REPORT OF THE INSOLVENCY LAW COMMITTEE – MAY, 2022

Ministry of Corporate Affairs

Government of India

New Delhi, the 20th May, 2022

To,

The Honourable Union Minister of Finance and Corporate Affairs

Madam,

We have the privilege and honour to present this 5th report of the Insolvency Law Committee, set up on 16th November, 2017 (reconstituted on 6th March, 2019 as Standing Committee) to make recommendations to the Government on issues arising in implementation of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016, as well as on the recommendations received from various stakeholders.

2. The Committee has tried to take a comprehensive view while suggesting changes in the Code keeping in mind difficulties being faced by different stakeholders. It has endeavoured to improve the efficiency of the corporate insolvency resolution, liquidation (including voluntary liquidation process) keeping in mind to further the objective of “the time bound reorganization and insolvency resolution” and “maximization of value of assets” of the Code.

3. We thank you for providing us an opportunity to present our views on the issues arising from implementation of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 and related matters.

Yours Sincerely,

(Rajesh Verma)

Chairman

PREFACE

The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (IBC/Code) has proven to be a transformational economic legislation in a short span of five years since its enactment. The Code has been tested time and again, and jurisprudence has evolved settling many issues faced during its implementation. Together with this, timely interventions by the Government have enabled the development of a robust insolvency resolution framework in India. It has been a constant endeavour of the Insolvency Law Committee (ILC/Committee), constituted by the Ministry of Corporate Affairs (MCA), to monitor the progress and implementation of the Code, consider issues raised by various stakeholders, identify gaps and bottlenecks, and recommend corrective measures for optimal functioning of the Code. Soon after making recommendations for the pre-packaged insolvency resolution framework for MSME corporate debtors, for which amendments to the Code, through an Ordinance, were made in April 2021, the Committee focused on further strengthening and streamlining the processes under the Code.

The ILC is submitting its 5th Report which provides recommendations in respect of the corporate insolvency resolution (CIRP) and liquidation processes. The issues taken up in this report are based on a review of stakeholder suggestions, raised in stakeholder consultations conducted by the MCA and the IBBI or sent as public comments to the MCA. The key recommendations in this Report are as follows:

(i) Mandating reliance on information utilities (IUs) for establishing default: With the development of IU infrastructure, the availability and acceptability of IU data has increased. Reliance on IU records has the potential of expediting the process of proving default, and may thus, avoid delays in admission of CIRP applications. Therefore, the Committee has recommended that certain financial creditors should be mandated to submit IU records with their CIRP application. The Adjudicating Authority (AA) should not seek any other documentation for proving default when IU records are submitted by the applicant. A similar mandate may be extended to operational creditors in due course of time.

(ii) Continuation of proceedings for avoidable transactions and improper trading after CIRP: It has been observed that there is lack of clarity on whether proceedings for avoidable transactions and improper trading can continue after the completion of a CIRP. The Committee discussed that continuation of such proceedings is permitted by Section 26 of the Code and has recommended that a clarificatory amendment may be made to this provision to avoid any doubts in this regard. Further, suitable amendments may be made to the Code to ensure that the resolution plan provides sufficient clarity for the smooth conduct of proceedings for avoidable transactions or improper trading. This will ensure that there is clarity amongst stakeholders on the manner in which such proceedings will continue after the approval of the resolution plan.

(iii) Change in threshold date for look-back period: The threshold date for the look-back period of avoidable transactions should be altered to cast a wider net for catching such transactions. Consequently, the threshold date should be changed to the date of the filing of application for initiation of CIRP instead of the date of commencement. Further, transactions from the date of filing until the date of commencement should also be included in the look-back period. This will not only help increase the scope of avoidable transactions but will also discourage any perverse incentives for corporate debtors to delay the admission of CIRP applications.

(iv) Curbing submission of unsolicited resolution plans and revisions of resolution plans: It has been observed that there are divergent practices regarding the timeline and manner of submission of resolution plans. Although there are stage-wise timelines provided in the regulations, resolution plans are received by the resolution professional after the stipulated deadlines. In some cases, revisions are made to submitted resolution plans in an attempt to outbid other potential resolution applicants. Such practices lead to divergent practices leading to inconsistencies, delays, and lack of procedural sanctity. Therefore, the Committee has recommended that a mechanism for reviewing late submissions of plans and unsolicited revisions to plans should be laid down in the regulations. Pursuant to the recommendations of the Committee in this regard, some amendments have already been carried out in the CIRP regulations.

(v) Timeline for approval or rejection of resolution plan: Delays have been observed in the disposal of resolutions plans submitted to the AA. Such delays are often caused due to a high number of objections to the proposed resolution plan, or due to a high degree of pendency of cases. Nevertheless, delays at the stage of disposal of the resolution plan are value destructive and discourage prospective resolution applicants from submitting plans. Therefore, the Committee has recommended that AA should dispose the resolution plan within 30 days of receiving it. The AA should record reasons in writing if it fails to dispose the plan within this timeline.

(vi) Standard of conduct of the Committee of Creditors (CoC): The CoC has been entrusted with wide powers under the Code. It is tasked with making key decisions during the CIRP, including the manner of resolving the corporate debtor’s distress. Thus, improper conduct by members of the CoC impacts the life of the corporate debtor, and consequently its stakeholders. Given this pivotal role of the CoC, the Committee has recommended that the IBBI should issue guidelines that provide the standard of conduct for members of the CoC. This may be in the form of guidance that provides a normative framework to members of the CoC about the manner of conducting themselves in processes under the Code.

(vii) Stakeholders Consultation Committee (SCC): The SCC may play a pivotal role in the liquidation process by giving valuable commercial insights and maintaining oversight over the functioning of the liquidator. Therefore, the Committee has recommended that the liquidator must mandatorily consult the SCC. Accordingly, Section 35(2) of the Code and regulations made thereunder may be suitably amended. Pursuant to the recommendations of the Committee, amendments requiring such mandatory consultation with the SCC have already been made in the regulations.

(viii) Secured Creditor’s Contribution: Secured creditors are permitted to step out of the liquidation process by choosing to realise their security interest outside instead of relinquishing it. The Code provides that secured creditors opting to realise their security interest outside the liquidation process are liable to contribute towards CIRP costs. The Committee has recommended that such secured creditors should also be required to contribute towards workmen’s dues in the same manner as they would have if they had relinquished their security interest. Workmen are key stakeholders of the corporate debtor and form the backbone of efforts to preserve the business of the corporate debtor, both before and during insolvency proceedings. Thus, contributions made by secured creditors towards their dues should be explicitly provided in the Code by amending Section 52. Further, when a secured creditor steps outside the liquidation process, he should also be liable to pay the liquidator for any expenses incurred by him for the preservation and protection of its security interest. If a secured creditor fails to make the required contributions, its security interest should be deemed to have been relinquished and become part of the liquidation estate.

(ix) Voluntary Liquidation Process: There are varying practices on whether, and on what basis, a voluntary liquidation process can be terminated before the passing of a dissolution order. The Committee has recommended that such termination should be permitted since the process is meant for solvent entities whose business prospects may have changed since the commencement of the process. The Committee has recommended a simple mechanism for terminating a voluntary liquidation process which is akin to the mechanism for commencement of the process. Suitable amendments should be made to the Code to lay down this mechanism so as to ensure that there is consistent practice on termination of voluntary liquidation processes.

(x) Operationalizing the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Fund (IBC Fund): Section 224 may be suitably amended to empower the Central Government to prescribe a detailed framework for contributions to and utilisation of the IBC Fund.

(xi) Additional Changes: There should be an appellate mechanism for orders issued under section 220 by the IBBI and its disciplinary committee. Such appeals may be filed with the NCLAT. Further, to have a more comprehensive and optimal framework for rules and regulations, Sections 239(1) and 240(1) may be amended to provide that the rules and regulations may be made for carrying out the “purposes” of the Code.

The recommendations of the Committee will further strengthen the insolvency and bankruptcy framework in India by providing clarity and improving processes under the Code. I am confident that these recommendations will go a long way in achieving the objectives of the Code. The Committee will monitor further developments and keep striving to enhance the effectiveness of the Indian insolvency framework.

Rajesh Verma

Secretary, Ministry of Corporate Affairs &

Chairman, Insolvency Law Committee

New Delhi, 20th May, 2022

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Insolvency Law Committee takes this opportunity to submit the 5th Report after deliberations on various issues to streamline the corporate insolvency resolution and, liquidation including voluntary liquidation processes to further the objectives of the Code. The Committee would like to thank the industry chambers, professional institutes, law firms, academicians and other experts who made valuable suggestions for review of the Code.

The Committee expresses its gratitude to the members of Insolvency Law Committee, for their valuable contribution in the review process, and for their participation in, deliberations including with respect to enabling swifter admission and approval of resolution plan; streamlining the avoidance transactions and allowing termination of voluntary liquidation process, etc.

The Committee acknowledges the research and drafting support provided by the team from Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy comprising of Ms. Aishwarya Satija, Mr. Akash Chandra Jauhari, Ms. Manmayi Sharma, Ms. Devashri Mishra, and Ms. Anjali Ayachil.

The Committee is grateful to Ministry of Corporate Affairs for providing logistical support and would like to make a special mention of the dedicated efforts put in by the team of officers of the Insolvency Division at the MCA comprising of Dr. Anuradha Guru, Economic Adviser, Mr. Satyajit Roul, Joint Director, Mr. Rajan Jain, Deputy Secretary, Mr. Saurabh Gautam, Deputy Director, Ms. Sunidhi Misra, Assistant Director, Mr. Sourav Sardar, Assistant Manager and Ms. Parul Chutani, Research Associate for collating suggestions, facilitating discussions and providing administrative and technical support for the functioning of the Committee.

**************************

LIST OF DEFINED TERMS

| BLRC | Report of the Bankruptcy Law Reforms Committee, Volume I, 2015 |

| CA, 1956 | Companies Act, 1956 |

| CA, 2013 | Companies Act, 2013 |

| CERSAI | Central Registry of Securitisation Asset Reconstruction and Security Interest of India |

| CIRP | Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process |

| CIRP Regulations | Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (Insolvency Resolution Process for Corporate Persons) Regulations, 2016 |

| CoC | Committee/s of Creditors |

| Code/ IBC | Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 |

| Committee | The Insolvency Law Committee |

| CPC | Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 |

| EoI | Expression of Interest |

| IBBI | Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India |

| IPA | Insolvency Professional Agency |

| IU | Information Utility |

| Rs. | Rupees |

| Liquidation Process Regulations | Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (Liquidation Process) Regulations, 2016 |

| LLP | Limited Liability Partnership |

| MCA | Ministry of Corporate Affairs |

| MSMEs | Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises |

| NCLAT | National Company Law Appellate Tribunal |

| NCLT | National Company Law Tribunal |

| NeSL | National e-Governance Service Limited |

| RBI | Reserve Bank of India |

| Report | Report of the Committee |

| RFRP | Request for Resolution Plan |

| RoC | Registrar of Companies |

| SCC | Stakeholders Consultation Committee |

| SEBI | Securities and Exchange Board of India |

| Report of the Standing Committee on Finance | Report of the Standing Committee on Finance on the Implementation of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (August 2021) |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| US | United States of America |

| VLP | Voluntary Liquidation Process |

| 2020 Report | Report of the Insolvency Law Committee, February 2020 |

CHAPTER 1 – BACKGROUND

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. The Code was enacted in May, 2016 to consolidate the laws relating to reorganisation and insolvency resolution in India and to ensure a time-bound resolution of insolvency, resulting in maximisation of value of the assets available for stakeholders, promotion of entrepreneurship, ensuring greater availability of credit and balancing the interests of all stakeholders concerned. The provisions relating to insolvency and liquidation of corporate persons came into force in December, 2016, while those relating to insolvency resolution and bankruptcy of personal guarantors to corporate debtors came into effect in December, 2019.

1.2. Within one year of implementation of the provisions of the Code relating to corporate insolvency, the Government constituted the Insolvency Law Committee to take stock of the functioning of the newly enacted Code and to make suitable recommendations to ensure its effective implementation. Thereafter, the Committee was re-constituted as a Standing Committee by an office order issued by the MCA on March 6, 2019.

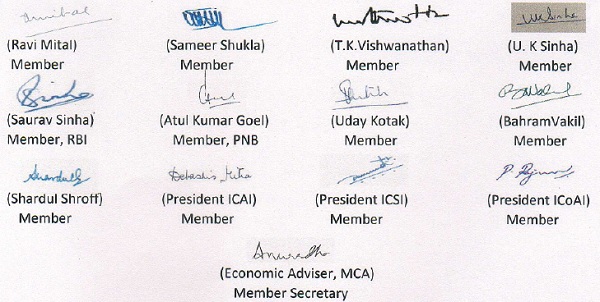

1.3. The Committee is chaired by Secretary, Ministry of Corporate Affairs, and members include Chairperson, IBBI; Additional Secretary (Banking), Department of Financial Services; Sh. T. K. Vishwanathan, Former Secretary General of the Lok Sabha and Chairman of the BLRC; Sh. U.K. Sinha, Ex SEBI Chairman; Nominee of the RBI, MD & CEO, Punjab National Bank; Sh. Uday Kotak, MD and CEO, Kotak Mahindra Bank; Sh. Shardul Shroff, Executive Chairman, Shardul Amarchand Mangaldas & Co.; Sh. Bahram Vakil, Partner, AZB & Partners; President, Institute of Chartered Accountants of India; President, Institute of Cost Accountants of India; President, Institute of Company Secretaries of India; and Economic Adviser, MCA (as Member Secretary). The Order of re-constitution of the Committee, along with a list of its members, has been provided in Annexure I.

1.4. The Committee has played a pivotal role in ensuring that the insolvency framework under the Code could readily address several implementation-based challenges as well as continually be updated in line with changing market realities. In the five years since its implementation, the Code has successfully overhauled the corporate insolvency and liquidation framework in India, helped plug information asymmetries and is appreciated as a key economic reform that has instilled a significantly increased sense of fiscal and credit discipline.

1.5. With the advent of the Covid-19 pandemic and the consequent lockdowns and disruption of economic activity, there were concerns world over that there would be a spate of insolvencies of businesses whose operations were affected by the pandemic. In response, the President of India on June 5, 2020 promulgated the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (Amendment) Ordinance, 2020, which was replaced by the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (Second Amendment) Act, 2020, that inter alia, suspended the operation of provisions for initiation of CIRP for a period of one year, in order to help prevent corporations whose business operations were affected by the pandemic, from being pushed into insolvency.

1.6. The continued evaluation of the Code by the Committee, and its considered suggestions based on issues highlighted by stakeholder comments and implementation experience, has ensured that the Code has been amended in quick response to emerging issues and in line with changing market realities. Thereafter, in light of the need for a hybrid and alternative insolvency framework for pandemic-affected MSMEs that did not have access to the Code during its suspension, the Committee also gave its recommendations on the design for a pre-packaged insolvency resolution framework as a quick and affordable alternative insolvency resolution mechanism, through its report in July 2021. Based on the suggestions of the Committee, the pre-packaged insolvency resolution process was introduced to the Code as a separate chapter through the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (Amendment) Ordinance on April 4, 2021, which was then replaced by the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (Amendment) Act, 2021 on August 12, 2021.

1.7. Alongside its deliberations and meetings on the pre-packaged insolvency resolution framework, the Committee also looked at issues concerning the CIRP and liquidation process of corporations under the Code. These were deliberated keeping in mind the dynamic nature of these issues and the need for revisiting and resolving certain long-standing issues in the implementation of the Code. The Committee was taken through numerous suggestions and comments provided by stakeholders including issues concerning the admission process and the scope of the moratorium for CIRP; existing and emergent issues concerning avoidance actions and improper trading, as well as those relating to submission of the resolution plan and liquidation of the corporate debtor.

1.8. The need for a re-look at these issues concerning the implementation of the CIRP and liquidation processes under the Code also comes at a crucial time – not only has the suspension on CIRP filings been lifted, making the Code open to new insolvency filings, but the Code has also completed five years since its enactment. Over these five years, the Code has solidified its image as a game changing legislation in the field of insolvency resolution. Its implementation has continually strived to achieve the core tenets of time-bound insolvency resolution, value maximisation and of balancing the interests of all stakeholders. Keeping these principles in mind, the Committee has once again made recommendations to ensure effective implementation of the CIRP and liquidation frameworks, and continued access and ease of doing business for corporate entities in India.

II. WORKING PROCESS

1.9. The Committee had its first meeting on February 10, 2021 and its second meeting on February 13, 2021. Another meeting of the Committee took place on April 22, 2022.

1.10. The MCA had invited comments from the public through an online facility available on the websites of the MCA and the IBBI during the period between December 23, 2021 to January 13, 2022. During its deliberations, the Committee considered the suggestions received in the public comments and through the stakeholder consultations conducted by the MCA.

1.11. The MCA engaged the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy to assist the Committee by providing research on the relevant legal principles and international jurisprudence, and to assist the Committee in drafting this Report.

III. STRUCTURE OF THE REPORT

1.12. This Report details the deliberations and recommendations of the Committee in assessing the implementation of the Code. The recommendations address the issues highlighted by the public and stakeholders concerning the CIRP and liquidation processes and avoidance actions and improper trading. The recommendations in this Report review the existing practice and implementation of the Code, having due regard to any related domestic legislation and international insolvency frameworks, and suggest whether there is need for amendment to the provisions of the Code and to its relevant subordinate legislation.

1.13. The Report also contains two annexures: Annexure I, which is the Order of re-constitution of the Committee dated March 6, 2019 and Annexure II, which is a summary of the recommendations made by the Committee.

CHAPTER 2 – RECOMMENDATIONS PROPOSING AMENDMENTS TO THE CODE AND RELEVANT SUBORDINATE LEGISLATION

I. MANDATING RELIANCE ON IUS FOR CERTAIN FINANCIAL CREDITORS

2.1. The NCLT, which is the Adjudicating Authority for corporate persons under the Code, is required to admit an application for initiation of a CIRP within fourteen days of receiving it.1 It is now a settled position of law that this fourteen-day time-period is directory in nature.2 Consequently, the Adjudicating Authority is not barred from admitting or rejecting an application after the requisite time-period. In practice, the admission or rejection of most CIRP applications takes a considerably longer time than fourteen days.3 Stakeholders have voiced concerns about such delays and backlog of cases pending admission.

2.2. The Committee noted that in the past, measures have continually been taken to help further speedy admission of CIRP. For instance, the Code was amended in 20194 to provide that the Adjudicating Authority shall be required to provide reasons in writing for delay in admission of applications filed by financial creditors. Efforts are also consistently underway to create additional NCLT benches and to fill vacancies.5

2.3. Nevertheless, delays at the admission stage remain a critical issue in the implementation of CIRP. At the outset, the Committee took note of the importance of timelines under the Code. Jurisprudence on CIRP has clarified that the legislative intent behind such timelines is to prevent delay in hearing and disposal of cases, and has established that time is of essence in a CIRP.6 Delays in admission of CIRP applications are value destructive and impede the chances of a successful resolution of the corporate debtor. Given this, the Committee discussed further measures to streamline the admission process to reduce delays.

2.4. An application for initiating a CIRP under Sections 7, 9 and 10 depends largely on the evidence of default committed by a corporate debtor. In order to prove default, financial and operational creditors7 are allowed to rely on various kinds of documents. One of the ways of proving the existence of a default is by submitting records registered with IUs in this regard.8

2.5. As per the current law, financial creditors are required to submit financial information to IUs under Section 215. On the other hand, submission of financial information to IUs is optional for operational creditors. This is because operational debts tend to be small or recurring amounts that may not be properly documented and accurately reflected on the records of IUs at all times.9 Further, the possibility of disputed debts in relation to operational creditors is also higher in comparison to financial creditors.10 Additionally, as noted by the Joint Parliamentary Committee when considering provisions of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Bill, 2015, operational creditors may not have adequate resources to pay a fee to the IU for submission of information.11

2.6. The Committee deliberated whether delays at the admission stage can be reduced by facilitating greater reliance on the records of debt and default that are stored and authenticated by registered IUs. It was noted that relying on IU authenticated records that indicate undisputed information of default would enable the Adjudicating Authority to spend less time on verification of default and allow for quicker disposal of CIRP applications. As was explained by the BLRC when recommending reliance on IUs for quick access to verified financial information, “…the record of the liability is readily accessible from a registered IU, and the instance of default is also recorded within, the time taken and the cost to trigger the case of insolvency can be reduced.”12

2.7. Further, the Code allows financial creditors to rely on various kinds of documents to establish a default as IU infrastructure was just being set in place at the time of enactment of the Code. It was brought to the Committee that, with the passage of time, utilisation of the IU framework has become more robust. Figure 1 below, as sourced from the IBBI Newsletter for January-March 2022, indicates an increasing trend in the amount of information being stored and recorded with NeSL, which is the only registered IU at present. As of the end of March 2022, 5.15 lakh loan records amounting to Rs. 6.82 lakh crores had been authenticated with NeSL.13

Figure 1

Source: IBBI Newsletter for Jan-Mar, 2022

2.8. IUs now have access to the MCA-21 database and CERSAI portals, which not only increases the availability of and access to reliable data for stakeholders, but also enables them to speedily authenticate financial information.14 Moreover, since December 2017, the RBI has directed all scheduled commercial banks, small finance banks, etc. to put in place appropriate systems for submission of financial information to IUs.15

2.9. Such sustained use of IUs has led to the creation of a wider and more robust database of financial information of all entities availing credit. It was, accordingly, felt that steps should now be taken to boost the utilisation of IUs as access to such verified records will reduce the scope of challenges to the veracity of financial information. The Committee discussed that delays at the stage of admission of CIRP applications may be considerably reduced by facilitating greater reliance on IU authenticated records.

2.10. Given that banks and financial institutions have developed the practice of submitting information to IUs, the Committee agreed that mandating such creditors to rely only on IU records to establish default may expedite disposal of their applications. Therefore, the Committee decided that financial creditors that are financial institutions, and such other financial creditors as may be prescribed by the Central Government, should be required to submit only IU authenticated records to establish default for the purposes of admission of a Section 7 application. Where such IU authenticated records are not available, and for all other financial creditors, current options of relying on different documents for establishing default may remain available. Suitable amendments to Section 7 may be made for this purpose. Further, where creditors submit IU records to prove default, the Adjudicating Authority should dispose of the application speedily and should limit its scrutiny to determining if default for the purposes of commencing a CIRP has occurred.

2.11. It was also noted that requiring operational creditors to submit financial information to IUs may be too burdensome at present. Consequently, the Committee agreed that, with further development of IU infrastructure in due course, it may be considered if operational creditors should be similarly mandated to rely on IU records for establishing default.

II. EXEMPTIONS FROM THE SCOPE OF THE MORATORIUM

2.12. Upon admission of an application under Sections 7, 9 or 10 of the Code, the Adjudicating Authority declares a moratorium for the purposes referred to in Section 14. Under Section 14(3)(a), the Central Government, in consultation with any financial sector regulator or any other authority, has the power to notify transactions that may be exempted from the scope of the moratorium provided in Section 14(1). The Committee was called upon to consider whether certain transactions in respect of securities and related proceedings under securities law should be exempted under this provision by the Central Government.

2.13. At the outset, the Committee noted that Section 14(3)(a) provides that Section 14(1) shall not apply to such transactions, agreements or other arrangements as may be notified by the Central Government in consultation with any financial sector regulator or any other authority. Section 14(1), however, broadly applies to two kinds of situations – first, proceedings or actions against the corporate debtor for recovery of debt, security interest or property; and second, transactions related to transfer of assets or any legal right or beneficial interests by the corporate debtor. Thus, on a combined reading of Sections 14(1) and 14(3)(a), the Committee opined that the power to grant exemptions under Section 14(3)(a) only applies to the second scenario. In other words, under Section 14(3)(a), the Central Government does not appear to have the power to exempt legal proceedings or actions, but only transactions, agreements, or arrangements.16

2.14. Further, the Committee noted that an effective insolvency law protects the value of the insolvency estate against diminution by the actions of multiple stakeholders to insolvency proceedings and facilitates administration of such proceedings in a fair and orderly manner.17 A moratorium helps in achieving this purpose and is one of the essential features of the CIRP, which ensures that the assets of the corporate debtor are kept together during the CIRP, and the corporate debtor is continued as a going concern, thus facilitating value maximisation and orderly completion of the CIRP. In this regard the BLRC noted that “the motivation behind the moratorium is that it is value maximising for the entity to continue operations even as viability is being assessed during the IRP. There should be no additional stress on the business after the public announcement of the IRP.” 18. Also, as per the notes on clauses to Section 14 –

“The purposes of the moratorium include keeping the corporate debtor’s assets together during the insolvency resolution process and facilitating orderly completion of the processes envisaged during the insolvency resolution process and ensuring that the company may continue as a going concern while the creditors take a view on resolution of default. This also ensures that multiple proceedings are not taking place simultaneously and helps obviate the possibility of potentially conflicting outcomes of related proceedings. This also ensures that the resolution process is a collective one.” (Emphasis Supplied)

2.15. Therefore, the Committee recommended that the exemption under Section 14(3)(a) should be exercised only in exceptional circumstances, which may not hinder the smooth conduct of the CIRP and hence, should not be relaxed until found necessary from the implementation experience of the Code.

III. ISSUES RELATED TO AVOIDABLE TRANSACTIONS AND IMPROPER TRADING

2.16. Sections 43-51, 66, and 67 of the Code lay down various transactions that may be avoided by the resolution professional or liquidator (collectively referred to as “avoidable transactions”), and the actions that can be taken against erstwhile management for fraudulently or wrongfully trading in insolvency (referred to as “improper trading”). These provisions are primarily aimed at swelling the asset pool available for distribution to creditors and preventing unjust enrichment of one party at the expense of other creditors.19

2.17. Stakeholders have suggested that there is lack of clarity regarding certain aspects of proceedings for avoidance of transactions and improper trading. Notably, the Committee undertook a review of these provisions in its 2020 Report and made certain recommendations to boost the effectiveness in their enforcement.20 This includes certain amendments to the Code that the Committee felt would bring necessary clarity in law. For instance, it had recommended amendments to promote cooperation by parties with the resolution professional or liquidator for investigation of avoidable transactions and improper trading; allowing creditors to initiate such proceedings; clarifying power of liquidator to file for improper trading; etc.

2.18. The Committee discussed that the MCA may consider enacting amendments pursuant to such suggestions made in the 2020 Report. It also took note of existing issues with the implementation of provisions related to avoidable transactions and improper trading, as suggested by stakeholders. The discussion of the Committee in this regard is as follows.

i. Independence of proceedings for avoidance of transactions and improper trading

2.19. It was brought to the notice of the Committee that there is confusion regarding whether proceedings for avoidance of transactions and improper trading can continue after approval of a resolution plan in CIRP. This comes in the wake of a recent decision of the Delhi High Court in Venus Recruiters Private Limited v. Union of India21 wherein the Court inter alia opined that the applications in respect of avoidable transactions do not survive beyond the conclusion of the CIRP and once the CIRP itself comes to an end, an application for avoidance of transactions cannot be adjudicated.

2.20. The Code does not provide a deadline for the initiation of proceedings for avoidance of transactions and improper trading (in the context of both CIRP and liquidation). Once filed, the Code also does not prescribe a time limit for conclusion of such proceedings. The CIRP Regulations, however, provide that the resolution professional shall determine if the corporate debtor has entered into any avoidable transactions by the 115th day from the insolvency commencement date and intimate the IBBI of the same.22 It also requires that, by the 135th day from the insolvency commencement date, the resolution professional shall apply to the Adjudicating Authority for appropriate relief.23 Given that these timelines are directory, this Committee had in its 2020 Report noted that “prescriptive timelines for initiating proceedings against avoidable transactions and improper trading during the CIRP or liquidation proceedings may not be necessary.”24

2.21. The Committee deliberated whether proceedings for avoidance of transactions and improper trading should be independent of the CIRP proceedings. In other words, if the proceedings for avoidance of transactions and improper trading should be permitted to go beyond the conclusion of the CIRP proceedings. The Committee discussed that hypothetically, if proceedings for avoidance of transactions and improper trading were not allowed to continue after the conclusion of a CIRP proceeding, it may lead to one of two scenarios –

- First, where the Adjudicating Authority would mandatorily be required to determine the conclusion of avoidance proceedings prior to approval of the resolution plan under Section 31. This would inordinately delay the conclusion of CIRP proceedings, undermining one of the most important objectives of the Code25 – the timely resolution of the corporate debtor.

It is crucial that resolution of the corporate debtor should not be stalled due to the pendency of ancillary proceedings. Investigation and adjudication of avoidable transactions is often time-consuming. It requires a thorough examination of transactions that the corporate debtor undertook in the twilight period prior to commencement of insolvency or liquidation proceedings. This is especially cumbersome in respect of companies whose books and records do not properly document all its past transactions. Further, the resolution professional is also required to assess if a suspicious transaction would meet the requirements of the requisite avoidable transaction or improper trading as set out in the Code. The Supreme Court has laid down a “volumetric as also gravimetric analysis”26 that the resolution professional has to undertake prior to filing an application with the Adjudicating Authority for setting aside avoidable transactions.27

Not only the investigation and filing, but the adjudication of such transactions is also a lengthy process. Findings of avoidable transactions and improper trading are not purely objective assessments and involve answering questions of both law and fact. For instance, ascertaining a preference transaction would include determining if a particular transaction falls within the legal fiction created under Section 43(2), or within the exclusions under Section 43(3), etc. Consequently, it may be very difficult to conclude proceedings for avoidance of transaction or improper trading within the 330-day time limit for CIRP.

- Second, where avoidance applications would be considered infructuous if they have not been concluded before the approval of a resolution plan under Section 31. This would mean that if avoidance proceedings have not been completed before approval of resolution plan, such proceedings shall abate. Since investigation and adjudication of avoidable transactions are often time-consuming, this may allow corporate debtors an escape from reversal of suspicious pre-commencement transactions and permit them to gain undue benefit from them. Thus, this may be susceptible to misuse by errant promoters and management of corporate debtors.

2.22. The Committee noted that both the above scenarios would lead to undesirable outcomes. Consequently, it agreed that allowing proceedings for avoidance of transactions and improper trading to continue after approval of a resolution plan in CIRP would be more efficient. It is perhaps due to this rationale that the Code does not provide any specific timeline for completion of such proceedings. Section 26 of the Code provides that filing of an avoidance application under Section 25(2)(j) by the resolution professional “shall not affect the proceedings of the corporate insolvency resolution process”. In its 2020 Report, this Committee had discussed the interpretation of Section 26 and noted that “as stated in Section 26 of the Code, the filing of an application for avoidance of transactions (excluding improper trading) by the resolution professional shall not affect the CIRP of the corporate debtor.”28 Given this, it had concluded that proceedings in respect of avoidable transactions may continue beyond the timeline for the CIRP.

2.23. The Committee concurred with its earlier conclusion. It agreed that the Legislature’s intent behind Section 26 was to make proceedings for avoidable transactions independent of the CIRP proceedings. Therefore, an application for avoidable transactions is not restricted by the timelines provided for the CIRP under Section 12 of the Code. To alleviate any doubts in this regard, the Committee decided that a clarificatory amendment may be made to Section 26 so that the completion of the CIRP proceedings do not affect the continuation of proceedings for avoidable transactions or improper trading. Further, as recommended by the Committee in its 2020 Report, an amendment should be made to Section 26 to expressly include proceedings related to improper trading.29

ii. Jurisdiction of the Adjudicating Authority

2.24. The Committee also considered if a consequential change would be required to clarify the jurisdiction of the Adjudicating Authority to entertain proceedings for avoidance of transactions and improper trading beyond the CIRP period. The language of Section 60 is couched in a wide manner, and all proceedings permissible under Part II of the Code are to be adjudicated by the NCLT.

2.25. As per Section 60(1), the NCLT is the Adjudicating Authority in relation to insolvency and liquidation of corporate persons. Section 60(5)(c) provides that the NCLT has the jurisdiction to entertain or dispose of any question of priorities or any question of law or facts, arising out of or in relation to the insolvency resolution or liquidation proceedings. The Committee noted that the phrases “in relation to” or “arising out of” are of wide import, thereby extending the jurisdiction of the NCLT on subject matters related to the insolvency resolution of the corporate debtor. Further, the phrase “entertain or dispose of” suggests that the jurisdiction of the NCLT is not limited to entertaining a question of law or fact. Instead, it extends to disposal of such proceedings. Given this, the Committee felt that Section 60 read with Section 26 allows the NCLT to adjudicate over proceedings related to avoidable transactions and improper trading even after the conclusion of the CIRP. Consequently, it agreed that amendments to Section 60 may not be required in this regard.

iii. Manner of conducting avoidance proceedings after conclusion of CIRP

2.26. The Committee discussed the manner of conducting proceedings for avoidance of transactions and improper trading after the conclusion of CIRP. It noted that the resolution plan in a CIRP provides finality regarding the debts of the corporate debtor. Since any past debts of the corporate debtor stand extinguished if they are not included in the resolution plan,30 any claims against the corporate debtor that are to be pursued after approval of the plan should be specifically preserved. Consequently, the Committee agreed that the manner of conducting proceedings for avoidance of transactions and improper trading after approval of the resolution plan should be guided by the terms of the plan.31

2.27. A similar practice of preserving the enforcement of certain claims in reorganisation plans is followed in some other jurisdictions as well. For instance, a Chapter 11 plan in the US may provide for retention and preservation of claims against the debtor or its estate where any such claims are to be pursued after plan confirmation.32 This provision is often used to preserve claims in respect of preference and other such transactions of the debtor.33 The plan will also specify a person who would retain and enforce such claims, who may be the debtor, the trustee, or a representative (who is usually appointed by creditor committees). The main rationale behind requiring an explicit mention of claims that are to be retained in a plan is that “creditors have the right to know of any potential causes of action that might enlarge the estate—and that could be used to increase payment to the creditors.”34 Accordingly, creditors would factor in avoidance proceedings and the expected return from them while negotiating the terms of the plan. Another reason is that the retention of claims protects causes of actions from extinguishing by virtue of the doctrine of res judicata and judicial estoppel after the confirmation of the plan.35

2.28. The Committee discussed that a similar mechanism may be emulated under the Code. It agreed that the Code should be amended to mandate that the resolution plan should specify the manner of undertaking proceedings for avoidance of transactions and wrongful trading, if such proceedings are to be continued after approval of the plan. This includes specifying details such as the person who will continue to pursue such proceedings and the manner of payment of the costs of such proceedings. The subordinate legislation should provide a mechanism for sharing relevant details of any pending avoidable transactions and improper trading with the prospective resolution applicants, so that they can be factored in the plans submitted by them.

2.29. Moreover, the resolution plan should also include the manner of distribution of the recoveries made from the proceedings for avoidance of transactions or improper trading. Relief in respect of avoidable transactions and wrongful trading help restore the status quo prior to the occurrence of such transaction or trading. Accordingly, provisions under the Code allow the Adjudicating Authority to restore the position prior to such transaction or trading by inter alia vesting the recoveries with the corporate debtor. As discussed in this Committee’s 2020 Report, although “in most cases it may be better suited to distribute recoveries amongst the creditors of the corporate debtor… factual factors such as – the kind of transaction being avoided, party funding the action, assignment of claims (if any), creditors affected by the transaction or trading, etc. – may need to be taken into account when arriving at a decision regarding distribution of recoveries.” . This Committee had, accordingly, recommended that the decision on treatment of recoveries may be left to the Adjudicating Authority. In line with this, the Committee discussed that the resolution plan should also provide the manner of distribution of expected recoveries and the preservation of claims of expected beneficiaries, if such preservation is required, according to the commercial wisdom of the CoC. The Adjudicating Authority should have regard to the decision of the CoC regarding the manner of distribution of expected recoveries when giving final orders in proceedings for avoidance of transactions and improper trading.

2.30. When approving the resolution plan, the Adjudicating Authority should ensure that the plan contains the above details (para 2.28-2.29). Currently, the Adjudicating Authority is already required to be satisfied that a plan contains provisions for its effective implementation, before approving such a plan.36 The Committee agreed that, along with this, the Adjudicating Authority should also be satisfied that the plan provides sufficient details of the manner of continuation of proceedings for avoidance and improper trading, after its approval. Where such details have not been provided in the plan, the Adjudicating Authority should direct the resolution professional and CoC to include the same.

iv. Threshold date for look-back period

2.31. The provisions on avoidable transactions in the Code provide certain look- back periods or suspect periods. For instance, in case of preferential transactions, Section 43(4) provides for a two-year look-back period from the insolvency commencement date for related parties and one-year look-back period for unrelated parties. The threshold for such look-back period is the date of commencement of the CIRP, i.e., the date of admission of a CIRP application.

2.32. In practice, the admission or rejection of an application takes longer than the 14-day time limit provided in the Code. Given this, the look-back period for avoidable transactions may not be able to capture a significant portion of transactions that occurred before the filing of a CIRP application. This may reduce the effectiveness of the provisions related to avoidance of transactions. Further, it may also give corporate debtors a perverse incentive to delay admission of CIRP so as to reduce the scope of avoidable transactions. Thus, the Committee discussed if the threshold for the look-back period for avoidance of transactions under the Code should be modified.

2.33. In this regard, the UNCITRAL Legislative Guide on Insolvency Law concurs with the observations of the Committee. It notes that the effectiveness of provisions on avoidance would substantially reduce in jurisdictions where the commencement of insolvency proceedings is time-consuming. To remedy this, it suggests that the look-back period may be traced back from the date of the application for commencement of insolvency proceedings. It discusses that –

“The event or date specified by the law will depend upon other design features of the insolvency regime such as the requirements for commencement, including whether there is a potential for delay between the application for, and commencement of, insolvency proceedings. For example, if commencement typically takes several months from the time of application and the suspect period is a fixed period relating back from the effective date of commencement, then several months of that period will be taken up by the period of delay between application and commencement, thus limiting the potential effectiveness of the avoidance powers… To address situations where there is the potential for delay to occur, an insolvency law could stipulate that the suspect period applies retroactively from the date an application is made…”37 (Emphasis Supplied)

2.34. Given the above, the Committee decided that the threshold date for the look- back period for avoidable transactions under the Code should be the date of the filing of application for initiation of CIRP, i.e., the initiation date. Further, transactions from the initiation date until the insolvency commencement date should also be included in the look-back period. In this regard, suitable amendments may be made in Sections 43, 46 and 50. Further, the Code may clarify that where multiple CIRP applications have been filed and admitted regarding the same corporate debtor, the date of filing of the first such application should be considered as the ‘initiation date’.

IV. CURBING SUBMISSION OF UNSOLICITED RESOLUTION PLAN AND REVISION OF RESOLUTION PLANS

2.35. During the CIRP, the resolution professional is required to publish an invitation for EoIs calling prospective resolution applicants to submit their EoI.38 After the EoIs are submitted, the resolution professional issues an RFRP which provides the deadline for submitting the resolution plan(s).39 It was brought to notice of the Committee that on certain occasions additional resolution plans are submitted after the deadline in the RFRP, either for the first time or as revision of a plan submitted within the deadline. Such resolution plans are submitted on an unsolicited basis without the consent of the resolution professional or the CoC.

2.36. The Committee noted that during the CIRP, the resolution professional is responsible for the conduct of the process40 and she is required to invite prospective resolution applicants who fulfil such criteria as may be laid down by her with the approval of the CoC41. Further, the IBBI is empowered to impose conditions in relation to such invitation42 and it has laid down regulations for submission of plans during the CIRP. As per the CIRP Regulations, the resolution plans are submitted through a two-stage process. First, the resolution professional publishes an invitation for EoI and thereafter, the resolution applicants submit their EoI to participate in the resolution process of the corporate debtor.43 An EoI received after the timeline specified in the invitation is to be rejected.44 Second, the resolution professional prepares a list of resolution applicants and issues inter alia the information memorandum, evaluation matrix and the RFRP along with details of the process and corresponding deadlines.45 The resolution applicants are required to submit resolution plans within the specified timeline. Further, the timeline for submission of resolution plans can only be extended by the resolution professional with the approval of the CoC.46

2.37. The present procedure for submission of resolution plans under the CIRP Regulations has been a result of successive developments to address the issue of late submission of resolution plans. Initially, a resolution applicant was required to submit a resolution plan 30 days before the expiry of the maximum time period permitted for completing the CIRP.47 This approach gave the impression that the resolution plan cannot be finalised until 150 days from the commencement of the process. To facilitate early resolution, the resolution applicant was required to submit the plans in accordance with the time given in the invitation made under Section 25(2)(h).48 In due course, the IBBI came across instances of submission of resolution plans after the time stipulated in the invitation.49 This issue of late bids was also recognised by the Government, which noted that the regulations will bring further clarity by laying down mandatory timelines and procedure in this regard.50 In this background, the IBBI specified a two-stage process of invitation of EoIs and RFRP and model timelines for each activity.51

2.38.The Committee noted that despite these regulatory developments, resolution plans are received by the resolution professional after the deadline stipulated in the EoI and the RFRP in some instances. Broadly, the Adjudicating Authority and the NCLAT deal with two types of situations in relation to delayed submission of resolution plans.

(i) First, where resolution plans are submitted after the stipulated deadline and the same are not considered by the resolution professional or the CoC. In certain cases, tribunals have directed the resolution professional or the CoC to consider a resolution plan after the deadlines specified in the EoI or RFRP by giving precedence to the principle of maximisation of value over the procedure laid down by the regulations.52 Conversely, in some cases tribunals have upheld the sanctity of the timelines provided under the regulations.53

(ii) Second, where despite late submissions, resolution plans are considered by the resolution professional or the CoC. In a recent case, where a resolution plan submitted beyond the stipulated deadline was approved by the CoC, it was held that the tribunals are not vested with the jurisdiction to review commercial decisions of the CoC and the resolution plan was approved.54 However, it has also been held that the CoC in its commercial wisdom cannot permit an EoI submitted after the deadline, especially when the resolution professional did not act in a bona fide manner and concealed material facts from the CoC.55

2.39. Similarly, the Committee noted that the CIRP Regulations do not give a right to the resolution applicants to unilaterally revise or improve resolution plans. However, tribunals have in some instances observed that revisions to plans submitted should be considered by the CoC if it is during the CIRP period and a plan has not yet been approved by the CoC. This approach is adopted to ensure maximisation of value available to creditors.56

2.40. Divergent judicial approaches regarding the submission or revision of plans after stipulated deadlines results in uncertainty in the process. It also dis-incentivises market participants from abiding by the timelines provided in the CIRP Regulations.

2.41. Consequently, the Committee deliberated on the manner of balancing the two principles of value maximisation and sanctity of the CIRP procedure. The primary objective of the Code is to ensure the time-bound resolution of insolvency which will result in maximisation of value of the assets of concerned stakeholders, promotion of entrepreneurship, and ensuring greater availability of credit and balancing the interests of all stakeholders concerned. In order to achieve this objective, the Code has created institutions like the IBBI, insolvency professional agencies, insolvency professionals and IUs. Under the Code, the IBBI is empowered to lay down regulations detailing inter alia the procedure for corporate insolvency and liquidation processes. These regulations are made in furtherance of the objectives of the Code and seek to strike a balance among them. Consequently, insolvency professionals and the Adjudicating Authority are required to ensure compliance of the same.

2.42. Although deference to the wisdom of the CoC in commercial matters is an established norm, such commercial wisdom should be exercised as per the procedure laid down by the Code and the regulations. Where the regulations specify the procedure for conducting the CIRP, unless they are ultra vires to the Code, participants are required to comply with them. Non-compliance of the same undermines the certainty, predictability and transparency of the process thereby making it unfair for the participants and being detrimental to the development of a market for resolution plans. Since the regulations are framed in furtherance of the objectives of the Code and its provisions, a reliance on its objectives (value maximisation) for non-compliance of the procedure will go against the scheme of the Code.

2.43. The report of the Standing Committee on Finance also observed that late and unsolicited plans and revisions to submitted plans are often received after the highest bid is in public domain.57 It further noted that the CoCs have significant discretion in evaluating and accepting late and unsolicited plans, and suggested that accepting late plans should not be permitted in order to maintain the sanctity of the proceedings.

2.44. Considering the above, the Committee decided that the regulations should clearly lay down a mechanism for reviewing late submissions of (or revisions to) resolution plans. Further, suitable amendments should be made in the Code to ensure that the procedure provided in the regulations has due sanctity.

2.45. The Committee agreed that the CIRP Regulations may allow the CoC to opt for a Swiss challenge method for considering plans and revisions to plans submitted after the deadline in the RFRP. Through this challenge method, the CoC may consider any unsolicited plans or revisions based on a decided criteria that is based on the commercial viability of the plan. The decision to allow Swiss challenge method and the details thereof should be recorded in the RFRP. Further, the CIRP Regulations may require the CoC to specify, in the RFRP, the number of revisions that are permissible by prospective resolution applicants and the timeline for such revisions. ‘Revisions’, in this respect, would not include any clarifications or modifications made pursuant to negotiations with the CoC. Further, the RFRP should provide the last date by which any plans or revisions may be submitted and the CoC not be permitted to consider any plans or revisions after such date. Additionally, the Committee noted that the CoC should provide a reasonable time-period in the RFRP for the submission of resolution plans, in order to provide participants with a fair opportunity to submit their plans before the deadline. This may aid in reducing the number of participants who seek to submit their plans after the deadline in the RFRP.

2.46. Pursuant to the above discussions, it may be noted that the IBBI issued a discussion paper in August 2021,58 aligned with some of the recommendations made by the Committee. Based on this, amendments have been carried out in the CIRP regulations in September, 2021 which incorporate certain recommendations made by the Committee. This includes amendments to Regulations 36A, 36B and 39 which govern the invitation for EoI, RFRP and approval of resolution plans, respectively.59 The amendments have clarified the manner in which modification to the invitation of EoI, the RFRP and the evaluation matrix may be made and to provide a limit on such modifications.60 The resolution professional has been enabled to allow modification of a resolution plan submitted under this provision if the RFRP so envisages, but not more than once.61 Additionally, the manner of making revisions using a challenge mechanism and preventing late and unsolicited plans from being considered by the CoC have also been provided for in the regulations.62

V. TIMELINE FOR APPROVAL OR REJECTION OF RESOLUTION PLAN

2.47. The approval of a resolution plan by the Adjudicating Authority is the last step in a CIRP. However, often this last step becomes a significant hurdle to the resolution and rehabilitation of the corporate debtor. The Committee noted that there are significant delays in the approval or rejection of resolution plans by the Adjudicating Authority. The Report of the Standing Committee on Finance has identified delays in approval of the resolution plan by the Adjudicating Authority as one of the main reasons for delays in the insolvency resolution process.63

2.48. Such delays can be partly attributed to the applications filed by disgruntled resolution applicants or other stakeholders questioning the distributions contemplated under a resolution plan. Some part of the delay can also be attributed to the heavy caseload before the NCLTs. The Committee noted that such delays are concerning. In any insolvency process, time is of the essence and delays in the process may cause significant erosion of the value of the corporate debtor’s assets.

2.49. Further, delays also discourage potential resolution applicants from participating in the process as they adversely affect the applicant’s commercial assessments. A resolution applicant whose resolution plan is pending approval by the Adjudicating Authority may also attempt to seek modifications to the resolution plan or withdraw it altogether as the commercial basis underlying the resolution plans may change during the pendency of the application for approval of the resolution plan. Not only does this go against the Code’s objective of value-maximisation for stakeholders, but it could also trigger the liquidation of the corporate debtor.

2.50. While the Hon’ble Supreme Court has disallowed attempts to seek modifications of the resolution plan64 or withdrawal of the resolution plan,65 the apex courts has also observed that –

“It would also be sobering for us to recognize that whilst this Court has declared the position in law to not enable a withdrawal or modification to a successful Resolution Applicant after its submission to the Adjudicating Authority, long delays in approving the Resolution Plan by the Adjudicating Authority affect the subsequent implementation of the plan. These delays, if systemic and frequent, will have an undeniable impact on the commercial assessment that the parties undertake during the course of the negotiation.” (Emphasis supplied)

The Court, therefore, called upon the Adjudicating and Appellate Authority under the Code to “endeavour, on a best effort basis, to strictly adhere to the timelines stipulated under the IBC and clear pending resolution plans forthwith.”

2.51. Given the above, the Committee agreed that amendments should be made to Section 31 of the Code to provide that the Adjudicating Authority has to approve or reject a resolution plan within 30 days of receiving it. This 30-day time-period shall be subject to the overall time-period specified for the completion of the CIRP under Section 12. Further, where the Adjudicating Authority has not passed an order approving or rejecting the resolution plan within such 30-day time-period, it may be required to record reasons in writing for the same.

VI. CONFLICTS OF INTEREST WITH PROFESSIONALS

2.52. The Code provides for the interim resolution professional/resolution professional to seek the assistance of various professionals in the performance of their duties and confers on them the authority to appoint such professionals as necessary.66 The Code also provides for the IBBI to specify the manner of their appointment by way of regulations.67 The ability of interim resolution professionals/resolution professionals to engage professionals including lawyers and accountants in the performance of their duties has given rise to concerns regarding the purpose of such engagements, its implications on the costs of the CIRP proceedings, conflicts of interest and related concerns of accountability and transparency. There have been instances where the NCLTs have raised concerns about the large number of people engaged by the resolution professional for providing various services, outsourcing of responsibilities to them, and the exorbitant costs incurred towards fees of the professionals.68

2.53. The Committee discussed whether there should be oversight or regulation of scenarios involving conflicts of interests between professionals engaged by stakeholders in a CIRP. It noted, however, that the current regulations provide several safeguards for this purpose.

2.54. The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (Insolvency Professionals) Regulations, 2016, which regulate insolvency professionals provides for a Code of Conduct in the First Schedule. The Code of Conduct contemplates situations involving conflicts of interest and mandates the insolvency professional to act with integrity and objectivity in his professional dealings and ensure decision-making without “any bias, conflict of interest, coercion, or undue influence of any party.”69 The Code of Conduct also mandates the insolvency professional to disclose any conflict of interests and particulars regarding such conflict to the stakeholders, at any time during the assignment.70

2.55. Further, Regulation 27 of the CIRP Regulations details the manner in which registered valuers and other professionals should be engaged by the interim resolution professional /resolution professional so as to avoid any conflict of interests.71 Regulation 27(3) also provides that the appointment is to be done “on an arm’s length basis following an objective and transparent process” and prohibits certain categories of persons from being engaged as professionals. These include relatives of the resolution professional, and partners or directors of the insolvency professional entity of which the resolution professional is a partner or director.

2.56. The IBBI has also issued a circular dated January 16, 201872 that mandates insolvency professionals to disclose any relationship with professionals engaged by them, and to ensure disclosure of any relationship of the professionals engaged, including with themselves. The circular also stipulates the nature of relationships that should be disclosed and the period within which the disclosures are to be made.

2.57. Given the above, the Committee agreed that further disclosures of conflicts may be provided in subordinate legislation, if required, and that amendments to the IBC for this purpose may not be necessary.

VII. STANDARD OF CONDUCT FOR THE COC

2.58. The CoC is entrusted with critical commercial decision-making powers in the CIRP under the Code. It not only takes key decisions regarding the conduct of the business of the corporate debtor during the CIRP but is also tasked with the responsibility of assessing the viability of the corporate debtor, and determining the manner in which its distress is to be resolved. Thus, the success of a CIRP hinges on the manner of functioning of the CoC. It was brought to the Committee that there have been a few instances of improper conduct by members of CoCs that have raised concerns amongst stakeholders.

2.59. In some instances, the representatives sent by members of the CoC are neither adequately apprised of their role, nor adequately empowered to take decisions. This “causes delay and allows depletion of value”73 which goes against two crucial objectives of the Code, i.e., timely resolution and maximization of value available for stakeholders. This is despite a circular issued by the IBBI which provides that members of the CoC should send personnel “who are competent and are authorised to take decisions on the spot and without deferring decisions for want of any internal approval from the financial creditors.”74 In other instances, the tribunals have noted missteps of CoCs, such as undertaking adjudication beyond their powers75, violating legal procedural requirements76, etc.

2.60. It is also pertinent to note that presently, the conduct and decision making of the CoC is not subject to any regulations, instructions, guidelines etc. of the IBBI. Unlike insolvency professionals, IUs and IPAs, the IBBI does not exercise regulatory oversight over financial creditors who form the CoC. Given this, stakeholders have suggested that CoCs should be guided by a code of conduct which lays down the expectations that financial creditors are required to meet when acting in the CoC.

2.61. The Committee had previously deliberated on this issue in its 2020 Report and suggested that “institutional financial creditors should take necessary steps to ensure that their representatives are capable of discharging their duties in a timely and efficient manner.”77 To enable this, the 2020 Report had recommended that–

(i) Financial institutions should build strong verticals for stressed asset management that go through period performance review. These verticals should be staffed with personnel that have adequate training and expertise.

(ii) The personnel that represent financial creditors in meetings of the CoC should be sufficiently empowered to take decisions on the spot, and effectively discharge their duties.

(iii) Industry bodies, like IBA, should develop guidance to help members of the CoC in discharging their duties consistent with the letter and spirit of the Code.

2.62. The Committee took note of the above and discussed that the recommendations made in its last report have not resulted in a change in the conduct of financial creditors in the CoC. It felt that since the CoC drives the CIRP and is given wide powers to utilise its commercial wisdom, such powers should be balanced with adequate accountability. Since the decisions of the CoC impact the life of the corporate debtor, and consequently its stakeholders, it needs to be fair and transparent in its decisions. Therefore, the Committee agreed that it would be suitable for the IBBI to issue guidelines providing the standard of conduct of the CoC while acting under the provisions governing the corporate insolvency resolution process, pre-packaged insolvency resolution process and fast track insolvency resolution process. This may be in the form of guidance that provides a normative framework for conducting these processes. In order to empower the IBBI to issue such guidelines, the Committee recommended that appropriate amendments may be made to Section 196 of the Code. Further, the Committee discussed that the MCA may consult with relevant financial sector regulators such as SEBI and RBI, to frame an appropriate enforcement mechanism for the standard of conduct. Several members of the Committee agreed that the IBBI may be most suitable to carry out such enforcement. A discussion paper addressing the standard of conduct has already been issued by the IBBI pursuant to the discussion of the Committee.78

2.63. The Committee also discussed the scope of the standard of conduct. It noted that the standard of conduct should lay down the rules of procedural fairness and efficiency that the CoC is required to abide by. However, the Committee cautioned that the standard of conduct should not be utilised to expand or limit the substantive powers of the CoC and should not provide guidance that diminishes its commercial wisdom. Additionally, such a standard of conduct should elucidate the role of the CoC vis-à-vis insolvency professionals, in line with the discussion in the 2020 Report of this Committee.79

VIII. STAKEHOLDERS CONSULTATION COMMITTEE

2.64. In its 2015 Report, the BLRC noted that the swiftness and efficiency of the liquidation process has always been dependent on the liquidator.80 Whereas the BLRC designed the CIRP to be driven by creditors of the corporate debtor, the liquidation process is meant to be driven by the liquidator. Thus, the Code does not envisage a creditors’ committee in the liquidation process. It does, however, allow creditors to participate in the liquidation process to a limited extent.

2.65. The Code currently authorises the liquidator to consult any of the stakeholders who are entitled to a distribution of proceeds and such consultations are not binding on the liquidator.81 Further, Section 37(2) requires the liquidator to provide financial information to any creditor who requests for the same. In order to provide a formal structure for consultation under Section 35(2), the Liquidation Process Regulations specify the constitution of the SCC. The liquidator is required to constitute the SCC within 60 days of the liquidation commencement date. Where the liquidator differs from the advice of the SCC, she needs to record reasons in writing.82

2.66. It was brought to the notice of the Committee that the role of the SCC should be reviewed and suitable provisions should be enacted in the Code to give it statutory recognition.

i. Statutory recognition of the SCC

2.67. First, the Committee considered whether there is a requirement to codify the role and powers of the SCC in the statute. Notably, this issue was deliberated by the Committee in its 2020 Report and it agreed that the SCC, as an advisory body, had utility within the liquidator framework under the Code. However, no recommendations were deemed necessary to give statutory recognition to the SCC.

2.68. The Committee noted that the SCC is a consultative body which is meant to guide the liquidator on certain key decisions. The regulations provide a detailed framework for the SCC and the practice of seeking consultations from the SCC is regularising. The requirement of constituting a SCC in the liquidation processes has also been upheld by Adjudicating Authorities under the Code.83 The Committee noted that the practice of seeking consultations from the SCC is already settling. Consequently, the Committee concluded that at this stage there is no gap in the Code requiring the need to statutorily encode enabling provisions for recognition of the SCC.

ii. Mandatory stakeholder consultation by the liquidator

2.69. Section 35(2) of the Code currently empowers the liquidator to consult stakeholders. It was brought to the Committee that conducting such consultation may be made mandatory to ensure more comprehensive oversight over the liquidator. Thus, the Committee deliberated whether undertaking consultations with the SCC should be mandatory or at the discretion of the liquidator. It noted that this would depend on the degree of involvement of creditors and oversight over the liquidator desired at the liquidation stage.

2.70. The UNCITRAL Legislative Guide on Insolvency Law acknowledges that it is generally not important for creditors to intervene in proceedings or participate in decision-making during the liquidation process as the process is driven by the liquidator.84 However, it notes that creditors may be able to provide valuable expert advice or information on the debtor’s business. Further, it notes that it may be desirable for creditors to receive reports on the progress of a liquidation proceeding to boost confidence and transparency. In specific instances, such as the sale of assets in the context of liquidation proceedings, it suggests that creditors may be given a more significant role to play to boost the value of returns from such sale.85

2.71. It is perhaps due to this rationale that erstwhile insolvency laws in India provided for certain creditor committees in winding up processes. The CA, 195686 and the CA, 201387 provide for the constitution of committees by the liquidator, primarily composed of the creditors, on the directions of the Court/Tribunal. These committees exercise inspection or advisory powers during the winding-up process under the CA, 1956 or 2013, respectively.88 The role of these committees was specific to the legislative model adopted therein and the constitution of these committees was at the discretion of the Court/Tribunal. For instance, the committee of inspection under the CA, 1956 was to act with the liquidator, while the advisory committee, under the CA, 2013 advises the company liquidator.89

2.72. Similar committees are also provided in the liquidation processes of other jurisdictions, which exercise varying degrees of supervision and consultation in relation to the liquidator. The insolvency law of the UK permits creditors to appoint a liquidation committee which sanctions certain powers of the liquidator, including powers relating to sale of the debtor’s property.90 In Canada, the liquidator is required to give notice to creditors, contributories, shareholders or other members of the company prior to sale of the debtor’s assets.91 In Australia, there exists a general duty on the liquidator to consult with the committee of inspection constituted during the liquidation process.92

2.73. The Committee noted that despite some variations in international practice, the constitution of creditor committees during the liquidation process and some form of supervision of the functions of the liquidator, particularly in relation to sale of assets, is a prevalent practice. The requirement for liquidator to consult or seek sanction from such committees prior to performing certain functions was noted to be common in several jurisdictions. The Committee further noted that the SCC, similarly, would be able to offer valuable commercial insight to the liquidator in relation to several matters, including the sale of assets. Simultaneously, it was observed that such committees are, thus, also enabled to act as a check on the actions of the liquidator.

2.74. Consequently, the Committee concluded that Section 35(2) may be suitably amended to provide that the liquidator must mandatorily consult with the SCC so as to ensure that the SCC is able to provide commercial inputs on the functions of the liquidator as well as conduct oversight over the liquidator. The manner of and issues requiring such consultation may be provided in the subordinate legislation.

2.75. Pursuant to the discussions of the Committee above, the IBBI issued a discussion paper,93 wherein amendments to the Liquidation Process Regulations were suggested in order to require the liquidator to consult with the SCC for all significant matters pertaining to the liquidation process. Thereafter, the Liquidation Process Regulations have been amended to provide for the requirement to consult the SCC for appointment of professionals to assist the liquidator and their remuneration,94 as well as for sale of assets.95

IX. CONTRIBUTION BY SECURED CREDITORS