Case Law Details

DCIT (E) Vs Rashtrotthana Parishat Keshava Shilpa (ITAT Bangalore)

ITAT Bangalore held that that mens rea is not an essential condition for imposing penalties under civil acts. Penalty u/s. 270A of the Income Tax Act nowhere specifically refers necessity of presence of mens rea for levy of penalty. Accordingly, appeal of revenue allowed.

Facts- Assessee is a trust. During assessment proceedings, AO held that revenue expenditure claimed as application of income includes the depreciation claim and the depreciation claim is in contravention of section 11(6) of the Act as the assessee has also claimed the capital expenditure as application of income which according to AO amounts to claim of double deduction and accordingly disallowed the claim of depreciation amounting to Rs.7,53,66,656/- claimed by the assessee trust as it violates section 11(6) of the Act.

Further, with regard to claim of Loss on sale of vehicle amounting to Rs.1,77,853/- as application of Income, the AO disallowed the same & not treated as application of Income on the ground that the assessee trust has not expended any amounts towards the items of expenditure & further the entire cost of acquisition of vehicle was allowed as application in earlier years & thus held that the loss cannot be treated as application again.

Finally, on or before completing the assessment proceedings, the AO initiated the penalty proceedings u/s 270A of the Act in respect of disallowance of depreciation claimed as application amounting to Rs.7,53,66,656/-. AO in the said penalty notice had also observe that in the course of proceedings before me for the Assessment year 2017-18, it appears to me Under-reporting /misreporting of income. AO held that the assessee has misreported its income for the Asst. year 2017-18 and as per section 270A of the Act, the quantum of misreported income is Rs.7,53,66,656/-. As per sub-section (8) of section 270A of the Act, the penalty on misreported income shall be a sum equal to two hundred percent of the amount of tax payable on misreported income and accordingly the AO levied penalty of Rs. 5,31,48,508/- U/s 270A of the Act.

CIT(A) deleted the penalty. Being aggrieved, revenue has preferred the present appeal.

Conclusion- It is well settled law that mens rea is not an essential condition for imposing penalties under civil acts. This is because the intention of the legislation is clear, and the penalty is levied once a specific eventuality occurs as prescribed under section 270A of the Act. The Apex Court has also ruled that penalty provisions are for breach of civil obligation, so mens rea is not an essential ingredient. Further the Mens rea is not necessary for a conviction in strict liability crimes. This means that someone can be held accountable for the deed itself, regardless of whether they intended to commit the crime.

Held that the assessee had option to rectify its mistake by filing revised return of income as per section 139(5) of the Act and during the proceedings it was noticed by AO that assessee has not filed it voluntarily. More remarkably during the course of Assessment proceedings, as observed by the AO, the assessee submitted that depreciation on assets has not been claimed as application of Income. Considering that no cross objection (CO) being filed by the assessee & also considering the totality of the facts of the case & by relying upon the judgment of the Apex Court, we set aside the Order of the ld. CIT(A)/NFAC & sustain the order of the AO in levying the Penalty U/s 270A of the Act by allowing the appeal filed by the Revenue.

FULL TEXT OF THE ORDER OF ITAT BANGALORE

This appeal at the instance of the Revenue is directed against the CIT(A)/NFAC’s order dated 04.07.2024 vide DIN & order No. ITBA/NFAC/S/250/2024-25/1066399025(1) passed under Section 250 of the Income Tax Act, 1961 (in short “the Act”) for the Assessment Year (AY) 2017-18.

The assessee has not filed any cross objections (CO) against this appeal filed by the Revenue.

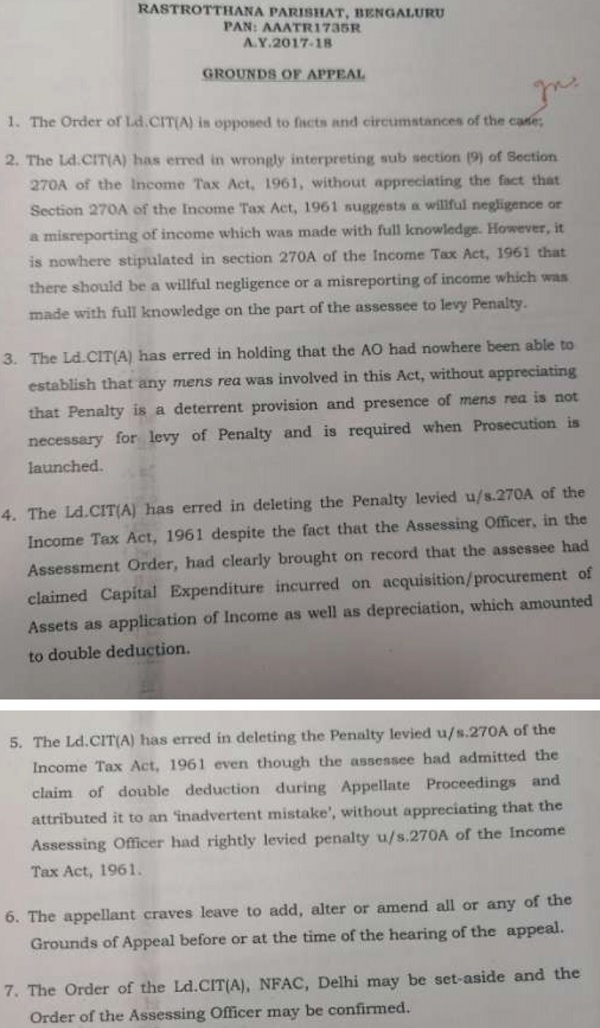

2. The Revenue has raised the following grounds of appeal: –

3. Before leaping straightway to the penalty proceedings, it is very much pertinent here to discuss with regard to the disallowances made in the assessment proceedings for ease of understanding and appreciating the real facts which leads to the initiation of penalty proceedings.

3.1 Brief facts of the case are that the assessee Trust filed its return of Income for the Asst. year 2017-18 on 28/10/2017 declaring Nil Income after claiming exemption u/s 11 of the Act. Thereafter the case was selected for scrutiny under CASS. During the course of the Assessment proceedings the AO asked to furnish details of depreciation claimed (Block-wise), details of Asset acquired and details of application during the F.Y 2016-17, previous years with respect to acquisition/procurement of capital asset(s) against which depreciation has been claimed for A.Y 201718 and to substantiate their claim of depreciation and amount incurred for capital assets claimed as application vis-à-vis section 11(6) of the Act.

3.2 As observed by the AO, in response the assessee has submitted replies on various dates furnishing therein partial details called for and more notably also submitted that depreciation on assets has not been claimed as application of Income.

3.3 The AO on verification of return filed and the submissions made, noticed that the revenue expenditure claimed as application of income is Rs.55,56,54,057/- which is inclusive of depreciation claim of Rs. 7,53,66,656/-. Further the auditor in his Audit report furnished in form 10B has declared the amount of income applied to charitable or religious purposes in India during the Asst. year 2017-18 as Rs. 67,70,38,920/- [ Rs.55,56,54,057/- (revenue expenditure) + Rs. 8,11,20,826/- (capital expenditure) ].

3.4 The AO on verification of details furnished noticed that the depreciation claim is also made in the computation of Income and Income & expenditure submitted by the assessee. Accordingly the AO held that revenue expenditure claimed as application of income includes the depreciation claim and the depreciation claim is in contravention of section 11(6) of the Act as the assessee has also claimed the capital expenditure as application of income which according to AO amounts to claim of double deduction and accordingly disallowed the claim of depreciation amounting to Rs.7,53,66,656/- claimed by the assessee trust as it violates section 11(6) of the Act.

3.5 Further, with regard to claim of Loss on sale of vehicle amounting to Rs.1,77,853/- as application of Income, the AO disallowed the same & not treated as application of Income on the ground that the assessee trust has not expended any amounts towards the items of expenditure & further the entire cost of acquisition of vehicle was allowed as application in earlier years & thus held that the loss cannot be treated as application again.

3.6 Finally, on or before completing the assessment proceedings, the AO initiated the penalty proceedings u/s 270A of the Act in respect of disallowance of depreciation claimed as application amounting to Rs.7,53,66,656/- by stipulating the following reasons in the order of assessment-

“11. The nature of additions made as detailed in the foregoing paragraphs attracts the provisions of section 270A of the Income –tax Act,1961 in as much as the assessee has mis-reported the income in the Return of Income filed by the assessee on 28-10-2017 for the assessment year 2017-18. The assessee has claimed both the capital expenses and depreciation as application of income. Therefore, penalty proceedings are initiated u/s.274 read with section 270A of the Income-tax Act, 1961 separately.”

Penalty Notice u/s 274 r.w.s. 270A of Income Tax Act, 1961 for misreporting of income is enclosed herewith.

3.7 Thereafter, the AO issued penalty notice u/s 274 r.w.s. 270A of the Act dated 23/12/2019 requesting the assessee trust to appear and show cause as to why an order imposing a penalty u/s 270A of the Act should not be made under section 270A of the Act. The AO in the said penalty notice had also observe that in the course of proceedings before me for the Assessment year 2017-18, it appears to me Under-reporting /misreporting of income.

3.8 During the course of the Penalty proceedings, the assessee submitted that there has been neither an under reporting/misreporting of income. Further the assessee admitted that by oversight while computing the income, the assessee trust omitted to add back depreciation which is purely a clerical error and not deliberate. Further the assessee trust also submitted that the their case is also not covered by any of the provision listed in sub section (2) of section 270A which defines under reporting and accordingly prayed to condone the bonafide error on their part & drop the penalty proceedings initiated under section 270A of the Act.

3.9 The AO after considering the above reply of the assessee trust held that the assessee contention is not found to be acceptable. The AO was of the opinion that the assessee had option to rectify its mistake by filing revised return of income as per section 139(5) of the Act and during the proceedings, it was noticed by AO that the assessee has not filed it voluntarily. In view of the above facts, the AO held that the assessee has misreported its income for the Asst. year 2017-18 and as per section 270A of the Act, the quantum of misreported income is Rs.7,53,66,656/-. As per sub-section (8) of section 270A of the Act, the penalty on misreported income shall be a sum equal to two hundred percent of the amount of tax payable on misreported income and accordingly the AO levied penalty of Rs. 5,31,48,508/- U/s 270A of the Act.

4. Aggrieved by the penalty order passed u/s 270A of the Act dated 26.2.2022, the assessee had preferred an appeal before the ld. CIT(A)/NFAC.

5. The Ld. CIT(A)/NFAC however allowed the appeal of the assessee by deleting the penalty levied u/s 270A of the Act amounting to Rs.5,31,48,508/- mainly on the following grounds /observations:-

5.1 The Sub section (9) of section 270A details the specific acts of omission or commission that would amount to misrepresentation of facts. The above suggests a willful negligence or a misreporting of income which was made with full knowledge. Hence the assessee should have misreported with full intention of evading taxes and mens rea should be present.

5.2 The AO has not been able to prove that the assessee had engaged in willful misreporting.

5.3 The AO has not anywhere been able to establish that any mens rea was involved in this act, and that the assessee willfully misrepresented or suppressed the facts. The AO has only been able to establish the violation of the provision of sub section (6).

5.4 The very fact that this was the only year where such wrong claim was made points towards inadvertency of the Act. Further even without the drawl of claim of depreciation there is no positive income.

5.5 Lastly the ld. CIT(A)/NFAC, held that the claim of depreciation made by the assessee in his return was inadvertent and a bonafide mistake and accordingly deleted the penalty u/s 270A of the Act.

6. Aggrieved by the order of the ld. CIT(A)/NFAC dated 04.07.2024, the Revenue has filed the present appeal before this Tribunal. The assessee has filed the paper book comprising 80 pages containing various documents filed/produced before the Authorities below.

7. Before us, the ld. CIT-D.R. Ms. Neera Malhotra fervently submitted that the ld. CIT(A)/NFAC wrongly interpreted sub section (9) of section 270A of the Act in holding that 270A(9) of the Act suggests a willful negligence or a misreporting of income which was made with full knowledge however it is no where stipulated in section 270A. Further the ld. CIT-D.R submitted in view of the judgment of the Apex Court, it is settled position that the presence of mens rea is not at all necessary for levy of Penalty and is required only when prosecution is launched. Lastly she argued that ld. CIT(A)/NFAC erred in deleting the penalty even though the assessee had admitted the claim of double deduction before the Appellate Proceedings.

8. The ld. AR of the assessee on the other hand supported the order of the ld. CIT(A)/NFAC and reiterated the same grounds as placed before the lower authorities and submitted that by oversight while computing the income, the assessee trust omitted to add back the depreciation which is purely a clerical error and not deliberate. Further AR of the assessee heavily relied upon the judgment of the Apex Court in the case of Price Waterhouse Coopers (P.) Ltd. v. Commissioner of Income Tax, Kolkata-I reported in [2012] 25 taxmann.com 400 (SC). Further AR of the assessee submitted that even penalty notice dated 23/12/2019 does not specify under which limb the revenue is proposed to levy penalty by not striking off the irrelevant portion.

9. We have heard the rival submissions and perused the materials available on record. The AO has passed an order u/s 143(3) of the Act on 23.12.2019 by making two disallowances in the assessment order viz. (a) Disallowance of Depreciation amounting to Rs. 7,53,66,656/- and (b) disallowance of loss on sale of vehicles amounting to Rs.1,77,853/-. The AO initiated the penalty proceedings U/s 274 read with 270A of the Act with regard to disallowances made towards the claim of depreciation on the ground that the revenue expenditure claimed as application of income includes the depreciation claim and the depreciation claim is in contravention of section 11(6) of the Act as the assessee has also claimed the capital expenditure as application of income which according to AO amounts to claim of double deduction. During the course of penalty proceedings the assessee submitted that by oversight while computing the income, the assessee trust omitted to add back depreciation which is purely a clerical error and not deliberate.

9.1 It is an undisputed fact that the assessee trust had not corrected the said mistake by filing the revised return as per the provisions contained u/s 139(5) of the Act as correctly observed by the AO in his penalty Order. It is only during the course of the assessment proceeding, the AO on verification of return filed and the submissions made, noticed that the revenue expenditure claimed as application of income includes the depreciation claim and the depreciation claim is in contravention of section 11(6) of the Act as the assessee has also claimed the capital expenditure as application of income which according to AO amounts to claim of double deduction. We take a note of the fact that even during the course of the Asst. proceedings, as observed by the AO that the assessee has submitted replies on various dates furnishing therein partial details called for and more notably also submitted that depreciation on assets has not been claimed as application of Income. Therefore we are of the opinion that from the conduct, behavior and attitude of the assessee, it is clear that the assessee was fully aware of the fact of claiming double deduction i.e one as an application for capital expenditure incurred and secondly the depreciation on such capital expenditure as application in contravention of section 11(6) of the Act.

9.2 Further, the assessee’s claim that by oversight while computing the income, the assessee trust omitted to add back depreciation is also not tenable being afterthought as the auditor in his Audit report furnished in form 10B has declared the amount of income applied to charitable or religious purposes in India during the Asst. year 2017-18 as Rs. 67,70,38,920/- [ Rs.55,56,54,057/-(revenue expenditure) + Rs. 8,11,20,826/- (capital expenditure)] which amounts to claim of double deduction & the same is accepted by the assessee on the I. Tax web portal. It is worthwhile here to note that once the Auditor uploads the audit report on the I. Tax Web Portal from his professional ID, it automatically goes to the ID of the assessee for the approval. Upon receipt of the audit report, the assessee either can approve the audit report or disapprove the same by stating the reasons for the disapproval. Once it is approved by the assessee by putting his digital signature, the process of filing the audit report then only gets completed. On going through the paper book submitted by the assessee, the Audit Report for the Asst. year 2017-18 was uploaded way back on 20/06/2017 whereas the statement of Income is prepared on dated 28/10/2017 & on the same date the return is also filed. Further we are of the opinion that everything would depend upon the Return of Income filed because that is the only document where the assessee trust can under report its Income or mis-report its Income. When such Income are found to be under reported in the return of Income or misreported in the return, then only the liability would arise. Therefore the contention of the assessee that while computing the income, the assessee trust by sight omitted to add back depreciation cannot be accepted at all.

9.3 On going through the rationale in allowing the appeal of the assessee, we find that the ld.CIT(A)/NFAC is of the view that section 270A(9) of the Act suggest a willful negligence or a misreporting of income which is made with full knowledge. Thus the main contention of the ld. CIT(A)/NFAC is that the assessee should have misreported with full intention of evading taxes & mens-rea should be present in order to levy penalty U/s 270A of the Act. In the opinion of ld. CIT(A)/NFAC the AO has failed to establish that any mens rea was involved & the assessee willfully misrepresented or suppressed the facts.

9.4 For the purpose of evaluating the correctness of rival submissions addressed we deem it apposite to extract section 270A of the Act herein below:

270A. Penalty for under-reporting and misreporting of income.

(1)The Assessing Officer or the Commissioner (Appeals) or the Principal Commissioner or Commissioner may, during the course of any proceedings under this Act, direct that any person who has under-reported his income shall be liable to pay a penalty in addition to tax, if any, on the under-reported income.

(2)A person shall be considered to have under-reported his income, if—

(a)the income assessed is greater than the income determined in the return processed under clause (a) of sub-section (1) of section 143;

(b)the income assessed is greater than the maximum amount not chargeable to tax, where no return of income has been furnished or where return has been furnished for the first time under section 148;

(c)the income reassessed is greater than the income assessed or reassessed immediately before such reassessment;

(d)the amount of deemed total income assessed or reassessed as per the provisions of section 115JB or section 115JC, as the case may be, is greater than the deemed total income determined in the return processed under clause (a) of sub-section (1) of section 143;

(e)the amount of deemed total income assessed as per the provisions of section 115JB or section 115JC is greater than the maximum amount not chargeable to tax, where no return of income has been furnished or where return has been furnished for the first time under section 148;

(f)the amount of deemed total income reassessed as per the provisions of section 115JB or section 115JC, as the case may be, is greater than the deemed total income assessed or reassessed immediately before such reassessment;

(g)the income assessed or reassessed has the effect of reducing the loss or converting such loss into income.

(3)The amount of under-reported income shall be,—

(i)in a case where income has been assessed for the first time,—

(a)if return has been furnished, the difference between the amount of income assessed and the amount of income determined under clause (a) of sub-section (1) of section 143;

(b)in a case where no return of income has been furnished or where return has been furnished for the first time under section 148,—

(A)the amount of income assessed, in the case of a company, firm or local authority; and

(B)the difference between the amount of income assessed and the maximum amount not chargeable to tax, in a case not covered in item (A);

(ii)in any other case, the difference between the amount of income reassessed or recomputed and the amount of income assessed, reassessed or recomputed in a preceding order:

Provided that where under-reported income arises out of determination of deemed total income in accordance with the provisions of section 115JB or section 115JC, the amount of total under-reported income shall be determined in accordance with the following formula—

(A — B) + (C — D)

where,

A = the total income assessed as per the provisions other than the provisions contained in section 115JB or section 115JC (herein called general provisions);

B = the total income that would have been chargeable had the total income assessed as per the general provisions been reduced by the amount of underreported income;

C = the total income assessed as per the provisions contained in section 115JB or section 115JC;

D = the total income that would have been chargeable had the total income assessed as per the provisions contained in section 115JB or section 115JC been reduced by the amount of under-reported income:

Provided further that where the amount of under-reported income on any issue is considered both under the provisions contained in section 115JB or section 115JC and under general provisions, such amount shall not be reduced from total income assessed while determining the amount under item D.

Explanation.—For the purposes of this section,—

(a)”preceding order” means an order immediately preceding the order during the course of which the penalty under sub-section (1) has been initiated;

(b)in a case where an assessment or reassessment has the effect of reducing the loss declared in the return or converting that loss into income, the amount of under-reported income shall be the difference between the loss claimed and the income or loss, as the case may be, assessed or reassessed.

(4)Subject to the provisions of sub-section (6), where the source of any receipt, deposit or investment in any assessment year is claimed to be an amount added to income or deducted while computing loss, as the case may be, in the assessment of such person in any year prior to the assessment year in which such receipt, deposit or investment appears (hereinafter referred to as “preceding year”) and no penalty was levied for such preceding year, then, the under-reported income shall include such amount as is sufficient to cover such receipt, deposit or investment.

(5)The amount referred to in sub-section (4) shall be deemed to be amount of income under-reported for the preceding year in the following order—

(a)the preceding year immediately before the year in which the receipt, deposit or investment appears, being the first preceding year; and

(b) where the amount added or deducted in the first preceding year is not sufficient to cover the receipt, deposit or investment, the year immediately preceding the first preceding year and so on.

(6)The under-reported income, for the purposes of this section, shall not include the following, namely:—

(a) the amount of income in respect of which the assessee offers an explanation and the Assessing Officer or the Commissioner (Appeals) or the Commissioner or the Principal Commissioner, as the case may be, is satisfied that the explanation is bona fide and the assessee has disclosed all the material facts to substantiate the explanation offered;

(b) the amount of under-reported income determined on the basis of an estimate, if the accounts are correct and complete to the satisfaction of the Assessing Officer or the Commissioner (Appeals) or the Commissioner or the Principal Commissioner, as the case may be, but the method employed is such that the income cannot properly be deduced therefrom;

(c) the amount of under-reported income determined on the basis of an estimate, if the assessee has, on his own, estimated a lower amount of addition or disallowance on the same issue, has included such amount in the computation of his income and has disclosed all the facts material to the addition or disallowance;

(d) the amount of under-reported income represented by any addition made in conformity with the arm’s length price determined by the Transfer Pricing Officer, where the assessee had maintained information and documents as prescribed under section 92D, declared the international transaction under Chapter X, and, disclosed all the material facts relating to the transaction; and

(e) the amount of undisclosed income referred to in section 271AAB.

(7) The penalty referred to in sub-section (1) shall be a sum equal to fifty per cent of the amount of tax payable on under-reported income.

(8) Notwithstanding anything contained in sub-section (6) or sub-section (7), where under-reported income is in consequence of any misreporting thereof by any person, the penalty referred to in sub-section (1) shall be equal to two hundred per cent of the amount of tax payable on under-reported income.

(9) The cases of misreporting of income referred to in sub-section (8) shall be the following, namely:—

(a) misrepresentation or suppression of facts;

(b) failure to record investments in the books of account;

(c) claim of expenditure not substantiated by any evidence;

(d) recording of any false entry in the books of account;

(e) failure to record any receipt in books of account having a bearing on total income; and

(f) failure to report any international transaction or any transaction deemed to be an international transaction or any specified domestic transaction, to which the provisions of Chapter X apply.

(10)The tax payable in respect of the under-reported income shall be—

(a) where no return of income has been furnished or where return has been furnished for the first time under section 148 and the income has been assessed for the first time, the amount of tax calculated on the under-reported income as increased by the maximum amount not chargeable to tax as if it were the total income;

(b) where the total income determined under clause (a) of sub-section (1) of section 143 or assessed, reassessed or recomputed in a preceding order is a loss, the amount of tax calculated on the under-reported income as if it were the total income;

(c) in any other case, determined in accordance with the formula—(XY) where,

X = the amount of tax calculated on the under-reported income as increased by the total income determined under clause (a) of sub-section (1) of section 143 or total income assessed, reassessed or recomputed in a preceding order as if it were the total income; and

Y = the amount of tax calculated on the total income determined under clause (a) of sub-section (1) of section 143 or total income assessed, reassessed or recomputed in a preceding order.

(11) No addition or disallowance of an amount shall form the basis for imposition of penalty, if such addition or disallowance has formed the basis of imposition of penalty in the case of the person for the same or any other assessment year.

(12) The penalty referred to in sub-section (1) shall be imposed, by an order in writing, by the Assessing Officer, the Commissioner (Appeals), the Commissioner or the Principal Commissioner, as the case may be.

9.5 On going through the above, we find no reference of any mens rea in section 270A of the Act & therefore we find force in the contention of the ld. CIT-DR that the ld. CIT(A)/NFAC has erred in interpreting sub section (9) of section 270A of the Act by stating that 270A(9) suggests a willful negligence or a misreporting of income which made with full knowledge. Further on going through the Section we also agree with the ld. DR that nowhere in the section 270A of the Act specifically refers necessity of the presence of mens rea for levy of penalty.

9.6 It is well settled law that mens rea is not an essential condition for imposing penalties under civil acts. This is because the intention of the legislation is clear, and the penalty is levied once a specific eventuality occurs as prescribed under section 270A of the Act. The Apex Court has also ruled that penalty provisions are for breach of civil obligation, so mens rea is not an essential ingredient. Further the Mens rea is not necessary for a conviction in strict liability crimes. This means that someone can be held accountable for the deed itself, regardless of whether they intended to commit the crime. We relying on the judgment of the Supreme Court in the case of Union of India v. Dharamendra Textile Processors reported in (2008) 306 ITR 277 (SC). The relevant observations are reproduced below for ease of reference-

“33. This Court in a catena of decisions has held that mens rea is not an essential element for imposing penalty for breach of civil obligations :

(a) Director of Enforcement v. MCTM Corpn. (P.) Ltd. [1996] 2 SCC 471 (SCC pp. 478 & 480-81, paras 8 & 12-13)

“8. It is thus the breach of a ‘civil obligation’ which attracts ‘penalty’ under section 23(1)(a), FERA, 1947 and a finding that the delinquent has contravened the provisions of section 10, FERA, 1947 that would immediately attract the levy of ‘penalty’ under section 23, irrespective of the fact whether the contravention was made by the defaulter with any ‘guilty intention’ or not. Therefore, unlike in a criminal case, where it is essential for the ‘prosecution’ to establish that the ‘accused’ had the necessary guilty intention or in other words the requisite ‘mens rea’ to commit the alleged offence with which he is charged before recording his conviction, the obligation on the part of the Directorate of Enforcement, in cases of contravention of the provisions of section 10 of FERA, would be discharged where it is shown that the ‘blameworthy conduct’ of the delinquent had been established by wilful contravention by him of the provisions of section 10, FERA, 1947. It is thedelinquency of the defaulter itself which establishes his ‘blameworthy’ conduct, attracting the provisions of section 23(1)(a) of FERA, 1947 without any further proof of the existence of ‘mens rea’. Even after an adjudication by the authorities and levy of penalty under section 23(1)(a) of FERA, 1947, the defaulter can still be tried and punished for the commission of an offence under the penal law . . .

******

12. In Corpus Juris Secundum, Vol. 85, at p. 580, para 1023, it is stated thus:

‘A penalty imposed for a tax delinquency is a civil obligation, remedial and coercive in its nature, and is far different from the penalty for a crime or a fine or forfeiture provided as punishment for the violation of criminal or penal laws.’

13. We are in agreement with the aforesaid view and in our opinion, what applies to ‘tax delinquency’ equally holds good for the ‘blameworthy’ conduct for contravention of the provisions of FERA, 1947. We, therefore, hold that mens rea (as is understood in criminal law) is not an essential ingredient for holding a delinquent liable to pay penalty under section 23(1)(a) of FERA, 1947 for contravention of the provisions of section 10 of FERA, 1947 and that penalty is attracted under section 23(1)(a) as soon as contravention of the statutory obligation contemplated by section 10(1)(a) is established. The High Court apparently fell in error in treating the ‘blameworthy conduct’ under the Act as equivalent to the commission of a ‘criminal offence’, overlooking the position that the ‘blameworthy conduct’ in the adjudicatory proceedings is established by proof only of the breach of a civil obligation under the Act, for which the defaulter is obliged to make amends by payment of the penalty imposed under section 23(1)(a) of the Act irrespective of the fact whether he committed the breach with or without any guilty intention.”

(b) J.K. Industries Ltd. v. Chief Inspector of Factories & Boilers [1996] 6 SCC 665 (SCC p. 692, para 42)

“42. The offences under the Act are not a part of general penal law but arise from the breach of a duty provided in a special beneficial social defence legislation, which creates absolute or strict liability without proof of any mens rea. The offences are strict statutory offences for which establishment of mens rea is not an essential ingredient. The omission or commission of the statutory breach is itself the offence. Similar type of offences based on the principle of strict liability, which means liability without fault or mens rea, exist in many statutes relating to economic crimes as well as in laws concerning the industry, food adulteration, prevention of pollution, etc. in India and abroad. ‘Absolute offences’ are not criminal offences in any real sense but acts which are prohibited in the interest of welfare of the public and the prohibition is backed by sanction of penalty.”

(c) R. S. Joshi v. Ajit Mills Ltd. [1977] 4 SCC 98 (SCC p. 110, para 19)

“Even here we may reject the notion that a penalty or a punishment cannot be cast in the form of an absolute or no-fault liability but must be preceded by mens rea. The classical view that ‘no mens rea, no crime’ has long ago been eroded and several laws in India and abroad, especially regarding economic crimes and departmental penalties, have created severe punishments even where the offences have been defined to exclude mens rea. Therefore, the contention that section 37(1) fastens a heavy liability regardless of fault has no force in depriving the forfeiture of the character of penalty.”

(d) Gujarat Travancore Agency v. CIT [1989] 3 SCC 52 SCC (p. 55, para 4).

“It is sufficient for us to refer to section 271(1)(a), which provides that a penalty may be imposed if the Income-tax Officer is satisfied that any person has without reasonable cause failed to furnish the return of total income, and to section 276C which provides that if a person wilfully fails to furnish in due time the return of income required under section 139(1), he shall be punishable with rigorous imprisonment for a term which may extend to one year or with fine. It is clear that in the former case what is intended is a civil obligation while in the latter what is imposed is a criminal sentence. There can be no dispute that having regard to the provisions of section 276C, which speaks of wilful failure on the part of the defaulter and taking into consideration the nature of the penalty, which is punitive, no sentence can be imposed under that provision unless the element of mens rea is established. In most cases of criminal liability, the intention of the Legislature is that the penalty should serve as a deterrent. The creation of an offence by statute proceeds on the assumption that society suffers injury by the act or omission of the defaulter and that a deterrent must be imposed to discourage the repetition of the offence. In the case of a proceeding under section 271(1)(a), however, it seems that the intention of the Legislature is to emphasise the fact of loss of revenue and to provide a remedy for such loss, although no doubt an element of coercion is present in the penalty. In this connection the terms in which the penalty falls to be measured is significant. Unless there is something in the language of the statute indicating the need to establish the element of mens rea it is generally sufficient to prove that a default in complying with the statute has occurred. In our opinion, there is nothing in section 271(1)(a) which requires that mens rea must be proved before penalty can be levied under that provision.

(e) Swedish Match AB v. SEBI [2004] 11 SCC 641 (SCC p. 671, para 113)

“The provisions of section 15H of the Act mandate that a penalty of rupees twenty-five crores may be imposed. The Board does not have any discretion in the matter and, thus, the adjudication proceeding is a mere formality. Imposition of penalty upon the appellant would, thus, be a forgone conclusion. Only in the criminal proceedings initiated against the appellants, existence of mens rea on the part of the appellants will come up for consideration.”

(f) SEBI v. Cabot International Capital Corpn. [2005] 123 Comp. Cas. 841 (Bom.) (Comp. Cas. pp. 862 & 864-65, paras 47, 52 and 54)

“47. Thus, the following extracted principles are summarised :

(A) Mens rea is an essential or sine qua non for criminal offence.

(B) A straitjacket formula of mens rea cannot be blindly followed in each and every case. The scheme of a particular statute may be diluted in a given case.

(C) If, from the scheme, object and words used in the statute, it appears that the proceedings for imposition of the penalty are adjudicatory in nature, in contradistinction to criminal or quasi-criminal proceedings, the determination is of the breach of the civil obligation by the offender. The word ‘penalty’ by itself will not be determinative to conclude the nature of proceedings being criminal or quasi-criminal. The relevant considerations being the nature of the functions being discharged by the authority and the determination of the liability of the contravenor and the delinquency.

(D) Mens rea is not essential element for imposing penalty for breach of civil obligations or liabilities.

There can be two distinct liabilities, civil and criminal under the same Act.

******

52. The SEBI Act and the Regulations, are intended to regulate the securities market and the related aspects, the imposition of penalty, in the given facts and circumstances of the case, cannot be tested on the ground of ‘no mens rea, no penalty’. For breaches of provisions of the SEBI Act and Regulations, according to us, which are civil in nature, mens rea is not essential. On particular facts and circumstances of the case, proper exercise of judicial discretion is a must, but not on foundation that mens rea is essential to impose penalty in each and every breach of provisions of the SEBI Act.

53.******

54. However, we are not in agreement with the Appellate Authority in respect of the reasoning given in regard to the necessity of mens rea being essential for imposing the penalty. According to us, mens rea is not essential for imposing civil penalties under the SEBI Act and Regulations.” [Emphasis supplied] (pp. 366, 369, 372)

11. The decision in Bharat Heavy Electrical’s case (supra) cannot be of any assistance to the assessee because the same proceeded on the basis of concession. Even otherwise, it was not open to the Bench to read, into a statute which was specific and clear, something which is not specifically provided for in the statute.

12. The stand of learned counsel for the assessee is that the absence of specific reference to mens rea is a case of casus omissus. If the contention of learned counsel for the assessee is accepted that the use of the expression “assessee shall be liable” proves the existence of discretion, it would lead to a very absurd result. In fact in the same provision there is an expression used i.e., “liability to pay duty”. It can by no stretch of imagination be said that the adjudicating authority has even a discretion to levy duty less than what is legally and statutorily leviable. Most of cases relied upon by learned counsel for the assessee had their foundation on Bharat Heavy Electrical’s case (supra). As noted above, the same is based on concession and in any event did not indicate the correct position in law.

13. It is a well-settled principle in law that the court cannot read anything into a statutory provision or a stipulated condition which is plain and unambiguous. A statute is an edict of the Legislature. The language employed in a statute is the determinative factor of legislative intent. Similar is the position for conditions stipulated in advertisements.

14. Words and phrases are symbols that stimulate mental references to referents. The object of interpreting a statute is to ascertain the intention of the Legislature enacting it. (See Institute of Chartered Accountants of India v. Price Waterhouse [1997] 6 SCC 312). The intention of the Legislature is primarily to be gathered from the language used, which means that attention should be paid to what has been said as also to what has not been said. As a consequence, a construction which requires for its support, addition or substitution of words or which results in rejection of words as meaningless has to be avoided. As observed in Crawford v. Spooner [1846] 6 MOO PC1, the courts cannot aid the Legislature’s defective phrasing of an Act, they cannot add or mend, and by construction make up deficiencies which are left there.—See State of Gujarat v. Dilipbhai Nathjibhai Patel [1998] 3 SCC 234. It is contrary to all rules of construction to read words into an Act unless it is absolutely necessary to do so. [See Stock v. Frank Jones (Tipton) Ltd. 1978 (1) ALL ER 948]. Rules of interpretation do not permit the courts to do so, unless the provision as it stands is meaningless or of doubtful meaning. The courts are not entitled to read words into an Act of Parliament unless clear reason for it is to be found within the four corners of the Act itself. (Per Lord Loreburn, L.C. in Vickers Sons)

15. The question is not what may be supposed and has been intended but what has been said. ‘Statutes should be construed not as theorems of Euclid’, Judge Learned Hand said, ‘but words must be construed with some imagination of the purposes which lie behind them’. (See Lenigh Valley Coal Co. v. Yensavage 218 FR 547). The view was reiterated in Union of India v. Filip Tiago De Gama of Vedem Vasco De Gama [1990] 1 SCC 277 (SCC p. 284, para 16).

16. In D.R. Venkatachalam v. Dy. Transport Commr. [1977] 2 SCC 273, it was observed that the courts must avoid the danger of a prior determination of the meaning of a provision based on their own preconceived notions of ideological structure or scheme into which the provision to be interpreted is somewhat fitted. They are not entitled to usurp legislative function under the disguise of interpretation.

17. While interpreting a provision the court only interprets the law and cannot legislate it. If a provision of law is misused and subjected to the abuse of process of law, it is for the Legislature to amend, modify or repeal it, if deemed necessary. See CST v. Popular Trading Co. [2000] 5 SCC 511. The legislative casus omissuscannot be supplied by judicial interpretative process.

18. Two principles of construction – one relating to casus omissus and the other in regard to reading the statute as a whole, appear to be well-settled. Under the first principle a casus omissus cannot be supplied by the court except in the case of clear necessity and when reason for it is found in the four corners of the statute itself but at the same time a casus omissus should not be readily inferred and for that purpose all the parts of a statute or section must be construed together and every clause of a section should be construed with reference to the context and other clauses thereof so that the construction to be put on a particular provision makes a consistent enactment of the whole statute. This would be more so if literal construction of a particular clause leads to manifestly absurd or anomalous results which could not have been intended by the Legislature. “An intention to produce an unreasonable result”, said Danckwerts, LJ. in Artemiou v. Procopiou [1965] 3 ALL ER 539 (All ER p. 544 I) “is not to be imputed to a statute if there is some other construction available”. Where to apply words literally would “defeat the obvious intention of the legislation and produce a wholly unreasonable result”, we must “do some violence to the words” and so achieve that obvious intention and produce a rational construction. [Per Lord Reid in Luke v. IRC [1963] AC 557 where at AC p. 577 he also observed : (All ER p. 664 I). “This is not a new problem, though our standard of drafting is such.

19. It is then true that :

“When the words of a law extend not to an inconvenience seldom happening, but due to those which often happen, it is good reason not to strain the words further than they reach, by saying it is casus omissus, and that the law intended quaefre quentius accidunt .”

“But”, on the other hand,

“it is no reason, when the words of a law do enough extend to an inconvenience seldom happening, that they should not extend to it as well as if it happened more frequently, because it happens but seldom”. See Fenton v. Hampton [1858] 11 MOO PC 347.

20. A casus omissus ought not to be created by interpretation, save in some case of strong necessity. Where, however, a casus omissus does really occur, either through the inadvertence of the Legislature, or on the principle quod enim semel aut bis existit praetereunt legislatores, the rule is that the particular case, thus left unprovided for, must be disposed of according to the law as it existed before such statute – casus omissus et oblivioni datus dispositioni communis juris relinquitur; “acasus omissus”, observed Buller, J. in Jones v. Smart 1785 (1) TR 44 : 99 ER 963 (ER p. 967) “can in no case be supplied by a court of law, for that would be to make laws”. The principles were examined in detail in Maulavi Hussein Haji Abraham Umarji v. State of Gujarat [2004] 6 SCC 672.

21. The golden rule for construing all written instruments has been thus stated :

“The grammatical and ordinary sense of the words is to be adhered to unless that would lead to some absurdity or some repugnance or inconsistency with the rest of the instrument, in which case the grammatical and ordinary sense of the words may be modified, so as to avoid that absurdity and inconsistency, but no further.” (See Grey v.Pearson.)

22. The latter part of this “golden rule” must, however, be applied with much caution. “If”, remarked Jervis, CJ.,

“the precise words used are plain and unambiguous, in our judgment, we are bound to construe them in their ordinary sense, even though it do lead, in our view of the case, to an absurdity or manifest injustice. Words may be modified or varied, where their import is doubtful or obscure. But we assume the functions of legislators when we depart from the ordinary meaning of the precise words used, merely, because we see, or fancy we see, an absurdity or manifest injustice from an adherence to their literal meaning”. (See Abley v. Dale, ER p. 525)

23. The above position was highlighted in Sangeeta Singh v. Union of India [2005] 7 SCC 484.

24. It is of significance to note that the conceptual and contextual difference between section 271(1)(c) and section 276C of the Income-tax Act was lost sight of in Dilip N. Shroff’s case (supra).

25. The Explanations appended to section 272(1)(c) of the Income-tax Act entirely indicates the element of strict liability on the assessee for concealment or for giving inaccurate particulars while filing return. The judgment in Dilip N. Shroff’s case (supra) has not considered the effect and relevance of section 276C of the Income-tax Act. Object behind enactment of section 271(1)(e) read with Explanations indicate that the said section has been enacted to provide for a remedy for loss of revenue. The penalty under that provision is a civil liability. Willful concealment is not an essential ingredient for attracting civil liability as is the case in the matter of prosecution under section 276C of the Income-tax Act.”

9.7 Therefore, following the precedent set in Dharmendra Textile Processors (Supra), we hold that mens rea is not an essential element for imposing penalties for breach of civil obligations as held by the ld. CIT(A)/NFAC and finding of the contravention is sufficient to attract penalties under the Income Tax Act, irrespective of the intention behind the contravention.

9.8 Further, the AR of the assessee heavily relied on the judgment of the Hon’ble Supreme Court in the case of Price Waterhouse Coopers (P) Ltd v. Commissioner of Income Tax, Kolkata-I reported in [2012] 25 taxmann.com 400 (SC) which in our view is distinguishable from the present facts & circumstances of the case. In the case of Price Waterhouse Coopers (P) Ltd v. Commissioner of Income Tax, Kolkata-I the issue was where in tax audit report filed by the assessee, it was indicated that provision towards payment of gratuity was not allowable but the assessee failed to add said provision to total income, the apex court held that the penalty is not leviable as all that has happed through a bona fide and inadvertent error. Apart from the fact that the assessee did not notice the error, it was not even noticed by the AO who framed the assessment Order. Further soon after the assessee was communicated the reasons for reopening the assessment, it realized that a mistake had been committed and accordingly the assessee filed a revised return on the same day. Whereas in the present case even in the Audit report filed way before the filing of return of Income, the total revenue expenditure claimed as application of income includes the depreciation claim and the assessee has also claimed the capital expenditure as application of income which amounts to claim of double deduction. Further in the present case as observed by the AO, the assessee had option to rectify its mistake by filing revised return of income as per section 139(5) of the Act and during the proceedings it was noticed by AO that assessee has not filed it voluntarily. More remarkably during the course of Assessment proceedings, as observed by the AO, the assessee submitted that depreciation on assets has not been claimed as application of Income.

9.9 Considering that no cross objection (CO) being filed by the assessee & also considering the totality of the facts of the case & by relying upon the judgment of the Apex Court, we set aside the Order of the ld. CIT(A)/NFAC & sustain the order of the AO in levying the Penalty U/s 270A of the Act by allowing the appeal filed by the Revenue.

10. In the result, the appeal filed by the Revenue is allowed.

Order pronounced in the open court on 30th Dec, 2024