Navigating Through a PMI Process | An Account of PwC’s M&;A Integration Survey (2023), McKinsey’s Intelligence and The Daimler-Chrysler Merger (1998)

Summary: In 1707, the Acts of Union created Great Britain, leading to significant global colonization. This historical event parallels today’s corporate landscape, where mergers and acquisitions (M&As) aim to harness mutual benefits. Despite their potential, a staggering 70-90% of M&As fail due to inadequate integration and communication. Successful Post-Merger Integration (PMI) is crucial, requiring meticulous planning that begins before the merger and continues through the transition phase. Each merger is unique, demanding tailored integration strategies that respect the cultures and operations of both companies. Key elements of a successful PMI include identifying value sources, setting synergy targets, and focusing on organizational integration. Furthermore, retaining talent and ensuring leaders are engaged in the integration process greatly influence outcomes. Successful integrations often prioritize Human Resources, Finance, and Information Technology, recognizing the importance of aligning these functions. However, overlooking broader aspects like culture and communication can lead to failures. The case study of Daimler-Chrysler illustrates the complexities of M&A; while initially promising, the merger faltered due to cultural clashes and market challenges. Understanding and implementing effective PMI strategies can enhance the chances of M&A success, fostering a unified organization capable of delivering shareholder value.

The Art of Integration

It’s the year 1707, and the English and Scottish parliaments vote upon what we now know as ‘The Acts of Union’ to form the Great Britain. The success of this alliance can perhaps be witnessed by the fact that this unified front later colonizes about 56 sovereign countries of today. Unified borders, unified parliaments, and a unified central administration acted to form a unified community.

This instance from the past can be seen rampantly in the corporate world of today. Mergers & Acquisitions provide organisations with the opportunity to come together and avail mutual benefits and synergies that the partnership may potentially yield. However, as commonly known, M&As are like running a marathon when your left and right leg have never worked together. All it takes for things to go south is just a bruised knee.

According to Harvard Business Review, 70-90% of all mergers and acquisitions fail and are unable to retrieve meaningful benefits and just 14% of the respondents in PwC’s 2023 M&A Integration Survey indicated achieving significant success. Most mergers fail as the companies that come together are unable to integrate into a unit through proper communication and exchange. Therefore, let us dive further into the magical ingredient some partnerships had that helped them realise their synergies. To make a merger successful, the aspect of a carefully planned and executed ‘Post Merger Integration’ is of utmost importance. Post-Merger Integration comes into play both before and after the merger and it essentially is the process to ensure that the deal lives up to its predicted value. As broad of an aspect as it is, equally important are each of its individual components.

The planning aspect of a Post Merger Integration (PMI) starts well before the companies are merged. It prepares for the transition phase starting from Day 1 of the merger and that is when its strategies are put to action and the processes start, in order to extract values in the long term.

(source: Dealroom)

Integration is affected not only by the errors made post day 1, but also by errors made in earlier stages of the merger procedure along with the organisational operations, processes and cultural alignment. The last thing the companies want is to be left with a semi-merged organisation that isn’t able to deliver shareholder value and is worse off than the unmerged companies (which is the scenario is, in many cases). Every deal is unique and so should be the integration process. It must be meticulously designed ,taking into consideration the traits of both the companies. Using an ‘off-the-shelf’ plan may not yield the desired result in new-age companies or organisations that have drastically different processes.

Many companies do not invest meaningfully towards the integration process and this often leads to failed mergers where less value is extracted, or is often even lost. It was found that 78% of all successful M&As spent more than 6% of their deal size towards this process. Apart from financial investment, the key personnel and the leaders must also be personally invested towards unifying the individual units, as this has a significant long-term impact on the organisation’s performance and culture. Employees may not spare efforts towards cultural unification if they observe their leader to be indifferent. According to McKinsey’s research, 81% of M&As that met or surpassed their synergy expectations put key personnel in their integration process. In a merger or an acquisition, retention of talent and key personnel is crucial as these key aspects of an organisation drive it to success. 88% of successful M&As focused on retention of talent in their integration process.

The first step to a successful integration is to identify and analyse the source of value. It could be a particular function, innovation, culture or anything under the sun. To identify it, companies must carefully analyse each and every aspect of themselves and answer the question as to what makes them valuable. Such identification usually leads the pathway to determining the type of integration that the companies must undergo. It could be ‘absorption’, where one unit is completely absorbed by another and its operations and loses all of its own individual traits. It could be ‘holding’, which is typically used by conglomerates and large groups and the target enjoys a great level of decision-making authority but its culture ceases to exist. In cases of ‘symbiosis’, unlike a full integration (as in absorption), some value generating parts of the target which are better off unintegrated are left as it is. Finally, in cases of ‘preservation’, the integration is minimal and the acquired unit undergoes an insignificant change. 69% of all successful M&As carefully assess the type of integration.

Another important aspect is to set the synergy targets, which may be set or a defined period or from a defined function. These targets then act as a benchmark to analyse whether the integration process has been performing up to the mark. If not, early identification of value drainage points helps the companies steer the integration towards the right track. Integration is often said to be more effective when the companies are integrated by their roots. On ground integration is one of the key objectives of the whole process and companies aim to do that by understanding the daily operations, the personnel and key norms which may include wearing casuals on Fridays. Collectively, companies that target the operating model for on-ground integration are more likely to succeed in the unification process. In PwC’s M&A Integration Survey, it was found that 72% of all successful integrations targeted the operating model in their journey. However, focusing solely on the operating model may not guarantee success and therefore, other aspects, which may include technology integration or an effective communication strategy, must also be considered.

Integration may also be carried out on a function-by-function basis where each function of both units is analysed and integrated separately. Most of the successful M&As had the focus on Human Resources and Information Technology integration in common, above other aspects.

An anonymous senior level executive at Credit Suisse (UBS Group) with a vast experience in this space, particularly in the Indian onshore M&A segment, lists out the following crucial steps of a PMI process:-

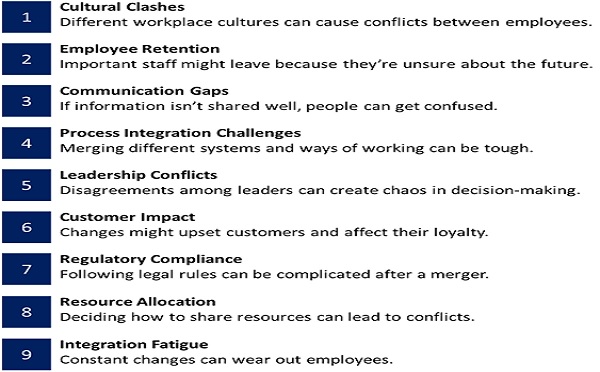

According to the same executive, the following are the key hurdles which hinder a PMI process: –

PMI Playbook: Navigating the Complex Integration Process

It all starts with planning pre day 1 where all the above listed aspects are analysed and a comprehensive plan is prepared to integrate the units to the required degree. Thereafter, integration becomes a part of the due-diligence and the process beyond. Navigating through company policies, organisational structure, business procedures and company culture, during the post-close review, synergies are reviewed and a new organisational form starts settling in in its own rhythm. The time it may take to finish the process may depend on deal by deal, but integration goes on indefinitely. The following checklist mentions end-to-end considerations that can be utilised to carry out the process right from the due-diligence:

The first step includes keeping in check synergy items and comparing them with expected integration costs.

Needless to say, integration costs must never exceed the synergy generation, If they do, the merger or acquisition is not viable for the company, and it will ultimately end up reducing its existing value. To identify such value creation and destruction points, both the participants’

functions, structure, and culture are checked, among other aspects. During an integration process, companies may resist employing their key personnel in the integration process as doing so may hinder their ongoing value creation through their core operating aspects. Such a cost of opportunity may carefully be considered while comparing costs and synergies.

Quite a number of pacts and agreements are to be signed between the parties and a lot of them are a part of the integration process.

These legal considerations form the basis of the integration process. The manner in which the units are integrated may be influenced by the nature, degree and specifications of the agreement betweeen the parties. After all of these considerations are catered to, the integration process keeps in mind the agreed terms while being enacted.

Information Technology, Finance and Human Resources are often considered to be the apex domains where integration is crucial. Unionising these aspects takes the most time and effort and these domains influence the success of the M&A to a large extent.

Information Technology ↔ Finance ↔ Human Resources

Starting with finance, a merger involves keeping in check whether the financial aspects of both companies reflect their true nature. This is done though a statutory audit. Accounting policies and norms are also compiled and matched and ultimately, which policies would continue is decided upon. Another important aspects that comes into play here is the determination of budget allocations and the integration of tax practices.

Moving on, we look at the cultural and human resource domain of the integration process. From the broad organisational policies to small rules and regulations, each and everything may be integrated.

In cases where there is a need of a high degree of innovation (typically in an acquisition of a new-age tech startup), an acquirer may decide to leave the recreational and cultural norms untouched. In other cases, they must be carefully vetted and a uniform policy must be implemented. The cultural integration may include: –

This also includes an analysis of communication norms such as the following.

The next domain that comes to picture is regarding Information and Communication Technology (ICT) and the following points must be catered to while integrating this particular domain of the two merged organisation.

The integration process doesn’t end here as there are numerous other parts and processes of the organisation that require tending to. An integration is not a process of just unifying activities but it also includes how information is being shared and how synergies are being extracted. Beyond that, it is also a process through which it is ensured that when such unified strategies are put to action, the organisations can stick together and function without falling apart.

In sales and marketing, the companies have to decide upon client information sharing related issues along with cross-selling policies among other aspects, which may look like this: –

This may also include how the companies decide to tend to after-sale services. In some cases, companies may acquire in order to get access to the clientele of the target company and that is where this domain is of utmost importance. Through exchange of sales and after-sale services, the companies can benefit from economies of scale and scope.

For management of the supply chain, there is little to cater to, on broader terms. But this may get complicated in practicality. Unification of the supply chain can lead to reduction in costs and improvement in efficiency in the operations of the organisations.

A similar case is the one of production, which may include: –

In many cases, companies may acquire another in order to leverage their technology in the acquirer’s ongoing operations, or to expand its operations. A hospital chain may acquire a drone technology company to help them in blood delivery. An API manufacturer may acquire a startup to help them in their ongoing medicine R&D. Such aspects are rampant in today’s world where startups are coming up with cutting-edge technologies. Hence, integration of technology is another crucial aspect which needs thorough analysis and evaluation. A technology integration checklist may include the following: –

This sums up most of the domains, aspects and processes which are to be performed and catered to, during the integration process.

Moving on, let us analyse the well-known Harvard Business School case study on Daimler Chrysler which highlights some of the key aspects which influence the success or failure of a merger or an acquisition. The case study revolves around two giant automobile manufacturers in distinct continents, coming together and fusing to extract synergies from their partnership and becoming a global leader through benefiting from each other’s expertise and operations.

From Promise to Pitfall: A Case Study on the Daimler-Chrysler Unionisation

The merger of Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft with Benz & Cie. Rheinische Gasmotorenfabrik resulted in the formation of Daimler-Benz in 1926. This German company evolved quite rapidly, with their premium cars being famous for their comfort and class, and emerged as a luxurious car brand well-known across Germany and Europe.

Despite their success in Europe, their cars were unable to capture anywhere more than 1% market share in the giant American markets, where the presence of Ford and General Motors was so strong, that it was impractical to hinder their market share. The difference in preferences between the European and American consumers acted as another barrier to entry in the U.S.A.

However, aspirations never came to a halt and still prevailed in 1998, when the company decided to merge with an American counterpart – Chrysler Corporation ( a wholly owned subsidiary of Fiat SpA, at present). During those years, Daimler Benz has been enduring financial troubles on multiple ends. Sales had been declining and so was the profitability and the company just wasn’t big enough to survive the global competition. Moreover, the high-quality standards of the company posed obstacles to capture the consumer automobile segment of America.

On the American side, Chrysler was known for their affordable cars for the masses. The company’s manufacturing process were the epitome of high efficiency production with low costs of product design and development. They had quite a chunk (23%) of the American market space but to compete with its global counterparts, it just wasn’t enough. Having faced bankruptcy four times since the end of World War II, the company faced similar situations again— sales and profitability declining and payments overdue.

During the latter half of the 1990s, these declines were a market trend. Automobile industry across the world faced similar problems and the times were only getting harder. The rising bargaining power of the customers, the increasing environmental regulations and the challenges of overcapacity were predominant. Finally, to survive through the hardship with the aim to be the third largest automobile company in the world after General Motors and Ford by benefitting from each other’s area of expertise, Daimler-Benz decided to merge with Chrysler Corporation in 1998. For Daimler-Benz, this merger seemed to be highly beneficial as the yearly revenues, profitability, efficiency and low-cost production along with a rigid distribution network of Chrysler in the U.S could have helped it achieve critical mass, for which it was just not big enough. Chrysler’s expertise in low-cost production would have been the perfect match for Daimler’s operations. On the other side, Chrysler wanted an escape from its current despair and with the help of Daimler, it could not only do that, but achieve its long-awaited dream of capturing the U.S. markets.

At hindsight, the parties seemed the perfect counterpart for each other. The synergies which were expected to be extracted were lucrative to both companies and the best part – none of them wanted to hinder each other’s operations by putting their own needs above the other, and they simply wanted a firm handshake for mutual benefits and a unified front. That is, a ‘merger of equals.’ At hindsight, there weren’t any significant differences between how things ran in both companies. They both seemed to focus on similar things to achieve the same goal – to capture the world’s car industry.

However, what the management of both the companies failed to take into account is the cultural differences that prevail. The companies were operating in different economic and cultural territories which had significant differences from each other in terms of culture. In a merger of equals, it is particularly difficult to integrate the cultures of two separate and significantly distinct companies into one shared common culture. In general, the integration of organisational culture is through three main stages – shock, stress and willingness to accept.

Shock ↔ Stress ↔ Willingness to Accept

It is very unlikely that the use of pieces of separate puzzles combined to solve a single one may yield something meaningful. Unlike the case of acquisition, where the acquirer’s culture is imposed on the target, a merger of equals poses a massive hinderance in the post-merger integration process due to its complexity and attempt to find a common ground, which may not always be feasible. Contrary to the general rule of thumb, the output of the integration of organisational cultures in a merger of equals may not reduce the effect of the stock stage but it may lead to higher stress and a lack of willingness to accept. In the shock and the stress stage, right from the announcement of the merger, internal rivalry starts brewing between the employees which impedes the integration process. Along with that, it causes qualified and trained employees to undergo unwanted stress and pressure, which they may very easily avoid by leaving the organisation. It further leads to a lack of availability of qualified personnel which could be employed in the integration process.

This was evident in the case of the merger between Daimler Benz and Chrysler Corp. where even a supposedly ‘peaceful’ merger led to a significant loss of talent. This was primarily on the Chrysler side and the reason for it, we shall discuss further in this study. For now, let us talk about how exactly did the two entities differ in their corporate and organisational culture. The majority of the differences between the cultures of the two organisations came into light in the daily activities and routines. Chrysler Corporation had the features of a typical American company – an environment where the employees were encouraged to break norms to ideate and solve problems. The degree of freedom in looking for new solutions was quite high as the organisation valued creativity. On the other hand, the Germans were a stickler to rules. Predetermined methodologies, compliance with the norms and less scope for creativity; but it would always get the job done. Where Daimler focused on a more-or-less authoritative structure of organisation with a centralised decision making, employee empowerment was in the core values of Chrysler. And with employee empowerment came higher pays – leading to a steep difference between the employee pay levels of both the counterparts who had come together to make it work. And they tried to make it work too. Several workshops, employee training programmes and team bonding events, but it just did not seem to help the ship sail. After all, it is tough to make right with it when an American employee who gets transferred to the German office earns twice as much as his German supervisor.

Following pre-set methodologies which included intensive red-tapism, long approval procedures and prescribed execution plans and on the other hand simply using trial and error to see what fits, featured the German and the American sides of the business respectively. And even with all their efforts, the management could not come up with a culture that reflected a perfect blend of both the organisations – ultimately leading to the failure of this merger of equals.

With all this, the companies went through severe talent loss. Key personnel from both the organisations had left which hindered the organisational functions, and therefore hindering what the two organisations wanted to gain from this merger – efficiency of Chrysler and the Class of Daimler-Benz. With all these events happening and having realised that the merger may, after all, not work, the ‘equal’ status of the two companies started fading away. The executives of the two companies did not seem to come to an agreement as to where to lead the joint boat and it appeared to be the problem that Daimler-Benz had neither acquired Chrysler, nor was it given an equal status.

Initially, the German party allowed Chrysler to do things the way it has been doing for long – betting on its track record. But now that the situation had changed with employees leaving the organisation and with the realisation that the merger may not work at all, Daimler started imposing its own ways and its management took over the whole company. This series of events further worsened the situation, ultimately leading to the failure of the merger where both companies were left in a worse state than before and now unable to survive through the worldwide hardships prevailing in the industry. In the third quarter of the year 2000, Chrysler incurred a massive loss of $512 million causing the share price to drop to $40 from $108 in January 1999. This ultimately led to the sale of the Chrysler division in 2007.

~With mentorship from a Credit Suisse (UBS Group) Senior Level Executive | India Onshore M&A Integration~

Source: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/how-the-best-acquirers-excel-at-integration#/