Summary: The 2024 Supreme Court judgment on Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) by a seven-judge bench highlights judicial delays and unresolved core issues surrounding minority educational institutions in India. Despite decades of deliberations and the landmark S. Azeez Basha ruling being overturned, the court refrained from conclusively deciding whether AMU qualifies as a minority institution under Article 30 of the Constitution. Instead, it laid down broad parameters for determining minority status, delegating the matter to a three-judge bench for further adjudication. This lack of resolution perpetuates uncertainty that has persisted for over 50 years, affecting the rights and policies of institutions established before the 2006 NCMEI Act amendments. The dissenting opinion of Justice Dipankar Datta underscored procedural and substantive deficiencies in handling this matter, reflecting broader systemic issues in judicial decision-making. This judgment also revisits concerns about whether institutions like AMU can implement reservation policies for specific minorities, a contentious issue given India’s cultural diversity and evolving socio-political context. The implications of such delays and non-decisions ripple through the educational and legal frameworks, causing operational challenges for affected institutions. While the court addressed procedural aspects, the lack of a definitive ruling continues to hinder clarity in law and policy-making, raising questions about judicial efficiency and accountability.

Page Contents

Let’s Begin

a) This article is based on a judgement by a 7-member bench of Supreme court dated 8-Nov-2024 in the case of Aligarh Muslim University (the AMU judgement 2024). The author gives various aspects related to this case. The author could complete this article only because the author can empathise with the position of Justice Dipankar Datta.

b) Refer to the link on official website of Supreme Court of India-:

https://api.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2006/9287/9287_2006_1_1501_57054_Judgement_08-Nov-2024.pdf

c) Labyrinth means a

a. complicated irregular network of passages or paths in which it is difficult to find one’s way.

b. There is a Greek mythological story to this word where a king kept a person into a Labyrinth of constriction where actually he wanted to put him in jail but could not do it officially.

c. This word is used to express negative sentiments labyrinth is a complicated or tortuous arrangement or state of things or events; a bewildering complex.

d) A reader may consider reading the Chronology of events to get himself acquainted with the background. It is slightly complex.

Why this article

a) First and foremost,

a. Minority Institution is eligible for all the aid from the State Governments.

b. A minority Institute is eligible for draft its own internal policies, procedures etc.,

c. Strictly speaking, reservation policy does not apply to Minority Institutions.

d. A corollary of clause (b) and (c) above, a minority institution is eligible for reserving seats based on caste or religion or culture or language.

b) The reader will be able to understand importance of an institution being classified as Minority Institution.

c) To highlight the (miserable) way this issue has been handled by judiciary in general and by the Supreme court in specific.

d) A separate and strongly dissenting judgement of Justice Dipankar Datta goes on to shows how this case was handled internally in specific and this subject in general which itself is equally disturbing.

e) The irony is that, even today, especially after:

a. much of the deliberations over a period of say 50 years in ‘n’ number of Supreme Court judgements, and

b. the AMU Judgement 2024, the law has not settled to determine:

c. whether AMU is a minority Institution or not

d. sufficiently clear parameters to determine whether an institution is a minority institution or not.

f) The AMU judgement 2024 nullified the judgement S Azeez Basha which had decided the core question(s) (which held the field for 50 years) without itself answering those core question(s) on either side but has laid down parameters (Indica) based on which a 3-member bench will decide whether AMU is “Minority Institution” under article 30.

g) India itself is a country which has a diversity in every aspect which even whole of the Europe does not have. Today in 2024, it significantly stands changed as compared to 1967 (Approximately 56 years) on the touchstone of every imaginable parameter.

h) Article 30 of the Constitution is there on rulebook for 75 years. Law also recognises the concept namely “Temporal Reasonableness”, which means that something which was earlier reasonable is no longer so or ceases to be so with the passage of time”.

To give a classic example of Temporal Reasonableness,

As of today, “Doctor assisted death” is a criminal offence in UK but on 29-Nov-2024, the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill 2024-2025 got initial approval.

Tomorrow if it becomes law, something which is a criminal offence today will not be even a civil wrong. “Doctor assisted death” is different from euthanasia.

“Let’s be clear, we’re not talking about a choice between life or death, we are talking about giving dying people a choice about how to die,” the bill’s main sponsor, Kim Leadbeater, said as she presented the bill to a packed chamber.

Refer-: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/CBP-10123/

Scope

a) At the outset, the issue of classification of an institution being either minority or non-minority pertains to those formed before 2006. But most of the significant Institutions are indeed formed before the year 2006.

a. Before discussing anything on the subject, it is relevant to note the provisions of the NCMEI Act[1] enacted in 2004 to constitute a National Commission for minority educational institutions and to provide for matters connected or incidental to it.

b. Section 10 of the NCMEI Act was amended in 2006. The amended provision prescribed a procedure for the establishment of a minority educational institution.

c. Thus, there can be no ambiguity about the minority status of educational institutions established after the enactment of NCMEI (Amendment) Act 2006.

d. But being a prospective amendment, it can-not be applied for institutions which were established before the 2006 Amendment.

b. Refer a few illustrations of institutions formed under an Act of Parliament or Legislative Assembly (i.e. by State Law)

| Sr. | Name of the Act | Governs the functioning of |

| a | The Banaras Hindu University Act, 1915 | Banaras Hindu University. |

| b | The Aligarh Muslim University Act, 1920: | Aligarh Muslim University. |

| c | Visva-Bharati Act, 1951 | Visva-Bharati University, founded by Rabindranath Tagore. |

| d | Dakshina Bharat Hindi Prachar Sabha Act, 1964 | institution focused on promoting the Hindi language in South India |

| e | The Central Sanskrit University Act, 1970 | the Central Sanskrit University |

| f | Sree Chitra Tirunal Institute for Medical Sciences &Technology, Trivandrum, Act, 1980: | which is dedicated to medical sciences and technology, at Trivandrum |

| g | Kalakshetra Foundation Act, 1993 | Governs the Kalakshetra Foundation, an arts & cultural academy in Chennai. |

| h | The Chhattisgarh Niji Kshetra Vishwavidyalaya (Sthapana Aur Viniyaman) Adhiniyam, 2002: | private universities in Chhattisgarh |

How the Amendment addressed the problem?

c) The National Commission for Minority Educational Institutions (Amendment) Act, 2010 introduced several key changes to the National Commission for Minority Educational Institutions Act, 2004:

i. Expanded Powers: The amendment enhanced the powers of the Commission to investigate matters related to the deprivation of educational rights of minorities. This includes the authority to call for information and conduct inquiries.

ii. Minority Status Decisions: The Commission was given the power to decide on the minority status of educational institutions, which was previously handled by the Competent Authority.

iii. Appeals: The amendment allowed for appeals against the orders of the Competent Authority to be made to the Commission.

iv. No Objection Certificates: The process for granting no objection certificates for the establishment of minority educational institutions was streamlined.

v. Affiliation Rights: Minority educational institutions were given the right to seek affiliation with any university of their choice, subject to the rules of the affiliating university.

d) Thus, this judgement and this article addresses the problem of Institutions formed before 2006.

Chronology of Events

| Year | Citation | Particulars |

| 1915 | BHU Act, 1915 | The Banaras Hindu University Act, 1915 came into force in British regime |

| 1920 | AMU Act 1920 | The Aligarh Muslim University Act, 1920. This act was amended in 1951 and in 1965 |

| 1950 | The Constitution | The constitution of India came into force w.e.f. 26-Jan-1950 |

| 1956 | The UGC Act, 1956 | the University Grants Commission Act, 1956. An Act to make provision for the co-ordination and determination of standards in Universities and for that purpose, to establish a University Grants Commission. |

| 1967 | Azeez Basha | A judgement of 5-member bench of Supreme court dealing with amendments to the AMU Act, 1920. It held that AMU is not a minority Institute. |

| Nothing happened for 20 years. | ||

| 1981 | AMU Amend-ment Act | To nullify the impact of decision of Azeez Basha |

| 1981 | Rehmania | Rehmania was a 2-member bench of Supreme Court, and it referred the matter to a larger bench. At the time of referring permission was granted that this matter be quoted before CJI as urgent for “listing” and further action. |

| Nothing happened for 20 years. | ||

| 2002 | TMA Pai | An 11-member bench was coined to precisely answer the core question relating to Minority institutions and mattes thereto. But it did not answer the main question. The parameters laid down were so broad that every high court started interpreting it in its own manner. |

| 2003 | Islamic Academy | In this case, 5-member bench was coined to find correct ratio of TMA Pai which itself proved to be futile. |

| 2005 | P A Inamdar | Finally in this case, Supreme Court resolved 5 questions and to put curtains of cohesively reading the issue of ratio of TMA Pai read with Islamic Academy . But again did not answer the question of minority status. |

| 2006 | AMU vs Malay Shukla – | The short basic issue in all these appeals is whether the Aligarh Muslim University is a minority Institution. The point arises because suddenly some eighty-five years after incorporation, they chose for the first time to reserve a Muslim quota, by way of a 50% reservation of post-graduate course seats meant for qualified MBBS doctors.

[Allahabad High Court – also in appeal in the AMU Judgement] |

| Nothing happened for 13 years. (This time Judiciary acted by 7 years earlier as compared to its precedence of 20 years each. | ||

| 2019 | a three-Judge Bench in AMU v Malay Shukla | The three-Judge Bench then referred the matter to a seven-Judge Bench. When this matter was taken up for hearing, the Union of India sought to withdraw its appeal against the decision of the Division Bench of the Allahabad High Court Civil Appeal No. 2318 of 2006, Supreme Court of India This Court is competent to hear the present case even if the Union of India was permitted to withdraw its appeal because the other appellants continue to press their case. |

| This time Supreme Court found time to take up the matter and the judgement is out in 5 years…!!! | ||

| 2024 | AMU Judgement | Again, issuing guidelines without deciding whether AMU is a minority institution or not. |

Background and Objective-:

a) Despite a 7-member bench, Supreme Court has in the case of AMU[2] has practically not answered the main question as to “whether AMU is a Minority Educational Institution or not”.

b) Justice delayed is justice denied. In this case, we are not even considering correctness or otherwise of the decision because there is no decision….!!!. This is an even worser a situation.

c) Supreme Court has provided broad guidelines or parameters for determining whether a particular educational institution is a minority institution or not. This issue is languishing for more than 50 years.

d) Knowingly or otherwise, it has also decided upon questions which otherwise were not before the bench. There is a significant threat that it may (rather will) cause significant harm in future.

e) The Author tried to bring out the gravity of the above phenomena. The author has, per se, not entered into the core issue but has restricted itself with the process or lacunas thereof.

f) The worser part is similar phenomenon has happened in past broadly on the same subject matter.

g) Lastly, and most importantly, Judges are there to decide upon matters referred to them. Generally, in such cases, the Court is expected:

a. to peruse the facts

b. lay down framework of law applicable and

c. apply the said framework to the facts of the case under consideration to reach to a conclusion.

h) In simple terms, the Apex Court should have practiced what it preaches…

Ramifications

i) What happens in such cases has more aptly been explained in paragraph (c) under the heading History Repeats below.

j) A more specific, direct and visible impact is whether such institutions can have their own reservation policy for specified class of minority based on linguistic / cultural basis.

k) A decision of any court always has a retrospective effect because a court never makes the law, it only interprets the law. In India, only Supreme court (not even High court) has power to rule that a particular judgement will have a prospective effect.

l) Whenever any old issue is decided, it poses significant problems in giving effect to the decision because with substantial lapse of time, the whole environment in which the parties work stands changed.

a. Firstly, a number of cases are tagged along-with such a matter which are expected to be decided in view of such a constitution bench decision.

b. Secondly, a great deal of uncertainty looms over without any idea as to when it will be settled, what will be the outcome etc

c. Thirdly, and more worry some portion is that it has laid down many other ratios which may (rather will) cause significant harm in future.

Citation of the case-:

Forum-: Supreme Court of India

Constitution bench-: 7 members

Neutral Citation-: 2024 INSC 856

| Majority Opinion – Unanimous by all four | Minority Opinion – each separate |

| 1) Dr Dhananjaya Y

Chandrachud, CJI 2) Sanjiv Khanna 3) J B Pardiwalla 4) Manoj Misra |

5) Surya Kant 6) Satish Chandra Sharma 7) Dipankar Dutta

|

Questions posed, and Answers Given-:

Following are the questions / issues framed to be answered by the majority judgement.

The judgement is by majority of 4:3.

The degree or quantum of Dissent of

Justice Surya Kant is much less and thereby much closer to majority opinion

Justice Satish Sharma is a bit more away than Justice Surya Kant

Justice Dipankar Datta is completely away from all above

| Particulars | Majority Opinion | Surya Kant | Satish Sharma | Dipankar Datta |

| Whether the methodology and decision of smaller bench referring to 7 members was a valid action | ||||

| First reference | Yes | No | No | No |

| Second reference | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Whether this action can act as a precedence | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Whether the question as to whether AMU is a “minority institute” under article 30 is answered ? If yes, | No | No | No | Yes |

| If No, what is the outcome? – Parameters were defined | N.A. | |||

| If Yes, what is the outcome ? whether AMU is a “minority institute” | No. | |||

| How the phrase “establish and administer” in Article 30 be read i.e. whether | ||||

| only establishment by minority group

is sufficient or |

Yes | No | No | No |

| establishment and administration

both should be with minority group |

No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Parameters laid down and matter referred to 3-member bench to decide considering facts of the case. | Yes | Yes | Yes | N.A. |

| Whether the judgement Azeez Basha which required a dual test that the institute must be established and administered by minority is nullified to that extent ? | Yes | No | No | No |

| Whether the Institutions established in pre-independence era are eligible for benefit under article 30 | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Whether its mere conversion into University will debar the institute from benefit of article 30 | No | No | No |

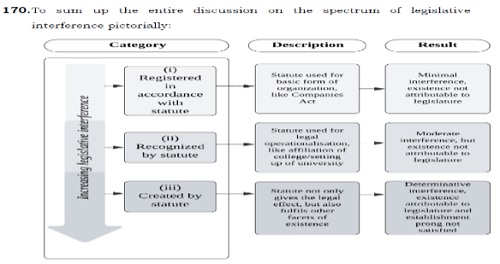

Regarding Establishment and Administration, Justice Surya Kant, in his separate opinion at para 170 has observed as follows

Internal Dis-connect

a) CJI was to retire on 10-Nov-2024, prima facie ample time was available.

b) Hearing on appeals and petitions commenced on 9-Jan-2024

c) It was spread over 8 days till it was reserved on 1st Feb-2024

d) First draft authored by CJI was received on 25-Oct-2024 running into 117 pages.

e) Second draft authored by CJI was received

f) The effect of the revised draft opinion of the CJI is the defenestration of the view taken in Azeez Basha (supra) that Aligarh Muslim University5 is not a minority institution. Such a view has stood its ground for the last more than 50 (fifty) years. It is the only decision of this Court where Article 30(1) was considered and law laid down keeping establishment and administration of a pre- independence era university in perspective as distinguished from schools and colleges, which have been the subject matter of other Constitution Bench decisions.

g) On 2-Nov-2024, came another few pages from the office of the CJI containing corrections effected in quite a few of the paragraphs of the revised draft opinion in track changing mode with paragraph 72 being altogether deleted.

h) Separate judgements of dissenting judges (irrespective of nature, character) was received 6-Nov-2024.

i) There was no discussion to facilitate the following being a true democratic spirit to build up a consensus.

-

- common venue for a purposeful.

- effective dialogue.

- freely express points of view.

- an attempt to share thoughts.

- to exchange opinions.

- a ‘give’ and ‘take’ of ideas.

j) All the judges for a little while on 7th November, 2024 where it was revealed that the opinion of CJI had the concurrence of 3 (three) Judges to make a majority of 4.

k) It indicates that in such a case, what other 3 judges think is irrelevant because it will not have any effect on the outcome of the judgement.

l) Azeez Basha a judicial verdict more than half a century old on the status of AMU vis-à-vis minority rights, has a strong foundational basis and is anchored in robust legal reasoning.

m) But if a bench of 2 (two) learned Judges concludes that an earlier judgment of a bench of 3 (three) learned Judges is so very incorrect that in no circumstances can it be followed, the proper course for it to adopt is to refer the matter before it to a bench of 3 (three) learned Judges setting out the reasons why it could not agree with the earlier judgment and if the bench of 3 (three) learned Judges also comes to the conclusion that the earlier judgment of a bench of 3 (three) learned Judges is incorrect, then a reference could be made to a bench of 5 (five) learned Judges.

Facts of the case-:

AMU traces its origins to its institutional predecessor, Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental (MAO) College was established in Aligarh. The college was a teaching institution affiliated to the Calcutta University at first and subsequently to the Allahabad University College which was established on 08th January 1877.

The establishment of MAO College was spearheaded by late Sir Syed Ahmed Khan (Sir Syed) a national leader who envisioned the idea of a modern and Western educational institution for the Muslim community, distinct from the traditional madrasas, which otherwise prevailed. There is no contest to the fact that that MAO College was established specifically for the educational advancement of the Muslims; it is what comes thereafter which is the point of contention and calls for being noticed, to the extent relevant, and addressed.

Parallelly, the movement for a Hindu university which took shape with the establishment of the Banaras Hindu University through a similar statute, viz. the Banaras Hindu University Act, 1915.

This subject itself has a long-checkered history. The imperial legislature was passed the Aligarh Muslim University Act 1920 which came into effect from 1st December, 1920, see Gazette of India 1920, Pt. I. page 2213.

A Constitution Bench dismissed the writ petitions in Azeez Basha in 1967 the challenge on the ground of violation of Article 30(1) was rejected on the following grounds:

a. The phrase “establish and administer” in Article 30(1) must be read conjunctively. Religious minorities have the right to administer those educational institutions which they established. Religious minorities do not have the right to administer educational institutions which were not established by them, even if they were administering them for some reason before the commencement of the Constitution;

[This portion has been over-ruled by the 2024 judgement which is the subject under consideration]

b. The word “establish” in Article 30(1) means “to bring into existence”;

c. AMU was not established by the Muslim minority for the following reasons:

i. AMU was brought into existence by the AMU Act, which was enacted by Parliament in 1920. Section 6 of the AMU Act provides that the degrees conferred to persons by the University would be recognised by the government. This provision indicates that AMU was established by the Government of India because the Muslim minority could not have insisted that the degrees conferred by a university established by it ought to be recognized by the Government. The AMU Act may have been passed as a result of the efforts of the Muslim community but that does not mean that AMU was established by them;

ii. The conversion of the College to the University was not by the Muslim minority but by virtue of the 1920 Act; and

iii. Section 4 of the AMU Act by which the MAO College and the Muslim University Association were dissolved, and the properties, rights and liabilities in the societies were vested in AMU shows that the previous bodies legally ceased to exist;

d. Since the Muslim community did not establish AMU, it cannot claim a right to administer it under Article 30(1). Thus, any amendment to the AMU Act would not be ultra vires Article 30 of the Constitution;

e. The argument that the administration of the University vested in the Muslim community though it was not established by them was rejected. The administration of AMU did not vest in the Muslim minority under the AMU Act for the following reasons:

i. Although all the members of the Court (which was the supreme governing body in terms of Section 23 of the AMU Act) were required to be Muslims, the electorate (which elected the members of the Court) did not comprise exclusively of Muslims;

ii. Other authorities of AMU such as the Executive Council and the Academic Council were tasked with the administration of the University and were given significant powers. The members of these bodies were not required to be Muslims;

iii. The Governor General (who was the Lord Rector) was also entrusted with certain “overriding” powers concerning the administration of the University. The Governor General was not required to be a Muslim. In terms of Section 28(3), the Governor General had overriding powers to amend or repeal the Statutes. The Governor General possessed similar powers with respect to amending or repealing Ordinances. In terms of Section 40, the Governor General had the power to remove any difficulty in the establishment of the University; and

iv. The Visiting Board which consisted of the Governor of the United Provinces, the members of the Executive Council and Ministers were not necessarily required to be Muslims;

f. The term “establish and maintain” in Article 26 must be read conjunctively, like the phrase “establish and administer” in Article 30. Assuming that educational institutions fall within the ambit of Article 26, the Muslim community does not have the right to maintain AMU because it did not establish it;

[The portion “The term “establish and maintain” in Article 26 must be read conjunctively, like the phrase “establish and administer” in Article 30” has been over-ruled by 2024 judgement which is subject matter of this article.]

and

g. The impugned amendments do not violate Articles 14, 19, 25, 29 and 31.

Issues before Court, in general

In 2002, an eleven-Judge Bench of this Court in TMA Pai,

Following were the questions framed for the bench which properly covered all the issues. But the Court did not answer the core question.

These questions will enable reader to properly appreciate the coverage of the issue

Q.1. What is the meaning and content of the expression “minorities” in Article 30 of the Constitution of India?

Q.2. What is meant by the expression “religion” in Article 30(1)?

Can the followers of a section or denomination of a particular religion claim protection under Article 30(1) on the basis that they constitute a minority in the State, even though the followers of that religion are in majority in that State?

Q.3(a) What are the indicia for treating an educational institution as a minority educational institution? Would an institution be regarded as a minority educational institution because it was established by a person(s) belonging to a religious or linguistic minority or its being administered by a person(s) belonging to a religious or linguistic minority?

This question was not be answered by this Bench and was referred to a regular bench. Even the regular bench did not answer it

[High-lighted Portion – that of Author]

Q.3(b) To what extent can professional education be treated as a matter coming under minorities rights under Article 30?

Q.4 Whether the admission of students to minority educational institution, whether aided or unaided, can be regulated by the State Government or by the University to which the institution is affiliated?

Q5(a) Whether the minority’s rights to establish and administer educational institutions of their choice will include the procedure and method of admission and selection of students?

Q.5(b) Whether the minority institutions’ right of admission of students and to lay down procedure and method of admission, if any, would be affected in any way by the receipt of State aid?

Q.6(a) Where can a minority institution be operationally located? Where a religious or linguistic minority in State ‘A” establishes an educational institution in the said State, can such educational institution grant preferential admission/reservations and other benefits to members of the religious/linguistic group from other States where they are non-minorities?

Q.6(b) Whether it would be correct to say that only the members of that minority residing in State ‘A’ will be treated as the members of the minority vis–vis such institution?

Q.7 Whether the member of a linguistic non-minority in one State can establish a trust/society in another State and claim minority status in that State?

Q.8 Whether the ratio laid down by this Court in the St. Stephen’s case (St. Stephen’s College v. University of Delhi is correct? If no, what order?

Q.9 Whether the decision of this Court in Unni Krishnan J.P. v. State of A.P. (except where it holds that primary education is a fundamental right) and the scheme framed thereunder required reconsideration/modification and if yes, what?

Q.10 Whether the non-minorities have the right to establish and administer educational institution under Article 21 and 29(1) read with Articles 14 and 15(1), in the same manner and to the same extent as minority institutions? and

Q.11 What is the meaning of the expressions “Education” and “Educational Institutions” in various provisions of the Constitution? Is the right to establish and administer educational institutions guaranteed under the Constitution?

——— —————— —————— —————- ————-

Some Gossip before we close.

November 8, 2024, was a Friday last working day (technically he was set to retire on November 10, 2024 Sunday) for Dr. Dhananjaya Chandrachud (CJI as he was then) and the farewell ceremony took place on very same day.

In the farewell, he addressed Justice Sanjiv Khanna as CJI-Designate who took the oath on 11th November 2024.

Perhaps Dr. Chandrachud had kept the intermittent 2 days to address any contingency and rightly so because a CJI is has to dis-charge multiple roles in addition to act as a judge,

Having discussed various issues, following is the law of land as of today.

F. Conclusion

160. In view of the above discussion, the following are our conclusions:

a. The reference in Anjuman-e-Rahmaniya (supra) of the correctness of the decision in Azeez Basha (supra) was valid. The reference was within the parameters laid down in Central Board of Dawoodi Bohra Community (supra);

b. Article 30(1) can be classified as both an anti-discrimination provision and a special rights provision. A legislation or an executive action which discriminates against religious or linguistic minorities in establishing or administering educational institutions is ultra vires Article 30(1). This is the anti-discrimination reading of the provision. Additionally, a linguistic or religious minority which has established an educational institution receives the guarantee of greater autonomy in administration. This is the ‘special rights’ reading of the provision;

c. Religious or linguistic minorities must prove that they established the educational institution for the community to be a minority educational institution for the purposes of Article 30(1);

d. The right guaranteed by Article 30(1) is applicable to universities established before the commencement of the Constitution;

e. The right under Article 30(1) is guaranteed to minorities as defined upon the commencement of the Constitution. A different right-bearing group cannot be identified for institutions established before the adoption of the Constitution;

f. The incorporation of the University would not ipso facto lead to surrendering of the minority character of the institution. The circumstances surrounding the conversion of a teaching college to a teaching university must be viewed to identify if the minority character of the institution was surrendered upon the conversion. The Court may on a holistic reading of the statutory provisions relating to the administrative set-up of the educational institution deduce if the minority character or the purpose of establishment was relinquished upon incorporation; and

g. The following are the factors which must be used to determine if a minority ‘established’ an educational institution:

i. The indicia of ideation, purpose and implementation must be satisfied. First, the idea for establishing an educational institution must have stemmed from a person or group belonging to the minority community; second, the educational institution must be established predominantly for the benefit of the minority community; and third, steps for the implementation of the idea must have been taken by the member(s) of the minority community; and

ii. The administrative-set up of the educational institution must elucidate and affirm (I) the minority character of the educational institution; and (II) that it was established to protect and promote the interests of the minority community.

161. The view taken in Azeez Basha (supra) that an educational institution is not established by a minority if it derives its legal character through a statute, is overruled. The questions referred are answered in the above terms. The question of whether AMU is a minority educational institution must be decided based on the principles laid down in this judgment. The papers of this batch of cases shall be placed before the regular bench for deciding whether AMU is a minority educational institution and for the adjudication of the appeal from the decision of the Allahabad High Court in Malay Shukla (supra) after receiving instructions from the Chief Justice of India on the administrative side.

162. The reference is disposed of in the above terms.

163. Pending applications, if any, stand disposed of.

[Dr Dhananjaya Y Chandrachud], CJI

[Sanjiv Khanna]

[J B Pardiwala]

[Manoj Misra]

New Delhi;

November 8, 2024

Notes:

[1] The Nation Commission for Minority Educational Institution Act 2004

[2] Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) dated 08-Nov-2024