In a new report, ICRICT evaluates the forthcoming OECD solution to tax multinationals and calls for a fair and comprehensive reform that would tax multinationals as single firms, using formulary apportionment based on objective factors, together with a minimum effective corporate tax rate of 25%.

A significant challenge to resource availability – and to the prospects for sustainable development stems from the iniquities of international tax rules, as 40% of overseas profits made by multinationals around the world are transferred to tax havens. Low income countries are the most affected since they have limited alternatives for raising revenue. Faced with the scale of this problem, the OECD will launch its proposal to reform the way multinationals are tax (with a final agreement to be found by 2020) next Wednesday. The pressure to reach a consensus means the risk of water down solutions is high:

Ø Any reform actions taken now should be the first step towards taxing multinational as single and unified firms, using formulary apportionment based upon objective factors, and result in a system that is simpler, easier to administer, more efficient and more equitable.

Ø We reject the likely proposal of splitting “routine” and “residual” global profits of multinationals and making only a fraction of the latter subject to formulary apportionment. This will keep the existing dysfunctional rules in place to determine how the majority of multinationals profits are taxed and result in little reallocation of taxing rights.

Ø We are concerned about the likelihood that this reform is going to benefit OECD countries first and foremost, as the proposal results in a limited shift of taxing rights, and only to market jurisdictions. An equitable distribution of taxing rights can only be achieved through a balanced formula which includes supply and demand factors, as allocation based on sales tend to advantage advanced economies who consume more whilst developing countries significantly benefit if employment is included in any allocation formula.

Ø We believe a global minimum effective tax should be set at 25%, as we are fully aware that what is now set as a global minimum may become in the future the global maximum.

The credibility of OECD as the appropriate body to continue to lead this work remains in question. Much still needs to be done to ensure effective participation and representation of developing countries. We await with interest the outcome of the ongoing negotiations, but as a Commission we do not regard the likely outcome in 2020 as an end point, but rather as the first step towards creating a genuinely fair international tax architecture. It will require multilateral discussions extending well beyond current process and involving the United Nations system, because it is the only forum where all countries are represented.

Why is the current international tax system failing?

The current system is based on the fiction of treating the various affiliates of multinationals as if they were independent of each other (the so-called “arm’s length principle”). This has encouraged multinationals to create complex tax-avoidance structures by forming hundreds of affiliates in convenient jurisdictions. These arrangements are conceptually straightforward: low profits are declared in high-tax jurisdictions, both in developed and developing countries, through the use, for instance, of limited risk structures, excessive debt and deductions for the right to use intangibles.

This system allows to multinationals to legally allocate their profits in low-tax jurisdictions or tax havens, and, consequently, pay almost zero tax.

What is the impact on the prospects of sustainable development?

When global corporations and the super-rich dodge their tax paying responsibilities, it is the poorest countries and people who lose most. Governments are left with the options of cutting back on the essential spending needed to fight inequality and poverty and the climate change; or make up the shortfall by increasing taxes such as VAT, which hit ordinary citizens harder.

The impact of corporate tax dodging is even stronger for developing countries, since they are more dependent on corporate taxes than developed ones. Corporate tax represents 15% of total tax revenues in Africa and in Latin America, compared to 9% in OECD countries.

What could change now?

With the accelerated digitalization of the economy, the amounts diverted are constantly increasing, now denounced by the most orthodox institutions, such as the International Monetary Fund. But the most important move came from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which after a first phase of positive though very limited changes, proposed, earlier this year, to challenge the very foundation of the international tax system, which is the ability of multinationals to report their profits in the subsidiary of their choice.

In an effort to gain legitimacy, the OECD has offered developing countries a place at the negotiating table by creating a group called the “inclusive framework”. It is today, with 134 member countries, the de facto place in which tomorrow’s global tax system is decided on.

What is being discussed?

Negotiations are ongoing within the Inclusive Framework on reforms under two key challenges – called “pillars”.

Pillar 1 – Taxing rights. Where should corporate profits be taxed?

Under the current system many countries have little or no right to tax profits generated from sales and other digital activities on their territory, because a company needs to be physically present in order to be taxed and because the current rules don’t take account of the value which customers and digital users bring to a company.

The new approach now aims to allocate a portion of multinationals profits to market jurisdictions starting from their total global profits.

Pillar 2 – Should all corporations be required to pay a minimum rate of tax?

The OECD wants to introduce a global minimum effective tax rate in order to ensure that all corporate profits are taxed at a minimum level. It could remove the incentive for companies to move their profits to low or zero corporate tax countries and put an end to the damaging tax competition between countries.

Why shouldn’t the reform separate “routine” and “residual” profits?

The new approach to allocate income of multinationals that is being proposed by the OECD would keep the international tax system in place for most of the profits (so called “routine profits”), allocate only fraction of the remaining global profits of the multinationals (so called “residual profits”) through a formula.

In that case, companies could continue to report their profits wherever they want for most of their activities, allowing only a small portion of the tax to be reallocated, possibly not more than 20%.

We reject the approach of separating ‘residual’ from ‘routine’ profits, since it is not possible to distinguish between residual or routine profits of a multinational.

Why is it crucial to set up a fair distribution of taking rights?

It is crucial to understand that different formulae will likely result in significantly different distributional outcomes among countries.

Choosing to allocate taxing rights by reference to sales alone, as the OECD is considering, would disadvantage countries with relatively small domestic markets, or those with substantial exports, particularly of natural resources and tourism.

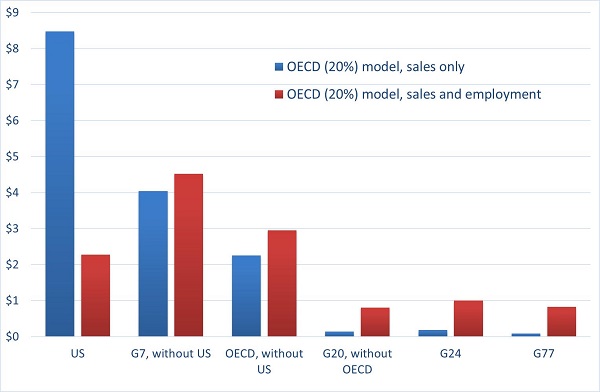

As rich countries consume more, allocation of profits by sales only is likely to result in an unequitable distribution between countries, as shown by a recent research[1] on the redistribution of taxing rights. If the OECD proposals about the separation between residual and routine profits were to be accepted, multinationals could continue to report their profits wherever they want for most of their activities, allowing only a small portion of the tax to be reallocated. If, for example, this portion represents 20% of the total, the impact differs a lot if the key to distributing these profits depends only on the volume of sales, excluding the “employment” factor. Rich countries would be allocated more profits, and therefore more taxes, as shown in the graph below.

Projected per capita revenue increases, OECD (20%) model

Source: “Global inequalities in taxing rights: An early evaluation of the OECD tax reform proposals” by Cobham, Faccio, Fitzgerald (2019). https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/j3p48/

The solution we have advocated within ICRICT is a global formula that would ensure that multinationals’ global profits – and hence the associated taxes – could be apportioned between countries according to objective factors. It is imperative that those should include not just sales, but also employment (at headcount, rather than at payroll level) to truly benefit developing countries.

Why should the reform be about all multinationals and not only the digital ones?

As the digital economy is fast becoming the economy itself, any solution should be comprehensive and deliver a sustainable international tax architecture fit for the 21st century. In fact, ring-fencing the digital economy is impossible, since all businesses are increasingly using digital technologies as part of their business practices.

What should we have a high effective global minimum tax?

We support the current proposal for a global anti-base erosion tax. We are concerned by the probability of a low Alternative Minimum Tax rate becoming the international benchmark which effectively incentivizes a “race to the minimum”.

Some developing countries fear that by abandoning the weapon of tax incentives, they will no longer be able to attract companies. Yet, if the international community agreed on a sufficiently high rate, this would put an end to the race to the bottom that we are witnessing, whose only winners are the multinationals. This measure would remove the raison d’être of tax havens, while ensuring that all States have access to those resources essential for development.

In our view, this effective global minimum tax should be set at an agreed minimum rate of 25%, which is determined by the current corporate average tax rate in G7 countries.

Why must the United Nations system be involved in the discussions?

Whilst the institutional framework is on paper more inclusive, developing countries must be equal participants in the development of the rules of international taxation and not mere participants in processes where their views are sought merely for the appearance of broad consultation. This can only truly be possible in a space which allows equal and effective participation for all countries, including the poorest.

Discussions towards creating a global tax body within the United Nations should continue, as international norm setting is only legitimate in a democratic multilateral space only the UN can provide.

ABOUT ICRICT: The Independent Commission for the Reform of International Corporate Taxation aims to promote the international corporate tax reform debate through a wider and more inclusive discussion of international tax rules than is possible through any other existing forum; to consider reforms from a perspective of public interest rather than national advantage; and to seek fair, effective and sustainable tax solutions for development.

[1] Similar results on the significantly different distributional impact of different allocation factors are also shown in recent IMF research https://www.imf.org/~/media/Files/Publications/PP/2019/PPEA2019007.ashx p34.