Preliminary findings of assessment of orders of the Central Information Commission (CIC)

By Satark Nagrik Sangathan (SNS) & Centre for Equity Studies- October, 2018

Preliminary findings of research undertaken by SNS & CES1

Page Contents

I. Introduction

The Right to Information (RTI) Act has undoubtedly been one of the most empowering legislations for the citizens of India. It has been used extensively by people on a range of issues – from holding the government accountable for delivery of basic rights and entitlements to questioning the highest offices of the country. The law has initiated the vital task of redistributing power in a democratic framework. Estimates suggest that every year 40 to 60 lakh2 RTI applications are filed in India.

Under the RTI Act, information commissions (ICs) are mandated to safeguard and facilitate people’s fundamental right to information. Consequently, ICs are widely seen as being critical to the RTI regime. The experience in India, also captured in various national studies on the implementation of the RTI Act undertaken by SNS, RAAG and CES in collaboration with various groups including the National Campaign for Peoples’ Right to Information in 2008, 2014, 2017 and 2018 has been that the functioning of information commissions is a major bottleneck in the effective implementation of the RTI Act3. In addition to problems like huge backlogs of cases in commissions, the quality of orders of ICs has also been a cause of concern.

This report discusses the preliminary findings of research undertaken by Satark Nagrik Sangathan (SNS) & Centre for Equity Studies (CES) on the orders of the Central Information Commission (CIC). The findings discussed in this report are part of a forthcoming assessment which, in addition to the orders of the CIC, will also discuss significant recent judgments of the Supreme Court and High Courts.

II. Methodology

The findings discussed here are based on an analysis of orders of Central Information Commission.

549 orders of the Central Information Commission, for the period January 1, 2018 to March 31, 20184, were randomly sampled and analysed for the purpose of the study.

All orders were analysed in terms of their completeness and compliance with the provisions of the law. Where disclosure of information in appeals was party or fully denied, the section of the law/reasons relied on for denial was recorded and it was examined whether the denial of information was in keeping with the provisions of the RTI Act and whether the orders were well reasoned. In addition, it was assessed whether violations of the law were acted against as per the provisions of the RTI Act.

III. Key Findings

1. Quality of orders

The Supreme Court (SC), in numerous orders, has cautioned against the tendency of adjudicators to give cryptic, unreasoned orders. In 2012, the SC in Manohar s/o Manikrao Anchule vs. State of Maharashtra (Civil Appeal No. 9095 of 2012), categorically, and in great detail, laid down that judicial, quasi-judicial, and even administrative orders must contain detailed reasoning for their decisions.

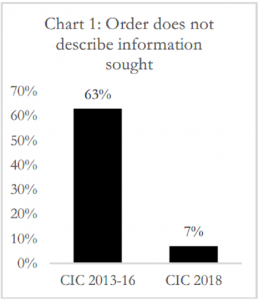

The assessment found that 7% of the orders analysed contained deficiencies in terms of not recording critical facts like information sought by the appellant/complainant. This is a significant improvement – a prior assessment of orders of the CIC from 2013 to 2016 had found that 63% of orders did not describe the information sought5 (see Chart 1). In fact, the previous assessment had highlighted that many of the orders comprised just 2-3 lines, recording only the decision of the IC, without any reference to the background or the relevant facts of the case like dates, details of information sought, decision of PIO/ FAA and the grounds for the decision of the IC and the basis thereof.

While the performance of the CIC has greatly improved in terms of recording critical facts like dates, details of information sought etc., in several cases where information was denied, it was found that the orders were not adequately reasoned and could be said to be non-speaking orders6. Several such orders merely summarise the contention of the information seeker and the denial by the PIO and conclude by stating that intervention of the Commission was not required, without explaining why the particular exemption was valid in the case and without weighing the necessary exceptions to the exemptions in the RTI Act7.

The phenomenon of ICs not passing speaking orders is problematic for several reasons. First, information seekers, the concerned public authorities, and the public at large, have no way of finding out the rationale for the decisions of ICs. People have a right to know not just the decision, but also the basis of the decision. In fact, even the RTI Act makes it obligatory for a public authority under section 4(1)(d) of the Act, to proactively “provide reasons for its administrative or quasi-judicial decisions to affected persons”. In the case of an IC order, whereas information seekers and concerned public authorities are no doubt “affected persons”, even the general public is an affected party, as often decisions have far reaching consequences on the publics’ right to access information. Therefore, passing a non-speaking order, which only records the decision of the IC, but does not provide the reasons for its decisions or other relevant details, is a violation of peoples’ right to information and goes against the fundamental principles of transparency.

Second, orders of ICs are often challenged before courts. The tests of legality, fairness and reasonableness become exponentially more difficult to pass when the orders don’t speak for themselves and lack essential information, facts and reasoning. This is especially problematic as information commissions are often not made a party in legal challenges to their orders before the court (there are differing legal opinions on this matter), and therefore they have no opportunity to present any material in defence of their directions, which is not contained in the original order. As IC orders are supposed to be self-contained, it is unlikely that any records would exist with the commission that could be presented before the court to explain the reasoning behind cryptic orders. Reasons provided after the order, whether verbally or on the basis of additional documents, would in any case not be considered part of the original order which was under challenge. Deficiencies in IC orders also burden the information seekers with the task of defending orders of the ICs before courts. Vague use of language, insufficient or incorrect recording of facts and not recording basis of orders, weigh in in favour of the petitioner assailing the order of the commission.

Third, deficient orders prevent effective public scrutiny and accountability of the institution of information commissions and the performance of information commissioners.

Finally, deficient orders have little value in terms of furthering the cause of transparency outside the scope of the limited order. Rather than the decision itself, it is the enunciation of reasons, logic and basis of the decision which create public awareness and lead to public debates about enhancing the scope of transparency and accountability in the country.

2. Backlogs in Information Commissions

The legal maxim “Justice delayed is justice denied” is perhaps most pertinent for the RTI Act today. The assessment found that on average the CIC takes 319 days to hear and give an order on an appeal/complaint from the date that it was filed before the commission.

The assessment found that there is wide variation in the time taken to hear a matter. Time taken ranged from disposal within 36 days of case being filed to 862 days or nearly two and a half years. Assuming that cases are disposed chronologically, the reason for the large variation in the disposal time is not clear. The specific orders in which the appeal/complaint was disposed inordinately quickly, did not record any circumstances which would warrant the specific case being taken ahead of others.

The issue of huge backlogs and subsequent long waiting time for disposal of appeals and complaints has been consistently highlighted in previous national assessments. The assessment published in 2018 had also found that the estimated time required for disposal of an appeal/complaint by the CIC was 10 months8. This was arrived at using the backlog of appeals/complaints in ICs and their monthly rate of disposal of cases.

The huge backlog in the disposal of appeals and complaints by the commissions and the concomitant long waiting time for disposal of appeals and complaints is one of the most serious problems being faced by the transparency regime in India. This is especially problematic for marginalized sections of the Indian population who use the RTI law to try and access information about their basic entitlements like subsidized rations, old age pensions, medical facilities in hospitals and minimum wages. It is a daunting task for them to approach the information commission in case of denial of requisite information. If there are inordinate delays in the commissions, the law becomes meaningless for them in terms of ensuring their right to information.

The analysis of orders showed that long waits in the disposal of cases also resulted in PIOs who had violated the Act, not being penalised as the IC recorded that the PIO had since retired and a penalty could not be levied9.

Often the huge pendency and the concomitant long waiting time are a result on non-appointment of commissioners in the IC. Even though, as of October 2018, nearly 25,000 appeals/complaints are pending in the CIC, since January 1, 2018 the CIC has been functioning with only 7 commissioners. Four more commissioners, including the Chief Information Commissioner of the CIC are set to retire by December 1, 2018, which will reduce the strength of the commission to just three commissioners.

The Central Information Commission, in March 2011, stipulated a norm that each single bench of the Commission will endeavour to dispose 3200 appeals/complaints per year10. A comparison of the stipulated norm and the actual disposal between January 1, 2018 to March 31, 2018, shows that most commissioners exceeded the norm (see chart 2). If 3,200 appeals/complaints are to be disposed each year by a commissioner, it implies that each commissioner should dispose 800 appeals/complaints in a three month period.

| Chart 2: Commissioner-wise number of appeals/complaints

January 2018 to March |

disposed between 2018 |

| Mr. R. K. Mathur | 1,222 |

| Mr. Yashovardhan Azad | 1,561 |

| Prof. M. Sridhar Acharyulu | 952 |

| Mr. Sudhir Bhargava | 994 |

| Mr. Bimal Julka | 778 |

| Mr. Divya Prakash Sinha | 532 |

| Mr. Amitava Bhattacharyya | 756 |

| Does not include Ms. Manjula Prasher as she retired in Jan ’18. | |

3. Penalty imposition

The RTI Act empowers the ICs to impose penalties of upto Rs. 25,000 on erring PIOs for violations of the RTI Act. The penalty clause is one of the key provisions in terms of giving the law its teeth and acting as a deterrent for PIOs against violating the law. Despite Section 20 of the RTI Act clearly defining the violations of the law for which PIOs must be penalised, the study found that ICs imposed penalty in only an extremely small fraction of the cases in which penalty was imposable.

Across the sample, an average of 56% orders recorded one or more violations listed in Section 20 of the RTI Act, based on which the IC should have triggered the process of penalty imposition. Of these 56% cases, only in 28% cases ICs issued notices to the PIOs asking them to show cause why penalty should not be levied. After show cause notices were issued, the subsequent order recording the final directions of the IC in terms of whether or not penalty was imposed, could only be found for 72% of the cases in which show cause notices were issued. Finally, penalty was imposed in only 4% of the cases in which it was potentially imposable.

The commissioner-wise break up of show cause notices as percentage of the total such notices issued and penalty imposed as a percentage of the total penalty imposed, in the sample, is available in chart 3.

| Chart 3: Commissioner-wise percentage of Show Cause Notices issued and penalty imposed as per the sample |

||

| Show Cause Notices issued (as % of total) | Penalty imposed (as % of total) |

|

| Mr. R. K. Mathur | 9% | 0% |

| Mr. Yashovardhan Azad | 11% | 11% |

| Prof. M. Sridhar Acharyulu | 45% | 76% |

| Mr. Sudhir Bhargava | 10% | 0% |

| Mr. Bimal Julka | 5% | 0% |

| Mr. Divya Prakash Sinha | 0% | 0% |

| Mr. Amitava Bhattacharyya | 20% | 13% |

The non-imposition of penalty has many serious implications as it sends a message that violations of the law will not invite any adverse consequences. This destroys the basic framework of incentives and disincentives built into the RTI law and promotes a culture of impunity.

In terms of amount of potential penalty foregone by ICs, the analysis of 549 orders showed that by foregoing penalties in cases where it was potentially imposable, ICs caused a potential loss of more than Rs. 55.7 lakh. Extrapolating this nationally 11, an estimated loss of Rs. 203 crores is being caused annually by ICs not imposing penalties.

But, even more important than the revenue lost is the loss of deterrence value that the threat of penalty was supposed to have provided. This has resulted in PIOs denying information, delaying information, not responding at all, or violating other provisions of the RTI Act with impunity, without fear of consequences.

The non-imposition of penalties is perhaps the most vexatious of issues relating to the proper enforcement of the RTI Act. The provision of penalty as prescribed in section 20(1) of the RTI Act is to be triggered if a PIO violates the RTI Act in any one or more of the following ways:

i. without any reasonable cause refuses to receive an application

ii. without any reasonable cause delays furnishing information

iii. with mala fide denies the request for information

iv. knowingly gives incorrect information

v. knowingly gives incomplete information

vi. knowingly gives misleading information

vii. destroys information which was the subject of any request

viii. obstructs in any manner the furnishing of information

In several cases it was found that the IC did not issue a show cause notice or dropped penalty proceedings despite there being a delay in disclosure of information as the IC held that there was no malafide on the part of the PIO. This is extremely problematic as malafide has to be proven only in cases of denial of information and not in cases of delay. The laxity in imposing penalties is also allowing PIOs to take liberties with the RTI Act at the cost of the public.

4. IC orders in violation of the RTI Act

The assessment found that there is a growing tendency among adjudicators to exempt information from disclosure citing grounds which are not provided for in the RTI Act. From among the appeals where part or full information was denied, more than 60% denials were in violation of the RTI Act, i.e. the IC denied information on grounds which are not provided for in the RTI Act.

The assessment found that in several cases information is denied without citing any specific exemption under the RTI Act. . In some cases, ICs were found to uphold denial of information on the premise that information related to a third party or that the third party had not consented to the disclosure of information. This, despite the fact that Section 11 does not allow for ‘veto’ power to the third party and clarifies that the decision regarding disclosure is to be finally made by the PIO while keeping in view the submission of the third party. In fact, the provision is worded in such a manner that the third party rights would be invoked only if the PIO had decided to disclose the information, i.e. reached a conclusion that the information was not exempt under the RTI Act. In order to prevent disclosure, the third party would have to make a case for how the information was indeed exempt under Section 8 or 9. And even if it succeeded in proving the same, the PIO would still be obligated to consider if public interest in the disclosure of information would outweigh any possible harm or injury to the interests of such third party.

Further in cases where part of a record would qualify for exemption under section 8 of the RTI Act, instead of invoking section 10 to sever the exempt portion, in many cases, access to the whole record was found to be denied.

5. Who is using the RTI Act & for what?

As part of the assessment, the gender ratio of appellants/complainants was analysed’2.

The assessment found that 91% of the appeals/complaints were filed by men and 9% by women. This broadly reflects the gender divide in terms of filing RTI applications. A previous assessment’3, on the basis of analysis of a random sample of RTI applications, had found that 92% of RTI applicants were male and only 8% female.

All orders in the assessment were analysed to see whether information sought in the RTI application was such that it should have been proactively disclosed.

Alarmingly, the assessment of the sample orders found that 44% of RTI applications sought information where, atleast a part of the information if not all, was such that it should have been made public proactively, without anyone applying for it. This included information that should have been made proactively available under Section 4 of the RTI Act and information which even without the existence of the RTI Act should have been proactively provided (for instance, action taken on a complaint). Despite the large scale violation of provisions of proactive disclosures, the ICs in most such orders did not give directions requiring compliance with provisions mandating proactive disclosures.

The lack of compliance with provisions of mandatory proactive disclosures results in adjudicators spending a significant amount of their time on hearing appeals and complaints of

people seeking information which in any case should have been proactively disclosed.

Notes:-

1 For further information, please contact Anjali Bhardwaj (9910009819), Amrita Johri (9810273984), email satarknagriksangathan@gmail.com website: www.snsindia.org

2 ‘Peoples’ Monitoring of the RTI Regime in India: 2011-2013’ by RaaG & CES, 2014

3 ‘Safeguarding the Right To Information’, RaaG & NCPRI, 2009; ‘Peoples’ Monitoring of the RTI Regime in India: 2011-13’, RaaG & CES 2014 (http://x.co/raagces); & ‘Tilting the Balance of Power – Adjudicating the RTI Act’, RaaG, SNS & Rajpal, 2017, (http://snsindia.org/Adjudicators.pdf); ‘Report Card of Information Commissions in India’, SNS & CES, 2018 (www.snsindia.org/IC2018.pdf)

4 Upon retrieving orders by date (‘Decision From’, ‘Decision To’ fields), the CIC website picks up the date on which the order was uploaded and not the date of the order itself.

5 Chapter 5, ‘Tilting the Balance of Power – Adjudicating the RTI Act’, RaaG, SNS & Rajpal, 2017, (htpt://snsindia.org/Adjudicators.pdf);

6 A detailed discussion of such orders will be part of the forthcoming report

7 In every case of denial of information under Section 8 of the RTI Act, the IC must weigh whether there is larger public interest in the matter warranting disclosure (Section 8(2)) or whether information is such that it cannot be denied to Parliament or Legislature and hence cannot be denied to a person (proviso to section 8(1)) or the information pertains to matters which occurred twenty years ago and hence most of the exemptions are no longer applicable (Section 8(3)).

8 ‘Report Card of Information Commissions in India’, SNS & CES, 2018 (www.snsindia.org/IC2018.pdf)

9 A discussion on whether this approach is in keeping with the law will be part of the forthcoming report.

10 https://cic.gov.in/sites/default/files/Circulars%20%26Noification/Minutes22032011.pdf

11 As per assessments of 2014, 2017 & 2018 annually ICs across India dispose an estimated 2 lakh appeals & complaints.

Since for 549 cases disposed, potential loss of Rs 55.7 lakh was caused, hence loss in 2 lakh cases can be estimated to be Rs. 203 crore.

12 Gender was determined on the basis of the name and title written in the order of the sample. Whereas names are not always accurate indicators of the gender of a person, it was assumed that there would be as many men as women with gender neutral names, thereby balancing out the errors.

13 ‘Peoples’ Monitoring of the RTI Regime in India: 2011-2013’ by RaaG & CES, 2014