Abheek Barua*

Is private consumption finally going to get the much needed rural push? Rural demand has been picking up in recent months. This is visible in sales of big ticket items such as tractors and latest corporate earnings data of FMCG companies. However, the extent of this pick up is dependent on a number of factors. Firstly, a good monsoon alone will not do the trick. Adequate procurement and the effectiveness of MSPs to act as a floor for crop prices will be crucial. Even if MSPs are increased substantially, the actual income realisation of farmers will be determined by what percentage of crops will be bought at these prices. Secondly, rural wages have been declining in recent months and the revival in both nominal and real rural wages will be essential for a sustainable recovery in rural demand. We think that with the increase in rural inflation and uptick in construction activity some of the decline in rural wage growth is likely to be reversed. The bottom-line is that while there are pockets of the rural demand story that are showing strength, we are still a step away from a full blown rural pick up.

Analysing the rural demand pick-up

No doubt that rural demand has shown some green shoots in recent months with consumer good companies posting higher earnings in January-March 2018 quarter, big ticket items like tractors which are usually seen as a lead indicator of rural demand picking up and sales of multi-purpose vans and motorcycles remaining strong. According to a recent study by Nielsen India, rural growth outpaced urban demand, rising by 13.5% in Q4 FY18.

Clearly, rural demand is recovering from the setback due to demonetisation in 2016 and disruptions felt due to the implementation of GST. However, we have our reservations over the extent of this increase. This is because:

Clearly, rural demand is recovering from the setback due to demonetisation in 2016 and disruptions felt due to the implementation of GST. However, we have our reservations over the extent of this increase. This is because:

1. Rise in big ticket items—the loan waiver factor: The recent jump in items such as tractor sales could have at least been driven by the farm loan waivers. A similar phenomenon was witnessed during 2009 when the government had waived farm loans and tractor sales grew by 30% yr. Therefore, it is uncertain whether the recent increase is a one-time spike or a reflection of genuine improvement in the rural income situation.

2. Bounce over a weak base: Secondly, the increase in rural demand is coming over two years of weak growth as demonetisation took a hit on consumption. Therefore, this could be a bounce back from the 2016 lows and not necessarily translate into the required higher momentum in rural demand.

3. Rich farmers driving consumption, inequality remains high: Thirdly, despite the fall in agriculture output in FY18, rural demand might have risen on the back of affluent farmer spending and the rise in items such as tractor sales could partly capture this. As per the PRICE income survey (ICE 360, People Research on India’s Consumer Economy), 34% of the rural consumption comes from only the top 5% (according to income) of the rural population while 33% comes from the bottom 50%. Therefore, strong demand from the more affluent rural population could have outweighed the decline in demand from majority of the rural population. This could change if farm gate prices for poorer farmers are increased and consequently income growth of not just the higher income farmers but also those at the middle or bottom of the pyramid rises.

Will rural wages rise enough to support consumption?

The most important leg of the rural demand puzzle is that while rural demand indicators are looking up, rural wage growth on the other hand has seen a decline. Nominal rural wage growth has been moderating since the middle of 2017. Wage growth declined to 3% in February 2018 from over 7% in April last year. Also, real wage growth has seen a secular decline over the last year and has now turned negative.

For a strong and sustainable rise in rural consumption, an increase in rural wage growth is

essential. Therefore, we look at why rural wages have been declining and how are they likely

to trend in the coming months.

What is driving rural wages?

1. Looking beyond the farm sector

Usually, rural wage growth is linked with the performance of monsoons and agriculture growth. However, the nonfarm sector of the rural economy bears an equal if not higher influence over overall rural wage pressures. To put things in perspective, non-farm activities such as construction, manufacturing and services account for over 60% of the value added in rural output. The break-up of rural wage growth into agri and non-agri shows that while agricultural wages have seen a sharper decline, the fall is not restricted to the farm sector.

- Both agri and non-agri wages have declined, the former more than the latter: Agriculture wage growth declined from close to 9% in April 2017 to 2.3% in February 2018 with nonagricultural wage growth also moderating from 5% to 3.7% during the same period.

- Non-farm wages have an impact on farm wages: A recent RBI study (Rural Wage Dynamics in India: What Role Does Inflation Play? RBI Working paper, Sujata Kundu, April 2018) finds that construction wages have an impact on agricultural wages with a two-month lag emphasizing the linkages between non-farm and farm sector wages. We tested the linkage between agri and non-agri wages and found similar results that non-agri wages have a statistically significant impact on agricultural wages (for detailed results of the Granger Causality test see Appendix).

Construction wage growth rose for during 2016 and 2017 driving up agriculture and overall rural wage growth during this period. However, in recent months, construction wage growth has declined sharply (from over 6% in April 2017 to 3.2% in February 2018) and is likely to have pulled down agriculture and overall rural wage growth. The decline in construction wages is puzzling given the increase in annual growth rate in construction GDP. However, if one looks at the quarterly momentum of construction activity, we find that it has slowed down in the last two quarters and correlates with the decline in construction wages during the same period.

Looking ahead, given the expected pickup in the non-farm sector – with manufacturing activity showing signs of revival, GST related disruptions fading away, and continued push to construction by the government – the fall in agri wages might moderate and overall wage growth outlook might improve.

2. A good monsoon= higher rural incomes? The procurement angle

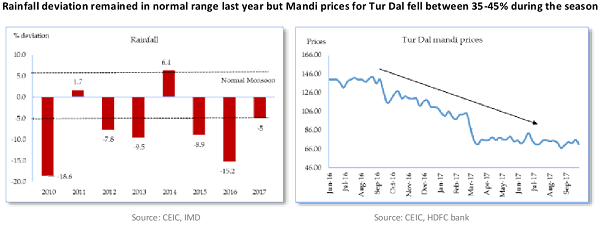

Usually a good monsoon – one that has a favourable temporal and spatial distribution – results in higher agricultural production. However, a normal monsoon does not necessarily imply higher rural incomes and demand. Good rains can result in over production of certain crops and unless there is some external intervention such as adequate procurement or increase in exports to absorb excess supply, crop prices can fall.

Moreover, the procurement process in India remains uneven (being largely operative for major crops like rice and wheat and is restricted to a few areas) and therefore the minimum support prices fail to efficiently act as a floor for crop prices. Last year, despite a good monsoon, oversupply of pulses led to a sharp drop in prices – below the MSPs – and consequently a fall in farm incomes. In such episodes, what makes matters worse is the relative inelasticity of demand of essential food items – demand does not adjust adequately to the fall in prices. Thus there is a net erosion in farmer income. Therefore, this year also, the impact of a good monsoon on rural incomes will depend on how MSPs and how the procurement process is beefed up in regions where it has been inadequate.

The Ifs and Buts:

Can procurement rise sharply?

The reach of public procurement remains limited in India and only one-third of the farmers are even aware of MSPs (as per the NSS Assessment Survey of Agricultural Households). Moreover, a substantial portion of agriculture produce is sold to private traders to whom small and marginal farmers are often indebted.

Apart from the reach and awareness of the procurement process, there are other issues that could limit the increase in crop procurement by the government. These include the lack of adequate storage facilities and logistics challenges, no standard policies on exporting surplus produce even in wheat and rice, and storage limits that discourage investments by private stakeholders.

One way forward is to increase the participation of private players in the procurement process. The government can engage private players for testing and assaying procured crops, warehousing and storage of stocks, and to finally market crops. There are a number of incentives that the government can provide to attract private players such as freeing the private players from stock limits and export restrictions, fixing import duties in a way that the landed price is not less than the domestic price, and giving benefits to the private players for investment in creation of supply chain infrastructure.

Box: Price compensation and its pitfalls – The Bhavantar Scheme

In Madhya Pradesh, the government pays the farmers the difference between the MSP and the market prices but does not procure the grains itself under the Bhavantar Scheme. This scheme is less distortionary than the normal procurement system and saves the government from the issues of procuring, storing and offloading crops. However, the structure of the scheme creates a classic case of moral hazard where traders have the incentive to give lower prices to the farmers – who being compensated by the government and usually eager to sell their produce – accept these lower prices. Other loopholes in the scheme include sale of stock below the fair quality as there is no grading under the scheme. Therefore, price compensation schemes like Bhavantar are not the best option forward without significant modifications.

The MSP challenge

Given the pressure faced by the government in a pre-election year and with major agriculture-heavy states also facing elections this year, it is clear that the government will choose a broad measure of cost to calculate the 1.5 times increase in MSPs so as to provide maximum benefit to the farmers.

To recall, in the latest budget, the government announced that it will raise MSPs by 1.5 times of the cost of production this year. The impact of this increase on prices and actual income realisations will depend on 1) what cost of production is considered? and 2) How much of the increase in MSPs translates into raising prices as the procurement process in not operative for most crops and in most regions. It is now a given that a broad cost of production measure (A2+FL) will be considered but we are uncertain on what percentage of crops will actually be bought at these prices if there is (as we mentioned) not a complementary increase in procurement efficiency.

3. Rural inflation has had a depressing effect on nominal wages

Inflation is usually associated to be a determinant of real wage growth. However, we find that rural inflation is also an important driver of nominal rural wage growth. Through a simple wage model (looking at the beta estimates of a linear regression – see Appendix) we find that rural inflation movements lead the changes in agriculture wages by 3 months. Rural inflation started declining at the start of 2017 dropping to 3% in May 2017 from 6.5% a year earlier and was followed by a decline in agricultural wages from July 2017 onwards. Extending this relationship, it is likely that rural agricultural wages could reverse some of its recent decline as rural inflation momentum has started picking up pace.

4. The MGNREGS effect has been declining

MGNREGS wages led to the increase in rural wage growth up to 2012-13 by setting a floor for many informal sector activities and by raising the opportunity costs for agricultural labourers. However, in recent years, MGNREGS wage growth has moderated from over 10% in 2013-14 to just 3% in 2018-19, leading to a decline in rural wage growth.

Our state level analysis shows that 7 out of 15 major states saw a less than 2% increase in MGNREGS wage growth in 2017-18. For 2018-19, the story is more mixed. Some states like Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Jharkhand and Bihar are expecting no increase in MGNREGS wages while others like Telangana, West Bengal, Odisha, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka are expected to see an increase between 3-6%. Therefore, the impact of MGNREGS wages on overall wage growth in the economy is difficult to ascertain. At best, the increase in some states could offset the fall in the others.

That said, it is also important to note that the importance of MREGA wages as a driver of rural wage growth has weakened. The person-days of employment generated by the MGNREGS programme has declined in 2017-18 and central government expenditure on MGNREGS as a share of total expenditure has also been coming down. The RBI study finds that MGNREGS wages do not have a statistically significant relationship with agricultural wages in recent times.

I. Exploring the factors determining rural wage growth

We carry a simple linear regression model with our dependent variable as nominal rural agricultural wage growth. The independent variables considered are rural inflation with a lag of 1 quarter, non-agri nominal wages, and construction wages. We have taken rural wage data from November 2014 to February 2018 from the RBI.

We take the Beta coefficients as a representation of the correlation between agricultural wage growth and our independent variables. We find a strong correlation between the below variables as per the beta estimates that are statistically significant as per the t-statistic and p-value.

| Agricultural Nominal Wages | Lag | |

| Beta Estimates | ||

| Rural Inflation (-3) | 0.99*** | 3 months |

| Non-Agri wages | 0.86*** | 0 |

| Construction wages | 0.92*** | 0 |

***significant at 1% levels of significance

II. Causality between farm and non-farm wages

To determine the relationship between farm and non-farm wages in the rural economy we carried out a Granger Causality Test. The lag length criteria analysis showed that lag length of 1 was optimum for both the variables. The results of the Granger Causality test showed that we can reject our null hypothesis that non-agri wages do not granger cause agri-wages. However, we accepted the null hypothesis that agri wages do not granger cause non-agri wages. This implies that the causation runs from non-farm wages to farm wages in rural India.

| Pair Wise Granger Causality Tests | |||

| Lags:1 | |||

| Null Hypothesis | Obs | F-statistic | Prob. |

| Non-Agri wages do not Granger cause Agri-wages | 51 | 18 | 0.0001 |

| Agri wages do not Granger cause Non-Agri Wages | 5 | 0.0298 |

Source- HDFC Bank’s Treasury Research Report

Disclaimer: This document has been prepared for your information only and does not constitute any offer/commitment to transact. Such an offer would be subject to contractual confirmations, satisfactory documentation and prevailing market conditions. Reasonable care has been taken to prepare this document. HDFC Bank and its employees do not accept any responsibility for action taken on the basis of this document

*Mr. Abheek Barua, Chief Economist, HDFC Bank. Mr. Barua tweets at @AbheekHDFCBank.