Abheek Barua

♦ The reason that the “Turkey Crisis” has reverberated across the financial markets is not so much due to the problems specific to Turkey (default on its loans from offshore banks are not enough to precipitate a global financial crisis) but also because it has brought other risks back on the table. One of them is the possibility of a financial crisis emanating from mainland China. This isn’t surprising given that the elevation in trade tensions between the US and China has dominated the headlines in recent months.

♦ Why the fear of a financial crisis? The severity of the sell-off in China’s equity and foreign exchange markets over the past couple of months and the gravity of the external (prospects of a protracted trade war with the US) and domestic problems (its mounting debt pile) weighing on the Chinese economy have once again become a focal point of market anxiety with unsettling flashbacks to the 2015 crisis. The onshore renminbi has plunged 6.2% YTD against the dollar compared with 5% during the six-month-long sell-off that followed the surprise devaluation of the currency in August 2015. The CSI 300 index of large-cap stocks listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges, meanwhile, has fallen more than 19% YTD, marking it one of the worst-performing equity market globally this year.

♦ There have always been two divergent views and camps on China’s future. One camp has over the past couple of decades predicted imminent implosion in its banks, housing market or its tightly controlled asset market. The other camp has believed that China has both the capacity to muddle through and a government ready to pull out all stops to battle a looming crisis. We share the views of the second camp and believe that China is unlikely to face a full-blown financial crisis emerging either from the recent sell-off across Chinese asset classes or from the fallout of the trade war.

♦ For one, China this time around is in a better macroeconomic shape than it was during its asset market turmoil of 2015-16. Capital outflow that fuelled the sharp devaluation of the Yuan in 2015 is more moderate this time around. Besides there is a greater acknowledgement of the fact that the slowdown in China’s economy is at least partly due to the outcome of a shift in policy in favour of containing debt and active deleveraging of overstretched balance sheets (which is the most desirable from a long term perspective) and not just a sharp cyclical downturn.

♦ Secondly, the markets have always tended to underestimate the fact that the Chinese government, at the end of the day, has significant control of its economy and possesses massive financial resources, which it can unleash should the need arise. For instance, China has responded to the current trade war by providing new but targeted fiscal stimulus, including tax breaks, which has partly helped calm the financial markets.

♦ Again, the data on the trade relationship between the US and China might at first glance exaggerate the force of the impact on China. If one digs deeper and looks at value addition rather than the value of the final goods exports, the extent of the hit might be more limited.

♦ That said, we are by no means making the claim that China will be completely immune to the looming trade war. In fact it seems to be on the back-foot and open to concessions. The removal of U.S. crude oil (an item whose weight in the basket of US exports to China has been growing rapidly) from goods targeted by the Chinese tariffs perhaps confirms the fact that it wants to avoid an all-out brawl. In June, U.S. crude exports to China had risen to 15 million barrels, the highest volume in data going back to 19961.

♦ Investors’ concerns about the Chinese economy get exacerbated by its age-old large debt problem and a lurking risk in the form of rapidly rising household debt. There is also a worry among market participants about the possibility of a one-off engineered devaluation in the Yuan and a 2015 style panic in the financial markets. While we duly address these risks in our report, we also highlight several comfort factors, which, we think, could ease the severity of the potential impact caused by these risk factors.

♦ In our analysis, we also draw attention to the fact that the headline growth rate of 6.7 – 6.9% growth rate for the whole economy masks considerable divergence among China’s 31 regions. While this may seem rather inconsequential, what is critical is that companies are taking their investment and business decisions keeping this divergence in mind. This attempt to match effort to opportunity, in our opinion, bodes well for the economy going ahead.

♦ Overall, our assessment is that though there is a concern about China’s growth and markets, investors may be getting unduly pessimistic. Most of the market participants still expect a GDP growth of 6.5% for 2018. China’s policymakers accept that the trade war is real and could affect the economy adversely, and have already started to cushion the economy. The tilt is towards a more active and targeted fiscal policy instead of taking a detour from its financial reforms (particularly deleveraging), at least for now. The risk of an old style credit push and a fiscal binge that could set its financial sector reform back by years if not decades is low in our opinion.

♦ Going forward, while some depreciation in the CNY is possible, a major engineered devaluation is not expected given its FX debt pile, the CNY’s entry into the SDR basket and the possibility of a major run on the currency if investors panic and move funds offshore in a herd.

First things first, how the ongoing row with the US could impact China

China and the US have implemented several rounds of tit-for-tat tariffs on each other goods since the start of the year. In the recent round, the US has imposed a 25% tariff on another $16 billion worth of Chinese goods to be implemented starting today, to which China has responded likewise. Separately, China has proposed to put additional tariffs on 5,207 U.S. goods worth $60 billion, ranging from liquefied natural gas to some aircraft. This is in response to the US’s proposal to raise the rate of threatened tariffs on $200bn worth of Chinese exports to 25%, up from an original plan of 10%. These tariffs could take effect as early as next month.

This brings the value of trade threatened by Chinese potential tariffs to $110bn, compared with $130bn worth of goods that China imported from the US last year. The US is targeting $250bn worth of Chinese imports, out of a total of $505bn in 2017. Clearly, the US has more leeway here to up the ante and announce further tariffs on the remaining $255 bn worth of Chinese imports.

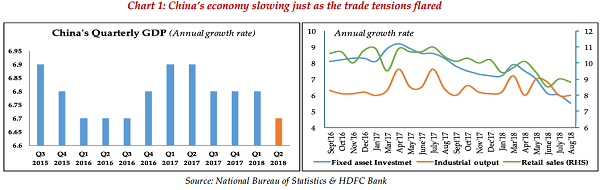

Concerns are mounting that a deepening trade war with the US is likely to further contribute to an already slowing growth scenario (Chart 1). Market estimates show that tariffs on the entire ~ USD505 billion worth of Chinese exports to the US could shave off 0.5 – 1.5% of China’s growth. Moreover, the subsequent hit to exporting companies (particularly smaller ones), plus the reverberation from the financial market correction, could amplify the second-order shock.

Yet there are several comforts

- The Chinese economy does not appear to be quite as exposed to exports to the US as the $505 billion figure suggests! The most important but underestimated point is that even though the Chinese exports to the US amount to be about 4.0% of GDP, the figure overstates China’s true exposure, as an exported final product often has value added by multiple countries along the way. For instance, data from the OECD shows that China has a foreign content share of over one third in its exports (second only to Korea in G-20) and that China’s trade surplus with the U.S. was one-third smaller in 2011 when measured in value added terms compared to it being measured in gross exports terms. Admittedly, much has changed since 2011 and China has moved up the value chain ladder. We, however, believe that it is safe to assume that China isn’t exposed to all of the $505 bn worth of exports to the US in value added terms.

- Limited ammunition in the trade war? While a tit-for-tat math doesn’t work out to be in China’s favour, China could resort to other ways to retaliate. A highly likely scenario is to target US companies operating out of China. To put things in perspective, US goods and services produced and sold in China in 2015 (the most recent year for which data is available) totaled $223 billion, far exceeding US exports to China of $150 billion in the same year. China might tax certain businesses, slow down custom clearances for their imports, implement anti-monopoly investigations or use health and safety checks as a way of temporarily shutting them down.

For instance, last year, Beijing decimated S. Korean retailer Lotte’s business in China after the company sold land to the Seoul government for an anti-missile system opposed by Chinese leaders.

- Also open to retaliation are services such as engineering and logistics in which the U.S. runs a trade surplus. Its services trade surplus with China hit $38bn in 2016.

- Moreover, any impact on the economy is likely to be staggered and could partially be compensated by a targeted fiscal policy – recent measures include a tax cut on R&D expenditures and easing of restrictions on banks’ issuance of financial bonds for small local firms.

Overall, we think that while tariffs could slowdown growth in Chinese exports and thereby the economy, the hit is unlikely to be large enough to cause the $12 trillion economy to destabilize completely. The risk is of course that in an effort to shore up the economy, market reforms and the much needed deleveraging could take a back-seat.

A list of China risks

1. Precarious debt levels – The speed and composition of China’s debt build-up has been an enduring risk over the past decade and has driven massive risk-off episodes in its asset markets. For instance, since the global financial crisis in 2008, China’s non-financial debt has jumped 120% to about 250% of GDP, out of which, the property sector and related industries accounted for half of the new debt while shadow banking contributed to 30%. Two-thirds of corporate debt is owed by Chinese SOEs, with SOE debt standing at 115% of GDP. The IMF anticipates that by 2020 China’s domestic credit to GDP ratio will rise to 300%. This highlights the magnitude of the reform challenge particularly in lightening the balance sheets of Chinese’s firms

2. A surge in corporate defaults – With this large outstanding leverage with the Chinese corporates, risks of defaults and the financial instability that these can potentially cause have also increased. According to figures from China Central Depository and Clearing Company, more than 10 companies, several of them listed, from a variety of industries have defaulted on 15 bonds worth more than 12.8 billion yuan (US$2 billion in 2018). Non-performing loans, though, officially are below 2%, exceed 20% as per unofficial estimates.

That said, the credit discipline is expected to be divergent among sectors due to varying industry dynamics and the policy mix. Sectors that look promising are China’s consumer (led by online retailing), technology, healthcare (best performing sector in Q1) and services sectors (to benefit from the structural change away from manufacturing.

Although this remains a risk going forward, missed bond payments in China (~1% of value of China’s corporate bond market) are still remarkably low as compared to other EMs (on average about 4%).

3. Property price downturn risk – While China’s household debt at 48% of GDP in 2017 may not seem high in absolute terms, its rise in combination with property reflation raises some red flags. For instance, in 2017, while annual property sales hit 16% of GDP ($2 trillion) compared with 10% of GDP in 2008, household debt measured against urban disposable income, rose to 1.4x from 0.6x. If this pace is sustained going forward, property reflation and household debt may reach uncomfortable levels. 2

4. Clogged transmission of funds – Amid an anticipated buildup of stress in certain sectors, various media reports suggest that Chinese banks are increasingly not willing to lend (especially to cash-strapped smaller firms) or buy risky bonds. While the PBoC has begun softening rules to encourage lending, financing hasn’t picked up much. Admittedly, this is also partly due to the success of government’s campaign to cut financial risk. That said, there is need to ensure that SMEs do not get completely strangulated by the lack of funds.

5. Yuan Decline: A matter of concern but not engineered – The yuan’s sharp depreciation against the dollar over the summer spooked some investors who see similarities with China’s currency devaluation in 2015 (the PBoC devalued the yuan on 11th August by 1.9% against the USD followed by a second devaluation by another 1.6% the next day). We, however, believe that it was more a combination of dollar rally, negative impact of protectionist pressures and limited intervention by the PBoC. The PBoC recent RRR hike on FX forwards show that the authorities are not encouraging yuan weakness. Also, if the PBoC was indeed intervening heavily, FX reserves would have fluctuated with the change in the CNY, which hasn’t been the case.

Going forward, while we factor in some depreciation, a major engineered devaluation is not expected

- Firstly, because it would also increase the servicing cost for China on its huge external debt ($1.71 trillion as of end 2017).

- Secondly, a big, intentional devaluation could incite herd behavior that could potentially destabilize China’s financial system and shatter the stable currency regime that the PBoC has worked hard to construct.

- Thirdly, competitive devaluation would also not go down well with the IMF as RMB is now part of the IMF’s SDR basket

What are the likely comforts?

1. An active fiscal policy: The Chinese government has been combating the slowdown pressures using targeted tax cuts and spending proposals (rather than initiating big-ticket stimulus projects) to encourage consumption than investment. For instance, while the government has tightened financing rules for shanty town redevelopments, it has accelerated government spending on environmental protection and science and technology.

While the Chinese government has set a lower fiscal deficit target of 2.6% of GDP for 2018, than from the 2017 target of 3.0% of GDP, it has enough ammunition in the second half to counter any slowdown with only 30% of the total budgeted deficit of 2.38 trillion yuan being reached by end of June. In addition, the 1.35 trillion-yuan special bond quota — part of a separately managed budget outside the annual deficit ratio — has barely been tapped by local governments this year, leading to ample room for selective tax cuts and support to the affected export oriented industries.

2. Accommodative credit policy: The People’s Bank of China has cut reserve ratios for banks three times this year, seeking to pump liquidity into targeted sectors such as small and rural firms. However, it maintains its “prudent and neutral” monetary policy stance, ruling out any broad-based easing.

While, with this, inter-bank borrowing costs have fallen significantly and the money multiplier has risen to a record high, new credit supply has expanded only modestly, partly because of problems in the transmission process (as explained above). However, our guess is that credit growth may recover to some extent going forward as policy eases further to drive credit (to targeted sectors) and the quasi-fiscal sector.

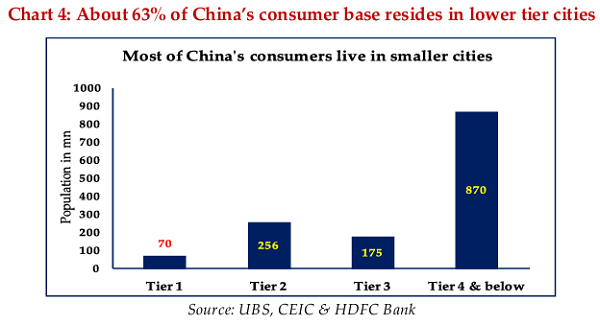

3. Healthy consumption story: One of the biggest supports to the economy, in our opinion, comes from a booming retail sector in China especially in tier 3 &4 cities. As per estimates, consumption in China’s smaller cities could triple by 2030, owing to favorable government policies, a population boom and higher disposable household income. Consumption in lower-tier cities is likely to surge (mainly led by e-commerce) from U.S.$2.3 trillion in 2017 to U.S.$6.9 trillion in 2030, as per Morgan Stanley estimates. This, we believe, is an underestimated prowess that the Chinese economy has.

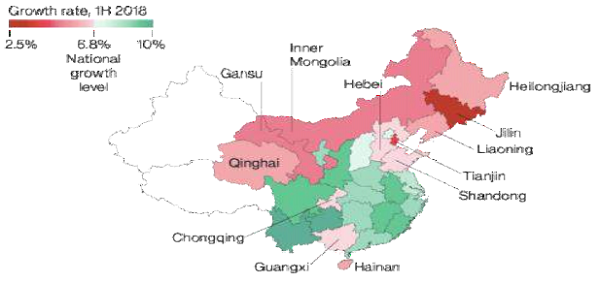

4. Regional Growth divergence: Beneath a very steady growth rate of 6.7 – 6.9% growth rate for the whole economy, there lies a stark divergence among China’s 31 regions — from a modest 2.5% expansion to a 10% boom. For instance, the economy of Guizhou, a less-developed southwestern province which recently made a major bet on the big data industry, is at the top with a 10% percent growth pace, while northeastern Jilin, which borders North Korea, expanded at the slowest pace of 2.5%.3

4. Regional Growth divergence: Beneath a very steady growth rate of 6.7 – 6.9% growth rate for the whole economy, there lies a stark divergence among China’s 31 regions — from a modest 2.5% expansion to a 10% boom. For instance, the economy of Guizhou, a less-developed southwestern province which recently made a major bet on the big data industry, is at the top with a 10% percent growth pace, while northeastern Jilin, which borders North Korea, expanded at the slowest pace of 2.5%.3

What is encouraging here is that companies are keeping this divergence in mind while making their investment and business decisions. For instance, fixed-asset investment, jumped 17.4% in Guizhou while slumping 19.5% in Shanxi, whose coal-focused economy has struggled for years. Factory momentum also varied. Manufacturers in Yunnan (grew 9.2% in H1 2018) boosted their output more than 10%, side-lining the 1.8% percent increase in Chongqing. These nuances about the economy, while often gets side-lined in a broader macro analysis, bode well for the growth going ahead.

What is encouraging here is that companies are keeping this divergence in mind while making their investment and business decisions. For instance, fixed-asset investment, jumped 17.4% in Guizhou while slumping 19.5% in Shanxi, whose coal-focused economy has struggled for years. Factory momentum also varied. Manufacturers in Yunnan (grew 9.2% in H1 2018) boosted their output more than 10%, side-lining the 1.8% percent increase in Chongqing. These nuances about the economy, while often gets side-lined in a broader macro analysis, bode well for the growth going ahead.

Disclaimer: This document has been prepared for your information only and does not constitute any offer/commitment to transact. Such an offer would be subject to contractual confirmations, satisfactory documentation and prevailing market conditions. Reasonable care has been taken to prepare this document. HDFC Bank and its employees do not accept any responsibility for action taken on the basis of this document

Notes:-

1 Important to note that though the volume China buys from the U.S. has risen some 200-fold in the past two years, American crude still accounts for only 3% of Chinese imports. China’s biggest suppliers are Russia and Saudi Arabia.

2 Source: PIMCO

3 Source: Bloomberg

*Mr. Abheek Barua, Chief Economist, HDFC Bank. Mr. Barua tweets at @AbheekHDFCBank.