Exposure Draft

Guidance Note on Accounting by E-commerce and Cloud Computing Companies

(Last date of comments: May 31, 2020)

Research Committee

The Institute of Chartered Accountants of India

(Set up by an Act of Parliament)

New Delhi

Exposure Draft

Guidance Note on Accounting by E-commerce and Cloud Computing Companies

Research Committee of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of India invites comments on any aspect of this Exposure Draft of the ‘Guidance Note on Accounting by E-commerce and Cloud Computing Companies’. Comments are most helpful if they indicate the specific paragraph or group of paragraphs to which they relate, contain a clear rationale and, where applicable, provide a suggestion for alternative wording.

Comments should be submitted in writing to the Secretary, Research Committee, The Institute of Chartered Accountants of India, ICAI Bhawan, Post Box No. 7100, Indraprastha Marg, New Delhi – 110 002, to be received not later than May 31, 2020. Comments can also be sent by e-mail at research@icai.in .

(The following is the text of the Guidance Note on Accounting by E-commerce and Cloud computing companies, issued by the Institute of Chartered Accountants of India. With the issuance of this Guidance Note, the Guidance Note on Accounting by Dot- Com Companies, issued by the Institute of Chartered Accountants of India in February 2001, stands withdrawn.)

Introduction

1. This Guidance Note deals with accounting by e-commerce and cloud-computing companies in respect of certain issues relating to revenue and expense recognition.

2. Some of the accounting issues in e-commerce and cloud-computing companies have arisen due to the new business models being used in such Some accounting issues, such as those relating to advertising partnerships, rebates, point and loyalty programmes, which are more common in business carried on by e-commerce and cloud-computing companies, also exist in other businesses.

E commerce companies

3. E-commerce (electronic commerce) is the activity of electronically buying or selling of products on online services or over the Internet. Electronic commerce draws on technologies such as mobile commerce, electronic funds transfer, supply chain management, internet marketing, online transaction processing, electronic data interchange (EDI), inventory management systems, and automated data collection systems. E-commerce is in turn driven by the technological advances of the semiconductor industry and is the largest sector of the electronics industry. E-commerce is a business model that lets the firms and individuals conduct business over electronic networks, such as internet.

4. E-commerce, which can be conducted over computers, tablets, or smartphones may be thought of like a digital version of mail-order catalogue Nearly every imaginable product and service is available through e-commerce transactions, including books, music, plane tickets, and financial services such as stock investing and online banking. As such, it is considered a very disruptive technology.

5. One form of e-commerce companies is that of on-line content companies focus on the content sites, i.e., the internet sites that provide news, information and knowledge as their main business. These include companies that provide Internet navigation services and reference guide information for World Wide Web and that publish, provide or present proprietary, advertising, and/or third-party content. Examples of content sites include askjeeves.com, infoseek.co.za, indiainfonline.com, yahoo.com, etc.

6. Another form of e-commerce is electronic retailing (e-tailing) is the sale of goods and services through the E-tailing can include business-to-business (B2B) and business-to-consumer (B2C) sales of products and services. E-tailing requires companies to tailor their business models to capture Internet sales, which can include building out distribution channels such as warehouses, Internet webpages, and product shipping centers. Examples of e-tailing vendors are Flipkart, Amazon, Makemytrip, Yatra.com, Trivago and Grofers. Electronic retailing includes a broad range of companies and industries.7. Internet commerce companies sell products and services over the websites on the Internet and include on-line dealers.

7. E-commerce operates in all four of the following major market segments:

- Business to business (B2B)

- Business to consumer(B2C)

- Consumer to consumer(C2C)

- Consumer to business(C2B)

8. B2B sites link different businesses or different parts of a business. Transactions on these sites take place between industrial manufacturers, wholesalers or retailers. Special features of these transactions are high volumes per customer, lesser number of customers, secured payment systems, privacy of information, etc. Examples of sites in this category are indiaconstruction.com, clickforsteel.com and seekandsource.com.

9. B2C sites sell products or services directly to A large number of e-commerce companies fall in this category. Transactions on these websites are characterised by low volumes per consumer and a large number of consumers. Examples of sites in this category are flipkart.com, amazon.com, rediff.com, jaldi.com, indiatimes.com, zipahead.com, and fabmart.com.

10. C2C sites enable consumers to buy and sell from each other through auction or other similar sites. Examples of sites in this category are bazee.com, snapdeal.com, olx.com, quikr.com, jabong.com, ebay.com, myntra.com and com.

11. C2B sites enable consumers to set prices and business enterprises bid to offer products and services. Examples of sites in this category are razorfinish.com and priceline.com.

12. There are many ways companies can earn revenue online. Of course, the first income source is through the sales of their product to consumers or However, both B2C and B2B companies could earn revenue by selling their services through a subscription-based model such as Netflix, Amazon Prime, which charges a monthly fee for access to media content. Revenue can also be earned through online advertising. For example, Facebook earns revenue from ads placed on its website by companies looking to sell to Facebook users.

Elements of e-commerce transaction

13. In an e-commerce transaction, all the traditional elements of commerce exist though with some differences. The following elements are ordinarily present in an e-commerce transaction:

- A product or service;

- a place, namely, a website, that displays the products/services and where a business transaction takes place;

- a way for the people to visit the place (website);

- a way to accept orders, e.g., an on-line form;

- a way to accept consideration for the transaction – normally through credit

14. Alternatively, the companies may use more traditional billing techniques either on-line or through the mail;

- a facility to ship products to customers (often, outsourced). In the case of software and information, the product can be transferred over the Web through a file download mechanism;

- a way to accept rejected/returned goods and services;

- a way to handle warranty claims, if necessary; and

- a way to provide customer service [often through e-mail, on-line forms, on-line knowledge bases and frequently asked questions (FAQs)].

15. Apart from the above elements of e-commerce transactions, certain facilities are also provided on the website, for example, information of the exact status of an order may be provided to the customer.

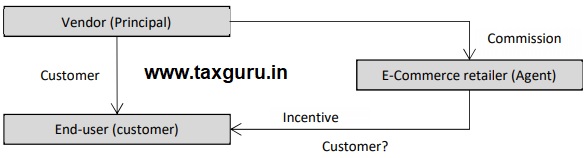

Cloud Service companies

16. Cloud computing is the delivery of computing services—servers, storage, databases, networking, software, analytics, intelligence and more—over the Internet (“the cloud”) to offer faster innovation, flexible resources and economies of Users typically pay only for cloud services they use, helping lower their operating costs, run your infrastructure more efficiently and scale as their business needs change. Cloud computing services often involve on-demand availability of computer system resources, especially data storage and computing power, without direct active management by the user. The term is generally used to describe data centers available to many users over the Internet. Large clouds, predominant today, often have functions distributed over multiple locations from central servers. If the connection to the user is relatively close, it may be designated an edge server.

The following is an illustrative diagram of cloud computing:

Source: Wikipedia

17. Cloud services arrangements may include the cloud services (such as software-as-a-service (SaaS)) or other products or These arrangements also frequently include a licence of the software, for which the customer may (or may not) have the right to take possession. Cloud services entities also frequently offer professional services, such as implementation, data migration, business process mapping, training and project management services, in addition to the cloud service itself. These professional services may be required for a customer to begin using the cloud services in the manner described in the contract.

18. Cloud computing eliminates the capital expense of buying hardware and software and setting up and running on-site datacentres—the racks of servers, the round-the-clock electricity for power and cooling, the IT experts for managing the infrastructure.

19. On-site datacentres may require a lot of operational efforts such as hardware set up, software patching and other time-consuming IT management issues. Cloud computing removes the need for many of these tasks, so IT teams can spend time on achieving more important business goals.

20. The benefits of cloud computing services include the ability to scale In cloud speak, that means delivering the right amount of IT resources—for example, more or less computing power, storage, bandwidth—right when it is needed and from the right geographic location.

Scope

21. E-commerce and cloud service companies engaged in transactions that are similar to transactions entered into by other businesses should follow generally accepted accounting principles for recording those transactions. Similarly, in case of companies normally carrying on other businesses, the recommendations contained in this Guidance Note should be applied for recording e-commerce and cloud service transactions undertaken by them.

This Guidance Note applies to companies preparing their financial statements under Companies (Accounting Standards) Rules, 2006 under Section 133 of Companies Act, 2013 as well as those companies applying preparing their financial statements under Companies (Indian Accounting Standards) Rules, 2015 under section 133.

Revenue Recognition

22. The main sources of revenue of e-commerce companies presently include:

- Membership and subscription;

- Merchandising activities;

- Advertising services; and

- Other services like web-hosting, content selling,

E-commerce companies are often valued based on revenue multiples and, therefore, it is one of the most important performance parameters. Most e-commerce companies either accept payments online through credit cards, internet banking, debit cards or cash on delivery. Further, in most cases, the delivery is the responsibility of the company and, hence, it is important to determine when does the ‘risk and rewards’ under Companies (Accounting Standards) Rules, 2006 or when does the ‘control’ under Companies (Indian Accounting Standards) Rules, 2015 get transferred to the customer. This is an important issue for business-to-customer as well as business-to-business models.

23. In respect of entities which are not subject to Indian Accounting Standards (Ind AS) Framework, the basic principles of revenue recognition as set out in Accounting Standard (AS) 9, ‘Revenue Recognition’, notified under Companies (Accounting Standards) Rules, 2006 and that issued by the ICAI apply to recognition of revenue from the above sources. The relevant extracts from AS 9 that are relevant in this context are reproduced below:

“4.1 Revenue is the gross inflow of cash, receivables or other consideration arising in the course of the ordinary activities of an enterprise from the sale of goods, from the rendering of services, and from the use by others of enterprise resources yielding interest, royalties and dividends. Revenue is measured by the charges made to customers or clients for goods supplied and services rendered to them and by the charges and rewards arising from the use of resources by them. In an agency relationship, the revenue is the amount of commission and not the gross inflow of cash, receivables or other consideration.”

“10. Revenue from sales or service transactions should be recognised when the requirements as to performance set out in paragraphs 11 and 12 are satisfied, provided that at the time of performance it is not unreasonable to expect ultimate collection. If at the time of raising of any claim it is unreasonable to expect ultimate collection, revenue recognition should be postponed.”

“11. In a transaction involving the sale of goods, performance should be regarded as being achieved when the following conditions have been fulfilled:

(i) the seller of goods has transferred to the buyer the property in the goods for a price or all significant risks and rewards of ownership have been transferred

to the buyer and the seller retains no effective control of the goods transferred to a degree usually associated with ownership; and

(ii) no significant uncertainty exists regarding the amount of the consideration that will be derived from the sale of the ”

“12. In a transaction involving the rendering of services, performance should be measured either under the completed service contract method or under the proportionate completion method, whichever relates the revenue to the work accomplished.

Such performance should be regarded as being achieved when no significant uncertainty exists regarding the amount of the consideration that will be derived from rendering the service.”

24. In respect of entities which are subject to Indian Accounting Standards (Ind AS) Framework i.e. Companies (Indian Accounting Standards) Rules, 2015, revenue recognition and measurement are based on the requirements of Ind AS 115 Revenue from Contracts with Customers. Ind AS 115 specifies the requirements an entity must apply to recognise and measure revenue and the related cash flows. The core principle of the standard is that an entity will recognise revenue at an amount that reflects the consideration to which the entity expects to be entitled in exchange for transferring promised goods or services to a customer. The relevant extracts from Ind AS 115 that are relevant in this context are reproduced below:

Identifying the contract

9 An entity shall account for a contract with a customer that is within the scope of this Standard only when all of the following criteria are met:

(a) the parties to the contract have approved the contract (in writing, orally or in accordance with other customary business practices) and are committed to perform their respective obligations;

(b) the entity can identify each party’s rights regarding the goods or services to be transferred;

(c) the entity can identify the payment terms for the goods or services to be transferred;

(d) the contract has commercial substance (ie the risk, timing or amount of the entity’s future cash flows is expected to change as a result of the contract); and

(e) it is probable that the entity will collect the consideration to which it will be entitled in exchange for the goods or services that will be transferred to the In evaluating whether collectability of an amount of consideration is probable, an entity shall consider only the customer’s ability and intention to pay that amount of consideration when it is due. The amount of consideration to which the entity will be entitled may be less than the price stated in the contract if the consideration is variable because the entity may offer the customer a price concession (see paragraph 52).

Identifying performance obligations

22 At contract inception, an entity shall assess the goods or services promised in a contract with a customer and shall identify as a performance obligation each promise to transfer to the customer either:

(a) a good or service (or a bundle of goods or services) that is distinct; or

(b) a series of distinct goods or services that are substantially the same and that have the same pattern of transfer to the customer (see paragraph 23).

46 When (or as) a performance obligation is satisfied, an entity shall recognise as revenue the amount of the transaction price (which excludes estimates of variable consideration that are constrained in accordance with paragraphs 56–58) that is allocated to that performance obligation.

Determining the transaction price

47 An entity shall consider the terms of the contract and its customary business practices to determine the transaction price. The transaction price is the amount of consideration to which an entity expects to be entitled in exchange for transferring promised goods or services to a customer, excluding amounts collected on behalf of third parties (for example, some sales taxes). The consideration promised in a contract with a customer may include fixed amounts, variable amounts, or

Allocating the transaction price to performance obligations

73 The objective when allocating the transaction price is for an entity to allocate the transaction price to each performance obligation (or distinct good or service) in an amount that depicts the amount of consideration to which the entity expects to be entitled in exchange for transferring the promised goods or services to the customer.

25. On the basis of the above, accounting principles applicable to specific sources of revenue of e- commerce companies are discussed in the following Under both AS 9 and Ind AS 115, one of the indicators to determine the timing of revenue recognition is to know who bears the insurance costs and risk. In practice, many large e-retail enter into agreements with logistics providers who bear insurance cost and risk of delivery. Under such contracts, companies would recognise revenue on despatch of goods from the warehouse. However, when the cost of delivery is built into the pricing of the product and the cost of transport is borne by the e-commerce entity, then the risk of delivery and loss is still with the e-commerce company. In such cases, it may be appropriate to recognise revenues only once the products are delivered to the customer.

Further, in practice, the customers are often provided with an option to return the goods sold. It is important to evaluate each such offer more specifically to understand the facts and circumstances and their implications on accounting. Generally, when the buyer has a right of return and there is uncertainty about the possibility of return, revenue is not recognised until the shipment has been accepted by the customer/ goods are delivered to the customer and the time period for rejection has elapsed.

Historical experience may be considered in assessing the possibility of return. If based on past experience, the entity can make a reliable estimate of the amount of the goods that may be returned, then it would be appropriate to recognise revenue for the amount that is expected to be received for items that are not returned if other conditions for revenue recognition are met.

Upfront fee for membership and subscription

26. Many a times, entities receive upfront payments from customers before they provide the contracted service or deliver a good. Such upfront fees generally relate to the activation or set-up of a good to be used or a service to be provided in the In many cases, the upfront amounts paid by the customer are non-refundable. In order to avail of the services provided by e-commerce entities, consumers are usually required to pay an amount as membership fees or subscription. Such membership fee or subscription may also be collected in the form of registration fee. While some services are available to members free of cost after registration, other services may be made available only on payment of an additional fee.

27. The membership/registration fees received by a e-commerce company may fall in the following categories:

- Non-refundable fees that entitle a member to use the services of the website by making payment for all services separately;

- Non-refundable fees that entitle a member to use the services of the website indefinitely without making any further payment for use of services;

- Non-refundable fees that entitle a member to use the services of the website for a specified period of time;

- Fees that are refundable subject to the fulfilment of certain conditions stipulated in the subscription agreement. Usually contractual stipulations require such conditions to be fulfilled within a specified time period; and

- Periodic membership/subscription fees on monthly, quarterly, annual or such other

28. E-commerce companies often offer membership services to customers, wherein customers pay non- refundable upfront fees to the e-commerce company. In return, the members (customers) get, for example, discounts and other benefits in partner

29. Under Companies (Accounting Standards) Rules, 2006, AS 9 contains guidance on the recognition of non-refundable fees as revenue

30. Revenue earning process is completed by performance of specified actions as per the terms of the arrangements, not simply by originating a revenue generating

31. Supply of products or rendering of services by e-commerce companies may involve charge of a non-refundable upfront fee/initial (membership/ registration) fee with or without subsequent payments for products or services to be provided in future. In those cases where all products or services are to be separately paid for apart from the initial membership fee, the initial membership fee is of the nature of an entrance fee which should be capitalised and revenue from rendering of services or supply of products should be recognised on the basis specified in this regard in AS

32. With regard to non-refundable fees that entitle a member to use the services of the website indefinitely without making any further payment for use of services, the initial fee, in substance, represents wholly or partly an advance payment for products or services to be provided in future. This implies that it is expected that the services would be provided on a continuous basis after payment of up-front fee. The non-refundable up-front fee and the continuing performance obligation related to the services to be provided or products to be delivered form an integrated

33. Accordingly, up-front membership fees, even if non-refundable, are actually earned as the products and/or services are delivered and/or rendered over the term of the arrangement or the expected period of performance.

34. Consequently, recognition of such non-refundable fees should be generally deferred and the same should be recognised systematically over the period(s) during which fees are However, keeping in view the uncertain nature of business of an e-commerce company, non-refundable fees that entitle a member to use the services of the website indefinitely should be recognised as revenue over a reasonable period on a systematic and rational basis, i.e., on time proportion basis or any other basis, e.g., usage basis, whichever is more representative of the services rendered. In case the company also provides services for periodic subscription, the revenue in respect of non-refundable fees to be recognised on the aforesaid basis should not exceed the corresponding periodic subscription.

35. Non-refundable fees that entitle a member to use the services of the website for a specified period of time in excess of the reasonable period of time determined as per paragraph 34 above should be recognised as revenue over a longer period of time based on the members’ entitlements.. However, in case the specified period is less than the reasonable period determined as per paragraph 34, the fees should be recognised as revenue on a systematic and rational basis usually on a time proportion basis over the specified period unless another systematic and rational basis is more representative of the services rendered, e.g., the usage

36. In respect of membership fees that are refundable to members subject to fulfilment of certain conditions (for example, a stipulated volume of usage within a specified period, etc.), it is not appropriate to recognise such fees as revenue on receipt thereof since it is expected that a member would ordinarily fulfil the conditions. Accordingly, the revenue from such transactions should be recognised when it becomes reasonably certain that conditions would not be fulfilled. Pending the recognition of revenue as aforesaid, the amounts received from customers should be credited and retained in a liability account such as ‘Customers Refundable Fees Account’. The company should periodically review the status of this account to ascertain the extent of fulfilment or otherwise of the conditions.

37. Periodic membership subscriptions paid by members to avail of the services offered by the website should be recognised as revenue over the period of the subscription, in accordance with the principles of AS

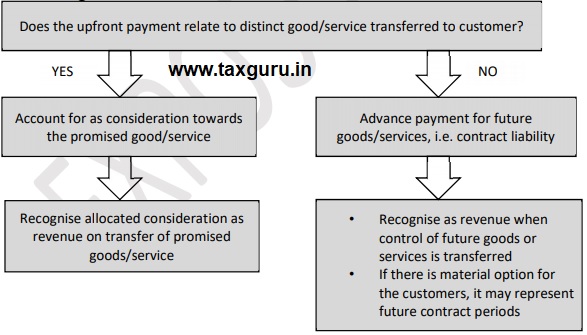

38. Under Companies (Indian Accounting Standards) Rules, 2015, under Ind AS 115, there is specific guidance for accounting for upfront non-refundable fee revenue:

“B48 In some contracts, an entity charges a customer a non-refundable upfront fee at or near contract inception. Examples include joining fees in health club membership contracts, activation fees in telecommunication contracts, setup fees in some services contracts and initial fees in some supply contracts.

B49 To identify performance obligations in such contracts, an entity shall assess whether the fee relates to the transfer of a promised good or service. In many cases, even though a non-refundable upfront fee relates to an activity that the entity is required to undertake at or near contract inception to fulfil the contract that activity does not result in the transfer of a promised good or service to the customer (see paragraph 25). Instead, the upfront fee is an advance payment for future goods or services and, therefore, would be recognised as revenue when those future goods or services are provided. The revenue recognition period would extend beyond the initial contractual period if the entity grants the customer the option to renew the contract and that option provides the customer with a material right as described in paragraph B40.

B50 If the non-refundable upfront fee relates to a good or service, the entity shall evaluate whether to account for the good or service as a separate performance obligation in accordance with paragraphs 22–30.

B51 An entity may charge a non-refundable fee in part as compensation for costs incurred in setting up a contract (or other administrative tasks as described in paragraph 25). If those setup activities do not satisfy a performance obligation, the entity shall disregard those activities (and related costs) when measuring progress in accordance with paragraph B19. That is because the costs of setup activities do not depict the transfer of services to the customer. The entity shall assess whether costs incurred in setting up a contract have resulted in an asset that shall be recognised in accordance with paragraph 95.”

39. Entities must evaluate whether a non-refundable upfront fee relates to the transfer of a good or service. If it does, the entity is required to determine whether to account for the promised good or service as a separate performance obligation. Fees received towards setting-up of activities do not depict the transfer of services to a These should also be ignored when measuring progress of an entity’s performance.

40. Even though a non-refundable upfront fee relates to an activity that the entity is required to initially undertake towards the contract, in many cases, that activity will not result in the transfer of a promised good or service to the customer.

41. Non-refundable up-front fee may indicate that the arrangement includes an option to the customer for additional goods or services (e.g., renewal option for future goods or services at a reduced price, if the customer renews the agreement without the payment of an additional upfront fee). In such a case, an entity needs to assess to determine whether the option is a material right (i.e., another performance obligation in the contract). If the entity concludes that the non-refundable upfront fee does not provide a material right, the fee would be part of the consideration allocable to the goods or services in the contract and would be recognised when (or as) the good or service to which the consideration was allocated is transferred to the customer.

42. Non-refundable upfront fee that provides a material right to the customers, the amount of the fee allocated to the material right would be recognised over the period of benefit of the fee, which may or may not be the estimated customer

The following diagram depicts the allocation of a non-refundable upfront fee determined to be a material right:

Example: Non-refundable upfront fees – restaurant membership fees

A customer signs a one-year contract with a Pomato Gold, an e-commerce entity, and is required to pay both a non-refundable initiation fee of Rs.10,000 and an annual membership fee in monthly instalments of Rs.4,000. The members get discounts and other benefits in

partner restaurants across India. At the end of each year, the customer can renew the contract for an additional year without paying an additional initiation fee. The customer is then required to pay an annual membership fee in monthly instalments for each renewal period. Pomato’s activity of registering the customer does not transfer any service to the customer and, therefore, is not a performance obligation. By not requiring the customer to pay the upfront membership fee again upon renewal, Pomato is effectively providing a discounted renewal rate to the customer.

Pomato determines that the renewal option is a material right because it provides a renewal option at a lower price than the range of prices typically charged for new customers. Therefore, it is a separate performance obligation. Based on its experience, Pomato determines that its customers, on average, renew their annual memberships twice before terminating their relationship with Pomato. As a result, Pomato determines that the option provides the customer with the right to two annual renewals at a discounted price. In this scenario, Pomato would allocate the total transaction consideration of Rs.58,000 (Rs.10,000 upfront membership fee + Rs.48,000 (Rs.4,000 x 12 months)) to the identified performance obligations (monthly services for the one-year contract and renewal option) based on the relative stand-alone selling price method. The amount allocated to the renewal option would be recognised as each of the two renewal periods is either exercised or forfeited.

Alternatively, Pomato could value the option by ‘looking through’ to the optional goods and services using the practical alternative provided in Ind AS 115.B42. In that case, it would determine that the total hypothetical transaction price (for purposes of allocating the transaction price to the option) is the sum of the upfront fee plus three years of service fees Rs.154,000(i.e.,Rs.10,000 + Rs.144,000) and would allocate that amount to all of the services expected to be delivered or 36 months of membership (or Rs.5,144 per month). The amount allocated to the renewal option would be recognised as revenue over each renewal period. One acceptable approach would be to reduce the initial Rs.10,000 deferred revenue balance for the material right by Rs.278 each month (Rs.10,000 / 36 months remaining), assuming that the estimated renewal period of two years remains unchanged.

Example: Recognition of Upfront fee by cloud service company

A Ltd, a cloud service company, enters into a contract with a customer for a licence of its software and a non-cancellable one-year subscription to access the licensed application (the cloud services). The contract amount for the software licence is an upfront, non-refundable fee of Rs.10 Lakhs. The fee for the cloud services is Rs. 500,000 for one year. Therefore, the total fees paid by the customer for the first year’s subscription is Rs. 15,00,000. The customer has the right to renew the cloud services each year for Rs.500,000.

Assume that A Ltd. determines the software licence and cloud services are a single performance obligation. There are no other promised goods and services in the contract. Therefore, the upfront fee is not associated with the transfer of any other good or service to the customer. However, A Ltd. determines there is an implied performance obligation. That is, the right to renew the cloud services each year for Rs.500,000 is a material right to the customer because that renewal rate is significantly below the rate the customer paid for the first year of service (Rs.15 Lakhs in total).

Based on its experience, A determines that its average customer relationship is three years. As a result, A determines that the performance obligations in the contract include the right to a discounted annual contract renewal and that the customer is likely to exercise twice. Therefore, A defers the non-refundable upfront fee of Rs.10,00,000 and recognises the same over the three years on a straight-line basis.

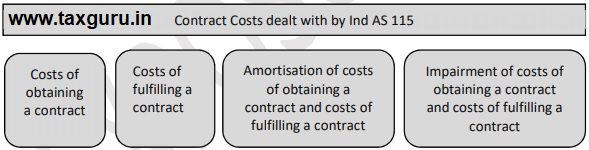

Merchandising activities

43. In case of e-commerce entities, generally multiple parties are involved in providing good and services. When there are multiple parties involved in providing goods or services to a customer, an entity evaluates the nature of its promise to the customer. If an entity assumes the risks and rewards and obtains control of another party’s goods or services before transferring the risks and rewards and control to the customer, then the entity’s promise is to provide the goods or services itself. Therefore, the entity is acting as a principal for accounting purpose. In such cases, the entity records revenue on a gross

44. On the other hand, if the entity does not control the goods or services before it is transferred to the customer, then the entity is acting as an agent for accounting purpose and arranges for that good or service to be provided by another In such cases, the entity records as revenue the net amount that it retains for its agency services.

45. One of the significant issues in accounting by e-commerce companies is whether to recognise gross amount of revenues and the related cost of sales or to recognise the revenue on net basis, similar to commission. The significance of this issue is enhanced due to the importance often placed on the revenue being used as the basis for valuation of e-commerce

46. The question of gross versus net revenue and cost recognition ordinarily arises in connection with e-commerce companies that distribute or resell third party products or services. This issue typically arises in the B2C sites. Due to the legal framework in India, a B2B entity may not be allowed to make a sale to retail customers and is required to sell its goods to a B2C This relationship can also have an impact on the presentation of revenue is the books of the B2B and B2C companies on a gross or net basis.

47. In assessing whether revenue should be reported on gross basis with separate recognition of cost of sales or on net basis, under AS 9, it should be considered whether the e-commerce company:

- acts as a principal in the transaction, e., it assumes significant risks and rewards of ownership, such as the risk of loss in collection, delivery, or returns; or

- acts as an agent or broker for sale of goods or rendering of services, i.e., does not assume significant risks and rewards of ownership; compensation being commission or In this case, the e-commerce company is merely engaged in providing the service of bringing the purchaser and the seller together.

48. Where a e-commerce company acts as a principal in the transaction, i.e., significant risks and rewards of ownership are first acquired by it and then transferred on sale, it is appropriate to recognise revenues and the related costs on a gross basis. If the e-commerce company does not do so, i.e., it merely acts as an agent, it would be appropriate to recognise only the service charges as revenue, similar to

49. The Technical Guide on Accounting Issues in the Retail Sector is issued by the Institute of Chartered Accountants of India, provides guidance on presentation of As per the Technical Guide, some of the factors that indicate that an entity is acting as a principal in transactions could include (indicative list only):

- The customer understands that the entity is acting as the primary obligor in the arrangement

- The entity is able to set the selling price with the customer

- The entity has inventory risk

- The entity performs part of the services provided or modifies the goods supplied

- The entity has or assumes the credit risk associated with the transaction

50. Determining whether an entity is acting as an agent or principal is based on an evaluation of the risks and responsibilities taken by the entity, including factors as mentioned above such an inventory risk and responsibility for the delivery of goods or

51. Revenue represents the amount received by an entity for its own Therefore, for a principal, revenue should be presented at its gross amount and is measured before deducting related costs such as cost of materials and salaries. On the other hand, in an agency relationship, the amounts collected on behalf of and passed on to the principal is not revenue of the agent. The revenue of the agent is the amount of net margin, plus any other amount charged by the agent to the principal or other parties. The revenue collected from the ultimate customer (net of taxes) is recorded as revenue by the principal. The principal recognises the consideration retained by the agent as a cost.

52. Common example is that of an e-commerce company purchasing traded goods from a wholesaler. E-commerce company generally would sell these goods to the end customer and may or may not carry the associated inventory risk as it purchases goods from the wholesaler only when it receives orders from the end customer. However, it may bear the risk of those inventory items that have been returned by the customer. In such cases, the e-commerce company does not seem to bear significant inventory risk, however, it may bear the following:

- Credit risk

- Is primary responsible for providing the goods to the customer, i.e., fulfilling the order

- Direct pricing discretion

- Discretion is selecting the supplies/ wholesaler

In such a case, the e-commerce company may asses the above criteria to be significant and reflect the gross billing to its customers as its revenue.

53. Under Companies (Indian Accounting Standards) Rules, 2015, Ind AS 115 contains the overall principle for the principal versus agent evaluation. These are little different from the indicators contained in Technical Guide on Accounting Issues in the Retail Sector. The relevant extracts of Ind AS 115 in the context are as follows:

B34 When another party is involved in providing goods or services to a customer, the entity shall determine whether the nature of its promise is a performance obligation to provide the specified goods or services itself (i.e., the entity is a principal) or to arrange for those goods or services to be provided by the other party (i.e., the entity is an agent).

B34A To determine the nature of its promise (as described in paragraph B34), the entity shall:

(a) Identify the specified goods or services to be provided to the customer (which, for example, could be a right to a good or service to be provided by another party (see paragraph 26)); and

(b) Assess whether it controls (as described in paragraph 33) each specified good or service before that good or service is transferred to the

B35 An entity is a principal if it controls the specified good or service before that good or service is transferred to a customer. However, an entity does not necessarily control a specified good if the entity obtains legal title to that good only momentarily before legal title is transferred to a customer. An entity that is a principal may satisfy its performance obligation to provide the specified good or service itself or it may engage another party (for example, a subcontractor) to satisfy some or all of the performance obligation on its behalf.

54. An entity determines whether it is a principal or an agent for each specified good or service promised to the customer. A specified good or service is a distinct good or service (or a distinct bundle of goods or services) to be provided to the customer. If a contract with a customer includes more than one specified good or service, an entity could be a principal for some specified goods or services and an agent for

55. Following examples illustrate the accounting treatment.

Example: Restaurant/hotel coupon services

A Ltd. is an entity that sells restaurant/hotel electronic coupons on its mobile application and website. The vouchers sold by A Ltd. entitle customers to future meals at specified restaurants and hotels. The sales price of the voucher provides the customer with a significant discount ranging from 20% to 80% when compared with the normal selling prices of the meals and hotel room tariff. For example, a customer pays Rs. 1,000 for a voucher that entitles the customer to a meal at a restaurant that would otherwise cost Rs. 2,000. A Ltd. does not purchase or commit itself to purchase vouchers in advance of the sale of a voucher to a customer; instead, it purchases vouchers only as they are requested by the customers. A Ltd. sells the vouchers through its web-application and the vouchers are non-refundable.

A Ltd and the restaurants and hotels jointly determine the prices at which the vouchers will be sold to customers. Under the terms of its contracts with the restaurants, the entity is entitled to 15% of the voucher price when it sells the voucher.

A Ltd. also assists the customers in resolving complaints about the meals/hotels and has a buyer satisfaction programme. However, the restaurant is responsible for fulfilling obligations associated with the voucher, including remedies to a customer for dissatisfaction with the service.

To determine whether the entity is a principal or an agent, the entity identifies the specified good or service to be provided to the customer and assess whether it controls the specified good or service before that good or service is transferred to the customer. A customer obtains a voucher for the restaurant/hotel that it selects. A Ltd. does not engage the restaurants/hotels to provide meals to customers on the entity’s behalf.

Therefore, A Ltd observes that the specified good or service to be provided to the customer is the right to a meal/hotel stay (in the form of a voucher) at a specified restaurant or hotel, which the customer purchases and then can use itself or transfer to another person. The entity also observes that no other goods or services (other than the vouchers) are promised to the customers.

A Ltd. concludes that it does not control the voucher (right to a meal) at any time. In reaching this conclusion, the entity principally considers the following:

(a) The vouchers are created only at the time that they are transferred to the customers and, thus, do not exist before that transfer. Therefore, A Ltd. does not at any time have the ability to direct the use of the vouchers or obtain substantially all of the remaining benefits from the vouchers, before they are transferred to

(b) A Ltd. neither purchases, nor commits itself to purchase, vouchers before they are sold to customers. A Ltd also has no responsibility to accept any returned Therefore, A Ltd. does not have inventory risk with respect to the vouchers.

Thus, A Ltd. concludes that it is an agent with respect to the vouchers. A Ltd. recognises revenue in the net amount of consideration to which the entity will be entitled in exchange for arranging for the restaurants/hotels to provide vouchers to customers for the restaurants’ meals, which is the 15% commission it is entitled to upon the sale of each voucher.

Example: Electronic Airline ticket retailer

Travel agent Ltd. is an entity that sell airlines tickets on its website and mobile application. Negotiates with major airlines to purchase tickets at reduced rates compared with the price of tickets sold directly by the airlines to the public. Travel agent Ltd. agrees to buy a specific number of tickets and must pay for those tickets regardless of whether it is able to resell them. The reduced rate paid by the entity for each ticket purchased is negotiated and agreed in advance.

Travel agent determines the prices at which the airline tickets will be sold to its customers. The entity sells the tickets and collects the consideration from customers when the tickets are purchased.

Travel agent also assists the customers in resolving complaints with the service provided by the airlines. However, each airline is responsible for fulfilling obligations associated with the ticket, including remedies to a customer for dissatisfaction with the service.

To determine whether Travel agent Ltd.’s performance obligation is to provide the specified goods or services itself (i.e., the entity is a principal) or to arrange for those goods or services to be provided by another party (i.e., the entity is an agent), the entity identifies the specified good or service to be provided to the customer and assesses whether it controls that good or service before the good or service is transferred to the customer. Travel agent Ltd. concludes that, with each ticket that it commits itself to purchase from the airline, it obtains control of a right to fly on a specified flight (in the form of a ticket) that the entity then transfers to one of its customers. Consequently, the entity determines that the specified good or service to be provided to its customer is that right (to a seat on a specific flight) that the entity controls. The entity observes that no other goods or services are promised to the customer.

Travel agent Ltd. controls the right to each flight before it transfers that specified right to one of its customers because the entity has the ability to direct the use of that right by deciding whether to use the ticket to fulfil a contract with a customer and, if so, which contract it will fulfil. The entity also has the ability to obtain the remaining benefits from that right by either reselling the ticket or obtaining all of the proceeds from the sale or, alternatively, using the ticket itself.

Travel agent Ltd. controls each specified right (ticket) before it is transferred to the customer. The entity has inventory risk with respect to the ticket because the entity committed itself to obtain the ticket from the airline before obtaining a contract with a customer to purchase the ticket. This is because the entity is obliged to pay the airline for that right regardless of whether it is able to obtain a customer to resell the ticket to or whether it can obtain a favourable price for the ticket. The entity also establishes the price that the customer will pay for the specified ticket.

Thus, Travel agent Ltd. concludes that it is a principal in the transactions with customers. The entity recognises revenue in the gross amount of consideration to which it is entitled in exchange for the tickets transferred to the customers.

Example: Advertising aggregator: principal v/s. agent– Gross Vs. Net presentation A Ltd., is an advertising agency having several advertiser companies in its client list. A Ltd. enters into an agreement with a social media website, WooHoo, to be its sole advertising agent in India. All the advertisers wishing to advertise on WooHoo are required to book advertising space only through A Ltd. and WooHoo cannot be directly approached.

A Ltd. enters into advertising contracts with a client for advertising on WooHoo. The arrangement does not require A Ltd. to provide any production services, i.e., the advertising content is provided by the client. The advertising cost is Rs.10 per click, i.e., each time the users of WooHoo would click on the web link of the advertiser that would appear on the social media site. The consideration payable to A Ltd. is Rs.2 per click. There are no minimum advertising charges.

Monthly payments towards the advertisements (at Rs.12 per the user clicks for the month) made by the advertiser (client) are paid to A Ltd., who, in turn, passes on the payments to WooHoo (at Rs.10 per the user clicks for the month).

A question that arises is whether A Ltd. is an agent (revenue Rs. 2 per click) or principal (revenue of Rs. 12 per click and cost of Rs.10 per click).

In this case, the primary responsibility to provide advertisement services is of WooHoo and not A Ltd. There is no inventory risk. Although A Ltd. has some pricing latitude, it does not appear to be significant. A Ltd. seems to be an advertising aggregator in such an arrangement, rather than an advertisement service provider himself.

Based on the overall, analysis, A Ltd. is acting as an agent under Ind AS 115 and should therefore report revenue of Rs.2 per click.

Example: E-commerce retailer

E.com Ltd., a large internet based retailer, enters into a contract with Fashion, a readymade garment manufacturer, to sell its products through the online platform of E.com. The terms and conditions of the contract include:

-

- E. com will transport the product sold to the end customer;

- E. com does not take possession of the product sold to the customers; however, the customer returns the products back to E.com if they are dissatisfied;

- E. com has the right to return products to Fashion without penalty if they are returned by the customer;

- E. com may earn margin on the products sold, however, and it has flexibility in establishing the sales price of the product;

- E. com may, at its discretion, provide the end-customer its loyalty incentive points, discount points, and other incentives. Fashion does not have any influence on E.com for the incentives that it may wish to give to the end-customers.

- E. com’s latitude on pricing (through incentives provided) indicates that E.com may control the products. However, this factor alone should not be decisive in the principal versus agent assessment. The factors such as, Fashion is responsible for providing the products to the end customer, bears the inventory risk, would also have to be considered in the assessment.

Auctions

56. Some companies host auction sites as part of their on-line activities where users can purchase or sell goods or services. The company ordinarily earns auction revenues through two sources – up-front (listing) fees and transaction-based

57. Listing fees are the up-front fees that the e-commerce company receives at the time a seller registers for a listing to be maintained over a specified period of The purchaser is paying for a service that is delivered over time. It is appropriate that listing fees are recognised over the period of the contract or arrangement, provided there are no significant outstanding vendor obligations to be fulfilled and collection of the related receivable is reasonably certain.

58. Transaction fees are for facilitating the transaction and are usually based on a percentage of the revenue earned by the seller from the sale. Such fees should be recognised as revenue by the company upon completion of the transaction or at the time when no further vendor obligations remain to be performed as per the terms with the

Shipping and handling

59. E-commerce companies selling products on-line often charge customers for shipping and handling activities. Such charges may or may not be a direct reimbursement of the costs incurred by e-commerce companies. Some companies display the charges separately whereas some do

60. In determining accounting treatment, it should be examined whether the products sold on-line are invoiced to the customers at a composite rate including shipping and handling charges or whether shipping and handling charges are recovered separately as an absolute amount or as a percentage of the sale value. In the former case, it may be appropriate to include such charges as a component of sales revenue provided a clear distinction cannot be made between the product value and the shipping and handling charge component. Where such charges are recovered as an absolute amount or as a percentage of sale value separately, these should not be included in sales revenue but should be recorded separately. Thus, such charges should not be included in computing the value of turnover to be disclosed in the statement of profit and loss. Shipping and handling charges should be recognised separately as an income and the actual cost incurred in respect thereof should be recognised as an However, where these charges are clearly a reimbursement by the buyer of the actual cost incurred by the seller, these should be shown as a deduction from the shipping and handling cost in the statement of profit and loss, if the amount involved is material.

61. Under Companies (Indian Accounting Standards) Rules, 2015, the core principle of Ind AS 115 is that “an entity recognizes revenue to depict the transfer of promised goods or services to customers in an amount that reflects the consideration to which the entity expects to be entitled in exchange for those goods or ” However, the transaction price should exclude amounts collected on behalf of third parties (e.g., Goods and Services Tax). Ind AS 115 does not directly provide guidance on whether amounts billed to an entity’s customer such as shipping and handling fees, are collected on behalf of third parties.

62. Entities may determine presentation on the basis of the principal-agent guidance in the standard (i.e., to determine whether the entity is merely a conduit). An entity would record amounts towards shipping and handling, gross unless the entity arranges shipping on behalf of the customer in accordance with the customer’s specifications, in which case, the entity is only responsible for collecting and remitting fees to third parties. An entity would most likely need to assess whether it is acting as a principal or an agent to determine how to present amounts billed and collected on behalf of third

63. When an entity acts as a “pass-through”, amounts would be recognized on a net basis as if the entity was an agent if, for example,

(1) the customer chooses and contracts directly with the shipping/ logistics company, but the entity collects the shipping fee or

(2) goods or services are insured by third parties and the entity is collecting the insurance fee. However, there may be situations in which shipping is offered as customer incentive (e.g., free or discounted shipping terms), which has become more prevalent in e-commerce transactions, or in which entities are responsible for shipping (i.e., shipping is included in the entity’s pricing of a good or service). In such instances, determining whether to recognize amounts of revenue on a gross or net basis may not be very clear.

64. The relevant extracts for Ind AS 115 are as follows:

22 At contract inception, an entity shall assess the goods or services promised in a contract with a customer and shall identify as a performance obligation each promise to transfer to the customer either:

(a) a good or service (or a bundle of goods or services) that is distinct; or

(b) a series of distinct goods or services that are substantially the same and that have the same pattern of transfer to the customer (see paragraph 23).

Ind AS 115 requires an entity to assess the goods or services promised in a contract with a customer in order to identify performance obligations. Therefore, an entity would need to consider:

- Whether shipping and handling activities represent fulfilment activities before the customer obtains control of the goods,

- Whether shipping and handling service would be a distinct performance obligation towards the customer; and

- Whether the entity is the principal for the shipping service or is an agent arranging for the shipping service to be provided to the customer when control of the goods transfers at shipping

65. Following example illustrates the consideration for shipping and handling services.

Example: Shipping service in a FOB contract

An electronics e-tailer enters into a contract to sell flat screen televisions to a customer. The delivery terms are free on board (FOB) shipping point (legal title passes to the retailer when the televisions are handed over to the carrier). A third-party carrier is used to deliver the televisions. The e-tailer has a past business practice of providing replacements to the retailer at no additional cost if the televisions are damaged during transit.

The customer does not have physical possession of the televisions during transit, but has a legal title at shipment and therefore can redirect the televisions to another party. The e-tailer is also precluded from selling the televisions to another customer while in transit.

The customer might conclude that it has two performance obligations: one for fulfilling the order for the televisions and a second for covering the risk of loss during transit based on its past business practice. The e-tailer has not satisfied its performance obligation regarding the risk of loss at the point of shipment.

The consideration from the customer should be allocated to the televisions and to the service that covers the risk of loss. Revenue for the televisions is recognized at the time of shipping when control transfers. Revenue allocated to the risk of loss service is recognized when performance occurs.

Multiple element arrangements

66. A multiple element arrangement generally exists where an e-commerce company agrees to deliver more than one product/ service concurrently and deliver certain additional products/services in future. These additional products/services may include upgrades, enhancements or maintenance services. It is sometimes customary to bundle such products and services for a consolidated

67. For accounting purposes, it is appropriate to ‘unbundle’ the separate elements of the arrangement or contract. For this purpose, company-specific fair values in respect of which objective evidence is available should be used, i.e., what the company would have received had it sold each item/ service separately. Company-specific objective evidence of fair value is determined in respect of transactions with unrelated parties. For example, an e-commerce company may agree to host another company’s website and also provide web maintenance service for a fixed fee of Rs.15 lakh for a term of one year and six months, respectively. If the e-commerce company has evidence that in its recent transactions, it has charged separate fees for web hosting and web maintenance of Rs.12 lakh for one year and Rs.6 lakh for six months, respectively, then revenue in respect of the composite service now being provided should be recognised in the ratio of 2:1, i.e., Rs.10 lakh from web hosting over one year and Rs.5 lakh as revenue from web maintenance services over a period of six months.

68. Unbundling of revenues from multiple element arrangements is not performed where the revenue recognition criteria as well as the periods over which revenues would be recognised are the same for individual elements of the multiple element arrangement.

69. In the absence of availability of sufficient company-specific objective evidence of fair values for the allocation of revenue between various elements, it would be appropriate to defer recognition of the entire revenue from the contract until (a) sufficient company-specific objective evidence comes into existence, or (b) all elements of the arrangement are delivered, whichever is earlier. In the latter case, the composite amount is recognised as revenue on delivery of all elements of Associated costs related to such deferred revenues should also be carried forward until they are capable of being matched against revenues recognised in the financial statements.

70. Ind AS 115 provides a framework for identifying the performance obligations in a contract. When an entity determines that the promised goods or services are distinct, it will need to determine whether it is providing a software licence (as a separate performance obligation from the hosting service) or a service (a licence and hosting services that, together, are a single performance obligation because the two promises are not distinct from one another).

71. In cloud services, most arrangements involving software also include promises for the right to receive services or unspecified upgrades and enhancements (or both) after the licence period begins. Generally, these services include telephone support and correction of errors (bug fixes or debugging), as well as unspecified upgrades or enhancements. These activities are commonly known as post- contract support (PCS). Entities may combine PCS with the software as a single component under Ind AS While other entities may separate PCS as a separate component from the software or even into multiple separate components.

72. PCS is not a unique service contemplated or defined in Ind AS 115. As a result, entities will need to evaluate whether the individual services that comprise what is considered PCS today will be separate performance obligations. For example, a software entity may conclude that the promise to provide unspecified future upgrades and enhancements is a distinct promised good or service in the contract and, therefore, is a separate performance obligation. The entity may also determine that bug fixes and telephone support are provided to ensure that the software is functioning as As a result, those services would be part of the assurance warranty coverage for the software and not a revenue element (such warranties will be accounted for under Ind AS 37 Provisions, Contingent Liabilities and Contingent Assets).

73. However, other entities may conclude that the promise to provide telephone support and bug fixes contains both an assurance-type warranty (non-revenue element) and service-type warranty (revenue element).

Multiple element arrangements- Considerations for cloud Services Company

74. Cloud services include Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) or other products or services. These arrangements also frequently include a licence of the software, for which the customer may (or may not) have the right to take possession. Cloud services may also include other services offerings, such as data migration, business process mapping, in addition to the cloud service These services may be required for a customer to begin using the cloud services in the manner described in the contract.

75. Ind AS 115 requires identification of the performance obligations in a contract. An entity will, therefore, need to determine whether it is providing a software licence, as a separate performance obligation from the hosting service, or a service, a licence and hosting services that, together, represent a single performance obligation because the two promises are not distinct from one

76. An entity may provide a customer with a software licence, but only in conjunction with a hosting service. Also, the customer may not take control of the licence or use the software without the hosting service. In such cases, the customer cannot benefit from the licence on its own and the licence is not separable from the hosting In such a scenario, the licence would have to be combined with the hosting service.

Sales Returns – Right of Return in exchange for cash/goods or services/vouchers

77. E-commerce companies, particularly e-tailers, often provide option of returning the goods for exchange either in cash or goods or services or by way of store credit vouchers which can be used by the customer for subsequent purchases, either with or without a time limit. In such cases, the entity would need to evaluate the appropriate timing of recognising revenue as there is certain level of uncertainty attached as to when and whether the customer would exchange the goods or services and further whether the customer would utilise the vouchers, if any, obtained in exchange of returning the goods or services. While most retailers are able to discern past trends with respect to returns, others may have a varied and disparate experience of ‘sales returns’ and would need to make the best estimates with the available

78. Under Companies (Accounting Standards) Rules, 2006, with regard to uncertainties, paragraph 10 of AS 9, “Revenue Recognition”, states the following:

Revenue from sales or service transactions should be recognised when the requirements as to performance set out in paragraphs 11 and 12 are satisfied, provided that at the time of performance it is not unreasonable to expect ultimate collection. If at the time of raising of any claim it is unreasonable to expect ultimate collection, revenue recognition should be postponed.

Further, with regard to sale of goods, the criteria set out for revenue recognition in paragraph 11 of AS 9, “Revenue Recognition”, are:

In a transaction involving the sale of goods, performance should be regarded as being achieved when the following conditions have been fulfilled:

(i) the seller of goods has transferred to the buyer the property in the goods for a price or all significant risks and rewards of ownership have been transferred to the buyer and the seller retains no effective control of the goods transferred to a degree usually associated with ownership; and

(ii) no significant uncertainty exists regarding the amount of the consideration that will be derived from the sale of the

79. With regard to revenue recognition for service contracts, the criteria is set out in Paragraph 12 of AS 9 states that:-

In a transaction involving the rendering of services, performance should be measured either under the completed service contract method or under the proportionate completion method, whichever relates the revenue to the work accomplished. Such performance should be regarded as being achieved when no significant uncertainty exists regarding the amount of the consideration that will be derived from rendering the service.

5.35 Following Illustration in AS 9 explains the application of AS 9 to commercial situations.

“A. Sale of Goods

……..

2. subject to conditions

………

(c) guaranteed sales i.e. delivery is made giving the buyer an unlimited right of return

Recognition of revenue in such circumstances will depend on the substance of the agreement. In the case of retail sales offering a guarantee of “money back if not completely satisfied” it may be appropriate to recognise the sale but to make a suitable provision for returns based on previous experience. In other cases, the substance of the agreement may amount to a sale on consignment, in which case it should be treated as indicated below.

(d) consignment sales i.e. a delivery is made whereby the recipient undertakes to sell the goods on behalf of the consignor. Revenue should not be recognised until the goods are sold to a third party.”

Thus, where it is assessed that an estimated percentage of sales made could be returned, an adjustment should be made towards such estimated return.

Right of Return in exchange for cash

80. In cases where such right of return is provided, it is appropriate to proceed on the basis that the sales, to the extent of estimate of likely returns, have not been made. Accordingly, sales recognised during the period should be reduced by the estimate of the returns, at the gross amount of sales and a corresponding current asset should be recognised representing the inventory that may be returned. The example below illustrates this

Example: Right of return in exchange of cash

Arc, an electronic retailer, sells shirts with a right to the customers to return the shirts within 60 days of purchase through its website and mobile application. Returns are accepted with proof of purchase and if the shirts are unused and in good condition such that Arc can sell it as new. Historically, 10% of the Arc’s sales are returned by customers and this rate is expected to continue. History has shown that all such returned shirts are resold at full price. The gross margin on sale of shirts is 5%. Customers have option to return shirts by communicating through Arc’s mobile application or website subsequent to which Arc refunds money to the customer against returns, if return is in acceptable condition.

Arc has sold shirts of sale value of Rs. 1000 and the period of return is not expired till the end of the financial year in which sales are made. No returns have been received till the end of the financial year.

There are returns of Rs 80 in the following financial year before the expiry of return period. The accounting entries in this regard are as under.

At the time of initial sale:

| Cash/bank | Dr. | Rs.1000 | Cash received at the time of sale |

| Sales | Cr. | Rs.1000 | Revenue recognised to the full extent |

At the time of Year end

| Sales | Dr. | Rs.100 | 10% of sales based in the past trend of expected returns |

| Provision for expected Right to Returns (Current Liability) | Cr. | Rs.100 | |

| Expected returns from customers (Current asset) | Dr. | Rs.95 | Cost of sales – 95% of sale price – gross margin being 5 % |

| Cost of Sales | Cr | Rs. 95 |

In the following financial year

| Provision for expected ‘right to return’ (Current Liability) | Dr. | Rs.100 | |

| Cash/Bank | Cr | Rs. 80 | Cash paid on right of return exercised by the customer |

| Sales | Cr | Rs. 20 | Balance sales (Rs.100- Rs.80) for which the period of right to return has expired |

| Expected returns from customers (Current asset) | Dr | Rs. 76 | Inventory recognised to the extent of goods returned [(Rs. 80*Rs. 95)/Rs. 100] |

| Cost of sales | Dr. | Rs.19 | Cost of sales recognised to the extent of sales revenue of Rs 20 |

| Expected returns from customers (Current asset) | Cr | Rs. 95 | Adjustment relating to costs reversed |

Right of return against goods or services or vouchers

81. In the case of right of return in exchange of goods or services or vouchers giving the right to the customers to exchange the goods or services sold against other goods/services, the sales against which such right of return is given, should be treated to have been effected and simultaneously provision for expected returns should be made. Provision should be measured as the best estimate of the loss expected to be incurred by the retailer in respect of the estimated returns including any estimated incremental cost that would be necessary to resell the goods expected to be returned.

Example– Return of goods against goods/ services/ vouchers

X is an e-tailer which sells goods through its mobile application/ website. The customers have a right to return the goods within thirty days of purchase. Returns are accepted with proof of purchase and only if they are in good condition such that X can sell it. Customers do not get cash on return but get goods or vouchers which can only be redeemed for goods against returned goods. Estimates show that 10% of all goods sold are returned/exchanged.

At the end of the financial year, the period of right to return has not expired in case of goods sold for Rs. 1000. It is expected that the returns, if any, will be sold at 90% of original sale price. The margin on sale is 20% with regard to such sale of Rs. 1,000. The accounting entries will be as under:

At the time of making the sales:

| Cash/ Bank | Dr. | Rs.1,000 | |

| To Sales | Cr. | Rs.1,000 | |

| At the end of the year: No journal entry |

The reason would be that though 10% of Rs. 1000 worth of goods sold are likely to be returned as per the trend, no loss is expected as the goods are not expected to be sold below cost. (Since expected returns at sale price would be 10% of Rs. 1000 i.e. Rs. 100 and cost would be 80% of Rs. 100 i.e. Rs. 80.)

However, if it is expected that the returned goods will be sold for say 70% of the original sale price (70% of Rs. 100, i.e., Rs. 70), provision for expected loss should be made. The entry will be as under:

| Profit & Loss A/c | Dr. | Rs.10 | |

| To Provision for expected loss on returns | Cr. | Rs.10 |

Since as explained above, the cost is Rs. 80 and expected selling price being 70% of original sale price of Rs. 100 i.e. Rs. 70 and thus expected loss is Rs.10.

Consignment arrangements

82. Many e-tailers sell their products through resellers or consignment agents. Under AS 9, under Companies (Accounting Standards) Rules, 2006, the companies may use sell-through approach for some arrangements with resellers where revenue is not recognized until the product is sold by the distributor to the end customer (that is, the consumer) because the distributor may be able to return the unsold product, rotate older stock, or receive pricing concessions. As a result, the risks and rewards of ownership have not transferred. Some entities sell products using consignment arrangements under which the buyer (a dealer or distributor) takes physical possession of the goods but does not assume all of the risks and rewards.

5.35 Following Illustration in AS 9 explains the application of AS 9 to commercial situations.

“A. Sale of Goods

……..

2. Delivered subject to conditions

………

(c) guaranteed sales i.e. delivery is made giving the buyer an unlimited right of return

Recognition of revenue in such circumstances will depend on the substance of the agreement. In the case of retail sales offering a guarantee of “money back if not completely satisfied” it may be appropriate to recognise the sale but to make a suitable provision for returns based on previous experience. In other cases, the substance of the agreement may amount to a sale on consignment, in which case it should be treated as indicated below.

(d) consignment sales i.e. a delivery is made whereby the recipient undertakes to sell the goods on behalf of the consignor. Revenue should not be recognised until the goods are sold to a third party.”

Therefore, under AS 9, generally, revenue should not be recognised until the product is sold to the end- customer because they do not meet all of the criteria in the risks and rewards model in AS 9 to recognise revenue on delivery to the reseller.

83. Under Ind AS 115, entities must first evaluate when control of the product transfers to the In this respect, they need to assess whether their contracts with resellers are consignment arrangements. In a consignment arrangement, control generally does not transfer (and, thus, revenue is not recognised) until the reseller sells the product to an end-customer.

84. Ind AS 115 provides the following guidance in case of consignment sales:

B77 When an entity delivers a product to another party (such as a dealer or a distributor) for sale to end customers, the entity shall evaluate whether that other party has obtained control of the product at that point in time. A product that has been delivered to another party may be held in a consignment arrangement if that other party has not obtained control of the product. Accordingly, an entity shall not recognise revenue upon delivery of a product to another party if the delivered product is held on consignment.

B78 Indicators that an arrangement is a consignment arrangement include, but are not limited to, the following:

(a) the product is controlled by the entity until a specified event occurs, such as the sale of the product to a customer of the dealer or until a specified period expires;

(b) the entity is able to require the return of the product or transfer the product to a third party (such as another dealer); and

(c) the dealer does not have an unconditional obligation to pay for the product (although it might be required to pay a deposit).

85. Revenue should be recognized when a good or service is transferred to the customer. An entity transfers a good or service when the customer obtains control of that good or service. A customer obtains control of a good or service if it has the ability to direct the use of and receive the benefit from the good or

86. Indicators that the customer has obtained control of the good or service include:

– The entity has a present right to payment for the

– The customer has legal title to the

– The entity transferred physical possession of the

– The customer has the significant risk and rewards of

– The customer has accepted the

87. A product is held on consignment if the buyer has physical possession of a good but has not obtained control. An entity should not recognize revenue for products held on consignment.

Indicators that there is a consignment arrangement include:

– The product is controlled by the seller until a specified event, such as a sale to an end

– The entity is able to require the return or transfer of the

– The dealer does not have an unconditional obligation to pay for the