INTRODUCTION

India is home to an impressive 1.3 billion people, making it the world’s second most populated nation. Despite this, income tax plays just a minor role in India, with only approximately 3% of the population actually paying it. The limited role of personal income tax in India has always been a topic of debate. While some people feel that it provides a much needed relief to the taxpayers, others feel that it restricts the government’s ability to generate revenues and fund public welfare programs. Before reaching a judgment on the topic, it is crucial to consider the benefits and drawbacks of India’s personal income tax’s restricted function. Personal income tax in India plays a very little role, which is good news for taxpayers since it means less money is collected from each individual. It has also resulted in an increase in the disposable income of individuals, allowing them to spend more on essential items. On the other hand, the limited role of personal income tax also means that the government is unable to generate sufficient funds to finance essential public welfare programs. It is thus essential to weigh the pros and cons of the limited role of personal income tax in India in order to determine whether it is beneficial or detrimental to the country. This article examines the personal tax structure in India and its impact on increasing inequality and poverty and changes that can be brought to the tax structure.

Also discussed is whether or not it makes sense for emerging nations like India to forego using personal income tax for redistributive goals. The first is that inequality in India has not been mitigated by the personal income tax.[1] Second, pretending to have a progressive personal income tax system does not come without its own set of costs. Thirdly, using taxes for distribution causes opportunity costs. The essay also examines the question of whether or not using the income tax for such objectives is a good idea.

ARTICLE REVIEW

In most countries, individual income taxes get the greatest attention and are the subject of the most debate. In 1950–51, 21 percent of the taxes collected in India came from individuals’ own income. Its market share had dropped to around 5% by 1986–1987. “There does not seem to have been a decrease in interest among economists, attorneys, and accountants in the structure of personal income tax, despite the fact that the percentage of personal income tax has decreased.” In reality, the amount of time spent on this issue is excessively high given the little percentage of tax revenue that comes from individual income taxes.[2]

The base and the rate schedule are the backbone of every system for taxing individual income. It may be possible to achieve a desired level of revenue with a lower average tax rate if the base is expanded. The base and the rate structure also interact closely with one another. It seems to reason that a higher marginal tax rate would discourage people from working to acquire funds for leisure, which would make leisurely spending look more appealing. When people’s effective tax rate is greater, they are more likely to try to hide their income. Numerous key models have been developed to explain the relationship between the base and the rate schedule. “works such as Mirrlees (1971), Sheshinski (1972), Atkinson (1973), among others, and some of the issues pertaining to evasion have been highlighted in works by Allingham and Sandmo (1972), Srinivasan (1973), and Nayak (1978).

Taxation was utilized as a tool in the planned economy model established since independence to curb private consumption and shift resources to the government to fund massive public investment projects meant to stimulate economic development. Income and wealth disparities were also addressed via progressive taxation, which gained popularity in the 1970s. In the middle of the 1980s, people started paying attention to the difficulties that the indirect tax system, which was not unified and was complicated, caused due to the plethora of levies and the ripple effects of those levies. Modified value added tax was implemented as a first step in reforming the tax system (MODVAT). As a result of the structural adjustment program implemented after the economic crisis of 1991, tax changes were prioritized in the early 1990s. Since then, there has been a constant stream of improvements to the tax system.[3]

India continues to confront two of its greatest difficulties in the form of poverty and inequality. Higher economic growth was seen after the macro-economic changes of 1991, although it was concentrated in and around major cities (Chandan & Shankar, 2012). Although the country has gained international recognition for its recent economic development and improvements in a number of key socioeconomic metrics, poverty and inequality continue to be serious issues. In the previous 10 years, India has made strides in the areas of road building, electricity generation, telecommunications, and general infrastructure development. The nation has not achieved enough progress, however, in redistribution of resources and the improvement of people’s living conditions at the bottom of the economic ladder. The lockdown caused by Covid-19 in 2020 is a testament to the disparity in India, since it affected poor and migrant workers the most. There has been an increase in rural suffering, unemployment, poverty, starvation, and malnutrition after the end of the lockdown.[4]

The reality is that India has not been successful in considerably reducing inequality. Indeed, a growing body of research at the national and international levels confirms a pattern of increasing inequality. Dang & Lanjouw (2018), for instance, calculated that inequality in India increased between 1983 and 2012. A recalculation of the Gini coefficient shows a rise in inequality from 0.344 in 2004 to 0.357 in 2012, as reported by the World Bank (2020). Moreover, India’s wealth is highly concentrated, with the top 1 percent owning more than half of the country’s total wealth. Also, there exist economic gaps across different demographics, with the poorest state having a median income that is nine times lower than that of the richest. There is a lot of inequality between different religions or social classes as well. The Adivasi and Dalit communities, for instance, have the lowest rates of socioeconomic mobility and the greatest rates of chronic poverty in India (Balcazar et al., 2016)

Even for emerging nations like India, this is a pressing concern. “However, previous to the epidemic, most of the discussion surrounding India’s tax system centered on the indirect tax system, including arguments before and after the implementation of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) in July 2017 and the fall in the corporate tax rate in September 2019. Income taxation in the nation, on the other hand, has been studied far less extensively. It is generally agreed that individual income taxes have the potential to be among the most progressive instruments of tax policy, and hence may play a substantial role in effecting redistribution of income from the rich to the poor.” This function is becoming more crucial for India as evidence of growing inequality in the nation mounts. A staggering 55 percent of India’s GDP in 2016 was earned by the richest 1 percent of its citizens, making India one of the world’s most unequal nations, according to the 2018 World Inequality Report.[5]

EXISTING TAX SCHEDULE

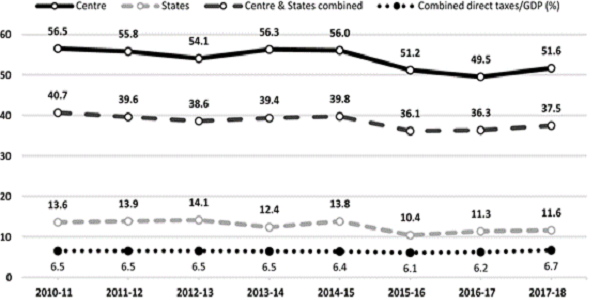

In order to understand how personal income taxes in India fit into the larger context of the Indian tax system in recent years, we may refer to Figure 1 and Table 1. More than half of the combined tax income of the federal and state governments in India come from indirect taxes, while direct taxes have contributed less than two-fifths in recent years (Fig. 1). Income taxation authority in India is centrally concentrated due to the country’s federal tax system. As a result, whereas direct taxes provide just around 12% of state governments’ tax collections, they contribute more than 50% of the federal government’s tax revenues. Personal income taxes constitute a significant part of the federal government’s direct tax collection. They are responsible for around 20% of the central government’s direct tax revenue and 10% of the government’s overall tax revenue (Table 1). While personal income taxes have contributed between 12 and 14% of total federal and state tax receipts from 2011-12 through 2017-18, this is a very small portion. As a result, personal income taxes though a percentage of GDP have hovered at 1.9% to 2.5% throughout this time period, even as the total tax-GDP ratio hovered around 16%-18%.[6]

“Share of Direct Taxes in total taxes of the Centre and State and the overall direct tax/GDP ratio in India (%) Source Authors calculations based on RBI database

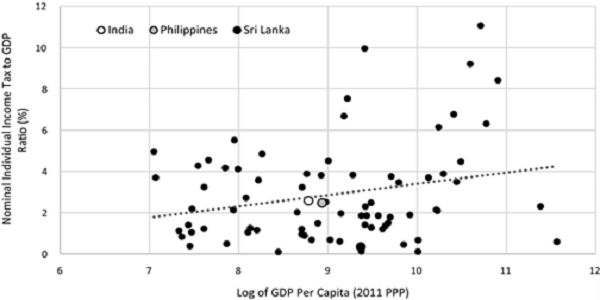

Cross-country income tax-to-GDP ratio against per capita GDP (2011 PPP), 2017. Source Authors’ calculations from Government Financial Statistics (GFS) and World Bank Database (WBD) data

ANALYSIS”

Horizontal equity and vertical equity form the basis of the contemporary taxation system. People with equal income or wealth should pay the same amount of tax, a principle known as horizontal equality, while those with more wealth or income should pay a higher rate of tax, vertical equity. These general tenets are sometimes referred to as the Ability to Pay basis of taxes. Those tax systems that adhere to these criteria are called progressive, while those that do not are called regressive.

Income-based tax brackets are the most tangible example of the ‘capacity to pay’ concept in action. The assumption that wages below a specific level are too low to be taxed is implicit in the fact that income tax is often applied only to those with earnings over that threshold. In addition, the percentage of taxable income often rises with increasing earnings. It is clear from table 1 that this is the situation in India.

Table 1: Rates of personal Income Tax (Financial Year 2018-19)

| Annual Income | Tax Rate (in%) |

| less than Rs. 2,50,000 | – |

| Rs. 2, 20,001 | 5 |

| Rs. 5,00,000 | 20 |

| Above Rs. 10,01, 001 | 30 |

Source: The Financial Bill, 2018, Government of India

As a result of these variations in rates, both the total amount and percentage of income going toward taxes increases as one’s income climbs. Income tax as a proportion of total income is shown in Graph 1.

The effective tax rate, or the amount of tax paid as a percentage of income, is shown to increase when income is increased in the graph. But what stands out is that the effective tax rate rises precipitously at lower earnings and then levels out at higher ones. If a taxpayer’s yearly income doubles from Rs. 10 lakhs to Rs. 20 lakhs, their effective tax rate will rise from 11% to 20%. However, if the same taxpayer saw a doubling of their yearly income from Rs. 1 crore to Rs. 1.5 crore, their effective tax rate will rise by just 0.3%, from 28% to 29%.

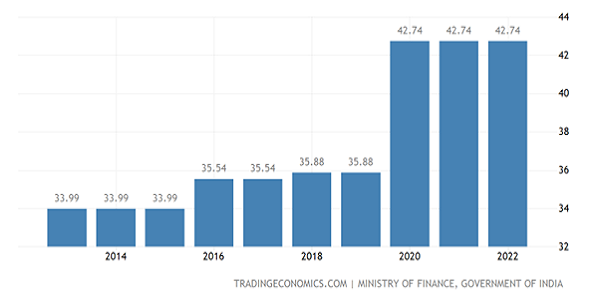

The Personal Income Tax Rate in India is a tax levied on several forms of personal income, including wages, retirement benefits, interest, and dividends. Specifically, we utilize the Top Marginal Tax Rate for people, which accounts for the standard deduction plus any applicable surcharges or additional taxes based on the cost of health care and/or education. The Indian government relies heavily on the proceeds from the Individual Income Tax Rate.

From 2004 to 2022, India’s Personal Income Tax Rate ranged from a high of 42.74 percent in 2020 to a low of 30 percent in 2005, with an average rate of 33.84 percent over that time period. The most recent data for India Personal Income Tax Rate (including data for previous years) can be found in January 2023.[7]

CONCLUSION

CONCLUSION

The share of GDP covered by personal income taxes is quite small, at 2.5%. Over forty percent of tax assessees pay no taxes, and fewer than six percent of adults pay taxes based on income. This aspect itself adds to the progressive nature of income taxes by concentrating tax revenue in the hands of a few. Nonetheless, owing to the small size of the taxes collected, this high degree of progressivity does not convert into a substantial redistributive impact. The redistributive impact on the taxpaying population as a whole is minimal, and much less on the working-age population. More persons will be subject to income taxation under a reduced exemption level, but their little contributions will not significantly change the amount of money collected through taxes. Given India’s present economic growth level and the size of the country’s informal sector, there are constraints on the country’s ability to widen its income tax net.

Benefits of redistribution are hard to examine without first establishing the proper function of government and the extent to which it has been successful in that role. It is equally difficult (and frequently not very helpful) to distinguish the quantity of resources available to the government, the tax system that provides those resources, and the efficiency with which the government utilizes the resources when assessing the redistributive function of taxes.

Notes

[1] Bird, R. M., & Zolt, E. M. (n.d.). REDISTRIBUTION VIA TAXATION: THE LIMITED ROLE OF THE PERSONAL INCOME TAX IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES. UCLA Law Review. https://www.uclalawreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/39_52UCLALRev16272004-2005.pdf

[2] Nayak, P. B., & Paul, S. (n.d.). Personal Income Tax in India: Alternative Structures and Their Redistributive Effects. Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 24, No. 50.” https://www.jstor.org/stable/4395708

[3] Pattnaik, R.K., Raj, D. S., & Chander, J. (n.d.). Empirical Fiscal Research In India: A Survey –RBI. https://m.rbi.org.in/scripts/bs_viewcontent.aspx?Id=1990

[4] “Kundu, S. (2022, April). FISCAL POLICIES AND THEIR IMPACT ON INCOME DISTRIBUTION IN INDIA*.” https://repec.tulane.edu/RePEc/ceq/ceq120.pdf

[5] “Datt, G., Ray, R. & Teh, C. Progressivity and redistributive effects of income taxes: evidence from India. Empir Econ 63, 141–178 (2022).” https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-021-02144-x

[6] Income Tax Department Time Series Data Financial Year 2000-01 to 2018-19. (n.d.). Income Tax Department. Retrieved January 28, 2023, from https://incometaxindia.gov.in/Documents/Direct%20Tax%20Data/IT-Department-Time-Series-Data-FY-2000-01-to-2018-19.pdf

[7] “India Personal Income Tax Rate – 2022 Data – 2023 Forecast – 2004-2021 Historical. (n.d.). Trading Economics. Retrieved January 28, 2023,” from https://tradingeconomics.com/india/personal-income-tax-rate

***

Panya Sethi

4th Year Law Student, Symbiosis Law School, Noida