Climate change is primarily attributed to disproportionately high cumulative emissions, both historical and high per capita annual emissions of greenhouse gases (GHGs) of the developed countries. The global nature of the problem makes India one of the most vulnerable regions despite having contributed only about 4 per cent in the cumulative global emissions (for the period 1850-2019) and maintaining its per capita emission at far less than the world average. While India is less responsible for the high stock of emissions, however, it has consistently engaged in demonstrating global leadership towards adopting various measures and ensuring a low-emission growth pathway with a commitment to the net-zero emissions goal by 2070.

India has integrated the development goals with ambitious climate action goals, be it in the form of augmented solar power capacity (installed), higher energy saving targeting notified in PAT cycle-VII, improved green cover facilitated by Green India Mission, among other targeted Government actions. As part of dedicated efforts to preserve ecosystems, India now has 75 Ramsar sites for wetlands, in addition to various regulatory and promotional measures to protect and conserve mangroves. Continued river conservation and rejuvenation efforts are underway through Namami Gange and National River Conservation Plan (NRCP).

In August 2022, the country updated the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) in line with the Hon’ble PM’s vision expressed in the 26th meeting of the Conference of Parties of UNFCCC. In terms of transition to renewable energy sources, India has already achieved its target of 40 per cent installed electric capacity from non-fossil fuels ahead of 2030. It has advanced the target to 50 per cent, which shall also translate to a significant reduction in the average emission rate. The National Hydrogen Mission and Green Hydrogen Policy have been introduced to enable India to be energy independent by 2047. Its pivotal role is also reflected in India’s Long Term Low Emissions Development Strategy (LT-LEDS).

The availability of adequate and affordable finance remains a constraint in India’s climate actions. The country has so far largely met its requirements from domestic sources only. Finance is a critical input for its climate actions. Therefore, the country has scaled up its efforts towards mobilising private capital, including through sovereign green bonds, to meet climate action goals. A framework for the latter has been issued in compliance with International Capital Market Association (ICMA) Green Bond Principles (2021).

India’s initiatives on the international stage have been noteworthy. The country has actively engaged in global actions by championing the formation and strengthening of various intergovernmental organisations.

Introduction

7.1 Climate change is the long-term change in temperature and weather patterns that can occur due to natural reasons, but since the beginning of the industrial revolution in the 19th century, it has been predominantly due to anthropogenic activities. GHG emissions remain in the atmosphere for tens to hundreds of years, trapping the sun’s heat from escaping. While within limits, these make our earth more habitable, allowing for salubrious weather conditions, the enhanced emissions have led to rising temperatures with the potential to bring about sea level rise, change monsoon cycles and impact land systems.

7.2 GHG emissions are the most significant threat to humanity and the inescapable reality the world faces. Action to reduce carbon emissions and adapt to the changing climatic conditions are required urgently as the world has already started to experience its consequences. For instance, it is estimated that by 2030, about 700 million people worldwide will be at risk of displacement by drought alone (U.N. SDG Portal). Thus, global warming is a reality, and so is climate change. Nor is there much doubt that human activity is primarily responsible for it this time, although climate change occurred in the distant past even when Planet Earth was scarcely populated.

7.3 Despite agreement on the above, there can still be much divergence about what comes next and what to do about it when it comes to climate change. Much of the global angst associated with climate change is about the emission of GHGs and carbon, in particular. The more GHGs are emitted, the more they stay trapped in the atmosphere, accelerating global warming. Hence, the argument goes that if some of the cataclysmic consequences are to be avoided, then global warming must be arrested, slowed and, if possible, reversed. One way to strive for it is to reduce emissions of GHG, including carbon. Many nations pledge to reduce their net emission to zero by 2050. Some wish to achieve it by 2060 and by 2070.

Figure VII.1: Net Zero Pledges of countries (the Year pledged is on top of the bars)

Source: Emissions Gap Report 2022, UNEP

7.4 However, this is where things begin to get interesting. Science is not very clear on whether further emission reduction would necessarily guarantee a stoppage or reversal of global warming. The reason being much carbon dioxide and other GHGs have already been emitted over the last two and half centuries of industrialisation-led economic growth in today’s advanced nations, principally in North America and Europe. The share of developing countries in the stock of GHGs (usually measured as carbon dioxide equivalent) has been minimal compared to developed countries. This is corroborated by the Inter-Governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which highlights that the challenges faced due to global warming are mainly due to cumulative historical and current GHG emissions of developed countries. The impact of the accumulation would also be iniquitous, with the developing countries not only bearing the brunt of climate change but also constrained by their capacity to respond to its challenges. The IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) notes that high human vulnerability global hotspots are found particularly in West, Central & East Africa, South Asia, Central, and South America, Small Island Developing States, and the Arctic.

7.5 Further, as per the report, Asia is most vulnerable to climate change, especially to extreme heat, flooding, sea level rise, and erratic rainfall. Ironically, the burden of adaptation is highest for those who have contributed the least to global warming. That unfortunate inevitability means that the stock of GHGs in the atmosphere may have already set a train of events that future emission reduction could do very little to stop or reverse.

7.6 Even if the answer to this question is unclear or unknown, some correctly argue that not doing whatever we can to make the planet more liveable and less dangerous may amount to criminal negligence. The problem is that the people and nations making this argument have their priorities correct for themselves but not for the countries yet to climb the ladder of prosperity. It is an enduring principle of economics that resources have competing uses and that there are always trade-offs.

7.7 Today’s developing nations are therefore caught in the horns of a dilemma. How much resources to devote to bread-and-butter developmental priorities and to adapting to the already changing climate, and how much to dedicate to mitigating emissions of GHGs? Today’s developed nations have prospered through the unrestricted use of fossil fuels, including coal, crude oil, and natural gas. It is theoretically elegant to argue that switching to renewable or non-fossil fuel energy would generate investments and jobs. Still, it seldom works out so smoothly in practice.

7.8 For example, China has declared that future energy supplies, including alternative ones, must be secured first before dispensing with existing energy sources. Countries might find themselves not scrapping coal-fired power plants, and the alternatives may be held up either due to a lack of technology, financial resources, skilled and trained human resources, or some combination of all three. Countries have also learnt that the jobs that are likely to be created in the so-called ‘green economy’ are tilted towards skill and technology-intensive than in traditional industries.1 One may also argue that it may be easier to speak of retraining and relocating people than actually doing so.

7.9 Nobel Laureate Thomas Schelling (2005) argued that the most effective way to combat climate change was to let nations grow first2:

“If per capita income growth in the next 40 years compares with the 40 years just past, vulnerability to climate change should diminish, and the resources available for adaptation should be greater. I say this not to minimise concern about climate change but to anticipate whether developing countries should make sacrifices in their development to minimise the emission of gases that may change the climate to their disadvantage. Their best defence against climate change may be their own continued development.”

7.10 That economic growth would enable resource generation will come as no surprise to students of corporate finance. Companies generate profits and internal resources and thus fund their investments. For companies worldwide, the single biggest source of finance for their capital investments is their own resources before they turn to markets. That would work for nations too.

7.11 Another reason why it is a realistic proposition is that securing funding from either developed nations or multilateral organisations is rather difficult. Public finances in developed countries are stretched and do not seem to have the intent to mobilise adequate resources for climate action in developing countries. They also do not have the appetite to provide additional capital to multilateral institutions for them to be able to lend more or mobilise greater resources. Further, the willingness and incentives-alignment of the private sector to undertake long-gestation projects are questionable at best or non-existent at worst.

7.12 Lastly, it does not seem so strange or irresponsible that developing countries must put their own growth and development aspirations ahead of their global climate obligations when one considers that developed countries set aside their obsessive concerns about climate change and global warming to burn more coal to generate electricity this year. Aiming to reduce their dependence on Russian crude oil and natural gas, countries in Europe had to switch to coal to keep their homes warm and well-lit3. The behaviour of European nations in 2022, eminently understandable, demonstrates the return of energy security as a prime requirement for countries. Therefore, it stands to reason that it would be no different for developing economies too.

7.13 Earlier in the year, the OECD and the Social Economics Lab at Harvard teamed up to understand why policies to address climate change have been difficult to implement and surveyed over 40,000 respondents across 20 of the world’s most carbon-emitting countries (representing 72 per cent of global CO2 emissions). The findings were striking4. In general, citizens in developed countries expressed considerable reluctance to change their lifestyles and habits with respect to driving, flying and eating that would contribute to reduced emissions. Policies to implement carbon pricing have not been easy in all European countries. France tried and retreated in 2018. Switzerland’s proposal was defeated in a referendum in 2021.

7.14 As though these challenges are not enough, many experts also warn of the availability of rare earth elements (REE) and critical minerals (CM) to be the next geopolitical battleground as crude oil has been over the last fifty years.5 As we are aware, REE and CM are essential for generating renewable energy. The problem is that they are produced in a few countries and processed in even fewer countries. A globally synchronised energy transition to non-fossil fuels might be difficult to pull off if adequate REE and CM are not available. That would leave the fossil fuel-based assets stranded for many countries’ economies!

7.15 Jean Pisani-Ferry, associated with the Bruegel Institute and an advisor to the French Government, has begun to sound the alarm about climate change’s significant short-run macroeconomic costs. Citing him in his article for the International Monetary Fund’s ‘Finance and Development’, Daniel Yergin writes6,

“The economist Jean Pisani-Ferry, cofounder of Bruegel, Europe’s leading economic think tank, has observed that accelerating the targets for net carbon emission reductions too aggressively could create much larger economic disruptions than generally anticipated—what he called “an adverse supply shock—very much like the shocks of the 1970s.” Such a transition, Pisani-Ferry presciently wrote in 2021, just before the current energy crisis began, is “unlikely to be benign and policymakers should get ready for tough choices.” He subsequently added, in 2022: “Climate action has become a major macroeconomic issue, but the macroeconomics of climate action is far from the level of rigour and precision that is now necessary to provide a sound basis for public discussions and to guide policymakers adequately. For understandable reasons, advocacy has too often taken precedence over analysis. But at this stage of the discussion, complacent scenarios have become counterproductive. The policy conversation now needs methodical, peer-examined assessments of the potential costs and benefits of alternative plans for action.”

7.16 However, whether we like it or not, the climate change issue will be increasingly relevant and will occupy the airwaves and the attention of policymakers. Countries, even if they wait for financial, technological and human resources for emissions mitigation, have to take action to make their people resilient and adapt to climate change. So, actions on multiple fronts are needed, including the estimation of resources, lifestyle adjustments etc.

7.17 Here, India, considered to be one of the most vulnerable countries given its long coastline, monsoon-dependent agriculture, and large agrarian economy, is one of the leading examples of this. It has contributed only 4 per cent (until 2019) to the cumulative global emissions and its per capita emission is far less than the world average.

7.18 The fact that climate change is a global phenomenon and requires collective efforts has been widely accepted and is the basis of the commitments in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and its Paris Agreement. Recognising the differentiated responsibility of countries (in view of their role in GHG emissions) and the higher developmental needs of the developing countries, they call for a collective action based on the principles of equity and Common But Differentiated Responsibility and Respective Capabilities (CBDR-RC). The collective action has translated into NDCs-through which each country has made a commitment to work towards a collective goal of keeping temperature rise to below 2° C above pre-industrial levels.

7.19 India has been striving to pursue the goal of sustainable development. It spearheads one of the most robust climate actions through its NDCs, which includes an ambitious programme for transitions to clean energy in the world. Despite the adverse impacts of Covid-19 on the economy, the country has enhanced its climate ambition manifold and embarked on a long-term strategy towards a low GHG emission based development.

7.20 Having set the context, this chapter presents an updated discussion on the issue of climate change from India’s perspective, including a discussion on forests and their role in mitigating carbon emissions, an approach to transition to renewable energy and the recently submitted low emissions development strategy. The chapter further presents a discussion on the outcomes of the 27th session of the Conference of Parties (COP 27), progress made on enabling financing for sustainable development and India’s role in global efforts towards addressing climate change. Besides this, recent changes in environmental regulations and other environmental aspects, such as biodiversity and wildlife, are also discussed.

Progress on India’s Climate Action

7.21 India’s climate vision is integrally linked to its vision of development that foregrounds the goals of poverty eradication and guaranteeing basic well-being to all its citizens. Action on addressing climate action was initiated even before the Paris Agreement came into being. In 2008, India launched the National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC), establishing eight National Missions, covering several initiatives and a slew of measures in the area of solar, water, energy efficiency, forests, sustainable habitat, sustainable agriculture, sustaining Himalayan ecosystem, capacity building and research and development (R&D).

Figure VII.2: Progress on Eight National Missions of the NAPCC highlighting achievements across various domains

7.22 National Adaptation Fund for Climate Change (NAFCC), a central sector scheme, was initiated in 2015-16 to support adaptation activities in the States and Union Territories (UTs) of India that are vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change. NAFCC is implemented in project mode, and to date, 30 projects have been sanctioned in 27 States and UTs with a total project cost of ₹847.5 crore. NAFCC supports adaptation action, in, inter alia, agriculture, water, forestry, livestock, and restoring ecosystems. At present (November 2022), 28 projects are under implementation.

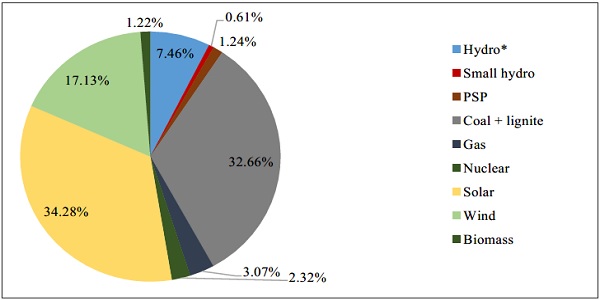

7.23 Demonstrating higher ambition in its climate action, the Government of India submitted its updated NDC on August 26, 2022. The new NDC with enhanced targets translates the vision of the Hon’ble PM expressed through the “Panchamrit” at the UNFCCC Conference of Parties (COP 26) in Glasgow in November 2021. The vision mentions of sustainable lifestyles and climate justice to protect the poor and vulnerable from the adverse impacts of climate change. Aligning with this vision, the share of non-fossil fuel-based capacity in overall capacity has risen rapidly over time. Including the large hydro, the share of non-fossil sources in total installed electricity capacity is estimated to be about 40.4 per cent (on 31.09.2022) compared to 27.3 per cent in 2014-15. This period has seen a sizeable enhancement in the share of installed electricity capacity in solar and wind energy from 8.9 per cent in 2014-15 to 25.1 per cent in 2022-23 (April-Sept).

Box VII.1: India’s updated Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC)

India submitted its first NDC to UNFCCC in October 2015. This was updated in August 2022. The 2015 NDC comprised eight goals, three of which were quantitative targets to be achieved up to 2030. The three targets included cumulative electric power installed capacity from non-fossil sources to reach 40 per cent, reduction in the emissions intensity of GDP by 33 to 35 per cent compared to 2005 levels, and creation of additional carbon sink of 2.5 to 3 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent through additional forest and tree cover.

Article 4 of the Paris Agreement provides that each Party shall communicate or update its NDC every five years. Therefore, in accordance with the aforesaid provision of the Paris Agreement, India submitted the following updates to its first NDC of 2015.

1. To put forward and further propagate a healthy and sustainable way of living based on traditions and values of conservation and moderation, including through a mass movement for ‘LIFE’– ‘Lifestyle for Environment’ as a key to combating climate change.2.

2. To adopt a climate-friendly and cleaner path than the one followed hitherto by others at the corresponding level of economic development.

3. To reduce the Emissions Intensity of its GDP by 45 per cent by 2030, from the 2005 level.

4. To achieve about 50 per cent cumulative electric power installed capacity from non-fossil fuel-based energy resources by 2030, with the help of the transfer of technology and low-cost international finance, including from the Green Climate Fund (GCF).

5. To create an additional carbon sink of 2.5 to 3 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent through additional forest and tree cover by 2030.

6. To better adapt to climate change by enhancing investments in development programmes in sectors vulnerable to climate change, particularly agriculture, water resources, the Himalayan region, coastal regions, and health and disaster management.6.

7. To mobilise domestic and new & additional funds from developed countries to implement the above mitigation and adaptation actions in view of the resource required and the resource gap.7.

8. To build capacities and create a domestic framework and international architecture for quick diffusion of cutting-edge climate technology in India and for joint collaborative R&D for such future technologies.

Source: Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change

Status of Forest and Tree Cover

7.24 One of the three quantifiable targets of India’s NDC is to achieve an additional carbon sink of 2.5 billion to 3.0 billion tonnes through additional forest and tree cover by 2030. The forest and tree cover in India has shown a gradual and steady trend of increase in the last one and a half decades.

7.25 he country ranks third globally with respect to the net gain in average annual forest area between 2010 and 2020. This gain is mainly attributed to the robust framework and policies of the National and State Governments that have promoted and safeguarded forests. Schemes like the Green India Mission (GIM), Compensatory Afforestation Fund Management and Planning Authority (CAMPA), National Afforestation Programme (NAP), Green Highway Policy – 2015, Policy for enhancement of Urban Greens, National Agro-forestry Policy, and Sub-Mission on Agro-forestry (SMAF), etc. are among the most important ones.

Carbon Stock in India’s Forest and Tree Cover

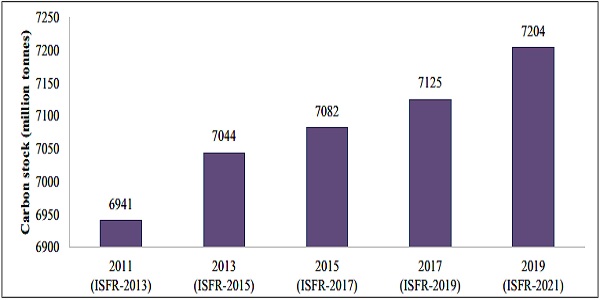

7.26 A robust forest ecosystem is a vital sink of carbon. Forest Survey of India (FSI) assessed the carbon stock (which is the amount of carbon sequestrated from the atmosphere and stored in biomass, deadwood, soil, and litter in the forest) in India’s forests for the first time in 2004 and then biennially since 2011. The Indian State of Forest Report (ISFR) estimates the carbon stock of forests to be about 7,204 million tonnes in 20197, which is an increase of 79.4 million tonnes of carbon stock as compared to the estimates of the previous assessment for 2017. This translates into carbon emissions sequestrated through forest and tree cover to be 30.1 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent.

Figure VII.3: Carbon stock in forests in India has been rising

Source: Based on data of the Forest Survey of India

7.27 Among the Indian States, Arunachal Pradesh has the maximum carbon stock in forests (1023.84 million tonnes), followed by Madhya Pradesh (609.25 million tonnes). The per-hectare forest carbon stock among different States/UTs indicates that Jammu & Kashmir is contributing the maximum per-hectare carbon stock of 173.41 tonnes, followed by Himachal Pradesh (167.0 tonnes), Sikkim (166.2 tonnes) and Andaman & Nicobar Islands (162.9 tonnes).

Preservation of Ecosystems: A Critical Adaptation Action

7.28 Ecosystems play an important role in carbon storage, protect the coastal areas, and enhance water quality besides other services, such as cultural, spiritual or tourist attractions. Wetlands are natural buffers against floods, droughts, and tropical cyclones. Wetlands can act as sponges, storing peak rainfall and releasing water gradually during the lean season. The floods in Kashmir Valley in September 2014 and Chennai city in December 2015 are reminders of the ways wetland destruction can make lives vulnerable. The Ramsar Convention, signed on February 2, 1971, is one of the oldest inter-governmental accords signed by member countries to preserve the ecological character of their wetlands of international importance. Wetlands declared as Ramsar sites are protected. India has 75 Ramsar sites covering an area of 13.3 lakh ha, and 49 of these have been added in the last 8 years.

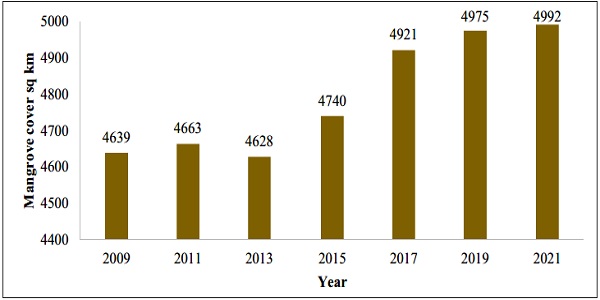

7.29 Mangroves and coastal wetlands form the first line of defence for coastal communities against increased storm surges, flooding, and hurricanes. As per a recent study, certain mangrove species in Chilika and Sundarbans along the east coast and Dwarka and Porbandar along the west coast of India are likely to reduce and shift landward by 2070 due to a decline in suitable habitats in response to precipitation and sea level changes.

7.30 The Government has taken both regulatory and promotional measures to protect and conserve mangroves. The National Coastal Mission Programme on ‘Conservation and Management of Mangroves and Coral Reefs’ is being implemented. Regulatory measures are implemented through Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) Notification (2019) under the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986; the Wild Life (Protection) Act, 1972; the Indian Forest Act, 1927; the Biological Diversity Act, 2002; and rules under these acts as amended from time to time. As per the ISFR 2021, the mangrove cover in the country has increased by 364 sq. km. in 2021 as compared to 2013.

Figure VII.4: Increasing Mangrove cover in India

Source: ISFR 2021

River Conservation and Rejuvenation

7.31 The Government is working on mapping and converging the 5Ps’ – People, Policy, Plan, Programme and Project. It has been supplementing the efforts of the States/Union Territories (UTs) by providing financial and technical assistance for the abatement of pollution in identified polluted stretches of rivers in the country through the Central Sector Scheme of Namami Gange for River Ganga and its tributaries, and the Centrally Sponsored Scheme of National River Conservation Plan (NRCP) for other rivers.

7.32 In addition, the government has recently released Detailed Project Reports (DPR) for the rejuvenation of 13 major rivers prepared by the Indian Council of Forestry Research and Education (ICFRE), Dehradun in consultation with the State Forest Departments and other line Departments. Works proposed under these DPRs include afforestation on riverbanks leading to increased green cover, measures to contain soil erosion, recharge the groundwater table, sequester carbon dioxide, catchment area treatment, ecological restoration, moisture conservation, livelihood improvement & income generation, etc.

Approach to Transition to Renewable Energy Sources

7.33 While the target was to achieve 40 per cent of the installed electric capacity from non-fossil fuel sources by 2030 in the initial NDC submitted in 2015, the target has already been achieved. India is now striving to achieve the target of 50 per cent cumulative electric power installed capacity from non-fossil fuel-based energy resources by 2030, in line with updated NDCs.

Figure VII.5: Increasing installed Electricity Generation Capacity with a rising share of non- fossil fuel-based capacity

Source: Based on data from the Ministry of Power.

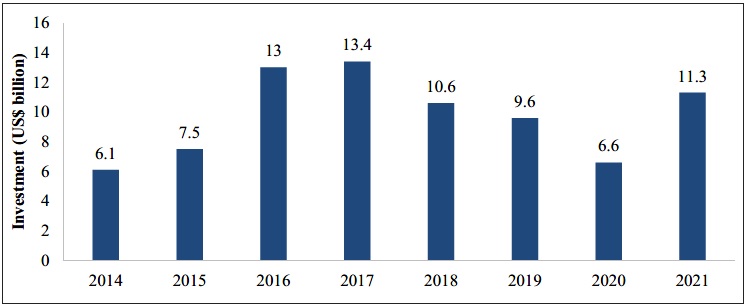

7.34 India is progressively becoming a favoured destination for investment in renewables. As per the Renewables 2022 Global Status Report, during the period 2014 -2021, total investment in renewables stood at US$ 78.1 billion in India. Investment in renewable energy has been close to or higher than US$ 10 billion per year since 2016, except for a dip in 2020 likely due to various Covid-19 restrictions.

Figure VII.6: Investment in Renewables in India since 2

Source: REN 21. Renewables 2022 Global Status Report

7.35 The Central Electricity Authority (CEA) has projected the optimal generation capacity mix to meet the peak electricity demand and electrical energy requirement for 2029-30. The estimate builds in improved efficiency and minimises the total system cost subject to various technical/financial constraints. The likely installed capacity by the end of 2029-30 is expected to be more than 800 GW of which non-fossil fuel would be more than 500 GW.

Figure VII.7: Projected optimal mix of installed capacity for 2029-30

Source: Central Electricity Authority

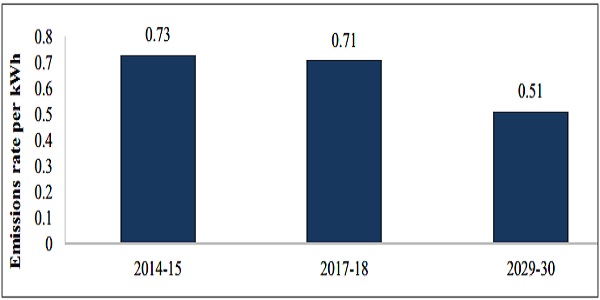

7.36 Moreover, the CEA has also estimated that the average emission rate will decline by around 29 per cent by 2029-30 compared to 2014-15.

Figure VII.8: Projected fall of average CO2 emissions rate per kWh of electricity due to significant additions in non fossil fuel-based installed capacity

Source: Based on data of the Central Electricity Authority

7.37 From the emerging global momentum on green hydrogen, India can situate this decarbonisation opportunity not just within the context of a low-carbon economy but also as an enabler of energy security and economic development for the nation. It will be crucial for achieving decarbonisation of harder-to-abate sectors such as fertilisers, refining, methanol, maritime shipping, iron & steel and long-haul transport. Green hydrogen is also an important element of India’s Long Term Low Emissions Development Strategy (LT-LEDS).

7.38 With a vision to make India an energy-independent nation, and to de-carbonise critical sectors, the Government approved the National Green Hydrogen Mission on January 4, 2023 with an initial outlay of ₹19,744 crore. The Mission will facilitate demand creation, production, utilisation and export of Green Hydrogen and mobilisation of over ₹8 lakh crore of investment by 2030.

Figure VII.9: Salient Features of the National Green Hydrogen Mission

Source: Ministry of New & Renewable Energy

7.39 A report by NITI Aayog9 in June 2022 shows that in the case of India, renewable tariffs have fallen in recent years, and electrolyser costs are expected to fall in the future. A recent report by the International Renewable Energy Agency (2020)10 suggests that the cost of electrolysers is crucial for making green hydrogen economically viable. The report also underscores the importance of innovation in electrolyser technology and the rapid increase in its scale of production as the main factors that would drive down the cost of electrolysers and green hydrogen.

7.40 NITI’s report estimates that the cumulative value of the green hydrogen market in India will be US$ 8 billion by 2030 and US$ 340 billion by 2050. The electrolyser market will be approximately US$ 5 billion by 2030 and US$ 31 billion by 2050. In addition, the adoption of green hydrogen will also result in 3.6 Giga tonnes of cumulative CO2 emission reduction by 2050. This will also generate enormous energy import savings, ensure stability in industry input prices, and strengthen foreign exchange reserves in the long run.

Figure VII.10: Falling Levelised Cost of Hydrogen (LCOH11) for green hydrogen

Source: NITI Aayog

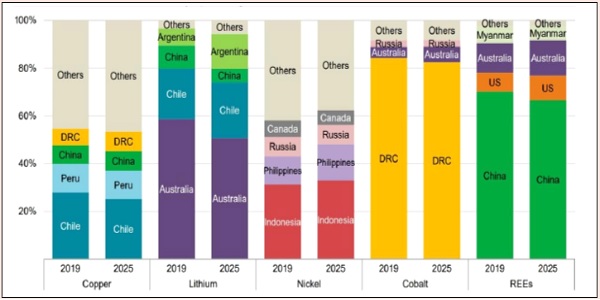

7.41 However, all this is based on the assumption that access to critical minerals essential for renewable energy at a reasonable cost will continue-an assumption that could be an effective constraint in the face of the concentration of these minerals in certain geographies with a monopoly in access to some countries.

Box VII.2: Critical Minerals-Key to Green Transition

The shift to a clean energy system is set to drive a huge increase in the requirements for critical minerals. This is because an energy system powered by clean energy technologies differs profoundly from one fuelled by traditional hydrocarbon resources. Cobalt, copper, lithium, nickel, and rare earth elements (REEs) are critical for producing electric vehicles and batteries and harnessing solar power and wind energy. Solar photovoltaic (PV) plants, wind farms and electric vehicles (EVs) generally require more minerals than their fossil fuel-based counterparts. A typical electric car requires six times the mineral inputs of a conventional car, and an onshore wind plant requires nine times more mineral resources than a gas-fired plant12.

The types of mineral resources used vary by technology. Lithium, nickel, cobalt, manganese and graphite are crucial to battery performance, longevity and energy density. REEs are essential for permanent magnets that are vital for wind turbines and EV motors. Electricity networks need a huge amount of copper and aluminium, with copper being a cornerstone for all electricity-related technologies.

While the demand for critical minerals is set to increase because of the global preference and emphasis towards renewable energy, the global supply chain of the critical minerals is highly concentrated and unevenly distributed. The skewed distribution of the resource poses a supply risk in the face of its enhanced demand.

Figure VII.11: Concentration of production of selected minerals in 2019 and 2025

Source: International Energy Agency Report on ‘The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions’

A carefully crafted multi-dimensional mineral policy would reduce our dependence and address the problems for the future. The country has resources of nickel, cobalt, molybdenum, and heavy REEs, but further exploration would be needed to evaluate the quantities of their reserves. There is a need to create strategic mineral reserves along the lines of strategic petroleum reserves to ensure a continuous supply of minerals. Also, policies should consider investing in internal research including technological innovation for mineral exploration and processing and the development of Recycling, Reusing, and Repurposing (R3) technologies.

In order to ensure the mineral security of the nation and to attain self-reliance in the area of critical and strategic minerals, the Ministry of Mines has created a Joint Venture company, namely Khanij Bidesh India Ltd (KABIL), with participating interests of NALCO, HCL and MECL. KABIL is mandated to identify and acquire overseas mineral assets of critical and strategic nature, such as Lithium, Cobalt etc. Further, the Ministry of Mines, Government of India and the Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources (DISER), Government of Australia, signed an MoU on June 3, 2020 for cooperation in the field of mining and processing of critical and strategic minerals. Further, KABIL has also signed a detailed MoU with a collaborative framework with the Critical Minerals Facilitation Office under the DISER on March 10, 2022 to identify lithium and cobalt mineral assets for final joint investment decisions and acquisition of the assets in Australia catering to the critical and strategic ecosystem of both the countries.

Long-Term Low Emissions Development Strategy (LT-LEDS)

7.42 India submitted its Long-Term Low Carbon Development Strategy (LT-LEDS) on November 14, 2022, at COP 27. The salient features of LT-LEDS are:

- Focus on the rational utilisation of national resources with due regard to energy security. The transitions from fossil fuels will be undertaken in a just, smooth, sustainable and all-inclusive manner.

- Encompasses the objectives of the National Hydrogen Policy. The rapid expansion of green hydrogen production, increasing electrolyser manufacturing capacity in the country, and a three-fold increase in nuclear capacity by 2032 are some of the other milestones that are envisaged alongside the overall development of the power sector.

- Increased use of biofuels, especially ethanol blending in petrol. The drive to increase electric vehicle penetration, and the increased use of green hydrogen fuel are expected to drive the low carbon development of the transport sector. India aspires to maximise the use of electric vehicles, ethanol blending to reach 20 per cent by the Ethanol Supply Year 2025-26, and a strong modal shift to public transport for passengers and freight.

- Climate-resilient urban development will be driven by smart city initiatives, integrated planning of cities for mainstreaming adaptation and enhancing energy and resource efficiency, effective green building codes and developments in innovative solid and liquid waste management.

- India’s industrial sector will continue on a strong growth path, with the vision of‘Aatmanirbhar Bharat’ and ‘Make in India’.

7.43 LT-LEDS has been prepared in the framework of India’s right to an equitable and fair share of the global carbon budget and is the practical implementation of India’s call for “climate justice.” This is essential to ensure that there are no constraints on realising India’s vision of rapid growth and economic transformation while protecting the environment. The LT-LEDS is driven by the vision of LiFE, Lifestyle for the Environment that calls for a worldwide paradigm shift from mindless and destructive consumption to mindful and deliberate utilisation. Here, the transition to low carbon development pathway will entail costs. In addition, the provision for climate finance by developed countries will play a very significant role and, therefore, needs to be considerably enhanced in the form of grants and concessional loans.

Finance for Sustainable Development

7.44 Finance is a critical input in India’s climate actions. The country’s climate actions have so far been largely financed from domestic sources, including government budgetary support, a mix of market mechanisms, fiscal instruments, and policy interventions. India has shown global leadership in the fight against climate change and has committed itself to achieving net-zero emissions by 2070. While several estimates of the required investments are indicated in the LT-LEDS report prepared by India, it is important to note that all allude to a need for tens of trillions of US dollars.

7.45 The understanding in the Convention and the Paris Agreement has been that the developed countries will mobilise the resources through public and other sources, including by catalysing private finance to enable a flow of financial resources at a reasonable cost. While these are yet to materialise, India has scaled up its efforts towards greater mobilisation of private capital to meet its ambitious climate action goals.

Green Bonds

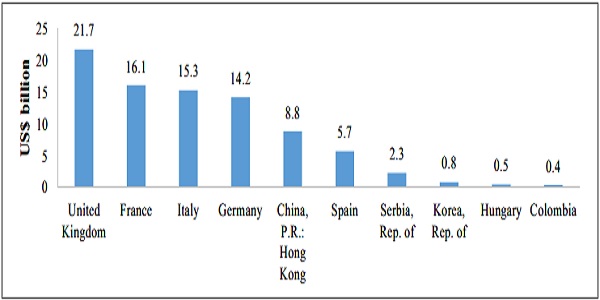

7.46 Green bonds are financial instruments that generate proceeds for investment in environmentally sustainable and climate-suitable projects. With the growing focus on the environmental sustainability of projects, green bonds have become widely accepted as an instrument to raise funds to support climate and environmental projects and command a relatively lower cost of capital vis-à-vis regular bonds. Major countries that resorted to green bonds to raise funds include the UK, France, Germany, the USA, and China. IMF data indicates that green bonds of value around US$ 620 billion were issued across the world in the year 2021, in which countries issued green bonds of value US$ 587.7 billion and international organisations issued bonds of value US$ 32.3 billion. As per SEBI’s data on green debt securities, during the period of 2017 to September 2022, 15 Indian corporates have issued green bonds of value ₹4,539 crore. Most of these are related to renewable energy generation, while one is slated to be used for the tertiary treatment of wastewater.

Figure VII.12: Status of Sovereign Green Bond issuances in 2021

Source: Emissions Gap Report 2022, UNEP

7.47 In keeping with the ambition to reduce the carbon intensity of the economy significantly, the Union Budget 2022-23 announced the issue of Sovereign Green Bonds. The issuance of Sovereign Green Bonds will help the government to tap the requisite finance from potential investors for deployment in public sector projects aimed at reducing the carbon intensity of the economy. The final Sovereign Green Bonds framework of India has been issued. The Framework has been designed to comply with the components and key recommendations of the International Capital Market Association (ICMA) Green Bond Principles (2021).

7.48 A Green Finance working committee has also been set up to oversee and validate key decisions on the issuance of Sovereign green bonds. The committee has the mandate to select the projects for allocation of proceeds, do a time-bound review of the allocation and carry out annual reporting along with an impact assessment of the proceeds from sovereign green bonds issued.

7.49 The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has notified the indicative calendar for the issuance of Sovereign Green Bonds (SGrBs) for the fiscal year 2022-23. The issuance would take place through two auctions on January 25, 2023 and February 9, 2023, respectively, for ₹8,000 crore each, totalling ₹16,000 crore. The security-wise allocation would include 5 year and 10 year SGrBs for ₹4,000 crore each for both auctions. Five per cent of the notified amount of sale has been reserved for retail investors as specified under the ‘Scheme for Non-competitive Bidding Facility in the auction of Government of India Dated Securities and Treasury Bills’. The SGrBs will be designated as specified securities under the ‘Fully Accessible Route’ for investment in Government Securities by non-residents. Over time, the SGrBs would provide a pricing reference for private sector entities in India for their domestic borrowings through Environment, Social, and Governance (ESG) bonds. Thus, the issuance of SGrBs would help in creating an ecosystem which fosters a greater flow of capital into green projects and entities undertaking such projects.

7.50 On November 3, 2021, the RBI published its ‘Statement of Commitment to Support Greening India’s Financial System’ – NGFS. Here, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) laid out, keeping in view its national commitments, priorities, and complexity of our financial system, committed to, among others, exploring how climate scenario exercises can be used to identify vulnerabilities in RBI-supervised entities’ balance sheets, business models and gaps in their capabilities for measuring and managing climate-related financial risks. Also, in 2007, the RBI advised banks to put in place an appropriate action plan for making a meaningful contribution to sustainable development. Over time, RBI has incentivised bank lending towards greener industries and projects. For example, renewable energy projects have been included under Priority Sector Lending (PSL). The RBI has also been spreading awareness on the issue of green and sustainable finance by discussing the opportunities and challenges of green finance through its publications and other communication.

7.51 SEBI introduced the regulatory framework for issuance of green debt securities as a mode of sustainable finance under the erstwhile SEBI (Issue and Listing of Debt Securities) Regulations, 2008, (ILDS Regulations), vide circular dated May 30, 2017.

7.52 At the time of review of the ILDS Regulations, the provisions of the erstwhile circular were subsumed, and the definition of “green debt security” was incorporated as Regulation 2(1)(q) in the SEBI (Issue and Listing of Non-Convertible Securities) Regulations, 2021 (‘NCS Regulations’). The disclosure requirements were prescribed vide Operational Circular dated August 10, 2021.

7.53 Recently, vide a circular dated November 24, 2022, SEBI has allowed an issuer under the SEBI (Issue and Listing of Municipal Debt Securities) Regulations, 2015 (‘ILMDS Regulations’) to issue a green debt security if it falls within the definition of “green debt security” as per Regulation 2(1)(q) of the NCS Regulations. Such an issuer has to comply with both ILMDS Regulation and NCS Regulations.

7.54 In the backdrop of increasing interest in sustainable finance in India as well as around the globe, and with a view to aligning the extant framework for green debt securities with the updated Green Bond Principles recognised by International Organisation of Securities Commission (IOSCO), SEBI undertook a review of the regulatory framework for green debt securities. Based on the review, it has been decided in the SEBI board meeting dated December 20, 2022, to:

a. Enhance the scope of the definition of green debt security by including new modes of sustainable finance in relation to pollution prevention and control, eco-efficient products, etc.;

b. Introduce the concept of blue bonds (related to water management and marine sector), yellow bonds (related to solar energy) and transition bonds as subcategories of green debt securities.

Investing in Resilience for Sustainable Development

7.55 SEBI has been one of the early adopters of sustainability reporting for listed entities and requires mandatory ESG-related disclosures for the top 100 listed entities (by market capitalisation) since 2012. Over the years, the requirement was strengthened to cover the top 500 and then the top 1000 entities. SEBI has issued new sustainability reporting requirements under the Business Responsibility and Sustainability Report (BRSR), which are more granular with quantifiable metrics in line with the principles ensconced in the ‘National Guidelines on Responsible Business Conduct’. The BRSR was made mandatory for the top 1000 listed entities (by market capitalisation) from 2022–23. Early research show that for top Indian firms, ESG performance reduced stock return volatility during Covid-1913 and enabled firms to access capital at lower cost by building investors’ confidence as ESG disclosures create long-term value for investors as well as reduce information asymmetry14.

7.56 The COP 27 to the UNFCCC was held from 6 to 20 November 2022 in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt. In conjunction with COP 27, the 17th Session of the Conference of Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol (CMP17), the 4th Session of the Conference of the Parties serving as the Meeting of Parties to Paris Agreement (CMA4), 57th session of the Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA) and the Subsidiary Body for Implementation (SBI) were also held.

7.57 India participated in COP 27, with a focus on mainstreaming the theme of LiFE – Lifestyle for Environment. The Indian Pavilion at COP 27 highlighted the theme of LiFE in various ways – models, audio-visual displays, activities, and 49 side events. India invited all countries to join the LiFE movement, which is a pro-people and pro-planet effort seeking to shift the world from mindless and wasteful consumption to mindful and deliberate utilisation of natural resources.

7.58 The cover decision of COP 27, titled the Sharm el-Sheikh Implementation Plan, notes the ‘importance of the transition to sustainable lifestyles and sustainable patterns of consumption and production for efforts to address climate change’. Other decisions were setting up the Just Transition and Mitigation Work Program and the agreement on Joint work on the implementation of climate action on agriculture and food security to be conducted over four years.

7.59 During COP 27, developing nations strongly voiced setting up a separate fund for loss and damage. After negotiations, it was decided to establish new funding arrangements for assisting developing countries that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change in responding to loss and damage, with a focus on addressing loss and damage. A transitional committee has been established to work out the modalities.

7.60 Other substantive elements covered in the Sharm el-Sheikh Implementation Plan are the importance of science in guiding climate action, doubling adaptation finance, dialogue on making finance flows consistent with low-emissions, and climate-resilient development calls on Multilateral Development Banks (MDB) reform for delivering climate finance at scale; diversity of sources of finance (including new and additional finance), etc. COP 27 also saw progress on adaptation, with governments agreeing on how to move forward on the Global Goal on Adaptation, which will conclude at COP 28 and inform the first Global Stocktake in 2023.

7.61 Lastly, during COP 27, it was also recognised that the target of US$ 100 billion per year is yet to be achieved. The COP 21 decided that, prior to 2025, a New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) on climate finance from a floor of US$ 100 billion per year, taking into account the needs and priorities of developing countries, shall be set. To further the agenda of setting the NCQG by 2024, COP 27 decided that Four Technical Expert Dialogues (TEDs) will be carried out prior to COP 28.

India’s Initiatives at the International Stage

International Solar Alliance (ISA)

7.62 The International Solar Alliance (ISA) is a treaty-based inter-governmental organisation working to create a global market system to tap the benefits of solar power and promote clean energy applications. ISA’s mission is to unlock US$ 1 trillion of investments in solar by 2030 while reducing the cost of the technology and its financing. With the signing and ratification of the ISA Framework Agreement by 15 countries on 6 December 2017, ISA became the first international intergovernmental organisation to be headquartered in India. ISA is partnering with multilateral development banks (MDBs), development financial institutions (DFIs), private and public sector organisations, civil society, and other international institutions to deploy cost-effective and transformational solutions through solar energy, especially in the least Developed Countries (LDCs) and the Small Island Developing States (SIDS).

7.63 The ISA has expanded its coverage to all its 110 member countries. It assists them with the adoption of solar energy with the view to improving energy access, ensuring energy security and facilitating the energy transition. Through the programmatic support offered by ISA, a pipeline of 9.5 GW of solar energy capacity has been identified in its member countries, including large-scale solar parks in multiple developing countries. In its member countries, with a grant of US$ 50,000, ISA is assisting in setting up solar energy demonstration projects. Three such demonstration projects were inaugurated at the Fifth Assembly of ISA.

Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure

7.64 The CDRI was launched by the Hon’ble Prime Minister of India during the United Nations Climate Action Summit on 23 September 2019 in New York. It is a global partnership of National Governments, UN agencies and programmes, multilateral development banks and financing mechanisms, the private sector, and academic and knowledge institutions. It aims to promote the resilience of infrastructure systems to climate and disaster risks, thereby ensuring sustainable development.

7.65 As on 29 June 2022, thirty-one Countries, six International Organisations and two private sector organisations have joined as members of CDRI. CDRI has been expanding its membership consistently by attracting a wide variety of economically advanced countries, developing countries, and countries that are most vulnerable to climate change and disasters. Over a period, a network of organisations/stakeholders will be developed to advance disaster-resilient infrastructure not only in India but in other partner countries as well.

Leadership Group for Industry Transition (LeadIT)

7.66 The LeadIT gathers countries and companies that are committed to action to achieve the Paris Agreement. It was launched by the governments of Sweden and India at the UN Climate Action Summit in September 2019 and is supported by the World Economic Forum. LeadIT members subscribe to the notion that energy-intensive industries can and must progress on low-carbon pathways, aiming to achieve net-zero carbon emissions.

7.67 During COP 27, LeadIT members adopted a joint statement wherein members collectively agreed to:

(i) promote value chain partnerships and material circularity;

(i) invest and cooperate on the planning and implementation of infrastructure to support energy and industry transitions;

(iii) give multilateral development banks and multilateral climate funds mandates to de-risk investments in the transition of heavy industries in emerging and developing countries;

(vi) formulate roadmaps for heavy industry sectors that include regulatory frameworks, incentives, and long-term strategies, to facilitate transition finance and attract private investments.

Initiatives Related to other Environmental Issues

Ensuring the Conservation of Biodiversity

7.68 Conservation of biodiversity is crucial as it provides resources and services necessary for human beings and for the sustenance of all living beings. It enhances ecosystem productivity, where each species, however small, has an important role to play. May 22nd is celebrated as an International Day for Biological Diversity every year globally to create awareness among the citizens and stakeholders on the importance and need for the conservation of biological diversity.

7.69 India ranks eighth in the world and fourth in Asia among the mega-diverse countries in the world. It is also rich in fauna, and nearly 62 per cent of the recorded amphibian species are endemic to India, which is majorly found in the Western Ghats. Globally, India holds the eighth position for the origin and diversity of crop plants, as it has more than 300 wild ancestors and close relatives of cultivated plants growing naturally. Notably, around 9,500 plant species are used as medicine in indigenous health practices. Moreover, local and indigenous people use more than 3,900 plant species as food, fibre, fodder, insecticides and pesticides, gum, resins, dyes, perfumes, and timber.

7.70 The 1992 Earth Summit held at Rio de Janeiro led to the adoption of an internationally binding legal instrument, the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), with the objectives of conservation, sustainable use, and fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the use of biological diversity. The fifteenth meeting of the Conference of Parties (COP 15) to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) took place between 7th and 19th December 2022 in Montreal, Canada. Key outcomes of the COP 15 include-

- Effective conservation and management of at least 30 per cent of the world’s lands, inland waters, coastal areas, and oceans. Currently, 17 per cent and 10 per cent of the world’s terrestrial and marine areas are under protection.

- Reduce to near zero the loss of areas of high biodiversity importance.

- Cut global food waste in half and significantly reduce overconsumption and waste generation.

- Reduce by half both excess nutrients and the overall risk posed by pesticides and highly hazardous chemicals.

- Progressively phasing out or reforming subsidies that harm biodiversity by 2030 by at least US$500 billion per year while scaling up positive incentives for biodiversity’s conservation and sustainable use.

- Mobilise by 2030 at least US$ 200 billion per year in domestic and international biodiversity-related funding from all sources – public and private.

- Raise international financial flows from developed to developing countries, in particular, least developed countries, small-island developing States, and countries with economies in transition, to at least US$ 20 billion per year by 2025 and to at least US$ 30 billion per year by 2030.

7.71 In conformity with the spirit of the CBD, India enacted the Biological Diversity Act in 2002. The Act mandates the implementation of the objectives through a decentralised system with the National Biodiversity Authority at the national level, the State Biodiversity Boards at the State level, and Biodiversity Management Committees at the local body level. Each of these entities is a statutory and autonomous body with specific mandates and powers to facilitate the effective implementation of the provisions of the Act and the Rules.

7.72 India and Nepal signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) in August 2022 on biodiversity conservation to strengthen and enhance the coordination and cooperation in the field of forests, wildlife, environment, biodiversity conservation, and climate change, including restoration of corridors and interlinking areas and sharing knowledge and best practices between the two countries. The MoU would help promote cooperation between the Parties in the field of forests, wildlife, environment, biodiversity conservation, and climate change, including restoration of corridors and interlinking areas and sharing knowledge and best practices.

Box VII.3: Project Cheetah

The introduction of Cheetahs in India is being done under Project Cheetah, the world’s first intercontinental large wild carnivore translocation project. The cheetah was declared extinct from India in 1952. Under the scheme, eight Namibian wild cheetahs were introduced on 17 September 2022 in Kuno National Park, Madhya Pradesh. Out of the eight Cheetahs, there are five female and three male Cheetahs.

The historic reintroduction of Cheetahs in India is part of a long series of measures for ensuring sustainability and environmental protection. Cheetahs can help restore open forest and grassland ecosystems in India. This will help conserve biodiversity and enhance the ecosystem services like water security, carbon sequestration, and soil moisture conservation, benefiting society. This effort, in line with the Prime Minister’s commitment to environmental protection and wildlife conservation, will also lead to enhanced livelihood opportunities for the local community through eco-development and ecotourism activities.

The Government has constituted a Task Force for monitoring Cheetah introduction. The Task Force shall be in force for a period of two years. The Task Force has been formed to:

- Review, progress, and monitor the health status of Cheetah, upkeep of the quarantine & soft release enclosures, protection status of the entire area, adherence to the defined protocols by forest & veterinary officials, and advice on Cheetah introduction in India concerning overall health, behaviour and their upkeep.

- Monitor hunting skills and adaptation of Cheetahs to the habitat of Kuno National Park.

- Monitor the release of Cheetah from Quarantine bomas to soft-release enclosures, grassland, and open forest areas.

- Open Cheetah habitat for eco-tourism and suggest regulations in this regard.

- Suggest and advise on developing tourism infrastructure in the fringe areas of Kuno National Park and other Protected Areas.

Wildlife – Its Preservation and Protection

7.73 India has a rich heritage of wildlife and a long history and tradition of conservation. The concern for wildlife is, indeed, the concern for the man himself. All forms of life – human, animal and plants are so closely interlinked that disturbance in one leads to an imbalance in others. A comprehensive legislation was enacted in 1972 called the Wildlife (Protection) Act 1972 to provide special legal protection to our wildlife and the endangered species of fauna.

7.74 Animals such as tigers, lions, and elephants are keystone and flagship species whose preservation benefits the entire ecosystems. As of 10 August 2022, India is home to 53 Tiger Reserves covering approximately 75,796.8 sq. km area in 18 States, with about 75 per cent of the wild tiger population at the global level. India achieved the goal of doubling the tiger numbers in 2018, four years before the targeted year 2022. In addition, 17 Tiger Reserves in the country have CA|TS international accreditation, and two have received International Tx2 Award15.

7.75 Similarly, the population of Asiatic Lions has shown a steady increase, with a population of 674 individuals (2020), 28.87 per cent (one of the highest growth rates so far) higher than the 523 lions in 2015. India now (2020) has 12,852 leopards compared to the previous estimate of 7910 conducted in 2014. More than a 60 per cent increase in population has been recorded. The current population estimates indicate about 50,000 – 60,000 Asian elephants worldwide. More than 60 per cent of the population is in India. Indian Elephant has also been listed in Appendix I of the Convention of the Migratory species in the Conference of Parties of CMS 13 at Gandhi Nagar, Gujarat, in February 2020.

Figure VII.13: Success story of tiger conservation efforts reflected in increased tiger countFigure

Source: National Tiger Conservation Authority

Figure VII.14: Rising lion count over the years, driven by various conservation efforts

Rising lion count over

7.76 The Act has been amended multiple times to strengthen conservation measures and fulfil multilateral commitments on wildlife preservation. Targeting further reforms in wildlife conservation, the government has brought in the Wild Life (Protection) Amendment Act, 2022. The Act seeks to increase the number of species protected under the law and implement the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora16 (CITES). The Wild Life (Protection) Act 1972 has six schedules. The Act aims to rationalise the schedules by (i) reducing the number of schedules for specially protected animals to two, (ii) removing the schedule for vermin species, and (iii) inserting a new schedule for specimens listed in the Appendices under CITES (scheduled specimens). Lastly, the Act empowers the government to regulate or prohibit the import, trade, possession or proliferation of invasive alien species.

Plastic Waste Management and Elimination of Identified Single-Use Plastics

7.77 India is committed to mitigating pollution caused by littered single-use plastics. According to a report on Plastic Waste Management released by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, the global average of plastic per capita consumption is 28 kg, and India has a per capita plastic consumption of 11 kg. However, as an attempt to reduce pollution caused due to littered plastic waste in the country, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Government of India, notified the Plastic Waste Management Amendment Rules, 2021, on August 12, 2021. On July 1, 2022, a ban was imposed on the manufacture, import, stocking, distribution, sale and use of identified single-use plastic items, which have low utility and high littering potential, all across the country. The measures will promote a circular economy, reduce the plastic footprint of plastic packaging, promote the development of new alternatives to plastic packaging and provide the next steps for moving towards sustainable plastic packaging by businesses.

7.78 The following domestic regulatory actions were taken in 2022:

i. The Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change notified the Guidelines on Extended Producer Responsibility for plastic packaging vide Plastic Waste Management Amendment Rules, 2022, on 16 February 2022. The key highlights of the Guidelines on Extended Producers Responsibility (EPR) on plastic packaging notified on February 16, 2022 are:

(a) mandatory registration of Producers, Importers, and Brand Owners (PIBOs) and Plastic Waste Processors (PWPs) through a centralised online portal;

(b) coverage of four categories of plastic packaging viz. rigid, flexible, multi-layered plastic packaging, and compostable plastic packaging;

(c) clearly defined targets for EPR;

(d) mandatory targets for reuse of rigid plastic packaging, minimum level of recycling of plastic waste and use of recycled plastic content in plastic packaging;

(e) centralised online portal to support the implementation of EPR;

(f) provision for the sale and purchase of surplus EPR certificates;

(g) levy of environmental compensation for non-fulfilment of EPR obligations and

(h) provision for verification, audit and monitoring of obligated entities.

ii. The Plastic Waste Management (Second Amendment) Rules, 2022, were notified on July 6, 2022. The amendment aligns the rules with the Guidelines on Extended Producer Responsibility for plastic packaging. The amendment provides a statutory framework for biodegradable plastics after conforming to BIS Standards and the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) certification. The rules mandate that environmental compensation shall be levied based upon the polluter pays principle, on persons not complying with the provisions of these rules, as per guidelines notified by the Central Pollution Control Board.

7.79 The waste management infrastructure in the States/UTs is also being strengthened through the Swachh Bharat Mission. All States/UTs have constituted a Special Task Force for eliminating single-use plastics and effectively implementing Plastic Waste Management Rules, 2016. A National Level Taskforce has been formed by the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change to make coordinated efforts to eliminate identified single-use plastic items and effective implementation of Plastic Waste.

7.80 The resumed session of the fifth United Nations Environment Assembly held in Nairobi on 2 March 2022 adopted a resolution “End plastic pollution: towards an international legally binding instrument”. India engaged constructively with all member states to develop a consensus on the resolution for driving global action on plastic pollution. On the insistence of India, the principle of national circumstances and capability17 while addressing plastic pollution was included in the resolution text to allow developing countries to follow their development trajectories.

Battery Waste Management

7.81 The Government published the Battery Waste Management Rules, 2022, on August 24, 2022 to ensure environmentally sound management of waste batteries. Notifying these rules is a transformative step towards promoting the circular economy. New rules will replace Batteries (Management and Handling) Rules, 2001. The rules cover all types of batteries, viz. Electric Vehicle batteries, portable batteries, automotive batteries, and industrial batteries.

7.82 The rules function based on the concept of Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), where the producers (including importers) of batteries are responsible for the collection and recycling/refurbishment of waste batteries and the use of recovered materials from wastes into new batteries. EPR mandates that all waste batteries be collected and sent for recycling/ refurbishment, prohibiting disposal in landfills and incineration. To meet the EPR obligations, producers may engage themselves or authorise any other entity to collect, recycle, or refurbish waste batteries.

E-waste Management

7.83 The Government notified the E-Waste (Management) Rules, 2022, on November 2, 2022. These rules will replace the E-waste (Management) Rules, 2016, and will be effective from April 1, 2023. These rules will launch a new Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) regime for e-waste recycling. The salient feature of new rules is as under:

- Applicable to every manufacturer, producer, refurbisher, dismantler, and recycler who must register with CPCB. No entity shall carry out any business without registration and not deal with any unregistered entity.

- The authorisation has now been replaced by registration through an online portal, and only manufacturers, producers, refurbishers and recyclers require registration.

- Schedule I has been expanded, and now 106 Electrical and Electronic Equipment (EEE) have been included under the EPR regime.

- Producers of notified EEE have been given annual E-Waste Recycling targets based on the generation from the previously sold EEE or based on sales of EEE, as the case may be.

- Management of solar PV modules /panels/ cells added in new rules.

- The recycled quantity will be computed based on end-products to avoid false claims.

- Provision for generation and transaction of EPR Certificate has been introduced.

- Provisions for environmental compensation and verification & audit have been introduced.

7.84 Under these rules, a provision for reducing hazardous substances in the manufacturing of EEE has been provided. It mandates that every producer of EEE and their components shall ensure that their products do not contain lead, mercury, and other hazardous substances beyond the maximum prescribed concentration. It also provides for recognition and registration, skill development, monitoring, and ensuring the safety and health of workers involved in dismantling and recycling e-waste.

Conclusion

7.85 India is spearheading one of the world’s most ambitious clean energy transitions and remains steadfast in its commitment to combating climate change. Despite the adverse impacts of Covid-19 on the economy, India has enhanced its climate ambition manifold and embarked on a long-term strategy towards a Low GHG Emission Development Strategy by adopting a multi-pronged approach.

7.86 The energy transition plan is complemented by numerous policies intended to improve the ecosystem to deploy promising technological innovations, like green hydrogen. The country has consistently modified/amended regulatory standards and adopted policy-level interventions to support the development and adoption of new technology. India’s progress on energy transition may be understood from the fact that it has enhanced its non-fossil fuel based installed capacity target to 50 per cent in its updated NDC as the target of 40 per cent of the first NDC was achieved well in advance.

7.87. The sustainable finance framework has also evolved from the initial steps covering the top listed 100 companies required to conform to sustainability standards. The requirement has now not only been extended to 1000 top listed companies on a mandatory basis but also the sustainability standards have become much stronger and measurable that correspond to the best practices while taking into account the specific context of India.

7.88 As mentioned earlier, resources have competing use, and development strategies are not substitutable. Modification in the development pathway has a transition cost, including social and economic costs. India’s climate ambitions require resources to be dedicated to the cause of climate change, in addition to, what is needed for the country’s development goals. Obligations on climate should be matched with the on-time availability of climate finance, technology, and inputs like critical minerals, while not jeopardising the socio-economic development objectives and aspirations.

7.89 Even if India has so far undertaken climate actions on its own, the heightened expectations of further large-scale climate measures have to be equated with the enhanced initiatives by developed countries in terms of providing means of implementation, including finance, technology transfer, and capacity-building support.

7.90 More importantly, the global climate agenda will advance if advanced countries can set examples of policy and behavioural changes that work in their backyard and whose trade-offs are well recognised and accepted by their people. Then, it might be realistic to expect such policies and behavioural expectations of households to succeed in developing countries with suitable adaptation.

******

Note:-

1 World Economic Outlook, October 2021, Ch.1 World Economic Outlook, October 2021: Recovery During A Pandemic (imf.org)

2 Thomas C. Schelling (1992): ‘Some economics of global warming’, American Economic Review, March 1992 Some Economics of Global Warming on JSTOR

3 ‘Germany Revives Coal as Energy Security Trumps Climate Goals’, Bloomberg, 22 December 2022 (https://www.bloomberg.com/news/ articles/2022-12-22/germany-returns-to-coal-as-energy-security-trumps-climate-goals)

4 ‘Fighting Climate Change: International Attitudes Toward Climate Policies’, NBER Working Paper No. 30265, September 2022 (https:// www.nber.org/papers/w30265) 220 Economic Survey 2022-23

5 ‘The new-style energy crisis’, Daniel Yergin interviewed by Project Syndicate, July 2022 (https://www.project-syndicate.org/onpoint/new-style-energy-crisis-by-daniel-yergin-2022-07)

6 Daniel Yergin (2022): ‘Bumps in the Energy Transition’, Finance & Development, International Monetary Fund, December 2022 (https:// www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2022/12/bumps-in-the-energy-transition-yergin)

8 Pujarini Samal, Jyoti Srivastava, S.R. Singarasubramanian, Pooja Nitin Saraf, Bipin Charles, Ensemble modeling approach to predict the past and future climate suitability for two mangrove species along the coastal wetlands of peninsular India, Ecological Informatics, Volum722022.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2022.101819.

9 ‘Harnessing Green Hydrogen – Opportunities for Deep Decarbonisation in India’, published in June 2022 by NITI Aayog. https://www.niti. gov.in/sites/default/files/202206/Harnessing_Green_Hydrogen_V21_DIGITAL_29062022.pdf

10 International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) (2020) Green hydrogen cost reduction: Scaling up electrolysers to meet the 1.50C Climate Goal. Green hydrogen cost reduction (irena.org)

11 LCOH refers to the cost of hydrogen production per unit of hydrogen includind capital and operational costs.

12 International Energy Agency Report on ‘The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions’. The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions – Analysis – IEA

13 Beloskar, V. D., & Rao, S. V. D. (2022). Did ESG Save the Day? Evidence from India During the Covid-19 Crisis. Asia-Pacific Financial Markets, 1-35.

14 Mulchandani, K., Mulchandani, K., Iyer, G., & Lonare, A. (2022). Do Equity Investors Care about Environment, Social and Governance (ESG) Disclosure Performance? Evidence from India. Global Business Review, 23(6), 1336-1352

15 The TX2 Tiger Conservation Award is given away by Conservation Assured | Tiger Standards (CA|TS), Fauna & Flora International, Global Tiger Forum, IUCN Integrated Tiger Habitat Conservation Programme, Panthera, UNDP Lion’s Share, Wildlife Conservation Society, and World Wide Fund For Nature’s (WWF’s) Tigers Alive Initiative.

16 CITES is an international agreement between governments to ensure that international trade in specimens of wild animals and plants does not threaten the survival of the species.

17 It was essential as not all countries are equally placed in terms of development and capabilities..

The cumulative emission of 4% of the world’s total still puts India in 7th place, isn’t it? 🙂 Very detailed article.