelow:

“It is only necessary to refer to one further decision, Frith v. Frith [[1906] A.C. 254.], in which the Judicial Committee discuss the general position relating to these matters. Their Lordships point out that in what is known as Carmichael’s case [[1896] 2 Ch. 643.]:

“The donor of the power, for valuable consideration, conferred upon the donee, authority to do a particular thing in which the latter had an interest, namely, to apply for the shares of the Company which the donee was promoting for the purpose of purchasing his own property from him, and the donor sought to revoke that authority before the benefit was reaped.”

The effect of all these cases appears to be stated accurately in Bowstead on the Law of Agency, Eighth Edition, page 456. It is stated (Article 138):

“Where the authority of an agent is given for the purpose of effectuating any security, or of protecting or securing any interest of the agent, it is irrevocable during the subsistence of such security or interest.”

–xxx–

My view of this document is as follows. I think its primary object was to recover on behalf of the principal the fruits of his decree. It contained incidentally a provision for the employment of the agent, Vedavyasachar, in order to realize that decree. It provides that his remuneration is to be one-half of the proceeds. It contains an indemnity clause against any out-of-pocket expenses which he is entitled also to recover from the amount of the decree. But the object of the power-of-attorney is not for the purpose of protecting or securing any interest of the agent. I think that part of the agreement is purely incidental. There is, however, another feature of this document which seems to me to be conclusive against the appellants. The last words,

“I shall not for any reason whatever, cancel without your permission this authority which I have given to you, without paying the amount expended by you and without giving the aforesaid relief for your trouble”,

seem to me to make express provision for the revocation of the above power. It can be done in two ways, (a) by consent, for that is what I understand “your permission” to mean, and (b) if that permission is withheld, on payment by the principal of all out-of-pocket expenses and also remuneration for his services. With regard to remuneration, the wording is vague, “without giving the aforesaid relief for your trouble”.

(Emphasis supplied)

39. To the same effect is the decision of High Court of Delhi in Shri Harbans Singh v. Smt. Shanti Devi, reported in 1977 SCC OnLine Del 102. The High Court while dealing with the question of whether the powers of attorney executed by the appellant were cancelled validly, laid down the conditions of irrevocability of a contract of agency as, (i) authority to agent given for valuable consideration; (ii) such valuable consideration was given for the purpose of effectuating a security or protecting or securing the interest of the agent; (iii) agency not being irrevocable merely because the agent has some interest in carrying it out or holds a special right, such as a lien or advance, over its subject matter. Thus, the agency has to be specifically meant to secure the agent’s benefit or interest. It further observed that the interest of the agent can be inferred from the language of the document or from the course of business between the principal and agent. The observations are reproduced hereinbelow:-

“All the conditions of irrevocability are satisfied in the present case. The authority to the agent was given for valuable consideration which proceeded from the respondent. It was given for the purpose of effectuating a security or protecting or securing the interest of the agent. For, the only purpose of the agency was to ensure and secure the performance of the contract by the appellant in favour of the respondent for whom Shri Gulati was acting as the husband and the nominee and, therefore, a representative or an agent. Where the performance of the agency is not to secure the interest or the benefit of the agent then the agency is not irrevocable merely because the agent has an interest in the exercise of it or has a special property in or lien for advances upon the subject-matter of it.”

(Emphasis supplied)

40. In the present case, it is evident from para 1 of the GPA executed by the original owner in favor of the holder that the POA was to look after, maintain, manage the Scheduled Property. Para 2 states that the attorney can enter into any agreement with any person with respect to the Scheduled Property for any amount, receive advance amount, to execute deeds in favor of such persons, issue proper discharge. Para 3 states that attorney has the power to apply for transfer of khata and to pay all future taxes and receive receipts. Further, para 4 states that the attorney can apply for sanctioning of plan for the purpose of construction, utilize the Scheduled Property as the holder deems fit and receive all profits therefrom. Para 5 states that the attorney has the power to represent the holder in all Government Offices and do all things connected. Para 6 states that the attorney can pursue matters in courts, give evidence, obtain decree, execute the same. Further, para 7 states that the Scheduled Property is in owner’s peaceful possession and enjoyment. Lastly, para 8 states that the attorney is generally entitled to do all acts required in respect of the Suit Property which are not specifically mentioned and that the GPA is irrevocable.

b. Nature of Power of Attorney

41. It is now appropriate to analyze the nature of the GPA, specifically whether it is general or special. While construing a document, a reader should not go by the title to the document or the nomenclature of the document. In such a case, the court is endowed with a duty to see the contents of the document and intention of the parties which can be gathered from the terms of the document and/or from circumstances under which the document was entered into. The intention of the parties can be ascertained from the language used by the parties. A document has to be seen as a whole.

42. The import of the word “general” in a POA refers to the power granted concerning the subject matter. The test to determine the nature of POA is the subject matter for which it has been executed. The nomenclature of the POA does not determine its nature. Even a POA termed as a ‘general power of attorney’ may confer powers that are special in relation to the subject matter. Likewise, a ‘special power of attorney’ may confer powers that are general in nature concerning the subject matter. The essence lies in the power and not in the subject-matter.

43. In Halsbury, Vol. 1, at page 151, the author defines special and general agents, the definition of general agent has been stated as follows:

“A general agent is one who has authority, arising out of and in the ordinary course of his business or profession, to do some act or acts on behalf of his principal in relation thereto; or one who is authorised to act on behalf of the principal generally in transactions of a particular kind or incidental to a particular business.”

44. A three-Judge Bench of this Court settled the rules of interpretation applicable to power of attorney in Timblo Irmaos Ltd., Margo v. Jorge Anibal Matos Sequeira, reported in (1977) 3 SCC 474. It was held that words used in a POA must be interpreted in the context of the whole; the purpose of the powers conferred must then be examined through the circumstances in which it was executed; and finally, necessary powers must be implied. The relevant observations are reproduced hereinbelow:-

“11. We think that perhaps the most important factor in interpreting a power of attorney is the purpose for which it is executed. It is evident that the purpose for which it is executed must appear primarily from the terms of the power of attorney itself, and, it is only if there is an unresolved problem left by the language of the document, that we need consider the manner in which the words used could be related to the facts and circumstances of the case or the nature or course of dealings. We think that the rule of construction embodied in proviso 6 to Section 92 of the Evidence Act, which enables the Court to examine the facts and surrounding circumstances to which the language of the document may be related, is applicable here, because we think that the words of the document, taken by themselves, are not so clear in their meanings as the learned Judicial Commissioner thought they were.

–xxx–

13. The learned Judicial Commissioner had, in our opinion, overlooked several well-known rules of interpretation: firstly, that, a word used in a document has to be interpreted as a part of or in the context of the whole; secondly, that, the purpose of the powers conferred by the power of attorney have to be ascertained having regard to the need which gave rise to the execution of the document, the practice of the parties, and the manner in which the parties themselves understood the purpose of the document; and, thirdly, that, powers which are absolutely necessary and incidental to the execution of the ascertained objects of the general powers given must be necessarily implied.”

(Emphasis supplied)

45. Further, a mere use of the word ‘irrevocable’ in a POA does not make the POA irrevocable. If the POA is not coupled with interest, no extraneous expression can make it irrevocable. At the same time, even if there is no expression to the effect that the POA is irrevocable but the reading of the document indicates that it is a POA coupled with interest, it would be irrevocable. The principles of construction of a POA termed as ‘irrevocable’ was explained in Manubhai Prabhudas Patel v. Jayantilal Vadilal Shah, reported in 2011 SCC OnLine Guj 7028. The relevant observations are reproduced below:-

“12. I am of the view that while construing a document, it is necessary to determine the real intention of the parties. The mere form in which document is couched is immaterial. The intention of the parties has to be gathered from the terms of the documents themselves and from such of the surrounding circumstances, as later required to show in what manner the language of the document is related to the existing fact. It is very difficult task to know the intention of the parties on the basis of the recital of the document. But, the Court can rely safely on the language of the document, the language, which has been used by the parties to manifest the intention of the parties. If the Court goes on extraneous evidence, that may lead to more difficulty and confusion. But, there are certain principles to be borne in mind. The first principle is, the mere saying that the power of attorney is an irrevocable power of attorney coupled with interest is not the end of the matter. The Court, can clearly say that the document, though, is styled as an irrevocable power of attorney is not in substance a power coupled with interest so as to make it an irrevocable power of attorney. At the same time, even if there is no title to show that the power is an irrevocable power, but, the substance of the entire document would suggest that the same is an irrevocable power coupled with interest. Therefore, a document has to be construed as a whole. A stray sentence here and there cannot be picked out to construe a document. To understand the tenor of the document and the intention of the parties, it has to be read as a whole. The real intention of the parties has to be covered not merely from what ex-facie is stated in the document, but, from the totality of the recitals in the document. At this stage, I may quote with profit a very lucid judgment rendered by learned Single Judge of Madras High Court explaining the general principles regarding the construction of power of attorney. In case of Anantha Pillai v. Ratiinasabapatiiy Mudaliar, reported in 1968 (2) MLJ 574, Ismail, J. (as he then was), held thus:

“The general principles regarding the construction of power of attorney are well settled. Powers of attorney must be strictly construed as giving only such authority as they confer expressly or by necessary implication. Where an act purporting to be done under the power of attorney is challenged as being in excess of the power, it is necessary to show that on a fair construction of the whole instrument the authority in question is to be found within the four corners of the instrument either by express terms or by necessary implication. Some of the principles governing the construction of a power of attorney are:(1) the operative part of the deed is controlled by the recitals, (2) where an authority is given to do particular acts, followed by general words, the general words are restricted to what is necessary for the performance of the particular acts, (3) the general words do not confer general powers but are limited to the purpose for which the authority is given and are construed as enlarging the special powers only when necessary for that purpose; (4) a power of attorney is construed so as to include all medium powers necessary for its effective execution. Bearing these general principles in mind the question for consideration is whether the power of attorney in this case authorised the first defendant to enter into an agreement to sell or authorised him to execute a sale-deed….””

(Emphasis supplied)

46. Applying the above exposition of law in the facts of the present case, it is evident from the tenor of POA that is not irrevocable as it was not executed to effectuate security or to secure interest of the agent. The holder of POA could not be said to have an interest in the subject-matter of the agency and mere use of the word ‘irrevocable’ in a POA would not make the POA irrevocable. The High Court was right in holding that the holder did not have any interest in the POA. When the High Court observes that the power of attorney does not explicitly state the reason for its execution, it implies that its nature is general rather than special.

47. It is a settled law that a transfer of immovable property by way of sale can only be by a deed of conveyance. An agreement to sell is not a conveyance. It is not a document of title or a deed of transfer of deed of transfer of property and does not confer ownership right or title. In Suraj Lamp (supra) this Court had reiterated that an agreement to sell does not meet the requirements of Sections 54 and 55 of the TPA to effectuate a ‘transfer’.

48. From the independent reading of the POA and the agreement to sell, the submissions of the appellants fail on two grounds, first, the POA is general in nature and does not secure agent’s right in the subject-matter of the agency, and secondly, an agreement to sell simpliciter does not confer ownership in the immovable property so as to transfer a better title to anyone else.

iii. Combined Reading of the General Power of Attorney and the Agreement to Sell

49. The issue at hand may also be looked at from another angle. The appellants have submitted that that since the GPA and the agreement to sell were executed by the same person in favour of the same beneficiary, it ought to have been read together.

50. Here, we deem it appropriate to take note of Sections 17 and 49 of the Registration Act respectively. The provisions have been reproduced hereinbelow:-

“17. Documents of which registration is compulsory.—(1) The following documents shall be registered, if the property to which they relate is situate in a district in which, and if they have been executed on or after the date on which, Act No. XVI of 1864, or the Indian Registration Act, 1866, or the Indian Registration Act, 1871, or the Indian Registration Act, 1877, or this Act came or comes into force, namely:—

(a) instruments of gift of immovable property;

(b) other non-testamentary instruments which purport or operate to create, declare, assign, limit or extinguish, whether in present or in future, any right, title or interest, whether vested or contingent, of the value of one hundred rupees and upwards, to or in immovable property;

(c) non-testamentary instruments which acknowledge the receipt or payment of any consideration on account of the creation, declaration, assignment, limitation or extinction of any such right, title or interest; and

(d) leases of immovable property from year to year, or for any term exceeding one year, or reserving a yearly rent;

(e) non-testamentary instruments transferring or assigning any decree or order of a Court or any award when such decree or order or award purports or operates to create, declare, assign, limit or extinguish, whether in present or in future, any right, title or interest, whether vested or contingent, of the value of one hundred rupees and upwards, to or in immovable property:

Provided that the [State Government] may, by order published in the [Official Gazette], exempt from the operation of this sub-section any lease executed in any district, or part of a district, the terms granted by which do not exceed five years and the annual rents reserved by which do not exceed fifty rupees.

(1A) The documents containing contracts to transfer for consideration, any immovable property for the purpose of section 53A of the Transfer of Property Act, 1882 (4 of 1882) shall be registered if they have been executed on or after the commencement of the Registration and Other Related laws (Amendment) Act, 2001 (48 of 2001) and if such documents are not registered on or after such commencement, then, they shall have no effect for the purposes of the said section 53A.

(2) Nothing in clauses (b) and (c) of sub-section (1) applies to—

(i) any composition deed; or

(ii) any instrument relating to shares in a joint stock Company, notwithstanding that the assets of such Company consist in whole or in part of immovable property; or

(iii) any debenture issued by any such Company and not creating, declaring, assigning, limiting or extinguishing any right, title or interest, to or in immovable property except in so far as it entitles the holder to the security afforded by a registered instrument whereby the Company has mortgaged, conveyed or otherwise transferred the whole or part of its immovable property or any interest therein to trustees upon trust for the benefit of the holders of such debentures; or

(iv) any endorsement upon or transfer of any debenture issued by any such Company; or

(v) any document other than the documents specified in sub-section (1A) not itself creating, declaring, assigning, limiting or extinguishing any right, title or interest of the value of one hundred rupees and upwards to or in immovable property, but merely creating a right to obtain another document which will, when executed, create, declare, assign, limit or extinguish any such right, title or interest; or

(vi) any decree or order of a Court [except a decree or order expressed to be made on a compromise and comprising immovable property other than that which is the subject-matter of the suit or proceeding]; or

(vii) any grant of immovable property by [Government]; or

(viii) any instrument of partition made by a Revenue-Officer; or

(ix) any order granting a loan or instrument of collateral security granted under the Land Improvement Act, 1871, or the Land Improvement Loans Act, 1883; or

(x) any order granting a loan under the Agriculturists, Loans Act, 1884, or instrument for securing the repayment of a loan made under that Act; or

(xa) any order made under the Charitable Endowments Act, 1890 (6 of 1890), vesting any property in a Treasurer of Charitable Endowments or divesting any such Treasurer of any property; or

(xi) any endorsement on a mortgage-deed acknowledging the payment of the whole or any part of the mortgage-money, and any other receipt for payment of money due under a mortgage when the receipt does not purport to extinguish the mortgage; or

(xii) any certificate of sale granted to the purchaser of any property sold by public auction by a Civil or Revenue-Officer.

Explanation.—A document purporting or operating to effect a contract for the sale of immovable property shall not be deemed to require or ever to have required registration by reason only of the fact that such document contains a recital of the payment of any earnest money or of the whole or any part of the purchase money.

(3) Authorities to adopt a son, executed after the 1st day of January, 1872, and not conferred by a will, shall also be registered.”

–xxx–

49. Effect of non-registration of documents required to be registered.—No document required by any provision of the Transfer of Property Act, 1882 (4 of 1882)], to be registered shall—

(a) affect any immovable property comprised therein, or

(b) confer any power to adopt, or

(c) be received as evidence of any transaction affecting such property or conferring such power, unless it has been registered:

[Provided that an unregistered document affecting immovable property and required by this Act or the Transfer of Property Act, 1882 (4 of 1882), to be registered may be received as evidence of a contract in a suit for specific performance under Chapter II of the Specific Relief Act, 1877 (3 of 1877) *** or as evidence of any collateral transaction not required to be effected by registered instrument.]”

51. Section 17(1)(b) prescribes that any document which purports or intends to create, declare, assign, limit or extinguish any right, title or interest, whether vested or contingent, of the value of one hundred rupees and upwards to or in immovable property is compulsorily registerable. Whereas, Section 49 prescribes that the documents which are required to be registered under Section 17 will not affect any immovable property unless it has been registered.

52. The aforesaid has been emphatically laid down by this Court in Shyam Narayan Prasad v. Krishna Prasad & Ors., reported in (2018) 7 SCC 646. The relevant observations are reproduced hereinbelow:-

“20. Section 17(1)(b) of the Registration Act mandates that any document which has the effect of creating and taking away the rights in respect of an immovable property must be registered and Section 49 of the Registration Act imposes bar on the admissibility of an unregistered document and deals with the documents that are required to be registered under Section 17 of the Registration Act. Since, the deed of exchange has the effect of creating and taking away the rights in respect of an immovable property, namely, RCC building, it requires registration under Section 17. Since the deed of exchange has not been registered, it cannot be taken into account to the extent of the transfer of an immovable property.”

(Emphasis supplied)

53. Even from the combined reading of the POA and the agreement to sell, the submission of the appellants fails as combined reading of the two documents would mean that by executing the POA along with agreement to sell, the holder had an interest in the immovable property. If interest had been transferred by way of a written document, it had to be compulsorily registered as per Section 17(1)(b) of the Registration Act. The law recognizes two modes of transfer by sale, first, through a registered instrument, and second, by delivery of property if its value is less than Rs. 100/-.

54. This principle was recently elaborated by the High Court of Karnataka in Channegowda & Anr. v. N.S. Vishwanath & Ors., reported in 2023 SCC OnLine Kar 153. The relevant portion is reproduced as under:-

“14. An attempt is made on behalf of the plaintiffs to contend that the second plaintiff has sold the property as a General Power of Attorney Holder and not as a title holder.

It is argued that the Power of attorney is not compulsorily registrable. The submission is noted with care. Suffice it to note that a deed of power of attorney is not one of the instruments specified under Section 17 of the Registration Act compulsorily registrable. However, if a power has been created empowering the attorney to sell the property i.e., if a document that gives a right to the attorney holder to sell the immovable property, then it would be a document creating an interest in immovable property, which would require compulsory registration. In the present case, the General Power of Attorney alleged to have been executed by defendants 1 to 3 in favor of the second plaintiff is coupled with interest i.e., power of alienation is conferred but it is not registered. The Apex Court in the SURAJ LAMP’s case has held that the General Power of Attorney Sale, or Sale Agreements/Will do not convey title and do not amount to transfer, nor can they be considered valid modes of transfer of immovable property. Therefore, it can be safely concluded that the declaration of facts/statement of facts (affidavit) and General Power of Attorney do not convey title. They are inadmissible in evidence.”

(Emphasis supplied)

55. The High Court rightly held that even though the GPA and the agreement to sell were contemporaneous documents executed by the original owner in favour of the holder, this alone cannot be a factor to reach the conclusion that she had an interest in the POA. Thus, even though the GPA and the agreement to sell were contemporaneous documents executed by the original owner in favour of the same beneficiary, this cannot be the sole factor to conclude that she had an interest in the subject-matter. Even if such an argument were to persuade this Court, the document must have been registered as per Section 17(1)(b) of the Registration Act. In the absence of such registration, it would not be open for the holder of the POA to content that she had a valid right, title and interest in the immovable property to execute the registered sale deed in favour of appellant no. 2.

56. The practice of transferring an immovable property vide a GPA and agreement to sell has been discouraged by the following observations of this Court in Suraj Lamp (supra). The relevant observations are reproduced hereinbelow:-

“24. We therefore reiterate that immovable property can be legally and lawfully transferred/conveyed only by a registered deed of conveyance. Transactions of the nature of “GPA sales” or “SA/GPA/will transfers” do not convey title and do not amount to transfer, nor can they be recognised or valid mode of transfer of immovable property. The courts will not treat such transactions as completed or concluded transfers or as conveyances as they neither convey title nor create any interest in an immovable property. They cannot be recognised as deeds of title, except to the limited extent of Section 53-A of the TP Act. Such transactions cannot be relied upon or made the basis for mutations in municipal or revenue records. What is stated above will apply not only to deeds of conveyance in regard to freehold property but also to transfer of leasehold property. A lease can be validly transferred only under a registered assignment of lease. It is time that an end is put to the pernicious practice of SA/GPA/will transactions known as GPA sales.”

(Emphasis supplied)

iv. Effect of Suit for Injunction simpliciter

57. The appellants submitted that the answering respondent had not challenged the validity of the GPA and the agreement to sell dated 04.04.1986 executed in favour of the holder and registered sale deed dated 01.04.1998 executed in favour of appellant no. 2. The appellants’ submission does not hold good, as the absence of a separate suit for declaration or even a specific prayer to that effect does not alter the legal position of either party in the facts of this case. The legal standing of both parties remains unaffected, for want of a distinct challenge to the instruments in question.

58. Where the question of title is “directly and substantially” in issue in a suit for injunction, and where a finding on an issue of title is necessary for granting the injunction, with a specific issue on title raised and framed, a specific prayer for a declaration of title is not necessary. As a result, a second suit would be barred when facts regarding title have been pleaded and decided by the Trial Court. In the present suit, the findings on possession rest solely on the findings on title. The Trial Court framed a categorical issue on the ownership of the appellants herein. To summarize, where a finding on title is necessary for granting an injunction and has been substantially dealt with by the Trial Court in a suit for injunction, a direct and specific prayer for a declaration of title is not a necessity.